- Share via

The headline was stripped across the top of the front page, “Marauders From Inner City Prey on L.A.’s Suburbs.” The story, published by The Times on July 12, 1981, described a “permanent underclass” in the city’s “ghettos and barrios,” fueling a crime wave that was spilling over from South Los Angeles into prosperous — and largely white — communities in Pasadena, Palos Verdes, Beverly Hills and elsewhere.

The article, the first of a two-part series, purported to be an ambitious look at a major social problem, and it cited a lack of education and jobs as underlying causes of inner-city distress. But it also reinforced pernicious stereotypes that Black and Latino Angelenos were thieves, rapists and killers. It sensationalized and pathologized the struggles of poor families and painted residents of South L.A. with a broad brush. It quoted police and prosecutors unskeptically and implied that more aggressive policing and harsher judicial sentencing were the only effective responses to crime.

For the record:

10:18 a.m. Sept. 28, 2020An earlier version of this story identified Dean Takahashi as a Metro reporter in 1992. He was a business reporter.

The story lacked nuance and context, neglecting decades of government policies that had led to housing and school segregation and to the creation of ghettos and barrios, which were then provided with inferior public services. And it failed to give any real sense that the vast majority of the area’s residents were ordinary, law-abiding citizens, just trying to raise families and get by.

The series drew prompt and deserved criticism that highlighted an insidious problem that has marred the work of the Los Angeles Times for much of its history: While the paper has done groundbreaking and important work highlighting the issues faced by communities of color, it has also often displayed at best a blind spot, at worst an outright hostility, for the city’s nonwhite population, one both rooted and reflected in a shortage of Indigenous, Black, Latino, Asian and other people of color in its newsroom.

Our reckoning with racism

As the country grapples with the role of systemic racism, The Times has committed to examining its past. This project looks at our treatment of people of color — outside and inside the newsroom — throughout our nearly 139-year history.

Prompted by a pandemic, an economic crisis and a national debate over policing — all of which have spotlighted racial disparities in the United States — our nation now faces a long-delayed reckoning with systemic racism. We would be remiss, in the autumn of 2020, a season of grief and introspection, if we did not take part in that self-examination. This editorial is one part of that process.

•••

A comprehensive and balanced history of Los Angeles journalism — a people’s history that tells the story of The Times from the perspective of its employees and its readers — has yet to be written. But a deep look at the paper’s pages over time tells part of that story.

