Inside the world of Latinas

- Share via

For many Latinas, there is a double burden of racism and sexism. Five women talk about their experiences, their family relationships, their lives and their concerns:

Julia Luna Mount

Julia Luna Mount might have been an ordinary woman, but she never forgot what Miss Murphy told her 50 years ago.

“Look at your hand, dear,” Miss Murphy said when Julia showed up for her typing class. “See how dark it is? Who’s going to hire you?” Julia, a frightened girl of 12, protested and took the class anyway. The only brown child in a sea of white faces, she had taken her first stand in a lifelong series of causes.

At 14, she went on strike at the cannery where she worked at night and became a founding member of a cannery workers union. Mount picketed the Welfare Department when it doled out beans to Mexicanos while others got milk, meat and vegetables.

Later she protested U.S. involvement in Korea and Vietnam. She lobbied for bilingual education and ran for the school board and the state Senate.

Then, her father, step-grandfather and brother died of cancer. Julia and her sister Celia each lost a breast to cancer. Julia believes there is a link between her family’s cancers and atmospheric radioactivity resulting from nuclear weapons testing in Nevada.

In 1979, she formed the East Los Angeles Alliance for Survival, an anti-nuclear group.

Julia Luna Mount, 61, mother of four, grandmother of 10, now is protesting the end of the world.

::

Miss Murphy had the nerve. What do you answer this person?

I had another teacher, my Uncle Chuy. He was a terrific guy, a self-taught guy. He used to talk to me about the struggles of people, about world events.

Chuy would invite me to meetings: “Maybe you’d like to come and learn about what’s happening and why people are having so much trouble with their gas, their light, with their closing of this or that.”

An organization of the unemployed was formed. The Workers Alliance of America. We were very active. Whenever they turned anybody’s gas off, we’d go turn it on. Whenever they evicted anybody and threw all the furniture out, we’d put it back in the house. When they shut the water off, we’d open it. When they turned off the lights, we put them back on.

‘We’re going to have to someday go to the polls and do away with something that’s killing us. But we’re not going to win unless people are educated.’

— Julia Luna Mount

ln 1944, Mount, a county typist, helped organize the county employees union. Later she ran for public office.

Gloria Molina got elected (to the Assembly in 1982), but not me in 1967. Women weren’t running for office then, especially Mexicanas. You crazy or something? Ha! But I thought, “Even if I’m not elected I will say the things that I think have to be said.”

I ran for the school board because I cared, because 50% of our (Latino) young kids were dropping out of high school and junior high where I went—where I had trouble because I would speak Spanish during lunch.

They would give me half an hour of detention. I accumulated 532 hours of detention for speaking Spanish. I never did take them. They kept threatening me, but I knew I was right because during your free time you were supposed to do what you wanted to. Later on, of course, I went to Sacramento to lobby for bilingual education and we got the first grant (for Los Angeles).

Now Mount campaigns against nuclear war.

I want to emphasize the fact that as minorities, as Mexicanos, we lack housing, medical attention, good schools, jobs. We lack for everything that you can think of. For us, it’s always been an economic struggle, but right now it’s a struggle for survival.

In the summer of 1983, The Times published a series on Southern California’s Latino community.

These two big powers (the United States and the Soviet Union) have the capability of destroying themselves I don’t know how many times over.

The most important thing is, are we going to be here two years from now and what’s it going to be like?

It’s an ugly period and it’s a sadder period for the children that are coming. Some people don’t understand these things, but some of us wonder if there will be any future generations. Sometimes, it’s really upsetting enough that I can’t sleep at night.

She says she faces special problems organizing in predominantly Latino East Los Angeles.

Nuclear energy is a very difficult subject to get into with people in our area. Mexicanos are less informed for many reasons. The subject is never covered in the Spanish-language media. But, first of all, they’re so busy scratching for something to eat and pay the bills, they don’t have time to think about anything else.

I’ve talked to a lot of people and the majority of Mexicanos tell me, “Oh, that’s the white man’s problem.” Well, I’ll grant you that it was the white man that made the problem. He is solely responsible.

But now, it is an international problem, because if the whole world goes up in smoke or into something uglier than that, it’s just going to be too bad for all of us.

When Truman said we did a beautiful thing when we dropped those bombs in Japan-Nagasaki, Hiroshima, 1945-l cried all day because I was pregnant.

