Op-Ed: How Los Angeles pioneered the residential segregation that helped divide America

- Share via

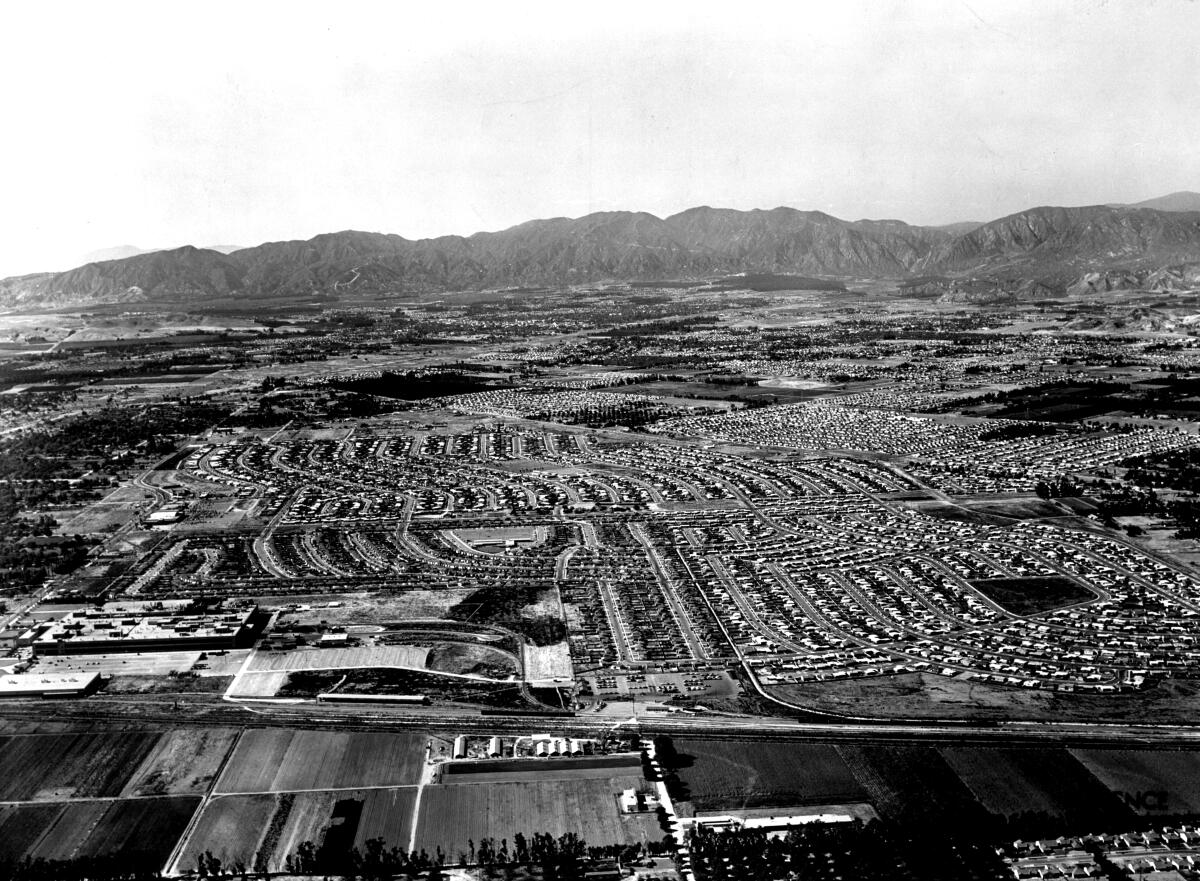

No place has played a more central role in the creation of residential segregation than Los Angeles. With its fast-growing subdivisions and enormous real estate industry, the city shaped the divided neighborhoods and political arguments that drive America today.

The reason has much to do with California. Residential segregation is not natural, normal or historic. It was an early 20th century marketing invention of Realtors, a way to sell homes. Like many American innovations, it flourished first in California.

At the beginning of the 1900s, racially segregated neighborhoods did not exist in American cities. J.B. Loving, a Black real estate agent in Los Angeles, proudly reported in 1904: “The Negroes of this city” have not segregated themselves “into any locality but have scattered and purchased homes” across the best sections. Japanese and Mexican American residents were dispersed in many areas as well.

Where you could live, in L.A. and cities nationally, depended on where you could afford to live — not your ancestry.

By 1917, an African American resident described a very different Los Angeles due to race-restrictive covenants: “We were encircled by invisible walls of steel. The whites surrounded us and made it impossible for us to go beyond these walls.”

Power was at the heart of this change. Newly established all-white real estate boards, including the Los Angeles Realty Board, the largest in the country, organized the industry and came to control the vast majority of home sales. It took a cartel, its members trademarked as “Realtors,” to control whose money could buy a home — to limit America’s free market.

In 1905, pioneering real estate agents in Berkeley and Kansas City, Mo., began recording racial covenants to sell house lots in high-end subdivisions, but L.A. soon became the national leader in using such deed restrictions. Covenants were immediately marketed on luxury developments: The Beverly Crest subdivision was advertised as “permanently restricted … for particular people”; similar language was used for Beverly Hills, Hillhurst Park and Bel-Air.

Middle-class subdivisions quickly followed. Harry Culver, who would become the Realtors’ national president, carved Culver City out of a 200-acre barley field. Twenty blocks south of Exposition Park, a Los Angeles Realty Board vice president established permanent “iron-clad race restrictions.”

