‘Alarming’ disparities leave parts of L.A. County hit hard by COVID-19

- Share via

Two years into the pandemic, wealth, poverty and race still dramatically affect the toll the coronavirus takes on people, with Latino and Black communities in L.A. County continuing to be significantly harder hit than wealthier white ones.

Data analyzed by Los Angeles County public health officials showed disturbing inequities in the disproportionate toll COVID-19 was causing for Black and Latino residents, as well as people living in poorer neighborhoods.

The findings underscore how much poorer and largely Black and Latino neighborhoods of L.A. County could suffer should the improvement in pandemic trends suddenly reverse as mask mandates ease, or the need for quick action comes if a new variant emerges.

“These data on hospitalizations and deaths are alarming,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said at a Board of Supervisors meeting on Tuesday. “We have to ensure that our post-surge actions do not widen the gaps by failing to provide additional resources and protections to those at highest risk for COVID-19 hospitalization and death.”

L.A. County will likely lift its indoor mask mandate Friday — a significant acceleration of the expected timeline following changes in federal guidance.

Between Jan. 29 and Feb. 11, for every 100,000 unvaccinated residents in each racial or ethnic group, 74 Latino and 60 Black residents were hospitalized for COVID-19, while 43 white and 30 Asian American residents were.

In other words, unvaccinated Latino and Black residents are at least twice as likely as unvaccinated Asian American Angelenos to be hospitalized for COVID-19.

Those racial and ethnic disparities persisted even among vaccinated people who received their booster shots. For every 100,000 vaccinated and boosted residents, 13 Latino and 11 Black people were hospitalized, while five white and three Asian American residents were.

“These differences partially reflect higher rates of underlying health conditions among Black and brown residents due to inadequate access to health-affirming resources. And they’re also likely to reflect differences in exposure to COVID based on where individuals live and work,” Ferrer said. “Regardless of vaccination status, living in an area with high poverty was associated with a substantially higher risk for hospitalization.”

Many Black and Latino residents, as well as low-income residents, in L.A. County live in areas with less access to resources such as hospitals and pharmacies.

“It’s really clear that where you live and where you work has an impact on your health status. It’s no different for COVID than it is for a host of other illnesses,” Ferrer said at a briefing last week. “Certainly where you live has a tremendous impact on what’s available to help you be as healthy as possible.”

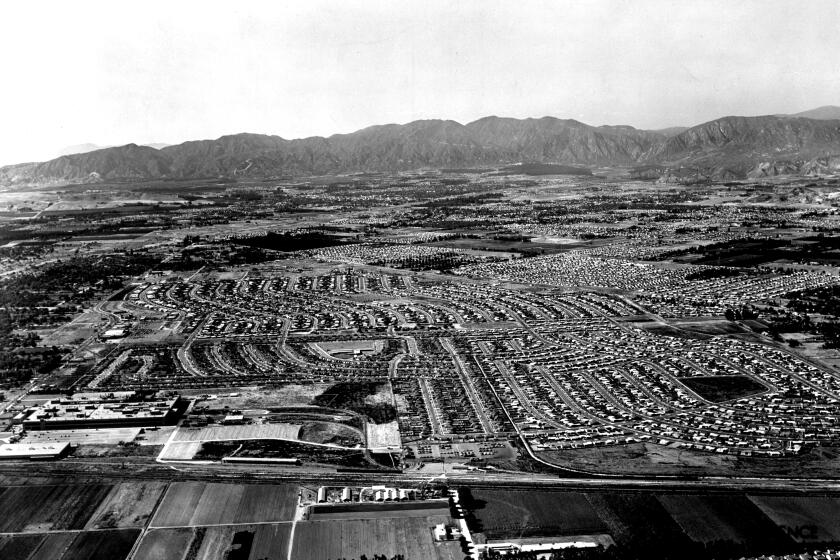

Many Latino and Black residents live in areas where government officials for generations have neglected residents’ public health, in part due to a legacy of racism and discrimination. Neighborhoods such as South L.A., southeast L.A. County and the Eastside are blanketed by a web of freeways spewing toxic pollution, increasing the risk of asthma and other chronic conditions that place those residents at greater risk of COVID-19 complications.

Residents who live in crowded housing, where it’s easier for a highly infectious, airborne virus to spread, are also more vulnerable to COVID-19. In addition, many lower-income, as well as Black and Latino residents, need to physically leave home to work in a frontline job, where the risk of being exposed to the coronavirus is higher.

After real estate agents invented racial covenants in the early 1900s, L.A. led the nation in using them. Their idea of ‘freedom’ shapes the U.S. today.

People living in wealthier areas, by contrast, have had a number of advantages during the pandemic: better access to hospitals, a higher chance of living in uncrowded homes and cleaner air thanks to a lack of nearby freeways (Beverly Hills and South Pasadena memorably fought off construction of freeways through their cities).

Those systemic, structural issues of living in a place close to freeways can quickly result in worse COVID-19 outcomes. For instance, air pollution can worsen asthma symptoms. Black, Latino and Native American residents nationwide are more likely to suffer from asthma, according to the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America. And people suffering from asthma are at higher risk of having severe illness or death from COVID-19, Ferrer said.

Officials say the Omicron variant has flooded the emergency room at Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital, ground zero for hospitals besieged by a winter surge, with people who are not as sick.

Troubling disparities have also been seen in COVID-19 deaths. Between Jan. 23 and Feb. 5, for every 100,000 unvaccinated residents in each racial and ethnic group, 47 Latino residents died, compared with 32 white, 22 Black and 16 Asian American residents.

Among those who are vaccinated and boosted, for every 100,000 people, three Latino and two Black residents died, compared to one each among white and Asian American residents.

There also were stunning COVID-19 disparities based on socioeconomic status and where people lived. From Jan. 29 to Feb. 4, for every 100,000 unvaccinated residents divided into groups by their areas’ poverty status, eight people living in the county’s wealthiest areas died, compared to 76 in the county’s poorest areas.

And even among vaccinated and boosted residents, the disparities remained: For every 100,000 residents, one died in the wealthiest areas, while three died in the poorest areas.

The number of new coronavirus cases reported globally dropped by 16% last week, although some regions are still struggling with large outbreaks.

“It’s clear that living in areas of high poverty is putting people at risk for higher COVID-19–related severe illness and death,” Ferrer said. “Despite the strong protection that vaccines afford, getting vaccinated alone was not an equalizer for people living in areas of high poverty. Where people live and work clearly has a tremendous impact on their risk of exposure, and the availability of health-affirming resources.”

The differing effects of COVID-19 on Black and brown communities, as well as low-income areas, probably helps explain the dynamics on the L.A. County Board of Supervisors, which has been divided over how quickly to lift the indoor mask mandate in the nation’s most populous county.

Of the five supervisors, Hilda Solis and Holly Mitchell — the sole Latina and Black representatives, respectively — have in recent weeks backed efforts to keep the county’s mask mandate in place for a few weeks longer, and have routinely voiced concerns about the disproportionate impact the pandemic has had on their constituents. Solis and Mitchell were elected from districts that have the highest poverty rates and lowest median household income, according to an analysis published by the L.A. County Economic Development Corp. in 2017.

A third supervisor who has backed a slower lifting of mask mandates, Sheila Kuehl, was elected from a district that has a poverty rate and median household income between the wealthiest and poorest districts.

By contrast, Supervisors Kathryn Barger and Janice Hahn were elected from districts with the lowest poverty rates and highest median household income. Both have been vocal about easing mask mandates to be as lenient as the state allows. They say they get many complaints from residents wanting mask mandates to be lifted faster.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.