That maniac. I was going to have my first son and I kept thinking, “What kind of a world are we bringing children into?” I worried the rest of that pregnancy because they had done all these tests.

I can still see that we’re going to have to someday go to the polls and do away with something that’s killing us. But we’re not going to win unless people are educated.

I made it my business to do some studying, to learn and to read. Everything I could get a hold of I’d read and I still do today. . And no way, no way am I ever going to be convinced that nuclear energy is safe.

But Mount has not given up and is trying to educate others.

Talking to different groups is my way of looking out for our future generations, to leave them a world as we know it and not leave them completely hopeless.

My son tells me, “It’s already programmed that the world’s going to end.” It bothers me because I keep telling him, ‘What if we make it?’

He laughs, “No, Ma. We’re all going to die.” It makes me so sad.

But some of us are thinking ahead. Maybe we can stop annihilation by urging those people in government positions to reflect and see where we’re headed.

The whole process of this nuclear menace should become a women’s problem War affects us more than anything else because we’re the ones who lose our future husbands, husbands and children.

If women controlled the world, we would not have wars because we are the givers of life.

Nancy Gutierrez

In 1959, Pacific Telephone Co. hired 16-year-old Nancy Gutierrez as a switchboard operator. She learned quickly. At 19, Gutierrez was a business office supervisor; by the early 70s, she was supervising the foremen in charge of installation and repair crews. It was not a traditional job for a woman, but Gutierrez sought the assignment because she believed it would enhance her career prospects.

Today Gutierrez,41, is back on the “people” side of the company as district manager for corporate management recruitment. She shuttles between her Los Angeles and San Francisco offices, directing the search for management talent, especially minorities and women.

One of the few Latinas in corporate management, Gutierrez made it without a college degree; higher education was reserved for the men in the family.

But to enter the business world now, she emphasizes, a degree is vital.

::

Somebody says all the time to me, “What is it that you had that made a difference?” And, you know, it’s really kind of hard to reflect back on that.

I think my fork in the road was looking around and realizing that one has to take risks . . . . I think my ability to be very straightforward about things was perceived as a strength. Being straightforward is my personality, for one thing, but it’s also a very nice and common-denominator trait for Hispanic women. I think we are very honest, and that can be detrimental to us. But in some cases it can be seen as a strength.

I think tremendous strides have been made between the time I started and now. It isn’t a rarity to see women at parity at meetings . . but women have not really made it in corporate America. We talk about it but you don’t see very many women CEOs (chief executive officers) unless they’re entrepreneurs. And you don’t really see very many women in policy-making positions. . .

The biggest frustration for women moving up in the corporate arena is that you have to have a tremendous strength-to be very thick-skinned, as they say-and have a lot of confidence or self -esteem.

Hispanic women need a support system to nurture those two variables. And a lot of them don’t have that.

I had two very strong role models in my grandmother and my mother. But I happen to be a Hispanic from New Mexico-third, fourth, fifth generation-versus a lot of the Latinas that are here in California who are not. They’re first generation.

They have no support system. . .

You do feel isolated at times and very frustrated. I happen to have been fortunate that I have a very close family, so a lot of times I could bounce many of these things off my brothers.

‘After a while you aren’t perceived as a Hispanic woman; you’re perceived as a corporate manager.’

— Nancy Gutierrez

When I went on the technical side (at Pacific Telephone), I was very much inhibited by these burly guys who had been in the environment for 30 years and had worked their way up through the technical arena. And you had to feel for them, that here they were reporting to a woman, and a minority at that, who didn’t even know that much, in their viewpoint, of what the makings of the system were . . . I felt myself very much isolated and very much frustrated about “Gosh, maybe I’m just not in the right place.” I started to forget that I was the boss and I started letting the gender take over my mind.

I remember discussing this with my brother, who happened to be a foreman for Mountain Bell. And, in perspective, had I been in Mountain Bell, I would have been his boss.

He said, “Look. Put your shoes on their feet. Some of those guys have worked, and worked really hard, and it’s not you as a personality. It’s just a situation where they’re not any further (up in the company) and they just feel a lot of frustration.”

Latinas climbing the corporate ladder encounter problems that others do not, she believes.

I think that, No. 1, we have a tendency sometimes to maybe not go as far as our potential would take us because we have very strong family ties . . . We’re, first of all, a very family-oriented people, a very loyal people to that commitment. We also fight the issues of sexism within our own race, within our own heritage . . . Those are extra pressures that the Hispanic woman has to face.

