- Share via

While the pandemic exacted a devastating toll in America’s two largest metropolitan areas, New York City ended up seeing far more COVID-19 deaths per capita than Los Angeles County, a review of data shows.

Health officials and scientists will spend years studying COVID’s spread to divine what fueled the worst global disease outbreak in a century, as well as determine what policies — if any — may have reduced the worst health outcomes.

But as the experiences of New York City and Los Angeles County show, the path of the pandemic was not etched in stone. Numerous factors, and even a bit of luck, ultimately shaped the scale of the COVID crisis.

Officials remain hopeful that California can avoid the significant increases in coronavirus hospitalizations seen on the East Coast.

New York City’s cumulative per capita COVID-19 death rate was about 50% higher than L.A. County’s, data from Johns Hopkins University through early March show.

In raw numbers, New York City — with a population of more than 8.3 million — reported about 45,000 COVID deaths. L.A. County’s death toll was notably lower, about 36,000, even though the region is home to roughly 1.7 million more people.

Put another way: For every 1 million New York City residents, about 5,400 of them died from COVID-19. The comparable figure in L.A. County is about 3,540.

Even when adjusting for the different distribution of ages among the two metros, a similar pattern emerges. A Los Angeles Times analysis of deaths by age group, as reported by local health departments, shows New York City recorded a COVID death rate 40% higher than Los Angeles County’s, with an age-adjusted rate of 4,671 deaths per 1 million residents compared with 3,338.

One factor may be as simple as timing. America’s two largest metros were hardest hit by coronavirus at different points in 2020, with L.A. having longer to prepare.

But other more fundamental characteristics may have left New York City more vulnerable. The Big Apple has a slightly higher proportion of seniors — 16.3% of city residents are age 65 and over, compared with 14.6% in L.A. County — and has colder weather, which keeps people indoors, where transmission risk is higher.

Some experts are cautious about drawing too many conclusions, however.

Differences in death rates, they say, may have more to do with socioeconomic characteristics — such as access to medical care, how many residents live in poverty or overcrowded housing and what percentage of employees can work from home — than pandemic-related health interventions.

“It is is extremely difficult to draw comparisons by one variable — [such as] mask mandate vs. no mask mandate — between different jurisdictions without also controlling for those other factors that are predictive of disease,” said Dr. Jay Varma, director of the Cornell Center for Pandemic Prevention and Response.

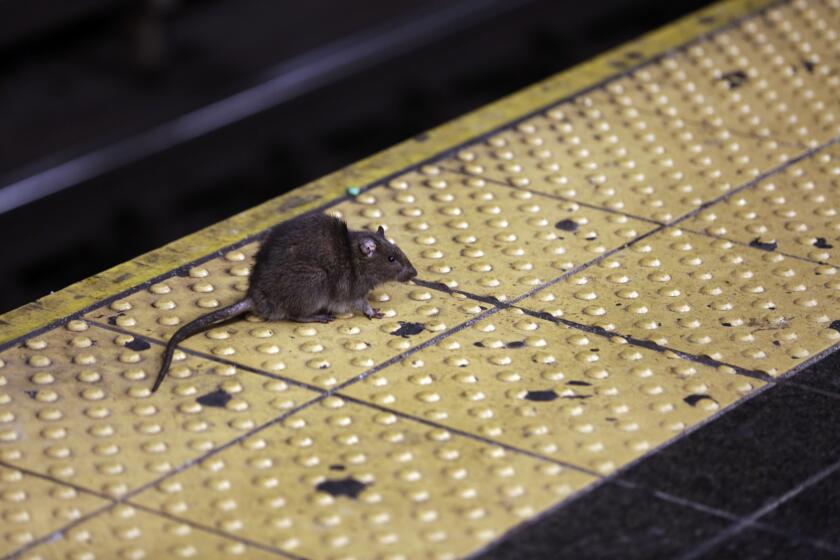

Rats living in New York City’s sewer system can catch the virus that causes COVID-19. Could they incubate new variants and spread them to people?

