- Share via

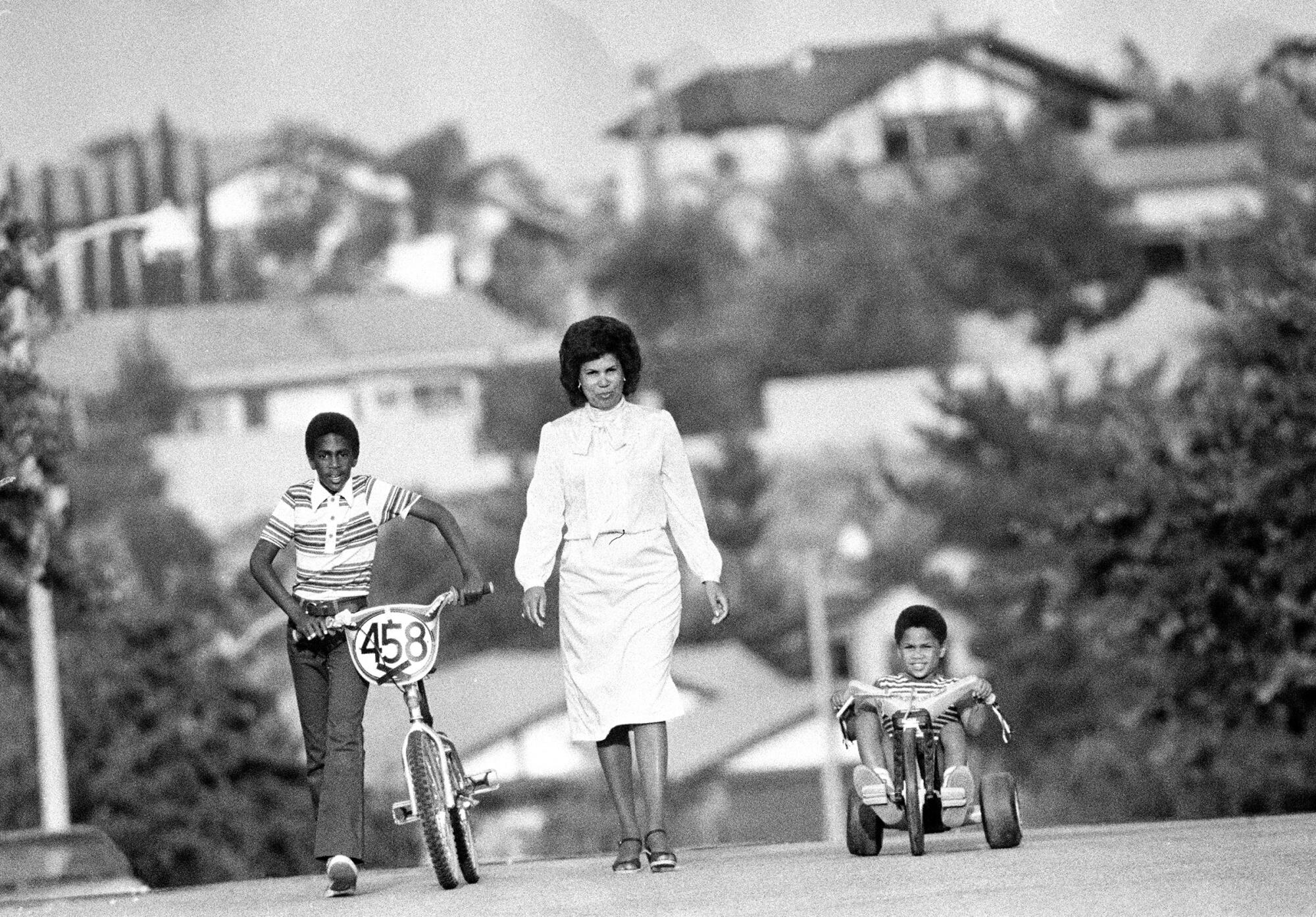

More than four decades ago, groups of Black and Latino journalists embarked on an endeavor to tell stories about their communities that the Los Angeles Times was failing to showcase. Little did they know that 40 years later the reporting they did and the stories they told would still have a legacy of perseverance.

Two projects that were the first of their kind were published in The Times in consecutive years. In 1982, “Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity” aimed to tell the stories of Black Angelenos. The following year the series on Southern California’s Latino community was published, and would go on to win the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for Public Service. These projects not only set the precedent for diversity initiatives at The Times but they also helped change long-standing misconceptions of L.A.‘s communities of color.