There’s something else. We have to have an ability to be multi-personalities, because we have to come in and assimilate into the culture of the corporation, into the culture of the peer group, which is predominantly non-minority.

I’m not saying this in any kind of a hypocritical way, but I’m saying that we have to understand it. Because, remember, the management is predominantly male white; 95% of the decision makers in corporate America are male white. They’re more comfortable around white females. Their mother is a white female, their sisters are white females. They understand that female more than the minority female. So the minority female has to adjust into that kind of an environment.

Latino men who succeed in the corporate world often resent Latinas who are trying to do the same, a reflection of sexism in the Latino culture, she says.

I think these men have a tendency to perceive that they are the only representation of (Latinos in) corporate America, that women just have not really come of age for that.

Not only do they have to be threatened by the Anglo male and the women’s movement, but now the Hispana is starting to take up the baton and is starting to twirl it, and she’s not stopping when they say, “Stop.” And we’re starting to be a little bit more assertive in saying we want representation, we want recognition.

When an organization, a Hispanic organization, predominantly male-run, doesn’t have parity representation on their boards, we’re starting to say to them, “Hey, tell me about this.”

But she is confident Latinas can succeed.

I’m very committed to encouraging young Hispanic women to expand their horizons. They can do whatever they want to do. They can be whatever they want to . . Sexism and racism are well and alive in corporate America. I think it’s being controlled. And it’s well and alive in our own heritage, in our own community. But what we have to do is learn to not dwell on it. Learn it’s there, don’t be naive, be realists, and go forward . . .

We’re just a young people. We haven’t had a lot of experience in corporate America. As Latinas, we’re just starting to experience positions where you can make judgment calls and you’re the boss. You make the decisions. You run the organization. And, you know, after a while you aren’t perceived as a Hispanic woman, you’re perceived as a very good corporate manager. And isn’t that what we’re all trying to achieve?

The Status of Latinas, 1983

Population: Of 7,328,842 Latinas nationwide, nearly 4.3 million are of Mexican descent with a median age of 22. ln California, there are 2.24 million Latinas.

Job status: A few women are breaking new ground as corporate executives, university administrators or other professionals. But most Latinas remain in low-paying jobs as typists or factory workers.

More Latinas joined the labor force by economic necessity or choice—from 44.6% in 1976 to 49.9% in 1983. But in 1980, according to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 51% of them were unemployed or underemployed.

Latinas earn 49 cents to every dollar a white male gets. (On that same basis, white women get 58 cents and black women 54 cents.)

Education: On the average, Latinas have completed only 8.8 years of school, compared to 12.4 for the general population.

Single parents: Women head about 20% of all Latino families. The number of poor Latinas in this category doubled between 1972 and 1981, from about 800,000 to 1.6 million. Of those households headed by a Latina and with children under 18, 67% were under the poverty level.

Divorce: The divorce rate for Latinas rose from 81 to 146 divorced persons per 1,000 in active marriages between 1970 and 1981. (The comparable 1981 rate was 1 18 for white women and 289 for black women.)

Activism: Latinas have a history of strength and activism, said Adelaida Del Castillo of UCLA, including a record of strikes spanning almost every arena of their labor, from fields to factories. ln the last decade, Latinas have taken a more active role in education as parent council members, teachers’ aides and school officials. Latinas are also active on a variety of fronts, through unions, networks in higher education, law, business, social agencies and community groups.

Future: Maria Rodriguez, an attorney for the Mexican-American Legal Defense and Educational Fund, said: “l’m very optimistic about the future because I continue to meet outstanding Latinas with some real leadership ability and concern about Latinas as women. Latinas have unique problems that we need to address if we want to improve conditions for all Latinos in this country.”

Cristina Ramirez

Cristina Ramirez is a 29-year-old organizer for the International Ladies Garment Workers Union in Los Angeles, wife of a Chicano lawyer and the mother of one child.

She draws strength from her mother, who raised eight children on her own in Ecuador, and her youthful days in a union hall where she heard Ecuadorean oil workers talk about their aspirations for a better life.

Today, as a union organizer in the garment industry, she sees firsthand the new roles that Latinas take on as they enter the work force. For Latinas who come to this country to escape economic and political oppression, the garment industry often gives them their first job, but in a world of work dominated by men.