Some public health leaders, however, haven’t been shy about touting their COVID-19 record and how they measure up to other areas.

San Francisco has been outspoken about its pandemic policies and relatively low death rate — which, according to a Times analysis, is 38% of L.A. County’s and 25% of New York City’s. When adjusted for age, San Francisco’s COVID-19 death rate is one-third of L.A. County’s and about one-quarter of New York City’s.

A number of reasons likely explain the differences between L.A. County and New York City, including the timing of initial stay-at-home orders; vaccination rates, particularly among elderly residents; and the duration of mask mandates. Underlying vulnerabilities in each region also may have played a role.

The initial wave that washed over New York arrived in early 2020, when little was known about COVID and safety supplies were in short supply. Distressing stories from those initial disastrous weeks shocked the nation and were, for many, a wake-up call to the virus’ brutality.

About 22,800 deaths were reported citywide through mid-June of that year. That’s a rate of about 2,700 for every 1 million residents in just a few months.

L.A. County’s death rate during the same time period was one-tenth that, an early degree of success some dubbed the “California miracle.”

That optimism proved premature, however. Los Angeles County reached its most harrowing heights of the pandemic in late 2020 and early 2021, as lockdown-weary residents traveled and gathered for the fall-and-winter holiday season — spawning the region’s own “New York moment.”

Over a six-month period starting in mid-December 2020, L.A. County recorded nearly 1,600 deaths per 1 million residents, about 50% higher than New York City’s rate during the same time period. Los Angeles County was hit particularly hard as the virus stormed through crowded workplaces and poorly ventilated spaces, such as factories and warehouses.

But while that surge was terrible, overwhelming morgues and pushing hospitals to the brink of rationing care, L.A. County health officials may still have benefited from having more time to prepare than New York.

By the next autumn, the roles reversed yet again. As the highly contagious Omicron variant emerged in late 2021, New York City’s cumulative death toll began climbing faster than L.A. County’s — and it has remained consistently higher through the entirety of the COVID era.

Unvaccinated people were more than seven times as likely to die from COVID-19 in Los Angeles County as those who received an updated booster during the latest coronavirus spike.

Vaccination coverage among seniors

Not all experts agree on what could be behind the widely different death rates. But a lagging booster vaccination rate among New York City’s seniors could be one explanation.

Seniors are among the most vulnerable to fall seriously ill and die from COVID-19.

As of Feb. 1, 2022 — the midpoint of the Omicron variant’s first winter — the primary vaccination rate for seniors in L.A. County and New York City was close: 84.5% and 83.8%, respectively, according to a Times analysis of data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But L.A. County got its seniors boosted faster. By that same date, 60.8% of L.A. County seniors had received their first booster shot, compared with 47.5% in New York, the analysis showed.

It’s not clear why booster rates lagged in New York City. Health departments in both jurisdictions say they worked intently to make shots available to seniors.

Even now, there remains a disparity.

As of early May, 45.8% of L.A. County’s seniors had gotten an updated bivalent booster, compared with 32% in New York City, according to the Times analysis of CDC data, the most recent available. Those reformulated shots became available 11 months ago.

Data clearly show that being up-to-date on COVID shots reduces the risk of death. Still, there could be other factors at work.

“We really should look at the proportion of population that’s living in poverty, the proportion of the population that considers themselves underrepresented minorities or people of color; we should look at that situation of density and overcrowding,” L.A. County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said.

“There may be places where we look at New York City, and we would say New York City did a better job than us.”

A long-awaited government intelligence report suggests that COVID didn’t come from a Chinese lab, but don’t expect conspiracy-mongers to be satisfied.

Masking

Following the arrival of the problematic Delta variant in summer 2021, L.A. County was the nation’s first major metro area to renew a universal mask order in indoor public settings — doing so that July.

New York state officials did not re-implement a mask order until six months later, when the initial Omicron wave was well underway.