Until 2020, the Latinos series was not available online until a group of journalists at The Times saw the foundational significance the series had. They worked to upload the articles, photographs and other documents to make the series accessible to future generations.

Although change was not immediate after the publication of these projects, they were catalysts for conversations and have acted as role models for advancements like “Behold,” which shares stories, portraits and videos inspired by Black joy, and De Los, which aims at covering topics on culture and identity for U.S. Latinos. It was heroic of those journalists 40 years ago who demanded more and wanted to share stories that deserved to be told.

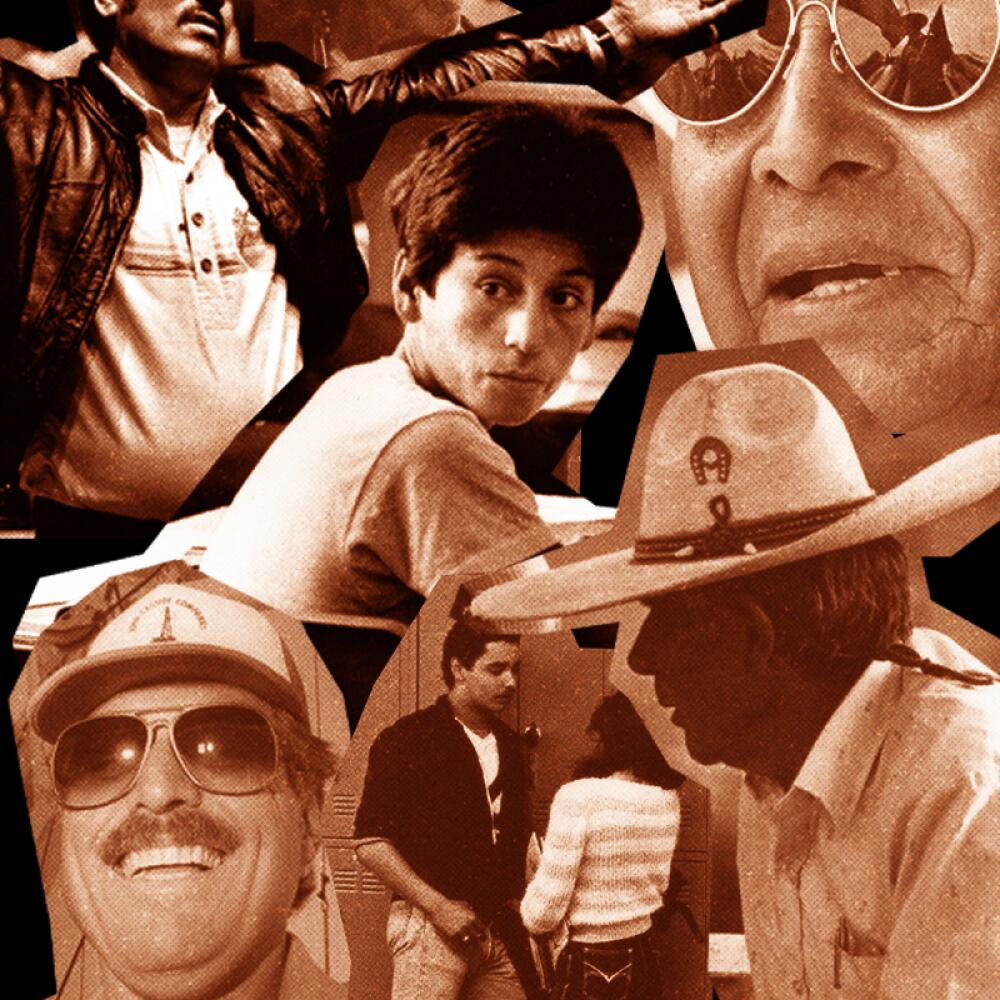

In the summer of 1981, The Times, a predominantly white newsroom, published a jarring piece on its front page titled “Marauders From Inner City Prey on L.A.’s Suburbs.” The piece was about the rise of crime across the city and used words like “savagery” to describe the crimes that were being committed. The article stated the majority of the robbers, burglars and thieves were coming from “ghettos and barrios.”

A group of Black journalists were tired of the negative tone constantly being attributed to Black Angelenos, and they wanted to change the narrative. Their goal was to share authentic stories of the positive things people were doing in their communities, but also use a magnifying glass to expose the harsh reality that many were facing.