To Ramirez this explains the exploitation they suffer-sexual harassment, low wages and forced overtime. Still, she believes that the future belongs to her union and the Latinas who continue to build it.

::

I was born in Guayaquil, Ecuador, and lived there till I was 16. I came to this country in 1971 and finished high school here. After that I started working in this garment factory as a (thread) trimmer. My older sister and my mother used to work there, too.

When I was working as a trimmer, I saw a lot, I suffered a lot. The first nine months that I was living in this country I cried every day. Because when I went to work, the guy that used to give the work out, he used to tell me that if I was good to him he would give me the best work. Like if I’d go out with him and stuff like that. It was sexual harassment and I was only 18 years old.

It was real common. Supervisors would get the men together, all the (pattern) cutters, like when they were going to hire a new girl. The men would give the OK to the supervisor if they liked her or not.

If the girl who went to apply was good-looking, sure. If it was an old lady, a mature lady, they didn’t give her the job.

(And) the way you work here... only a half-hour for lunch. Eating on top of your (trimming) machine. It was hard doing the same thing everyday, cutting threads, the same routine. You didn’t have time to talk to anybody, not even a friend. I think it was $1.55 an hour then. I was treated as an animal.

I would like to erase (those memories). But I see a lot of people still go through the same thing.

In 1975, Ramirez set out to organize Latinas working in a medical supplies plant. At first, she worked undercover, as an employee at the plant.

They put me in shipping, and it was like a concentration camp. I haven’t been in a concentration camp, but I think this will be the closest I can get.

‘The first time we leafleted, you should have seen the people.... They didn’t complain about money; they complained about the treatment.’

— Cristina Ramirez

So I go back and work all day on my feet in shipping, filling orders. You had to produce so much, a quota. If you didn’t do it, you got a warning. I didn’t get any; I was a good worker.

There were three men working and three women. The men were making 5 cents more. So I went to the office and I asked them how come they’re making 5 cents more and I’m producing the same.

The minute I opened my mouth, there was a problem. They called the vice president, the president. I was there by myself. They were asking me, “Are you sure you do the same thing?” I said, “Yes. Why are you paying them more? If you keep doing this, I’m going to file suit against you, that’s discrimination.”

One guy was going to threaten me. “Get rid of her.” But the other guy was smarter. He told him, “Shut up, she might file charges.” So the other guy said, “Tell her she’s going to do the same work the men are doing; if she does that, we’ll give her 5 cents more.”

I said, “I’m already doing that.”

After that they really harassed me, and they didn’t give me the 5 cents. They told me to go pick up heavy stuff. I had to climb the ladder. They put all the pressure on me, watching every single thing I was doing.

So after that I decided to quit and started organizing from the outside.

Ultimately, the workers joined the union and struck for nine months to win a contract. Ramirez believes the turning point came when a new supervisor was hired a few days after she quit.

People had been there so many years, and nobody had been able to organize them. But they changed supervisors. This lady, she wanted more production, faster, faster... She called the workers bestias (beasts), stupids. She would go around the machines: “Can’t you work faster? Are you stupid? You have to produce more!”

People started reacting to that because they were not used to that treatment.

As soon as the supervisor started pushing them around, they called us. The first time we leafleted, you should (have) seen the reaction of the people trying to get the cards to sign. They needed a union to stop that woman, because they didn’t complain about money, they complained about the treatment.

Cristina says the workers she organized often emerged from the experience more conscious of their rights as women, more willing to confront sexism at home.

After one union campaign, one woman said, “Thank you, because you made me see a lot of things I didn’t see before.”

“Why? How?” I said. “You’re still the same person, you’re still working in the same shop.”

“Now, I don’t keep my mouth shut for anybody. I’m not afraid of the police, of anybody. If they (the police or Immigration and Naturalization Service) stop me for something, I don’t know why, but it’s something that you taught me how to do, to respond to anything, to argue about anything.

“I’m even divorced now. And I thank you for that.”

One time she had brought her husband over to my house. It was my husband, the woman and her husband having dinner. And there was this big discussion of (the woman’s responsibility to take part in union activities). Her husband was stopping her from participating.

(I told him that) “something is wrong about this, because she has to participate, she’s one of the strongest leaders. If she doesn’t participate, everybody is going to get discouraged and nobody is going to show up on the picket line.”

