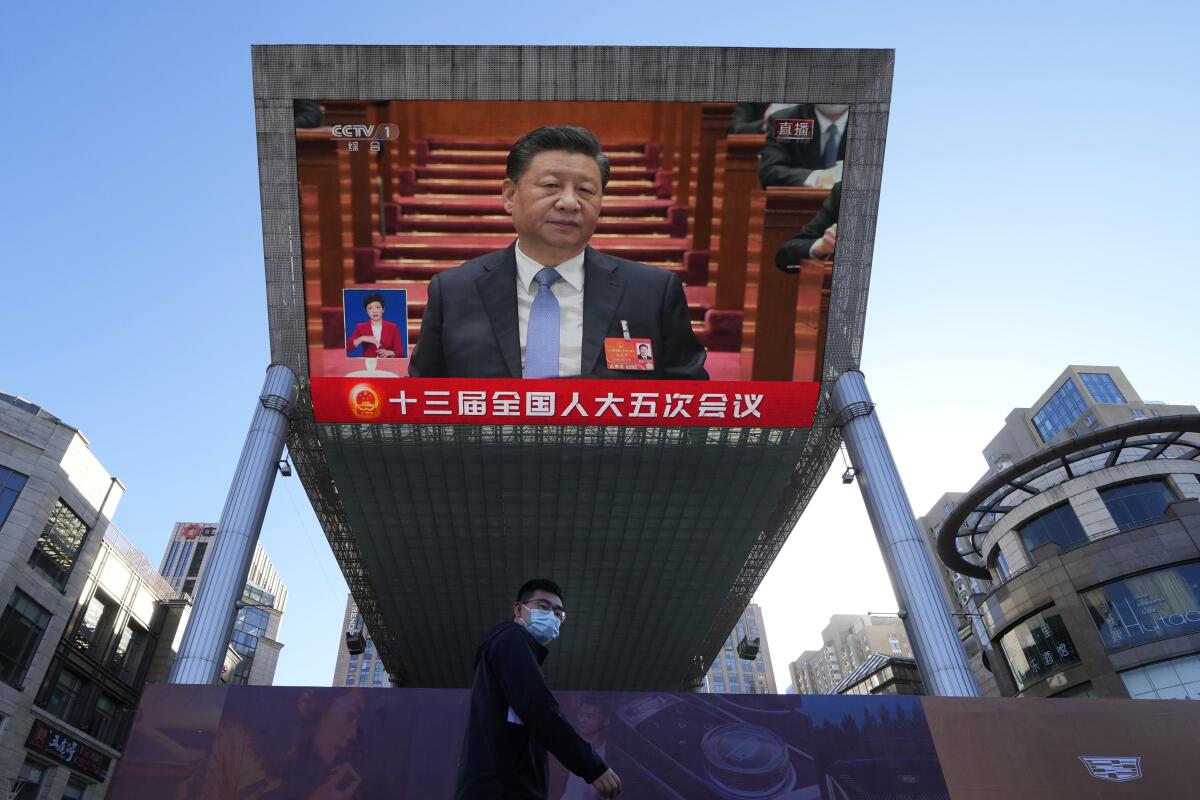

Troubles mount in China ahead of Xi’s bid to stay in power

- Share via

TAIPEI, Taiwan — When Xi Jinping strode into the Bird’s Nest Olympic stadium in the winter, waving and bundled in a black jacket and mask, hundreds of Chinese spectators and performers cheered in what was meant to be the start of a victorious year for their nation’s president.

The Communist Party leader had personally seen to the smooth execution of the Beijing Winter Games, a show of China’s power at a critical moment on the world stage. He had banked on steady, if slower, economic growth. And his firm zero-COVID policy had largely contained a pandemic that had battered the U.S. and Europe.

But things — even amid Xi’s tightly choreographed control of the state — have not gone as planned, presenting a glitch six months before the Communist Party is expected to endorse him for an unprecedented third term as its leader.

A persistent new wave of COVID-19 outbreaks has upended Xi’s zero-tolerance approach, resulting in embarrassing memes and confrontational videos coming out of Shanghai, where 25 million residents have been confined to their homes for over a month. Such harsh lockdowns have derailed manufacturing and consumer spending, deepening worries about a sobering economic slowdown and shaking the confidence of foreign businesses that have long courted opportunities in China.

Meanwhile, Beijing’s support of Moscow in the Ukraine war threatens its already-troubled relations with the West even as it tests Xi’s political partnership with Russian counterpart Vladimir Putin, who relies on China for importing Russian oil. Balancing China’s international ambitions — countering what its president sees as Western hegemony — and its rising domestic concerns is complicating the Xi narrative.

“Before all of this unfolded, I think the party was looking at a much smoother year,” said Alex Payette, chief executive of Cercius Group, a Montreal-based consulting firm that specializes in Chinese politics. “It’s a completely different world now. Xi Jinping needs to be very careful how he handles all of this.”