The efficacy of such mandates, particularly without significant government enforcement, has long been a topic of debate. And in any case, people certainly could have gone maskless in private settings.

But health officials in L.A. County have maintained that heavy-handed enforcement such as fining individual scofflaws wasn’t necessary so long as many adhered to the directive.

Many experts stress that face coverings still protect against the coronavirus and that masking up makes sense — even if it’s no longer mandatory.

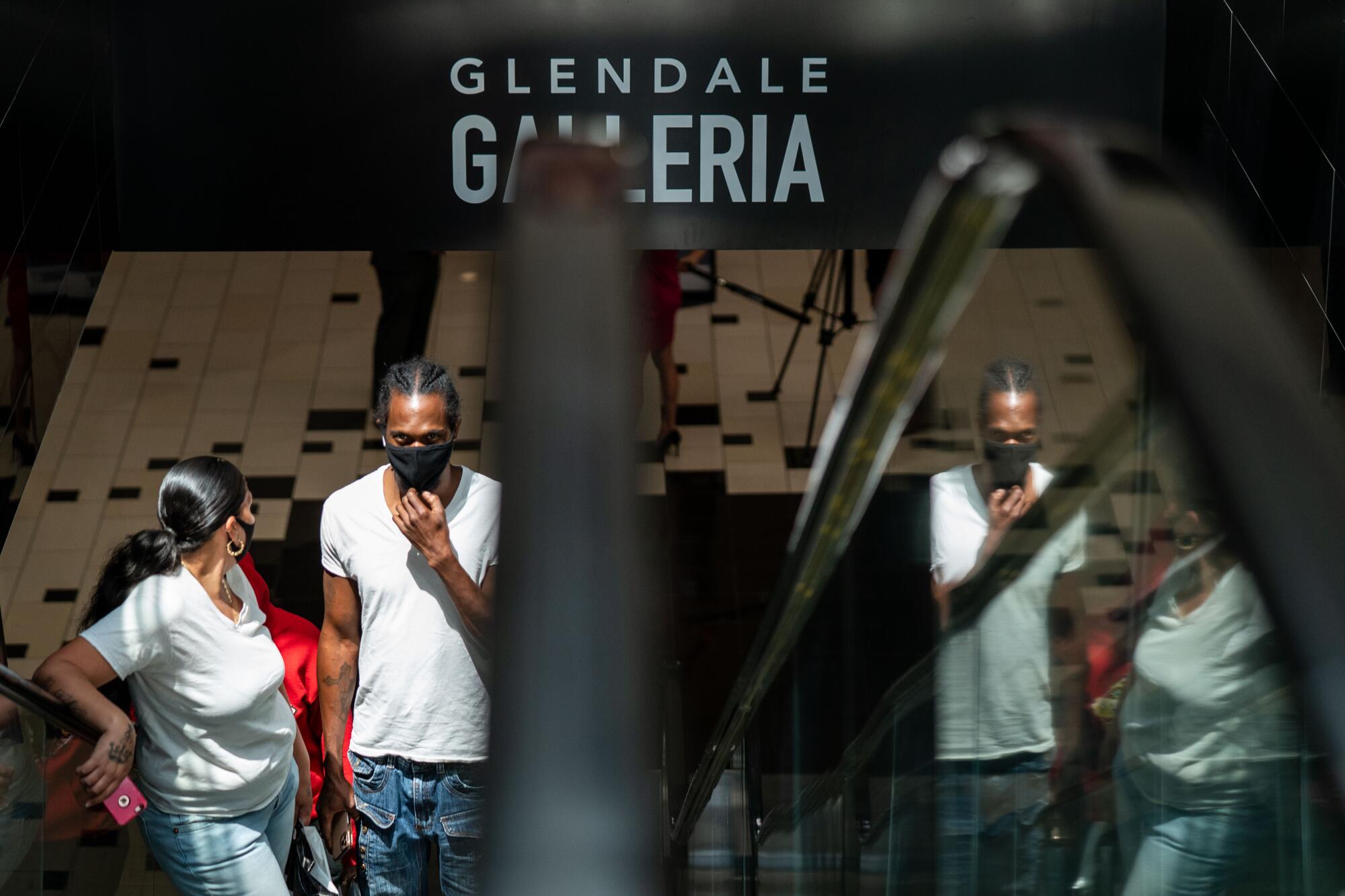

By late 2021, it appeared two masking cultures had emerged. Anecdotally, people who visited both metro areas said the practice appeared far more common in L.A. County than New York City.