(He answered) “Well, yeah, but she has this responsibility (at home), plus I’m taking care of the kids more, and I have to go and play soccer.” He couldn’t play soccer because she wasn’t in the house anymore. They had been married 11 years, they had two kids. They were from Mexico.

But they had all the problems, family problems for years. I think he was going out with other women. But when she started developing, she started fighting, demanding more in every part of her life. When her husband went out with another woman again, she said, “This is it. I’m moving or you go out.”

He begged her, you know. He even went to me to see if I could talk to her, that he was going to leave that woman and all that. But she never went back to him. She’s taking English classes at the union now. She’s really active in the union, she is still raising her kids. She’s about 40, she wants to do something with her life.

Latinas, observes Ramirez, must remember they have the same rights as men.

The woman has to wake up in the morning, feed the kids, take them to the baby sitter, go to work, come back, pick up the kids, cook, serve the food, put the kids to bed, wash dishes, clean the house. And what does the man do? Wake up, go to work, come

back, eat, watch TV, go to bed.

But I think that I have the same rights as a man. I’m not competing with men or women. I just think we are all the same, with the same rights. But sometimes we are faced with certain men who think we are not the same. So we have to educate those men. It takes a lot of guts. But you have to be ready to say, “I’m going to put a stop to this.”

Catalina (Katie) Castillo Fierro

Catalina (Katie) Castillo Fierro, 59, the mother of five, is a housewife in the northern Orange County community of La Palma.

She was born in Long Beach, where her parents settled after leaving Mexico in 1915 to escape the revolution there. In January, 1932, her family was among thousands of Mexican immigrants placed on trains in Los Angeles and deported to Mexico. Her parents had not become naturalized citizens; Katie and her brothers were among those U.S. citizens deported.

Scenes from that Depression-era backlash against Mexican immigrants are still in her mind: the humble basket of Christmas toys she clung to throughout the trip; a young woman who raced from window to window inside the train as she tried not to lose sight of her boyfriend outside.

In Mexico, her father was a farmer, successful for a time, then slain by wealthy land owners in a dispute over water rights, she said.

Katie helped her mother raise her sister and six brothers, endured ridicule in Mexican schools because she was an Americana, and then returned to California-and renewed discrimination-just as World War II began.

Yet, after all this, Katie exhibits no bitterness. Instead, she speaks of the strong family bonds that helped her endure.

::

We learned a lot (in Mexico). We learned other customs, other ways of thinking, how to work in the yard and in the home.

When we came back (to California in 1941), we didn’t know how to speak a single word of English.

We lasted a few months in Westminster. The little ones went to a school where only Mexicanos went.

The first time I went to the movies in Santa Ana, I went with my friend. After we grabbed our tickets, we went to take a seat. Then my friend calls me. “No, no, no-come over here.” “Well, why?” I asked.

Katie Castillo Fierro with husband Pete, son Richard and daughter Magdalena

Times photo by Monica Almeida

‘l never felt I had to be more than a housewife. l’m not a professional, but I learned a lot of things in my life. l’ve worked. But when any member of the family gets sick, l quit.’

— Katie Castillo Fierro

She tells me, they don’t let raza (our people) come in here. “Do we have to go to the balcony,” I asked her.

“Yes, come over here.”

“No. I’ve never liked to sit in the balcony. If they don’t let me come in here, then I won’t leave them my money.”

They gave us back our money and we went. My friend went along laughing, “We’re already used to it.”

“Well, it’s your fault ‘cause you let them treat you like that.”

So then, from the very beginning, I’ve always felt myself equal. I felt like a person anywhere. And I still feel that way.

In that barrio, they used to call it La Garra (The Rag), there was nothing but Mexicans living there, and the houses weren’t that good . . no sidewalks, no nothing. Even though we had just come from Mexico, it wasn’t what we wanted. I wanted to live in a place where you could learn something, not go backwards.

So then we got out of there real quick. We went to Long Beach.

During and after the war she worked at Douglas Aircraft. Then in 1949 she met Pete Fierro, who was just out of the service. They married in 1950; their first child, Peter Jr., was born a year later. They moved from Long Beach to the barrio in Wilmington and Pete began a 30-year career at the General Motors plant in South Gate.

When I got married, I knew I was going to have children. I said, “I’m not going to work,” because I worked to help my mother. I didn’t have the luxury of not working all those years. I had to have the dinner and the house ready. So when I got married, I said I’m going to be with my children. I wanted to have six children-three boys and three girls.

