Latinos: A diverse group tied by ethnicity

- Share via

Daniel and Maria Elena Castro were in the forefront of the 1960s Chicano political and social movement.

They felt so strongly about the Mexican/Chicano culture that they named their son Quetzalcoatl after the Aztec god and their daughter Tonantzin after a Mayan mother of the gods.

To their chagrin, they discovered two years ago that Quetzalcoatl, then 5, was losing the Spanish language and Chicano culture after entering a Pasadena private school, where he was the only Latino in class.

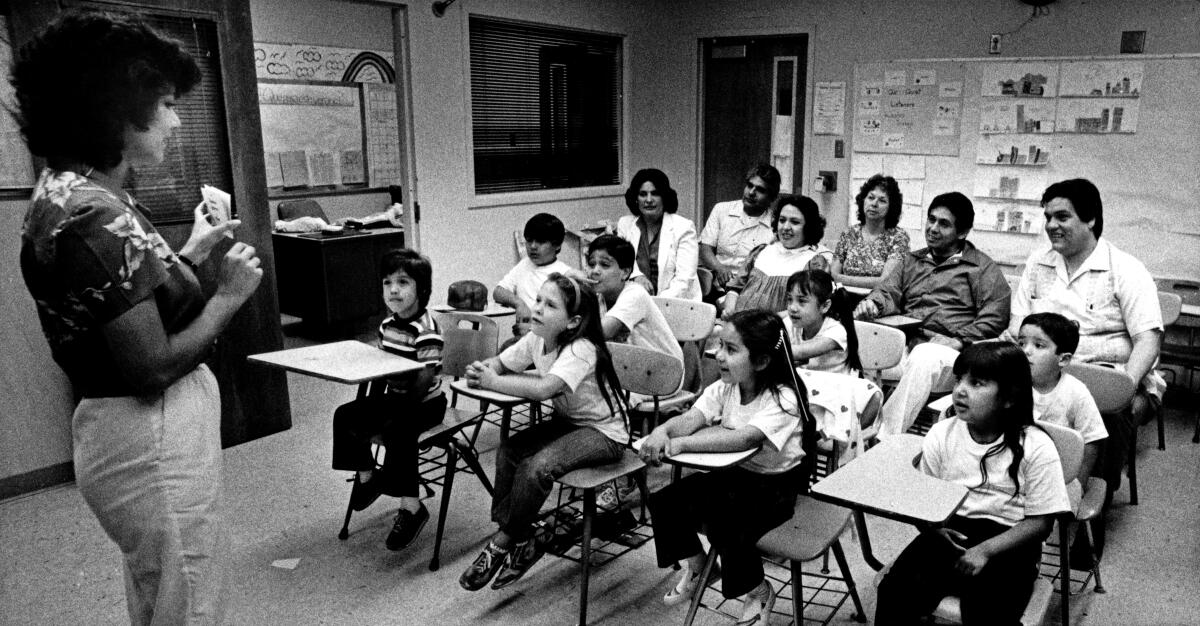

They met with Chicano parents facing similar dilemmas and decided to set up Resolana, a Saturday morning school where their children would be taught Spanish and la cultura.

“We all had the intent to raise our children as Chicanos,” said Castro, 38. But the parents found out that, after using English in their job, “it was hard to switch to Spanish ... maybe out of laziness,” Castro said. “We needed to have other people reinforcing.”

The Resolana parents reflect one element of the Latino community of 2 million people in Los Angeles County, a population of vast economic, social and cultural diversity.

More than 1.6 million of the county’s Latinos are of Mexican origin, according to the 1980 census, ranging from descendants of settlers who came to California when it was part of Mexico to newly arrived immigrants. A growing wave of Central American refugees is adding to the diversification of the Latino population, which also includes Puerto Ricans, Cubans and South Americans.

Despite economic and political differences among — and within — the groups, Latinos share important cultural traits and most share the Spanish language and Roman Catholic religion. They want to be part of the national economic and social life without having to give up their ethnic identity or culture.

“Few groups have had as consistent a history of collective identity, of pronounced preferences for ethnic group labels and of resistance to assimilationist forces,” said social researcher Carlos H. Arce.

“Latinos retain a lot of our culture and identity, and we want to pass that along to our children,” said Felix Gutierrez, a USC journalism professor and fifth-generation Angeleno.