The political and economic unease comes as Xi prepares to extend his presidency to a third term. In 2018, Chinese lawmakers removed the two-term limit, clearing the way for Xi to cement his status this year as the nation’s most powerful ruler since Mao Zedong.

Over the last decade, Xi has sidelined opponents, silenced dissent and instilled his own brand of Communist Party ideology in law, education and society. He’s built an expansive propaganda and censorship machine that plays on nationalism and party loyalty while stifling critical views, including in Hong Kong, where scores of activists, journalists and protesters have been arrested under a national security law.

Though less a revolutionary than Mao, Xi rules with a similarly firm grip on power. He is essentially a bureaucrat who sees his socialist vision as an embodiment of a new China propelled by a strong military, a solid economy and an assertiveness on global matters. It is unlikely that any crisis will derail his ambitions for a third term. But missteps could still have political consequences, determining how much sway he holds within the party for the next five years.

“His power is at such magnitude over the political bureaucratic system, it’s not a question of whether he takes a third term. It’s a question of how bruised is his agenda by that time,” said Jude Blanchette, who holds the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

In a video address on New Year’s Eve, Xi touted the country’s successes, including combating the pandemic and lifting people out of poverty, adding that China still has more to achieve: “We have set out on a new journey of building a modern socialist country in all respects and are making confident strides on the path toward the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation,” he said.

The 20th National Congress, expected to take place in the fall, is an opportunity for Xi not only to extend his tenure but to promote trusted allies into positions of power. It offers a rare glimpse of who is in and who is out. Any shortcomings in key priorities, such as the government’s handling of COVID, could raise doubts about Xi’s leadership and provide an opportunity to discredit his candidates, analysts said.

“He would still be in pretty powerful control of the system, but he wouldn’t be able to increase the hold and his ability to force these agendas he has,” said Neil Thomas, an analyst with Eurasia Group, which focuses on Chinese politics and foreign policy. “That wouldn’t be a victory for Xi.”

The fate of one Xi loyalist in particular has become a litmus test for how the latest COVID outbreaks will affect his standing. Longtime aide and Shanghai party chief Li Qiang was favored to join the topmost ranks of China’s Politburo Standing Committee later this year. But the city’s chaotic lockdown has spurred some of the most vocal criticism of Xi’s zero-COVID policy yet, casting doubts over Li’s career.

In the last month, Shanghai residents under COVID restrictions have struggled to secure food and medicine, while surging case counts have overwhelmed the city’s medical resources. Some of the public backlash has been directed at local officials such as Li, and Vice Premier Sun Chunlan was sent to Shanghai to oversee management of the outbreak as it spiraled out of control.

“COVID could lead to the delegitimization of some of Xi’s key allies,” said Michael Cunningham, visiting fellow at the Heritage Foundation. “No one wants to be the next Shanghai or the next Li Qiang.”

Although Li has not lost his position, unlike some lower-level Chinese officials, Xi has made it clear that containing the epidemic comes before all else. Shanghai tightened lockdown restrictions this week even amid falling case counts, while Beijing closed off more residential buildings, businesses and subway stations in an attempt to stem local infections.

The stepped-up measures in Shanghai have renewed feelings of anxiety around the city. On social media, people have shared stories and videos of epidemic prevention workers forcing their way into homes for disinfection or taking resisting residents away for quarantine. “Compared with the virus itself, I’m more afraid of home disinfection and one positive case getting a whole floor sent to mass quarantine,” one netizen wrote on Weibo, China’s Twitter-like microblogging platform.

The lockdown intensity has spurred an exodus among expatriates and even some Chinese elite. One Shanghai resident, who asked to remain anonymous, said that leaving the city where she had lived for six years seemed ridiculous before the lockdown. But by the end of April, when she was debating how to ration her last three eggs, she decided to return to Taiwan.

“I’m not afraid of hardship, I’m afraid that it’s not worth anything,” she said. “You can’t really reason with people who execute the government orders.... I don’t know if Shanghai will be the same city anymore.”

But Xi told China’s top leaders last week that the country must adhere to its zero-COVID policy, which he said has proved to be science-based and effective. “We won the battle to defend Wuhan and will surely win the battle to defend Shanghai,” the president said, according to a readout of the meeting.

That dedication means that Xi may have to sacrifice economic growth, another priority before the party congress. In March, Chinese leaders set a 5.5% growth target, a goal economists consider near impossible under current lockdowns, even with abundant government stimulus. With Shanghai and other parts of the country shuttered, manufacturing and consumer spending have plunged, while logistics bottlenecks have chipped away at foreign businesses’ confidence in China.

“China’s economy is the reason that China is a powerful global actor,” Thomas said. “Almost anything is on the table for Xi Jinping to achieve zero-COVID with the growth targets.”