In the years that followed, Katie gave birth to three boys and one girl. One son was asthmatic and the daughter was born with club feet. Then, at 43, she gave birth to her fourth son, Richard.

He surprised us (but) I was very happy. But I was hoping I would have another little girl. We have our religious convictions. You’re not responsible for a life. It’s like the ones that I lost. I lost three; the reason, I don’t know. I have always thought that if y’ou’re going to have a child, it’s because God’s given it to you. You accept it. It’s a blessing.

I have high blood pressure, so I have to be on a strict diet. When (her son) Robert was born, I learned I was a diabetic. But it’s no problem. I mean, I have this health problem, fine. I’m the only one, so I don’t think it’s fair to deprive them of all the goodies.

In 1953, Katie and Pete left Wilmington and bought a tract home in Lakewood.

To save that money was a struggle. It was $400 down. We gave $100, then we raised $300 more. We were criticized: “Those are people with money, what you doing over there?” Our own relatives, they couldn’t understand. We didn’t say anything and we bought our house anyway.

We were very broke. When you don’t have too much, you have to learn how to do a lot of things. I used to make my daughter’s clothes, my clothes. Hand-me-downs, I used to redo them, put a pretty scarf on an old dress, stuff like that. As long as I had a good pair of shoes and stockings, you can make even a simple, fresh cotton dress look pretty.

An episode in Lakewood was troubling.

One day a little (Anglo) boy came to visit us. “You shouldn’t be living here.” He said it innocently. But he remembered that. He’s a policeman now. A few years ago he came back and told my husband he was sorry for what he had said to us.

In 1971, the family moved to a new two-story home in La Palma. Katie’s children completed their educations. Today, a proud Katie reflects on the survival skills she learned from her mother, now 87.

She has to be the most inspiring, strong person there is. She raised six boys and two girls by herself. Like she always said, primeramente Dios (God first). If you strongly believe, he’ll help you somehow.

But there’s a lot of things she had to do that I didn’t do. She was very obedient, doing everything my father said. After my father was killed, she had a heck of a time selling the property in Mexico because her name was not on the deed.

I don’t know, but I cannot be very obedient. I believe questioning is the best way to get ahead and better yourself.

She fiercely defends her Mexican heritage.

I have relatives that have changed their names. Well, it’s their choice, but I think that I am proud of what I am, where I come from and of knowing two languages.

But the more you know, the more advantaged you are. This is what I tell my children. I’m kind of ashamed to say they don’t speak Spanish the way they should. But I’ll tell you why. In learning to speak English, Spanish became less important at home.

The two older ones can express themselves pretty well. But Bobby, he refused until his last year in high school. “Why didn’t you make me, why didn’t you make me?” he told us.

“How can I make you? And besides, if you want to learn, let’s start right now. Whether in six months, a year, you can learn if you really set your mind to it.”

She reflects on 33 years of marriage.

I never felt I had to be more than a housewife. I’m not a professional, but I learned a lot of things in my life. I’ve worked. I worked as a waitress 11 years. But when any member of the family gets sick, I quit.

My family has always been first, no matter what.

You can be happy with a family, you can be very productive. That’s your happiness, your whole life.’