Sandy Banks began at The Times in 1979 and was a member of the group of Black journalists who reported on the project. She said that the small but strong group of other Black journalists saw this project as an opportunity to respond to the “Marauders” piece. The team did not have any Black editors; The Times did not promote or hire Black journalists to those positions.

“I was struck by how Neanderthal the thinking was and how the newspaper would use terms like ‘savages,’ ‘animals’ and ‘predators’ to describe us and no one was bothered by that,” Banks said.

In almost every area of life, Blacks argue persuasively that the white-owned media distort black life — when they aren’t neglecting it altogether.

Banks, who is originally from Cleveland, had moved to the San Fernando Valley with her husband. She said the team working on the project all taught each other something and learned from one another.

“When we began talking about having a Black project and we were all going to be involved, it was a way to do the kind of journalism that we thought the paper needed,” Banks said. “But it was also a way for us to connect and to feel a part of something bigger.”

Frank Sotomayor, who joined The Times in the 1970s, served as one of the editors for the 27-part series on Latinos. He was a part of the initial conversations alongside George Ramos and Frank Del Olmo. They pitched the idea and assembled their team of Times reporters.

“On January 4, 1983, the team reported for work, ready to take on our assignment of a lifetime. Along with energy and enthusiasm, a few of us felt a bit of apprehension. Here we were, ready to take on what was surely one of the biggest reporting projects in the 101-year history of the L.A. Times,” Sotomayor wrote in his book “The Pulitzer Long Shot.”

Nancy Rivera Brooks was 25 when she was asked to join the Latino group of journalists. Rivera Brooks recalled the early thought process that went into the creation of the series and says they looked to the courage of their Black colleagues.

“We batted around story ideas and what we should write about and how we can make this different and build on the work of our colleagues in the series about Black Americans,” Rivera Brooks said. “There was a lot of pressure from outside of the newsroom and the jokes that we would hear.”