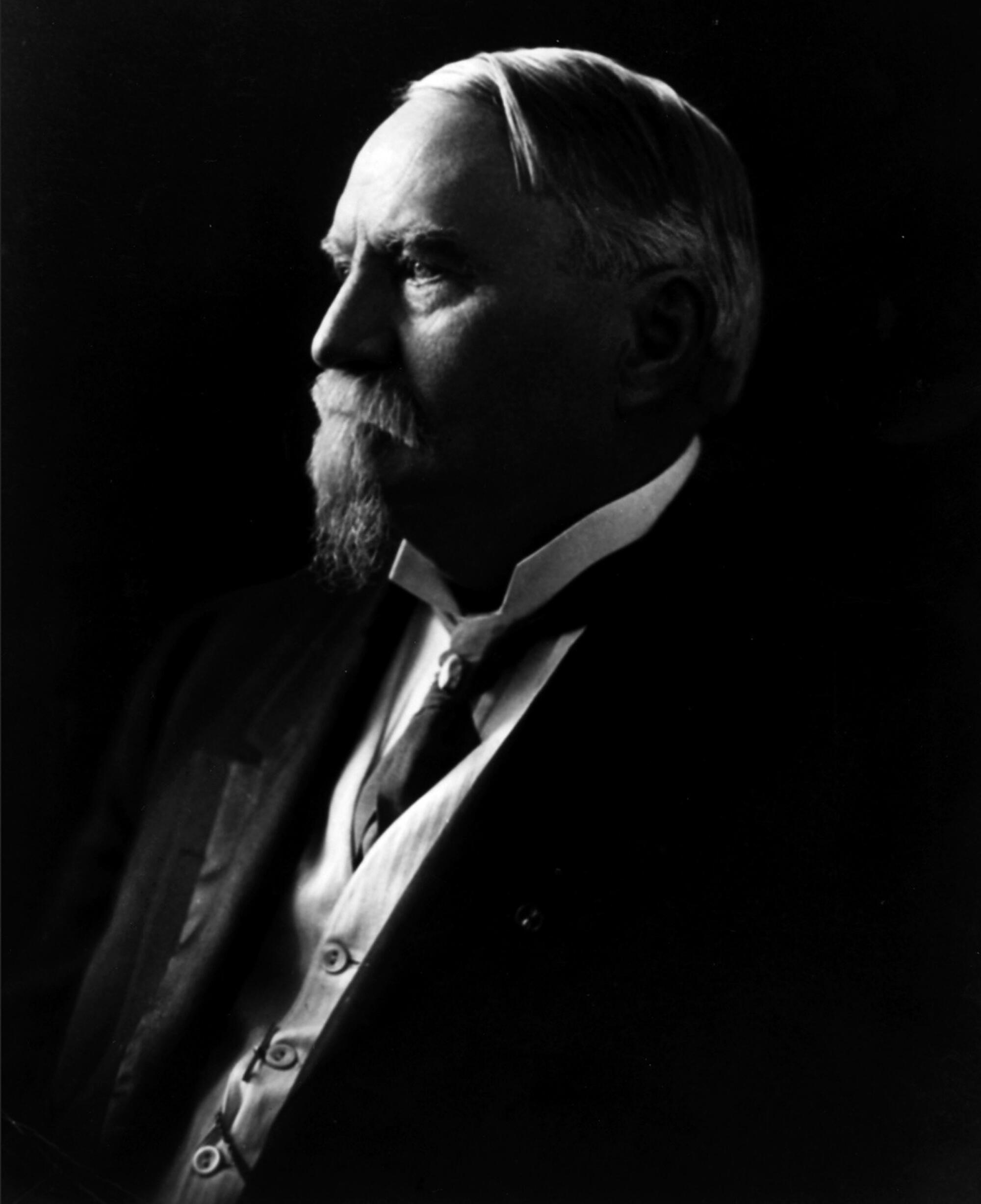

For at least its first 80 years, the Los Angeles Times was an institution deeply rooted in white supremacy and committed to promoting the interests of the city’s industrialists and landowners. No one embodied this aggressive, conservative ideology more than Harrison Gray Otis, the walrus-mustachioed Civil War veteran who controlled The Times from 1882 until his death in 1917.

The modern notion that journalism’s core precepts include uncovering hard truths and exposing inequity would have been foreign to Otis and other press barons of the last Gilded Age. Far from a mission of “comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable,” his newspaper stood for the raw exercise of power, and he used it to further a naked agenda of score settling, regional boosterism, economic aggrandizement and union busting.

Otis was a Lincoln Republican who had fought on the side of the Union and opposed slavery. But his Times was a newspaper aimed at the mostly Protestant white settlers who migrated to California from the Midwest and the Plains in the decades after it was seized from Mexico in 1848 and admitted to the Union in 1850.

Again and again, The Times sought to shape and dominate the region instead of merely chronicling it. Using a trade group known as the Merchants and Manufacturers’ Assn., Otis spearheaded a campaign to prevent and impede unionization. He weighed in on the side of San Pedro over Santa Monica in an epic 1890s battle over where to locate a federally funded deepwater port. His family meddled in the politics of Mexico, where they owned a huge ranch, in an attempt to preserve their land rights. He was part of a powerful syndicate that pushed for the acquisition of water rights from farmers in the Owens Valley in 1913 — a decision fictionalized in Roman Polanski’s 1974 film “Chinatown” — and the annexation of the San Fernando Valley in 1915.

And in all of his crusades, he enlisted the powerful voice of his newspaper.

During the early 20th century, as control passed from Otis to his son-in-law Harry Chandler and his heirs, The Times promoted the city’s explosive growth. But even as Dust Bowl migration, the World War II arms industry and a vast movement of Black Americans escaping Jim Crow segregation transformed the city, the newspaper remained nearly entirely white in its staff, its readership and its outlook.

A tragic example of why that was a problem was the newspaper’s support for wartime incarceration of Japanese Americans, one of the most egregious violations of civil liberties in our nation’s history. (The Times apologized in 2017 for that editorial position.)

Here’s another example: In 1943, sailors on leave from wartime service rampaged lawlessly in downtown Los Angeles, attacking young Mexican Americans fitted in so-called zoot suits — long coats and wide trousers pegged at the ankle. The Times largely ignored the context — the social and economic upheaval brought about by wartime mobilization and the racist trope of threatened white womanhood — and blamed the victims instead of their assailants. When First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt suggested that the rioting might have grown out of racial discrimination toward Mexican Americans, The Times vehemently denied that was possible, asserting in an editorial, “We like Mexicans and we think they like us.”