In such Chicano barrios as East Los Angeles, or in the Pico-Union district, the “Little Central America” of Los Angeles, the retention of Spanish and transmission of cultural traditions come naturally with the territory.

But those Chicanos who move away from heavily Latino residential areas often must battle the tides of assimilation to retain their ethnic identity.

::

The Resolana parents made a conscious decision to pass on their Spanish-language fluency and Chicano culture in a systematic manner. This attitude is in sharp contrast to the way Daniel Castro was raised.

His parents, who had suffered discrimination because they were Mexican, decided in the late 1940s that the best way for their children to advance in the Anglo-dominated society was to speak only English.

That approach was typical of the “survival strategy” that many Mexican-American families adopted to cope with discrimination.

“But Mexican-Americans found out that they could be assimilated and it didn’t make any difference. They still suffered discrimination,” said Castro, a Pasadena businessman who has a doctorate in sociology from UC Santa Barbara.

“People tried to change their name, their religion, their culture, but they couldn’t change their skins,” Castro said. “Once you come to a realization that I am what I am, then it’s easier to live with yourself.”

The Castros and some of the other Resolana families live in predominantly Anglo, middle-class neighborhoods. Resolana gives their children the contact with other Chicanos and the bilingual training that they would otherwise miss.

Yolanda Gonzalez, a teacher at a Lincoln Heights elementary school, conducts the Saturday morning classes. “The Japanese, the Armenians and other ethnic groups have their special schools,” she said, “but this is the only Chicano family school that I know of.” She hopes other Latino parents will follow the model of Resolana.

After two years of classes, the parents say they see a pride in their children, who range in age from 5 to 7, for the Latino heritage and a growing knowledge of Spanish. They also consider the school important for leadership development. “Someday, we hope to hold a celebration for the first governor [of California] to have come out of the Resolana school,” Castro said.

Most of the Resolana parents are college graduates and are in business, law, education or government service. They are a closely-knit group, but they are diverse in many ways. Like the Latino community as a whole, most are Roman Catholics, but some are Protestants; most are Democrats, but a few are Republicans.

Some, like Resolana parent Antonia Navarro, who traces her family six generations in New Mexico and grew up in Los Angeles, said her parents “never spoke anything but Spanish in the home.”

Others, like Castro, did not learn Spanish from their parents but picked it up from friends in the barrio and spoke a slang “Spanglish” (a mixture of Spanish and English) with them. At UC Santa Barbara, where he was active in the Chicano movement, Castro said, his first Spanish course was one of his most difficult experiences because the teacher automatically expected him to know Castilian Spanish.