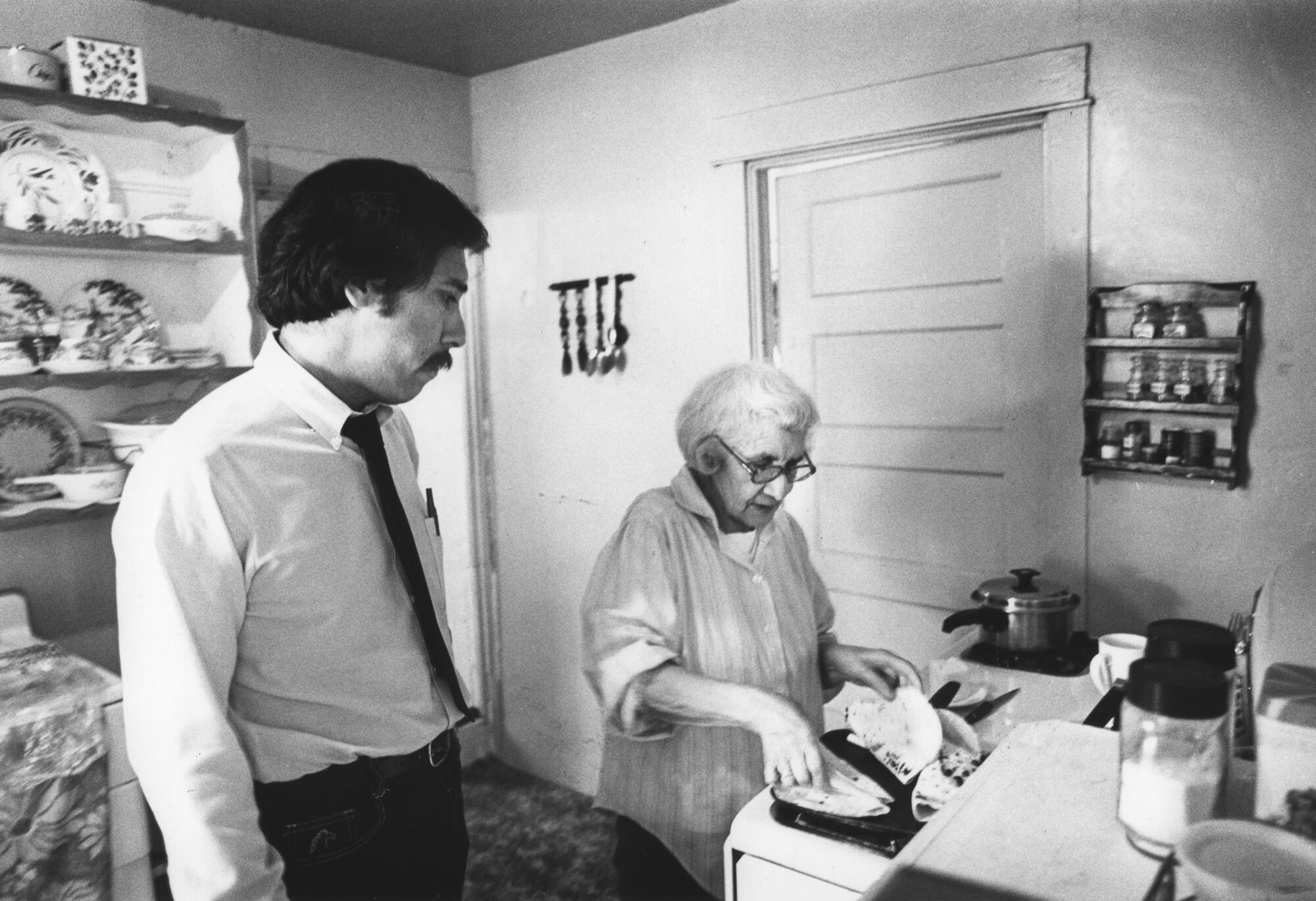

Generations of a family recall their memories of coming to California and the challenges they faced

Rivera Brooks said that a number of white colleagues in the newsroom doubted their ability to produce a good series. She said that the lack of confidence was rooted in “white privilege.” Not only did she feel pressure from within The Times but she also felt pressure from herself. She wanted to make sure she wrote the best stories that she could.

Looking back at her work on the series, Rivera Brooks said the series helped her feel more connected to who she was. As a Mexican Irish woman, Rivera Brooks said she often struggled with her identity when she heard comments like “you don’t look Latina.”