After the war ended, The Times became an uncritical mouthpiece for Washington as it covered the Eisenhower administration’s Operation Wetback, which used military-style tactics to deport Mexican migrants — some of them U.S. citizens — who had been invited north to perform agricultural labor during the war.

The most enlightened of the Chandlers was Otis, fourth and last of the patriarchs who controlled The Times for its first century. The Times’ standards and reputation improved under his tenure as publisher, from 1960 to 1980. He plowed what were then vast profits into the hiring of hundreds of journalists and reoriented the paper in a more politically neutral direction. Famously, Chandler authorized the publication, in 1961, of an investigation into the anti-communist John Birch Society, whose members included far-right white supremacists — and members of Chandler’s extended family (though he also presided over the paper’s 1964 presidential endorsement of Barry Goldwater, who strongly opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act).

By the standards of his time, Chandler was a moderate, if not always consistent. He endorsed most goals of the civil rights movement and in 1965, during the Watts uprising, served as an informal mediator between Black protesters and the Police Department. In 1969, The Times endorsed the historic mayoral candidacy of Councilman Tom Bradley, a grandson of slaves who in 1973 would go on to defeat Mayor Sam Yorty, the divisive white incumbent.

But even as The Times moved in a more progressive direction, its newsroom did not come close to representing the city’s demographics. The Times won a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the August 1965 civil unrest in Watts, yet the reporters and editors on the story were nearly all white. A 24-year-old Black advertising messenger, Robert Richardson, covered the disturbances, driving to the scene and phoning in his reports. Named a reporter trainee after the riots, he was given next to no support and left the paper the next year.

“The View From Watts,” an in-depth series The Times published in October 1965, chronicled pent-up frustrations in the Black community, and an accompanying editorial recommended summer jobs, improved police-community relations, stronger school nutrition programs and similar reforms. But the project too often took a patronizing view of Black Angelenos, most egregiously in a piece called “Police Brutality: State of Mind?” that used selective examples and unexamined quotes from police officers to heavily imply that police brutality was a thing of the past.

The Kerner Commission, impaneled to study the root causes of 1967 uprisings in Detroit, Newark, N.J., and other cities, was prophetic in calling for the hiring of Black journalists. “The scarcity of Negroes in responsible news jobs intensifies the difficulties of communicating the reality of the contemporary American city to white newspaper and television audiences,” the panel found. That was certainly true at The Times.

It was not just that The Times saw fit to hire white men almost exclusively for its newsroom; the stories it told were largely for and about white people, which meant Angelenos weren’t getting an accurate account of their city, region and state at a time of rapid change.

Typical of the paper’s attitude was a 1978 interview in which Otis Chandler airily dismissed Black and Latino readers: “It’s not their kind of newspaper. It’s too big, it’s too stuffy. If you will, it’s too complicated.”

Chandler later stepped back from that, saying the paper was looking for readers in the “broad middle class” and “upper classes” regardless of race or ethnicity. “We are not a paper that’s sought after in the lower-class areas,” he said.

Around that time, in 1979, The Times was slow to cover the shooting of Eula Love, a 39-year-old Black homemaker who was shot to death by Los Angeles police officers in her South L.A. frontyard in a dispute over an unpaid gas bill. L.A.’s afternoon daily, the Herald Examiner, played the story big, and Black residents were outraged at what they saw as an egregious example of police abuse. After being hammered by other media outlets for underplaying the story, including in an Esquire article headlined “Mr. Otis Regrets,” The Times ran a long story by media writer David Shaw about how it had “muffed” the story, and top editors began rethinking how the paper covered the LAPD.

As has often been the case in history, progress came from the bottom up. After the “marauders” series, Black reporters met with Editor William F. Thomas to register their objections. And in February 1982, a pioneering group of Latino journalists, gathering for pizza and beer in Downey, began conceiving of a staff-led effort to tell a rich and deep narrative of their growing community. “We keep seeing the same damn stories in the paper: about crime, gangs, illegal immigration,” Frank O. Sotomayor, one of the editors on the series, recalls his co-editor, George Ramos, saying. “We want to tell our stories.”