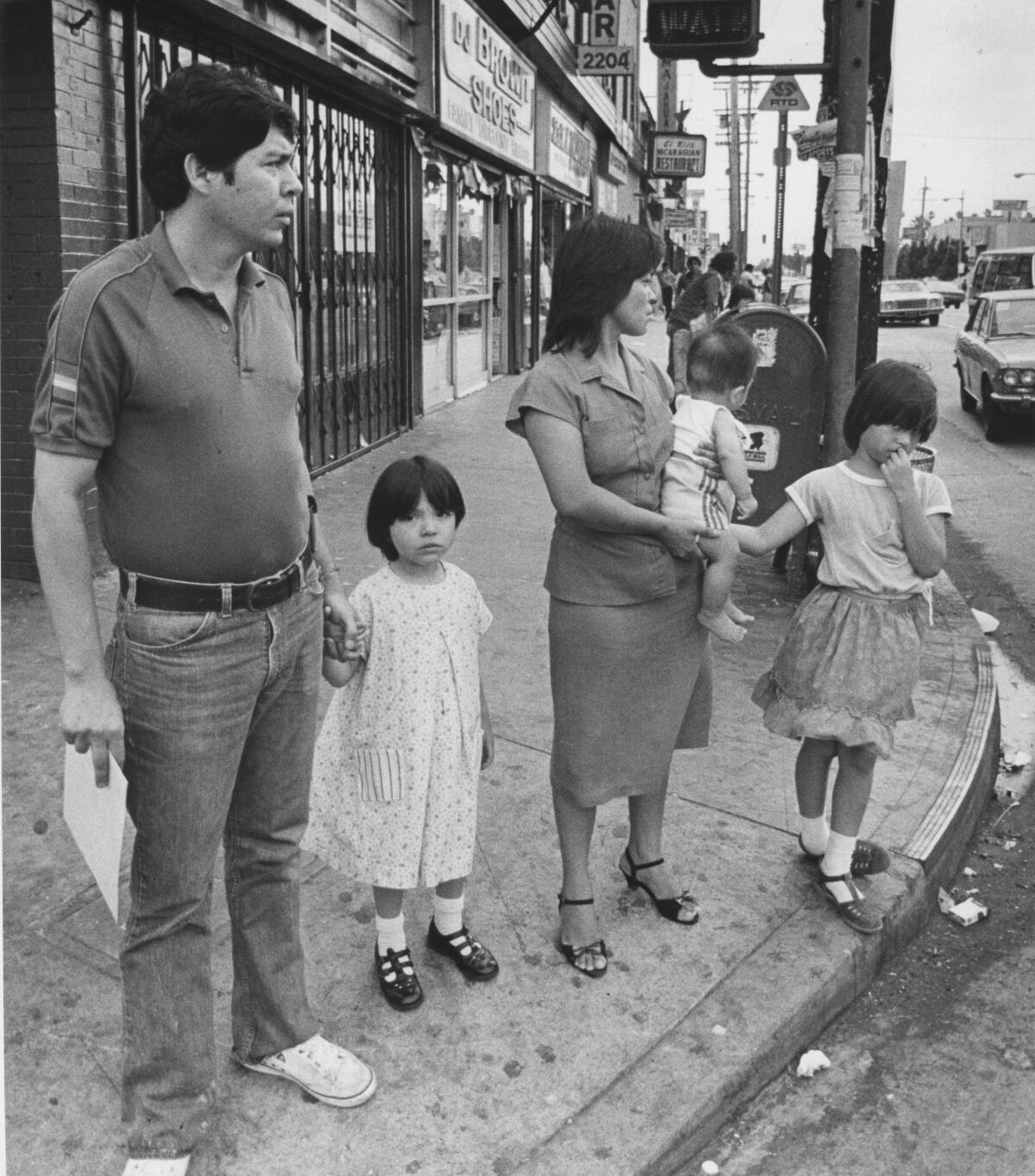

At the other end of the Latino spectrum are the refugees streaming into Pico-Union after feeling the revolutions, violence and poverty of Central America.

The Pico-Union district and adjoining Alvarado corridor near Los Angeles’ MacArthur Park, populated just five years ago by blacks, Latinos and Anglos, is now thoroughly Central American. Restaurants advertising pupusas, a typical Salvadoran tortilla-based dish, Guatemalan bakeries and Nicaraguan shops form a collage along West Pico Boulevard between Union and Normandie avenues.

A majority of the estimated 450,000 refugees in Greater Los Angeles have settled in the small apartments or duplexes in Pico-Union, according to Francisco Rivera, an official of the El Rescate refugee agency in the area.

The exact size of the Central American population is unknown, primarily because most came without immigration papers and since the 1980 census was taken.

Rivera and others in the refugee community estimate that there are 300,000 Salvadorans, about 6% of El Salvador’s population of 5 million. He estimates the Guatemalan population at 100,000, with 50,000 Nicaraguans and other Central Americans also living in the Los Angeles area.

The refugees need not worry about retaining their culture. Their concerns deal primarily with survival — jobs, housing and food.

In the tiny apartment of Joaquin and Mercedes Romero, in the middle of Pico-Union, Spanish is the only language. The Romeros never studied English and never thought they would have a need for it. But that was before war erupted in their Salvadoran homeland.

Joaquin Romero, a news photographer for the Associated Press, was wounded seriously in the right leg outside San Salvador in April 1981. He later accused government soldiers of firing at him and fellow journalists. Colleagues advised him to leave El Salvador for fear that the soldiers might retaliate against him.

He made it to Miami on a U.S. visa because of his need for medical treatment. He tried to get visas for his wife and family but he was refused by U.S. officials. So there was no way to get his wife and two daughters into the United States except illegally.

The family depleted eight years of savings and paid a “guide” $2,500 to get plane tickets to Tijuana and show the mother and daughters the way across the U.S. border.

“In Tijuana, we waded across a river filled with mud and garbage,” Mercedes recalled recently, speaking softly in Spanish. “We got across the border by climbing a series of fences. We ran for five hours in the night hiding when we heard helicopters above us and almost dying of fear.”

When the Romeros were finally reunited in Los Angeles, they started a new life with literally only the clothes on their backs.