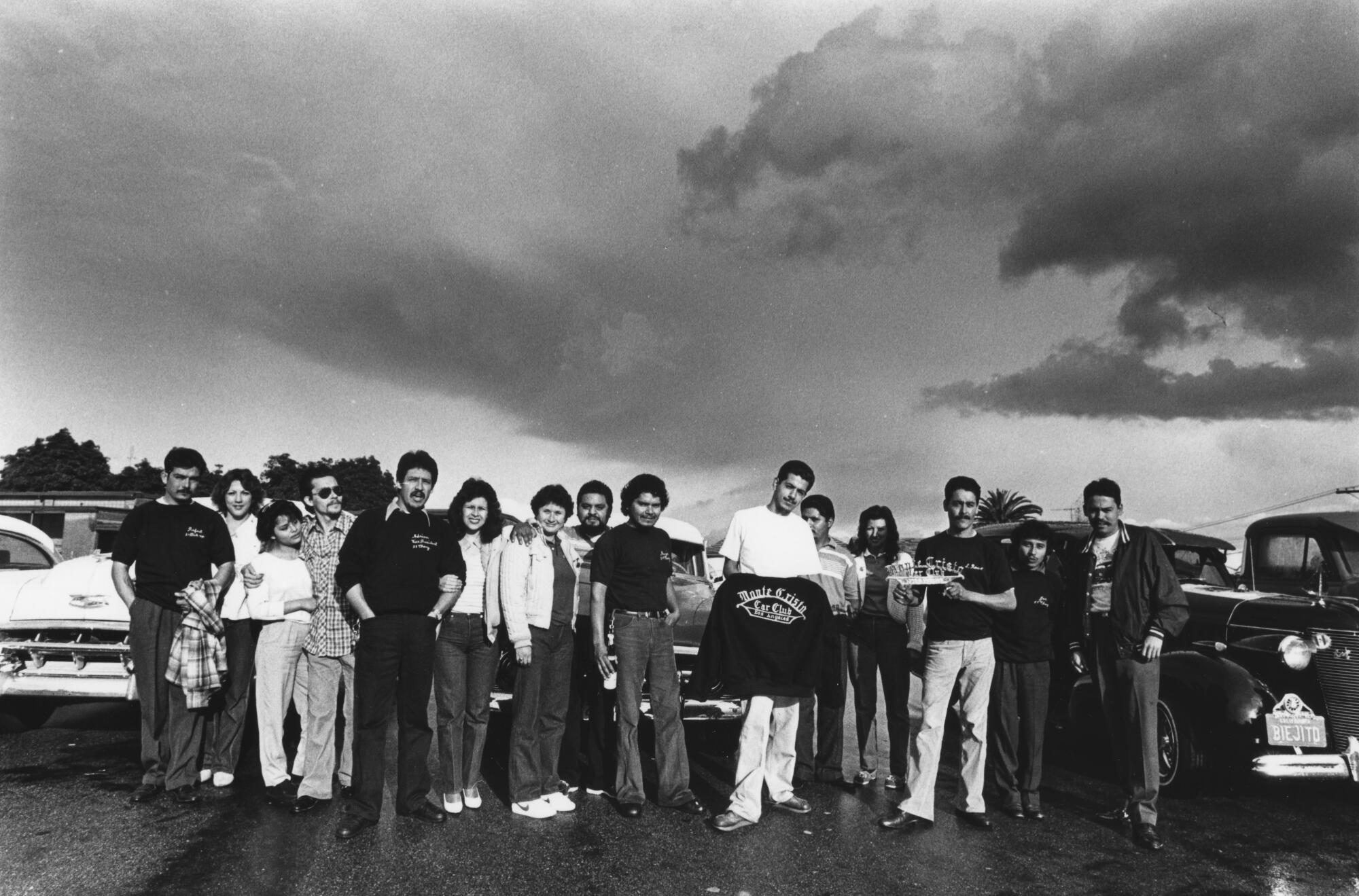

The Latino series covered a variety of topics like Latino-owned businesses, the world of Latinas, education, the Chicano movement, activism and an extensive profile on Boyle Heights written by Louis Sahagun.

Sahagun began working at The Times as a floor sweeper in 1973 before he got his start in reporting. He had no prior experience in journalism and went from sweeping floors to become a copy messenger and eventually to writing book reviews. He felt an “enormous pressure” to set the record straight about Latinos in L.A.

“It was an enormous pride when we finally finished the thing. It is a series of documents, some well-written, informative pieces, not just for Latinos, but for everyone across the country to see this place in a realistic way,” Sahagun said.

Richard Veloz and Irene Calvillo for 10 years have tried to raise money and community interest along Whittier Boulevard in Boyle Heights to help gang members return to school or find jobs.

He recalled how the team would meet in restaurants, crammed living rooms and conference rooms to share ideas and plan out the series. He said there was an incident when a few members met at the Redwood saloon and restaurant that was only a few blocks away from The Times’ downtown office. They sat and discussed the series in a booth when a white journalist sitting nearby overheard their conversation and said, “So, when can we expect to see this debacle?”

Both projects were met with hostility from the beginning, but the journalists prevailed not only professionally in their reporting but also personally as they grew. Rivera Brooks, Banks and Sahagun said they learned so much about themselves through the projects. Both groups of journalists were recognized with awards and accolades, and in 1984 the Latinos series won one of journalism’s highest honors, the Pulitzer Prize.

“The biggest thing that I took away from it, and it has been the North Star of my career since then, is to find my voice and to use it,” Banks said. “I believe specifically at The Times, we set up a culture that allowed us to have identities.”

Sotomayor wrote that then-editor Bill Thomas did not think that the series was worthy of a Pulitzer nomination. Sotomayor and the other editors met with Thomas multiple times to explain why, and how the hard work and bravery of the group of Latino journalists deserved to be recognized. Thomas eventually allowed the series to be submitted and even stood on stage to receive the award at the ceremony.

Migrant pickers talk about their work in the fields.

Those same topics and stories from decades ago continue to resonate with those same communities today. Rivera Brooks said that all you have to do is change the date on some of those stories and they still stand true currently.

Black and Latino communities around L.A., and the country, continue to face inequality and underrepresentation in the media. Sahagun said it is not always easy but continuing to take advantage of those moments where you can change history and doing your best work are ways to help advance the fight.

Read the series in full:

The Times’ 1982 series ‘Black L.A.: Looking at Diversity’

The Times’ 1983 Pulitzer Prize-winning series on Southern California’s Latino communities

More to Read

The Latinx experience chronicled

Get the Latinx Files newsletter for stories that capture the multitudes within our communities.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.