The result was a landmark series, published in 1983, about Latinos and how they were reshaping Southern California. Latino journalists initiated and carried out the project, and presented the Latino community in all its complexity, featuring gang members and wealthy entrepreneurs, priests, police officers, university students and politicians. It examined issues that impeded Latino progress and celebrated improvements. The project was recognized with the 1984 Pulitzer Prize for public service, the highest honor in American journalism. The same year, The Times’ parent company, Times-Mirror, established a Minority Editorial Training Program, or MetPro, which continues to this day.

Yet The Times remained a lonely place for journalists of color. In December 1990, Shaw, The Times’ media critic, wrote a series lamenting the dearth of diversity in journalism. He wrote of his own newspaper: “The Times is widely regarded — particularly by blacks, inside the paper and out — as having one of the poorest records for minority advancement of any major paper in the country.”

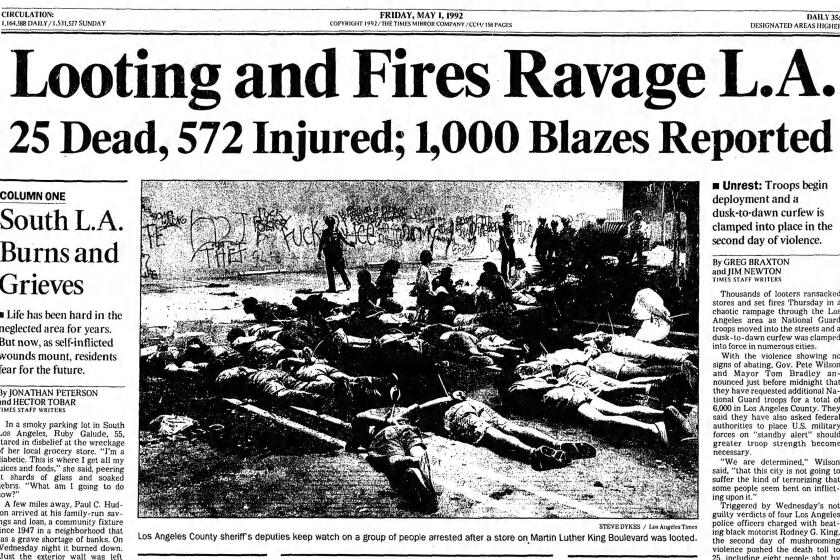

The police beating of Rodney G. King in 1991, and the unrest that followed the subsequent acquittal of the four LAPD officers charged with assaulting him, exposed once again why that mattered. With 63 people dead, the 1992 uprising was far deadlier than the earlier Watts riots, in which 34 people died.

The Times was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for its coverage of the disturbances, just as it was after Watts. But in later years academics argued that The Times overemphasized the role of Black Angelenos in the riots (half of those arrested by the LAPD were Latino) and sensationalized Black-Korean conflict (a Korean-born shopkeeper, Soon Ja Du, had killed a Black teenager, Latasha Harlins, the previous year inside her family’s grocery store).

Within The Times, newsroom tensions burst into the open. “When the riot spread and it became apparent that a number of white reporters could not gain access to the scene, minority reporters from the suburbs were shipped into the danger zone,” Dean Takahashi, then a young business reporter and one of few Asian Americans on staff, wrote in a May 1992 article for Editor & Publisher that drew national attention. “A black colleague of mine mockingly called it the ‘Los Angeles Times busing program.’”

As it had a decade earlier, The Times made some commitments to improvements. It hired several journalists of color and established a zoned section known as City Times to cover neighborhoods of South Los Angeles and East Los Angeles that had long been neglected — “the hole in the doughnut,” as editors said at the time. The effort lasted for only three years, folding in 1995.

But even as the editorial staff pushed for broader and better coverage of the city’s diverse communities, the newspaper was being torn by political divisions within the extended Chandler family that still owned the paper, some of whom felt The Times had leaned too far leftward. In 1994, the top business executive, Publisher Richard T. Schlosberg III, directed the editorial board to endorse Gov. Pete Wilson, a Republican, in his bid for reelection.

Wilson was the chief proponent of Proposition 187, an initiative on the same ballot that would decide his reelection. The measure sought to bar undocumented immigrants from access to state-funded healthcare and education. Staff members, especially Latinos, were disgusted. “Under normal circumstances, I would quietly accept that decision and move on. This time I cannot,” Deputy Editorial Page Editor Frank del Olmo wrote in a dissent that ran in the paper. “Because this is not just another political campaign. And the Wilson endorsement is not — as a senior colleague whom I respect tried to convince me — just another endorsement.”