“There would be days when we wouldn’t eat,” Mercedes Romero said. “We got a few candies and gave it to the girls. ... There were no neighbors, no friends. I felt like a prisoner. I cried alone.”

They barely got by for months with odd jobs. Mercedes gave birth to their third child last December. They named the boy Oscar Arnulfo Romero in honer of the assassinated Salvadoran bishop. By virtue of his birth here, he is a U.S. citizen.

In a recent weekly paycheck, Joaquin Romero, 32, took home about $40 for 16 hours’ work as a restaurant kitchen helper. He is hoping to work more hours in the coming weeks, and Mercedes is doing housecleaning, trying to make ends meet.

The fear of being caught by immigration agents and being deported is ever-present. “Everywhere we go, we worry about it,” Joaquin said.

Even in the heavily Salvadoran Pico-Union area, they have few friends. And they don’t understand why some Mexican Americans, their cultural brethren, don’t even speak Spanish.

The closest the Romeros get to a feeling of a Latino community is during the mariachi Mass at the Catholic Church across the street from the Olvera Street Plaza, the city’s birthplace. The congregation is primarily Mexican and Salvadoran but includes Latinos from practically all countries. The Romeros find spiritual and cultural support in hearing the familiar liturgy recited in Spanish, 2,300 miles from their homeland. The Romeros yearn to return to El Salvador. But until they can, they want to lead productive lives here. They want their two daughters, 8 and 6, to learn English, “but we never want them to forget their Spanish. We want them to remember that they are Salvadorenos.”

::

Hacienda Heights, an attractive hillside community south of the Pomona Freeway, seems a world away from Pico-Union. It is dubbed by some the “Chicano Beverly Hills.”

Claude Martinez likes the “good family environment” of Hacienda Heights, but says the suburban setting is a “challenge for those of us who want to raise our children and keep them aware of their cultural heritage.”

Martinez and his wife, Norma, say they are “transmitting the Latino culture to our [two teenage] daughters, but not exactly as our parents did because we have lived different experiences. It’s true for everyone, not just Hispanics.”

Claude and Norma Martinez grew up in different areas of East Los Angeles. She has always been bilingual, but Claude says he lost a lot of his Spanish in a predominantly Anglo parochial school. Like many Mexican-Americans, he said, he feels more comfortable speaking English.

“In the 1960s, a lot of us tried to use language as a determinate of ‘how Chicano are you?’” Claude Martinez said. “The thinking was that you were more Chicano if you spoke Spanish than if you didn’t. I think that’s wrong.”

What he and his wife are passing on to their daughters, he said, “is a bicultural heritage — a way of looking at things, such as close family relationships.”

The Martinezes decided to move into Hacienda Heights after they visited Norma’s brother, Edward Martinez, who has lived there since 1976. The move eastward from Boyle Heights and East Los Angeles has been an increasing phenomenon for Mexican-Americans for the last 35 years.

In the 1940s, when Norma and Edward were growing up, their family tried to move into a larger home in Monterey Park but were rebuffed. “It was a traumatic experience for our parents,” Edward said. “They found out that they were [not] allowing Mexicans into the area no matter how much money you had.”

The family was finally able to move there in the late 1950s.

“It was hard to leave my roots in East L.A. I left a lot of friends there,” Norma said.

But she and her husband remain close to East Los Angeles. Claude, 44, is executive director of El Centro Human Services Corp., a nonprofit agency that provides mental healthcare and social services to Eastside residents.

Discussing their experiences recently, several Latino residents of Hacienda Heights expressed irritation at suggestions that they have abandoned the Latino community simply because they moved to the suburbs, rather than staying in East Los Angeles or another barrio.

“We still have a commitment to the [Latino] community,” said Edward, a Los Angeles County community development official and past president of the County Hispanic Managers’ Assn. “Moving to a good environment for our children doesn’t mean you forget about social issues.”

Claude Martinez said he does not feel Latinos should have to apologize for living in Hacienda Heights and similar communities. But he admitted that many Chicanos are sensitive about the subject and often get defensive.

“We often feel that we have to give an apology for success,” Claude said. “To say, ‘I paid my dues. I went in bare feet when I was a kid. ... Now I deserve this.’”

Edward Martinez said he would like his two children exposed to as much ethnic diversity as possible. “There are Hispanics and Asians in Hacienda Heights,” he said, “but little diversity among economic classes. Most are middle class or upper-middle class. That’s the downside of living in Hacienda Heights.”

