Xi Jinping ensures his future with a resolution that rewrites China’s past

- Share via

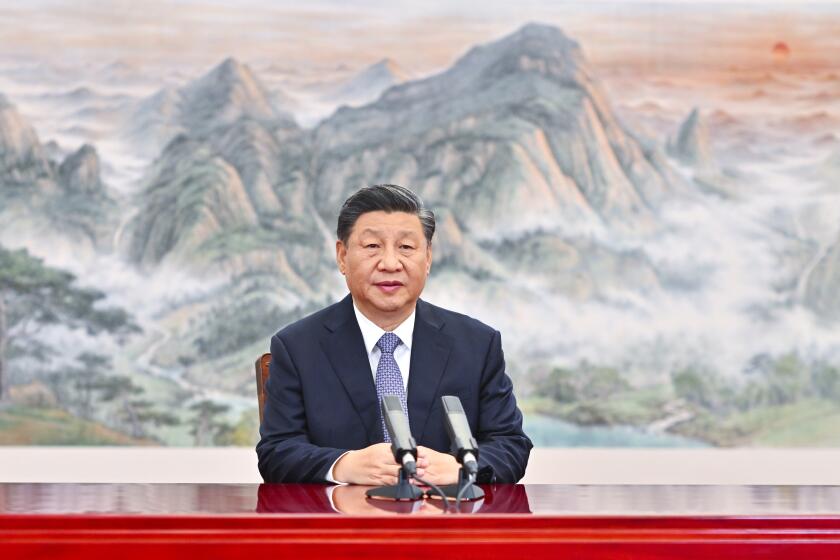

BEIJING — Only two leaders of China’s ruling Communist Party have been powerful enough to rewrite the nation’s history. On Thursday, President Xi Jinping became the third.

His version of Chinese history is simple: The party is great, glorious and always correct. As long as people follow the party, China will rise to inevitable greatness. It stands on the cusp of greatness now, and one leader will soon make that greatness a reality: him.

Such are the contents of a resolution “on major achievements and historical experiences in the party’s hundred years of struggle” passed in Beijing on Thursday by the Communist Party’s Central Committee.

The communique says the Communist Party has “walked through 100 years of glorious history” and “written the most magnificent epic in the Chinese nation’s thousands of years of history.” But the declaration is, crucially, also about the future: It lays the groundwork for Xi to serve an unprecedented third term as president, underlining a political supremacy not seen in China in at least a generation.

“The party’s establishment of Comrade Xi Jinping’s position as the core of the entire party and party center reflects the common wishes of the entire party, military, state and peoples of all ethnicities,” the communique says. “It has decisive meaning for the development of party and state affairs in the new era and the historical progress of the Chinese nation’s great rejuvenation.”

Only two former leaders of the Communist Party, revolutionary founder Mao Zedong and economic reformer Deng Xiaoping, have issued historical resolutions before, in 1945 and 1981, respectively. Both resolutions consolidated the power of a single man who then steered the country through transformational decades.

China’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, sees himself as a savior, anointed to steer the Communist Party and China away from corruption and foreign influence, into a ‘new era’ of prosperity, power and political devotion. Whether his vision matches reality is another question.

Xi’s resolution does the same, analysts say. It underscores his frequent proclamations that China has entered a “new era” of rejuvenation under his rule. Despite a slowing economy and growing tensions with the United States, it’s a statement of confidence and party unity ahead of the 20th party congress next year, when Xi is expected to be given a third term.

“All of this is what we might call ideological Sherpa work, preparing the ground for a big announcement that consolidates Xi Jinping’s position as paramount leader ... and solidifies the party as the driving vehicle of historical destiny for China,” said Rana Mitter, director of the University China Center at Oxford University.

The resolution posits a century’s worth of continuous success, according to the version released in state media Thursday. In contrast to previous resolutions that admitted party errors while affirming overall correct leadership, this one focuses solely on party triumphs.