Racial restrictions soon filtered down to working-class subdivisions in the region. Eastmont, City Terrace, the St. Francis tract in Highland Park and the new city of Torrance advertised “permanent race restrictions” to benefit “the working man.”

By 1913, racial restrictions were so widespread, the Los Angeles Housing Commission lamented, that Mexican Americans would be able to secure housing only if restrictions “were not placed upon every new tract of land where lots are sold.” Here was a strange new kind of American city.

To ensure such covenants could be enforced, the L.A. Realty Board financed the case that set a national precedent in 1919 when the California Supreme Court ruled that an African American could buy a covenanted home but not live in it.

This decision opened the floodgates. By the early 1920s, when the city’s greatest building boom took off —1,400 subdivisions were added in two years — race restrictions were the norm.

As the country’s fastest growing market, L.A. became the model — not just for restricting individual tracts but whole new suburbs. Realtors conspired with local officials to require covenants on all subdivisions in Glendale so that only one African American owned property there. Ads in the Los Angeles Times in 1925 boasted that “the residents of Eagle Rock are all of the white race.”

Equally devastating for minorities, Realtors began recording covenants on existing homes, too. In Pasadena, where African Americans had lived for generations, real estate agents circulated petitions for race restrictions that went into effect once 75% of owners had signed. This “Covenant Plan” became standard in existing neighborhoods nationwide.

People of color, effectively excluded from 95% of housing, had to pay 20% more for the same quality unit in cities nationally. By the 1920s, the “invisible walls” of America’s racial ghettoes had been firmly established.

“Them: Covenant” on Amazon Prime is a reminder of the all-too-common housing covenants that restricted who could buy homes in certain neighborhoods in Compton, around Southern California and elsewhere. Determined Black people over the decades fought for their rights to live where they pleased.

Thus, in the Depression, when Realtor officials designed the racial policies of the Federal Housing Administration — and helped run the FHA and draw up its then-secret red-lining maps — they institutionalized the racial divisions Realtors had already created.

So in 1948, when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in Shelley vs. Kraemer that court enforcement of racial covenants violated the 14th Amendment, Realtors were threatened as never before. The L.A. Realty Board immediately proposed a constitutional amendment that would overturn the 14th Amendment. It would “assure Negroes of the enjoyment of areas restricted to the occupancy of their race.” This was the same year that South Africa imposed apartheid.

Following their lawyers’ advice, Realtors stopped pursuing the amendment and turned to quieter means to continue segregation. The Supreme Court hadn’t ruled covenants illegal, only that courts would not enforce them. Developers therefore recorded hundreds of thousands of new covenants to threaten any minority buyers, including in the new suburb of Lakewood, which by 1960 had a population of 67,000 — and only seven Black residents.

The most common way Realtors kept neighborhoods all-white was through “racial steering” — lying to minority buyers that a home had just been sold and expelling or freezing out of the business any broker selling to a minority. This was so successful that the San Fernando Valley Fair Housing Council knew of only one Black family able to find a home between 1950 and 1960 in the white neighborhoods that dominated the Valley.

In the mid-20th century, half the Realtors worked in California, and these methods were national norms.

It was thus hardly surprising when civil rights activists — frustrated that segregation had only intensified after the 1948 Supreme Court ruling — pushed for state and local fair housing laws to end such organized discrimination. When California passed the Rumford Fair Housing Act in 1963, banning housing discrimination based on race or ethnicity, Realtors found themselves on the defensive.

The argument the Realtors then devised to perpetuate segregation has driven American politics ever since.

In 1964, at the height of the civil rights movement, Realtors were politically isolated when they asked voters to approve a California constitutional amendment, Proposition 14, to permanently protect residential discrimination. No prominent politician, not even conservatives Barry Goldwater or Ronald Reagan, would support them for fear of seeming racist. To perpetuate discrimination, Realtors designed a new idea of American freedom.

By calling an owner’s right to discriminate “freedom of choice,” and linking it to freedom of conscience and religion, Realtors elevated this single narrow right to an absolute, without regard to the rights of buyers or tenants. Supporting Proposition 14, they assured voters, did not mean you were biased, but that you believed in individual freedom. Realtors had invented colorblind freedom.

White Californians overwhelmingly voted for the Realtors’ proposition in November 1964, on the same ballot that Lyndon Johnson crushed Goldwater in the presidential race. The victory was so sweeping that even after Proposition 14 was ruled unconstitutional, Reagan adopted the Realtors’ message as his own. The Realtors’ use of the libertarian language of individual freedom to maintain social conformity has unified conservatives ever since.

This idea of freedom still shapes America today. When the federal Fair Housing Act finally passed in 1968, it was dramatically weakened by Proposition 14’s shadow. Racial segregation has continued informally but almost as powerfully. Only strong government action could have overcome the Realtors’ legacy of racially exclusive suburbs and organized prejudice. But the popularity of their redefinition of freedom has long prevented such action.

The Realtors’ idea of freedom as a personal right without regard to those of others helped polarize debates over guns and, during the pandemic, has fueled arguments over face masks and vaccinations.

“Freedom of choice,” blazoned by Realtors on L.A. freeway billboards half a century ago, divides America today.

Gene Slater is the author of the forthcoming “Freedom to Discriminate: How Realtors Conspired to Segregate Housing and Divide America.” He is the co-founder and chair of CSG Advisors, which advises public agencies on affordable housing.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.