However, both Martinez couples say they consider Hacienda Heights not as an isolated area but as part of the culturally rich and exciting Los Angeles area. And as Claude Martinez put it:

“To be Latino in Los Angeles is as close to heaven as you can get.”

::

Of the Latinos who were gathered at Edward Martinez’s home for the recent discussion, Polita Huff had made the most conscious effort to pass on the Spanish language to her children.

Huff learned Spanish from her mother, who was born in the Mexican state of Sonora. Her father is of Irish ancestry. Her husband is Anglo and does not speak Spanish.

“I spoke to our two children strictly in Spanish until they were about 3,” she said. “I wanted to pass on that cultural uniqueness — the Spanish language — to them.”

The language and culture were not lost in two generations of Latino-Anglo marriages in the case of Huff. The same is not always true; it is an individual or family choice, of course.

Nationwide, about one of every six Mexican-Americans who marry chooses a non-Latino partner. Studies have shown that Latinos who attend college are more likely to marry non-Latinos than those who do not have that experience. Also, the proportion of Spanish-surnamed women who marry non-Latinos is higher than among men.

Studies of Anglo-Latino marriage have shown two views on the subject by Mexican-Americans. Some contend that the Latino cultural imprint is diluted or lost in such marriages, but others feel that they give children the “best of two worlds.”

At the Hacienda Heights discussion, Oscar Ruiz said he had never thought of his marriage “as an intermarriage.” He started dating Terry Youngs when they were high school students in Monterey Park and his Mexican-American descent had never been an issue, he said.

“We feel that our children have gotten a bit from each of us,” Terry said.

Their daughter, 12, “knows about her [Latino] culture,” Oscar said. “But with our 10-year-old boy, it’s just not an issue with him. He sees everyone alike. ... I want him to realize that he has a heritage. I don’t want to lose that culture.”

::

In addition to family ties, a whole network of Spanish-language publications, radio, television, films and other media provide a foundation for the Latino culture. For example, 10 local radio stations do at least some of their programming in Spanish, and there are dozens of Latino arts groups and hundreds of social and cultural organizations.

This helps provide unifying forces for Latinos. But cultural similarity does not translate into unity in politics or across economic classes.

Friction sometimes occurs among Chicanos, Mexicanos and Central Americans competing for the same jobs. “It’s a very normal reaction,” said Father Luis Olivares of the Old Plaza Church near Olvera Street. “People deprived of job opportunities feel a new threat from immigrants.”

In the field of politics, observers point that Latinos do show unity on some issues, such as the importance of education. They believe that the lack of agreement on other political matters is to be expected in a heterogeneous community.

With the growing importance of Latin America in U.S. foreign policy, Father Loren Riebe of St. Thomas the Apostle Catholic Church believes the Central Americans will help “bridge the incredible gap — culturally and politically — between the United States and Latin America.”

The connection between the Mexican-American and Central American communities is not a strong one yet.

Carlos Ugalde, a Glendale College professor, complained that most Chicanos do not have a commitment to aid the revolutionary cause in Central America. The reason for this, he believes, is that the U.S. educational system teaches students little about Latin American and that Chicanos have no understanding of “anything south of Mexico.”

Riebe, whose church is in the Pico-Union area, points out that Mexican-Americans are still trying “to get together” within their own community and are dealing with issues closest to them, instead of matters that are of greater concern to the Central Americans.

On the other hand, the Salvadorans and other Central Americans remain emotionally attached to their homelands. Rivera, a Salvadoran who has worked at El Rescate since 1981, believes that 80% of the refugees would return to their countries as soon as they knew it was safe.

But Riebe said that some refugees have established roots here. “There’ll always be a lot of coming and going now that they’ve established a base here,” he said.

Daniel Castro said he feels a kinship with new immigrants from Mexico and Central America but does not expect much interaction with them because “we just don’t have the same interests.”

Felix Gutierrez of USC foresees a “strong leadership group coming out of the children of the undocumented workers.” Many of them were born in this country and will learn the system, he said. “They will be the ones who will push the Chicanos who have penetrated the institutions once closed to us.”

Reina Orella, a young Salvadoran who arrived here earlier this year, said there are significant differences among Latinos, even in the way various groups of Latinos speak Spanish. But she added: “We might have our disagreements, our problems, but that is true of all human beings. We are Chicanos, Mexicans, Salvadorans. But we are all Latinos.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.