In the section on the Mao era, when tens of millions died of starvation and violence, the communique praises the party for leading the people in “the broadest and deepest social transformation in Chinese history” and taking a “great leap” toward socialism.

China approves plans to exert more power over Hong Kong, compete with the U.S. in technology and bolster Mandarin-language education.

“Chinese people are not only good at destroying an old world, but also good at building a new world. Only socialism can save China, only socialism can develop China,” it says, with no mention of the famine caused by the Great Leap Forward collectivization campaign or the brutalities of the Cultural Revolution.

Such florid rhetoric is no surprise to anyone who has heard Xi’s previous remarks on history, read the new versions of party history issued this spring or seen the banners, slogans and museum exhibits about “studying party history and following the party forever” on display in every city across China this year.

Still, it is a striking divergence from Deng’s 1981 resolution, which walked a careful line between affirming the ultimate correctness of Communist Party leadership and rejecting the Mao-era mistakes that ravaged the country.

“The big focus in 1981 was to try to make a clear statement about why the party was on the right track now, even though it had made major mistakes,” said Jeff Wasserstrom, a professor of Chinese history at UC Irvine. “This is much more, ‘Let’s focus on how well China’s doing right now.’ … It’s using history in a celebratory tone.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping says tensions in Asia-Pacific must not lead to a return to the ‘confrontation and division of the Cold War era.’

Such framing also simplifies the party’s story to one of “clear-cut heroes and clear-cut villains,” Wasserstrom said. In terms of the latter, “they’re not to be found in the party. They’re to be found in the foreign powers that bullied China during the century of national humiliation and the Japanese and the Americans during the Korean War.”

The party has used history to promote nationalist narratives of united struggle against foreign enemies in recent years, especially as tensions rise between China and numerous countries over trade, technology, human rights, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Xinjiang, Tibet, the South China Sea and other areas.

As many foreign powers respond to China’s military buildup and aggression toward its minorities, neighbors and border regions, the party has cultivated a domestic narrative that the world is against China and wants to “contain” it out of jealousy over its growing strength.

That too is mentioned in the resolution, which says that “major changes unseen in the world in a hundred years” — a euphemism for American decline — have intertwined with the COVID-19 pandemic to create a “more complex and severe external environment.” Domestic economic tasks and coronavirus containment are also “extremely arduous,” the communique says.

Satellite images show China has built mock-ups of a U.S. Navy aircraft carrier and destroyer in its northwestern desert, possibly for military drills.

The party’s answer to such challenges has been to stamp out all dissent and discussion of weaknesses or mistakes, past or present, and to ramp up propaganda and the cult of personality surrounding Xi. Stacks of his books fill front shelves in every bookshop. Posters of his face hang in village homes. His slogans are strung up in every town and city.

A profile of Xi published by the official Xinhua News Agency this week praised him as “a man of determination and action, a man of profound thoughts and feelings, a man who inherited a legacy but dares to innovate, and a man who has forward-looking vision and is committed to working tirelessly.”