He continued: “For me, a Mexican American born and reared in California and a journalist here for more than 20 years, this campaign is unprecedented in the harm it does — permanent damage, I fear — to an ethnic community I care deeply about and a state I love.”

The summer after voters adopted Proposition 187 (it was later struck down by the courts), Janet Clayton was named editorial page editor, a Black woman and the first person of color to occupy that role. During her nine-year tenure, the opinion pages of The Times evolved to reflect an optimistic, progressive and inclusive political vision. The section won two Pulitzer Prizes, one in 2002 for a series on mentally ill people living on the streets, and the other in 2004 for a series on entrenched problems in California state government.

Halfway through Clayton’s tenure, The Times and its sister papers were sold to the Chicago-based Tribune Co. The new owners brought in two nationally esteemed journalists — John S. Carroll, who had overseen newspapers in Baltimore and Lexington, Ky., as editor, and Dean Baquet, the national editor at the New York Times, as managing editor.

With Baquet overseeing the day-to-day operations of the newsroom, Clayton overseeing the opinion pages (before moving to the Metro section) and art director Joseph Hutchinson serving as deputy managing editor for design, the newspaper for a time had three Black editors on its masthead. Del Olmo was the first Latino on the masthead, and the Mexican-born writer Andrés Martinez was later the second, as editorial page editor.

That diversity — a high point — proved short-lived. Del Olmo, 55, died of cardiac arrest after collapsing in his office at The Times in 2004; Baquet, who succeeded Carroll as top editor, was fired in 2006 after refusing to make more cuts; Clayton, Hutchinson and Martinez all left in 2007.