Maria Elena Gaitan

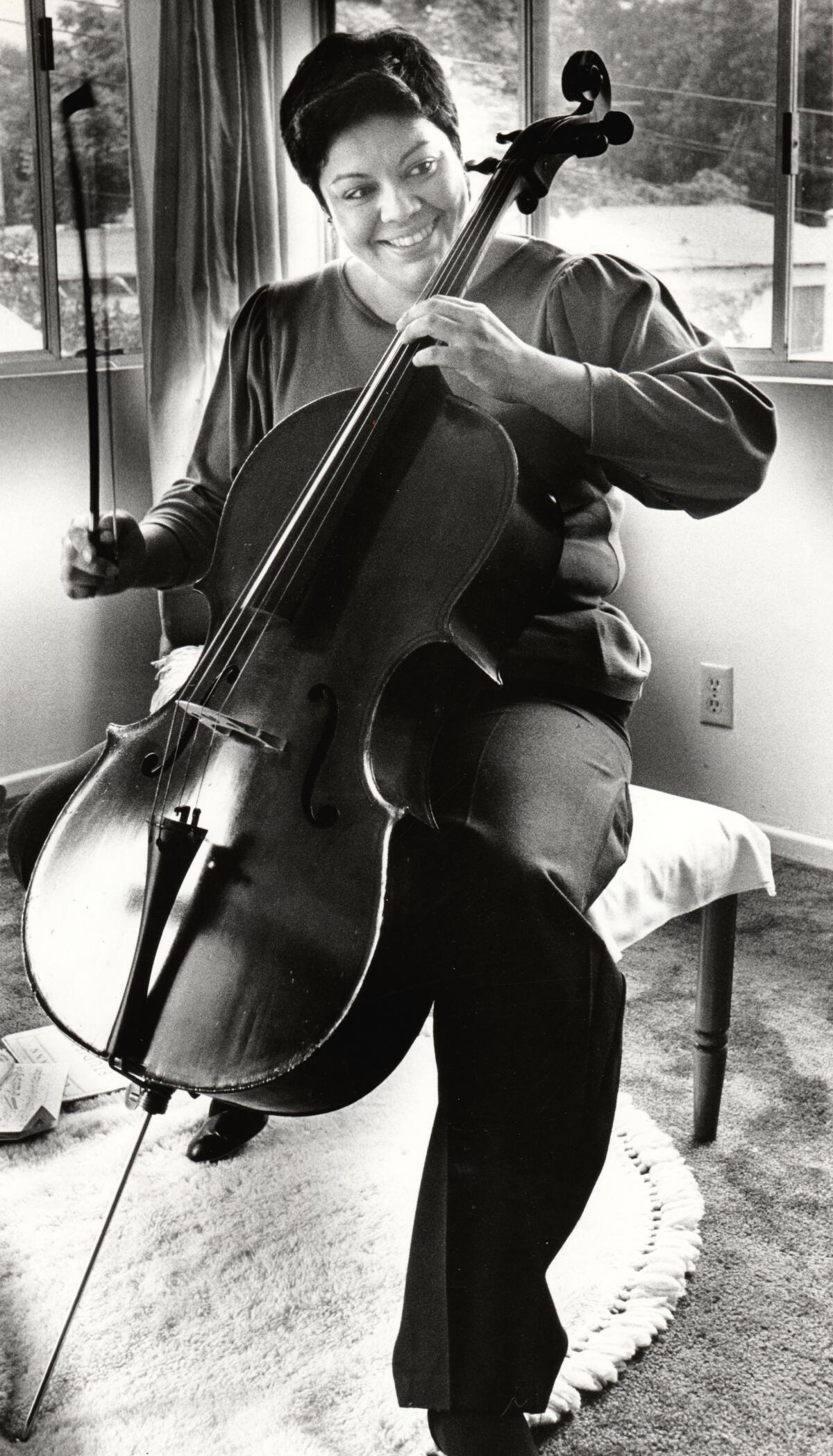

Fifteen years after she was swept up by the Chicano movement, Maria Elena Gaitan, 33, is flourishing as a poet, writer, actress and musician.

She co-authored “La Condicion Femenina,” a play about the Chicana rites of Passage, and is working on a second drama, “The Rape of Teresita Dominguez.”

At 18, Gaitan, a cellist, left the Pasadena Symphony and her studies at what is now the School of Music at the California Institute of the Arts. Instead she marched and lobbied for change in immigration, farm worker and public education policies.

Gaitan has remained active ever since. She has been a candidate for the Los Angeles school board and, at the Hispanic Urban Center, trained parents to be advocates for public education. Her involvement with education diaries on a family tradition. Her grandfather, a teacher, led a literacy campaign in Mexico. Her mother, Ana Covarrubias, a classical pianist and former music teacher in East Los Angeles, was active in bilingual education.

Gaitan works as a legal interpreter and has a monthly radio talk show focusing on Latino education issues. She lives in Glendale with her 7-year-old son, Octavio Tizoc.

My music was a gift from my mother, who gave me my fist cello lesson when she was going through her divorce . . . After I left high school and went to Cal Arts, I was in that enclave of music, but it was incongruous with the tremendous social movements that liere happening among Chicanos as a result of the civil rights movement.

My mother was teaching at Lincoln High School at the heart of where the blowouts (student walkouts) happened. And here I was, in some institutions that were still segregated, like the Pasadena Symphony where I wasn’t prepared for the racism and elitism of the classical music environment. Many of the adults and the rich kids wouldn’t even speak to me. It made me angry, and for me, it became a matter of choosing . . . .I was on the verge of joining the Musicians Union. It was very painful and it’s a crime that I had to make that choice.