Dr. Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, a UC San Francisco epidemiologist, has said that she suspects L.A. County’s earlier mask order influenced people’s behaviors.

While wearing a face covering is still required in certain select settings and still encouraged aboard public transit, the decision for most should now be considered a matter of personal preference.

“When things are not required, there’s a lot of people who do not follow” recommendations, said Dr. Bruce Y. Lee, professor of health policy and management at the City University of New York Graduate School of Public Health and Health Policy. “If you don’t require something, a lot of people are just not going to want to do it.”

While New York and L.A. County had different mask policies in the lead-up to the Omicron era, it’s hard to quantify how that may have ultimately affected COVID deaths.

One analysis comparing state-level pandemic policies, published in the journal the Lancet, suggested state governments’ use of protective mandates was associated with a reduction in their cumulative coronavirus infection rates.

But for death rates, that analysis suggested that it was vaccine coverage that was statistically associated with lower mortality. Other factors that were associated with worse COVID-19 mortality included poverty, lower educational attainment, higher rates of chronic health conditions, limited access to quality healthcare services and lower rates of “interpersonal trust” — trust that people have in one another.

It’s 2023 and you just tested positive for COVID-19. Now what? The latest CDC protocols, isolation recommendations, ways to treat it and ways to prevent long COVID.

Shutdowns

California’s stay-at-home order — the first of its kind in the nation — went into effect March 19, 2020. A similar order, “New York State on Pause,” took effect three days later.

California’s order helped interrupt the virus’ early spread, experts said at the time.

Local health officials in California were also empowered to use their wide-ranging powers at the county level. Gov. Gavin Newsom routinely allowed local leaders to take stricter measures.

But in New York, then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo feuded publicly with former Mayor Bill de Blasio over who should make the final call on a stay-at-home order.

Readers shared a range of experiences, from loss and isolation to new perspectives and stronger bonds.

A bit of luck

It’s possible hard luck played a role in the death disparities too.

While there were assumptions that California — an international travel hub for the Pacific Rim — would be hit earlier than other parts of the country given the coronavirus’ China connections, a different dynamic instead emerged. COVID surges in the U.S. seemed to be influenced more by trends in Europe.

California’s first coronavirus cases — in L.A. and Orange counties — were reported in late January. New York’s wasn’t reported until early March, in a healthcare worker returning from overseas.

L.A. County’s first known coronavirus patient was a then-38-year-old tourist from Wuhan, China, who was passing through Los Angeles International Airport on his way home from a family vacation in Cancun.

The first confirmed case of COVID-19 in Los Angeles was a man from Wuhan, China, who was hospitalized in a secret ward in January and remained the sole patient diagnosed with the virus here for five weeks.

As The Times reported in 2020, the man — the son of a physician long familiar with safety protocols — wore a mask on his international flights, one of the few aboard to do so.

L.A. County officials have said they don’t think the man spread his coronavirus to anyone else, even his wife and preschool-age son, who were traveling with him. It wasn’t until March 2020 that L.A. County reported additional coronavirus cases.

By contrast, the virus was likely spreading widely in New York City by late February. The second confirmed case, a resident of suburban New Rochelle who worked in nearby Manhattan, fell ill in late February, and the area became an early hot spot for COVID-19. The man attended large events before he got sick, according to media reports.

The virus’ rapid spread before the first shutdown orders were imposed could partly explain why New York City’s worst spike came in the early weeks of the pandemic.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.