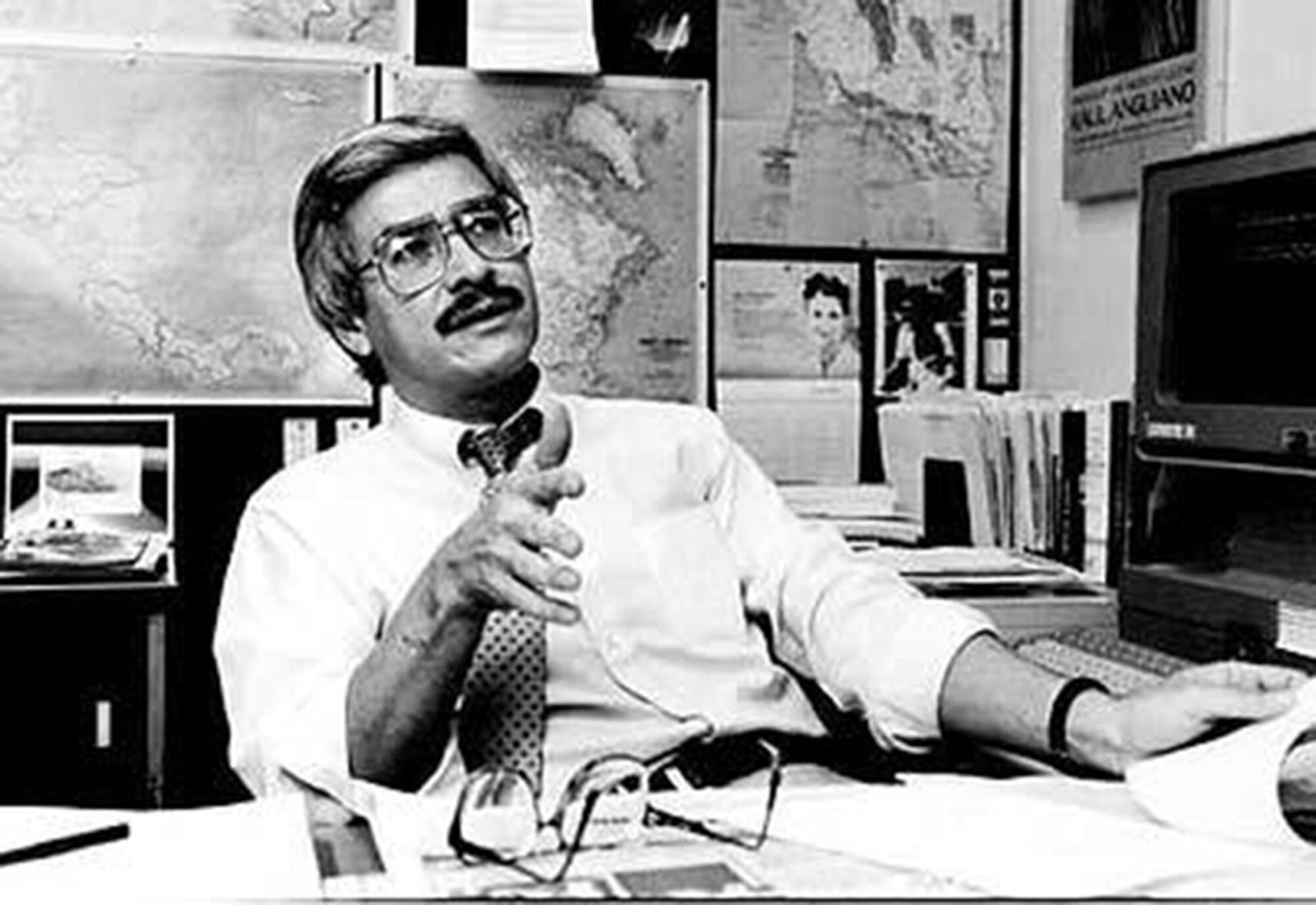

Since Baquet’s departure, The Times has seen a flurry of top editors and business executives come and go. One of them — Davan Maharaj, who joined The Times in 1989 as an intern and oversaw the newsroom from 2011 to 2017 — was of Indian ancestry and an immigrant from Trinidad.

Maharaj, the first Asian American to lead The Times, presided over a depleted newsroom that had spent four years in federal bankruptcy protection, ending in 2012. Newsroom diversity improved, but the staff was shaken by multiple rounds of buyouts. Nonetheless, it continued to do outstanding work, including a Pulitzer-winning expose of corruption in the city of Bell, a story co-written and uncovered by a Guatemalan-born journalist, Ruben Vives.

By the time The Times was sold in 2018, to the physician and pharmaceutical inventor Patrick Soon-Shiong, the paper was down to about 400 journalists, less than half of the 940 when Baquet left.

•••

Where does The Times go from here?

An organization should not be defined by its failures, but it must acknowledge them if it is to hope for a better future.

The brutal death of a Black man, George Floyd, on May 25 while in the custody of police in Minneapolis shocked the world. It also prompted news organizations like The Times to reflect on how they cover, frame and promote stories at a time when the 24/7 news cycle moves faster than ever. Amid nationwide demonstrations over racial injustice, members of the Los Angeles Times Guild established caucuses for Black and Latino employees. The caucuses have called for improvements in coverage, hiring and career development, a public apology for The Times’ poor record on race, and equal pay. They have insisted, rightly, on reframing and recentering our coverage of communities of color.

The Times in 2020 has new owners, new leaders, a new labor union representing its journalists and a new headquarters in El Segundo. But the shadows of the past loom over our institution.

Newspapers are described as a first rough draft of history. But in truth, the first rough draft written by this newspaper — and those across the country — has been woefully incomplete.

On behalf of this institution, we apologize for The Times’ history of racism. We owe it to our readers to do better, and we vow to do so. A region as diverse and complex and fascinating as Southern California deserves a newspaper that reflects its communities. Today, 38% of the journalists on our staff are people of color. We know that is not nearly good enough, in a county that is 48% Latino and in a state where Latinos are the largest ethnic group. We know that this acknowledgment must be accompanied by a real commitment to change, a humility of spirit and an openness of mind and heart.

The Times will redouble and refocus its efforts to become an inclusive and inspiring voice of California — a sentinel that employs investigative and accountability reporting to help protect our fragile democracy and chronicles the stories of the Golden State, including stories that historically were neglected by the mainstream press. Being careful stewards of this new company, privately owned but operated for the benefit of the public, is our first obligation. But that stewardship will also require bold and decisive change. If we are to survive as a business, it will be by tapping into a digital, multicultural, multigenerational audience in a way The Times has never fully done.

We make this pledge in recognition of the many journalists who battled over the decades to make The Times a more inclusive workplace and a newspaper that reflected the real Los Angeles in its pages. As we reorient this institution firmly and fully around the multiethnic, interfaith and dazzlingly complex tapestry that is Southern California, we honor their contributions.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.