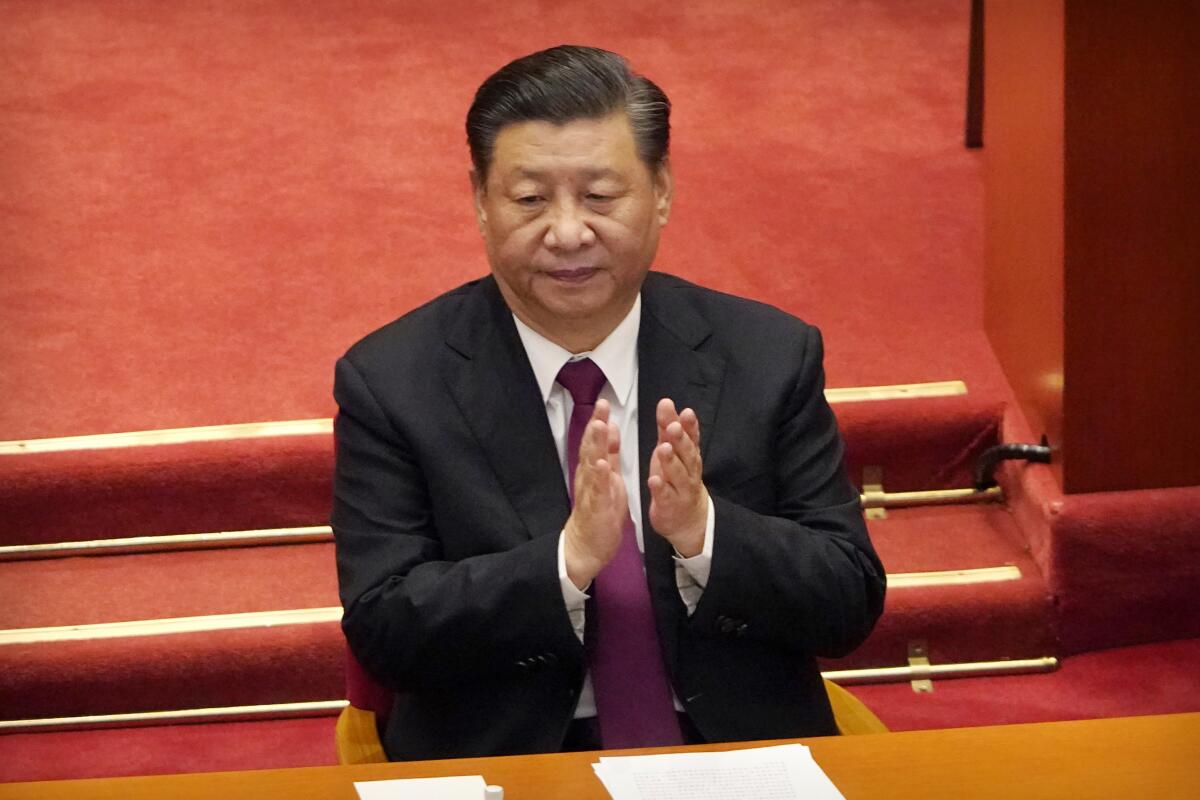

Many observers, including some in China, recoil from this exaltation of a single leader. It is precisely what Deng, mindful of the tumult and violence of the recently ended Cultural Revolution, had tried in the 1980s to prevent by instituting 10-year term limits for Chinese leaders.

“There’s no doubt that Xi Jinping is abrogating many of the fundamental principles that Deng Xiaoping tried to enshrine in the leadership system,” said Orville Schell, director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“He’s basically saying the Deng Xiaoping phase has ended. Our eagerness to reform, our willingness to accommodate foreigners, our more collaborationist attitude toward being in the world — all of that has ended. China is strong enough, and it can act the way great powers of old acted. It can bully other countries and throw its weight around, and it’s either our way or the highway,” Schell said. “This is the new period.”

But the new resolution does not directly repudiate Deng. It praises his economic reforms while ignoring his criticisms of Mao. It ignores all pesky contradictory historical details to project a new message: that all phases of party leadership were correct and necessary because they were led by the party, and are now culminating in today’s age of glory.

“For the Politburo, history is not an academic investigation. It is another form of political language,” said Mitter at Oxford.

There have been times in party history — notably in the early 1980s — when its leaders were willing to admit and examine past mistakes, if only to find a way forward for the nation.

Not so anymore. “Both Xi and the party as a whole have decided that the open debate of different viewpoints on history is ideologically uncomfortable for them,” Mitter said. “At the moment, putting forward an almost entirely uncritical view of history is more useful politically.”

The communique ends with an announcement that the 20th party congress will take place in Beijing late next year. This will be “an extremely important party congress, a major event in the party and nation’s political life,” it says, without specifying why — as if there were any space left for a surprise.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.