As the movimiento began developing, I was simply in it. I was in the marchas; I would fast (for the farm workers). I saw the Chicano movement at its height and at its fullest, with all its victories, its opportunism, its male supremacy and its rip-offs . . .

I was in the farm workers movement because the idea of my people being campesinos and being exploited was the most enraging of all, that we could be the ones that picked the food and they were calling me a “beaner” at (mostly white) Alhambra High School. . .

There’s a Part of me that hates high school because they took my budding person and tried to squash it. Racism can be so brutal. We can’t live in this country and not be affected by it.

‘Sometimes I think, “Well, l’m a victim of racism. How do I fight back and not die?” One way is through the arts. When the insanity gets to be too much, a prisoner writes a poem.’

— Maria Elena Gaitan

But I’m not a segregationist. Segregation has been the most critical strategy to keep us apart, isolated and subjected to inequality. The very fact that a society can create nuclei of ghettos and barrios is not something we should romanticize and say, “If it wasn’t for the barrio, we wouldn’t have culture.” Hey, we have culture in spite of the inequities in the barrio and in spite of segregation.

Sometimes I think, “Well, I’m a victim of racism. How do I fight back and not die?” One way is through the arts. When the insanity gets to be too much, a prisoner writes a poem.

Two casualties of racism, she observes, are self-image and self-expression.

Racism affects self-image because if everything that you see does not reflect your type, your beauty, what you are, it means that somewhere along the line, someone is deciding that you are not beautiful, capable or worthy. If we hear this long enough, it succeeds in convincing us. That’s what fads are all about. You put something out and bait people with it. I hate seeing Chicanas with blonde hair when their skins are not of that color. They do it to look more European and less Indian. It’s an aspect of self-hatred that’s real evident to me. Chicanos have to stop being afraid of their own strength and beauty tambien.

The way that racism affects self-expression, quite simply, is that it doesn’t allow us to learn reading and writing skills the way we should. Most of us are in public schools. Most public schools are segregated and most segregated schools are also overcrowded.

That’s why the collective ability of Chicanos, the ability of kids of color to read and write, is minimized.

It’s quite natural that some of us can’t read and write because of how we went into the classroom-many of us speaking Spanish first-and how vioIently the public school place took away our ability to communicate by forbidding us Spanish.

In 1981, Gaitan attended the Third World Congress of Women sponsored by the Women’s lnternational Democratic Federation in Prague during the U.N. Decade of Women.

People all over the world are interested in us. They know what Chicanos are...

(At the congress) I saw women of every color from every country speaking every language...

I thought, “When I go home, I’m going to try to use my resources better than I have because, my God, how do those Palestinian women, those women in South Africa and El Salvador, get up in the morning and face life?”

Because Chicanas are among the most exploited workers in the country, it’s more essential for them to be in touch with what goes on in the whole world. That way, they will understand what their position in this society is and fight for their equality.

They will understand there is a history of struggle. They don’t have to reinvent it. A Chicana doesn’t have to do anything but be active where she is because she affects those around her, her family, her workplace, the politics that go on here.

She has power because she’s a fundamental part of the productive society. When Chicanas realize this, hey, honey, I’ve got news for you. They’ll be real angry about how unequally they’ve been treated and exploited.

When they understand that they had rights this whole time that they were unable to exercise because they weren’t given the knowledge of them—when Latin women get that — those sewing machines (in garment factories) might stop. They might get real mad one day and those houses will not be cleaned and those thousands and thousands of beds in all the motels across the land may just not be made and then we’ll see where you are.

Despite these conditions, Gaitan refuses to be bitter.

The lack of material things around you, the difficulty of sustaining your life, starving, all of it, can force you to be inhuman.

But, I learned from black women that when you’re attacked with hatred and racism, the first thing you must not do is lose your ability to love.

This is the noble nature of suffering, and I’m not glorifying it, but I really do believe that people who have gone through a lot of oppression and suffering—like black people, Mexican people, Indian people, poor people—have had to develop a special dimension of love.

We have to raise the level of expectations in people. We don’t want them to stop hoping, to feel weak or to give up meekly, thinking that they have no resources at all.

And, you know what? I expect my people to have jobs. I expect to make money, too. How can I have any expectations for my people if I don’t have any for myself?

This story appeared in print before the digital era and was later added to our digital archive.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.