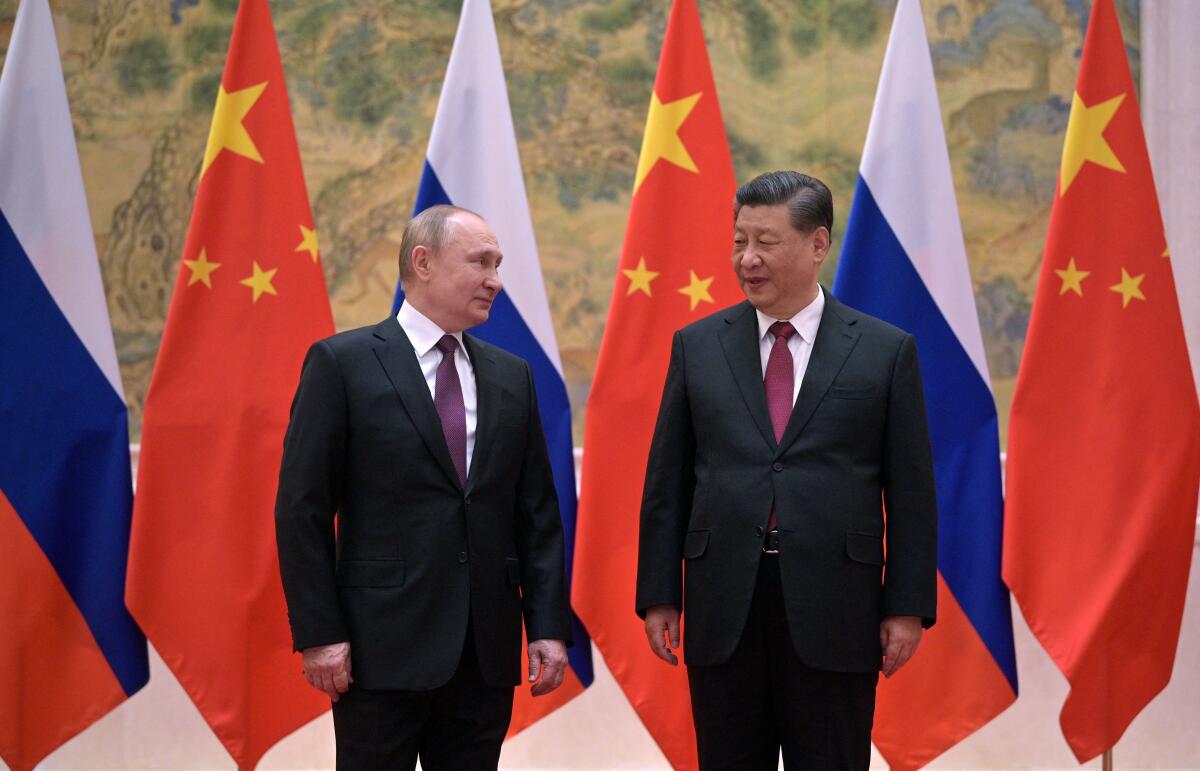

Chinese leaders have also faced increased geopolitical uncertainty, as the war in Ukraine has weakened Russia and brought Western powers closer together. A few weeks before the invasion of Ukraine, China and Russia declared a “no-limits” partnership, emphasizing stronger ties and a united front against a West they see as too expansive and interfering.

It’s unclear how much Xi knew about what Putin was plotting for Ukraine. But the timing of the joint statement increased scrutiny over China’s willingness to support Russia politically and economically, raising concerns about an international backlash. Xi would not want to lose an ally and fellow autocrat like Putin. However, the Kremlin leader’s isolation by the West could foreshadow the treatment Xi might encounter if China were to invade Taiwan in its long-stated goal to bring the democratic island under Beijing’s control.

“China needs Putin to be in power,” said Victor Shih, associate professor at UC San Diego’s School of Global Policy and Strategy. “As Russia suffers greater losses, I think the leaders in Beijing are probably a bit worried.”

Chinese officials have claimed neutrality in the conflict and called for peaceful resolution through diplomatic means. However, state media have echoed Russian propaganda and blamed the conflict on the West. Dissenting opinions have been blocked on the Chinese internet, erasing any sign of doubt or controversy.

Similarly, objections to China’s zero-COVID policy have been censored, including stories of death, suffering and hardship in Shanghai. It is all part of Xi’s domestic and international strategy: scrubbing away voices and inconveniences that question his agenda at a time he needs his authority unquestioned and his reputation intact.

“Ahead of any party congress, the political work of presenting a unified ruling front is crucial,” said Diana Fu, associate professor of political science at the University of Toronto. “On the eve of Xi’s anticipated third term, the chairman cannot afford any appearances of disagreement within its own ranks.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.