China’s paramount leader, Xi Jinping, sees himself as a savior, anointed to steer the Communist Party and China away from corruption and foreign influence, into a ‘new era’ of prosperity, power and political devotion. Whether his vision matches reality is another question.

- Share via

YANAN, China — Stars showered from the ceiling as actors suspended by ropes ran through the air. An unseen man’s voice boomed through the theater: “I have followed this red flag, walking thousands of kilometers with the faith of a Communist Party member in my heart!”

Here in the hallowed ground of northern Shaanxi province, the Chinese Communist Party’s founding myths are on full display. A musical performed twice daily portrays revolutionaries rescuing China from foreign invasion and corruption: Conniving generals coerce Shanghai women dressed like flappers to dance. Communist students are hanged. Trapeze artists in military fatigues flip upside down amid flurries of fake snow.

It is rousing agitprop underscoring a slogan that has saturated the nation in recent years: “Buwang chuxin, laoji shiming” — “Don’t forget our original intentions; hold tightly to the mission.”

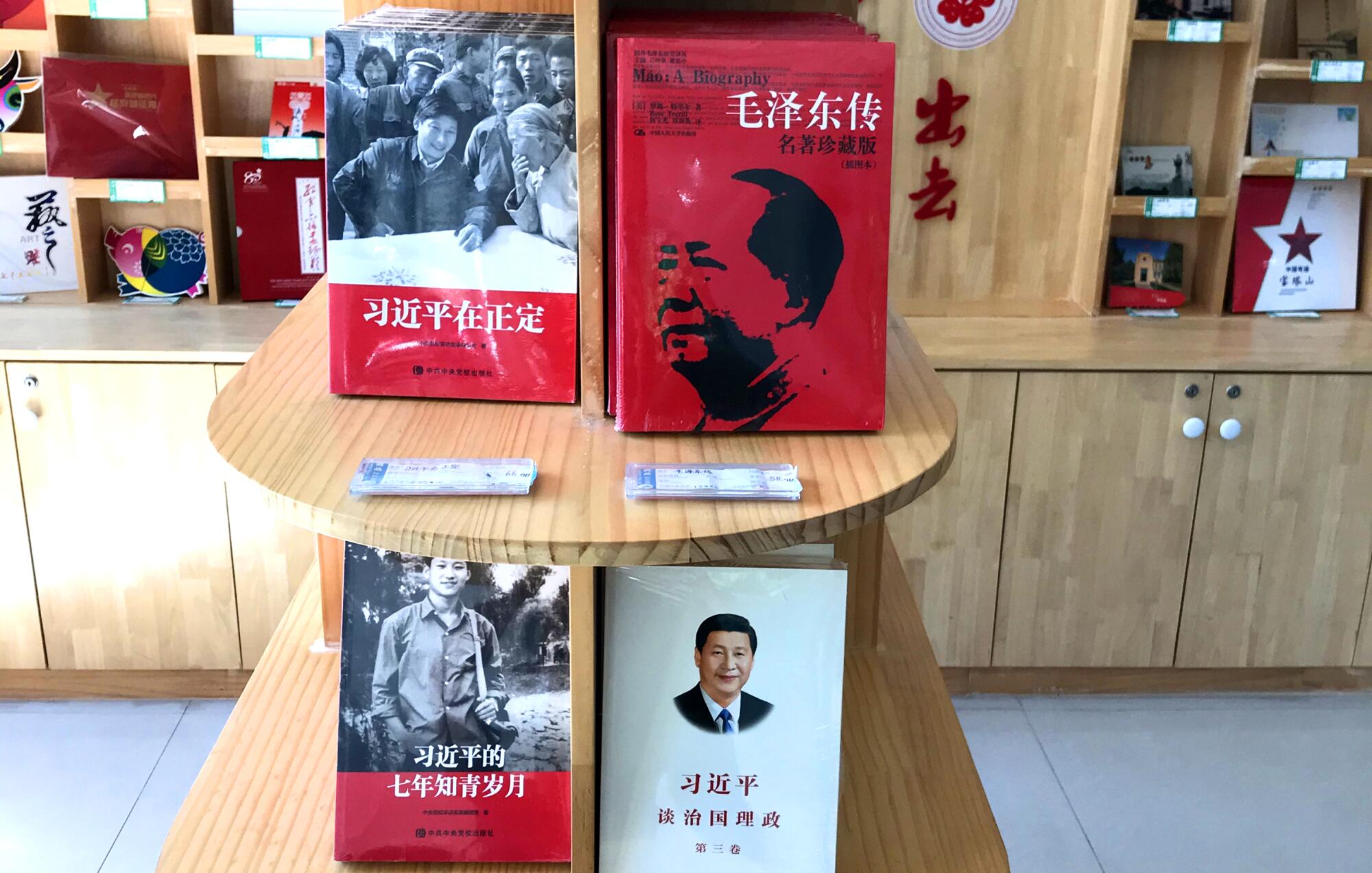

That mission’s changing parameters are key to understanding Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Since coming into power in 2012, Xi has often drawn comparisons to Mao Zedong, the party’s and People’s Republic of China’s founder, a demigod who ravaged the nation in pursuit of communist ideals that led to widespread starvation and arbitrary killing, yet commanded adoration from the masses.

No Chinese leader since has held as much authority — until Xi. But he is not Mao 2.0. A disciplinarian, not a revolutionary, Xi is driven by a need for control. He is a legalist in the tradition of Han Feizi, the philosopher who taught China’s first emperor, Qin Shi Huang, that people are fickle and selfish and must be kept in line through law and punishment. An ethnic nationalist, Xi holds a vision of Chinese revival that draws on allusions to past empires. He speaks in Marxist terms of class struggle and uses Maoist tactics such as self-criticism and rectification, but his brand of communism also promotes Confucius and e-commerce.

The Chinese president sees himself as a savior, anointed to lead the country into a “new era” of greatness propelled by rising prosperity and political devotion. Whether his vision matches reality is another question.

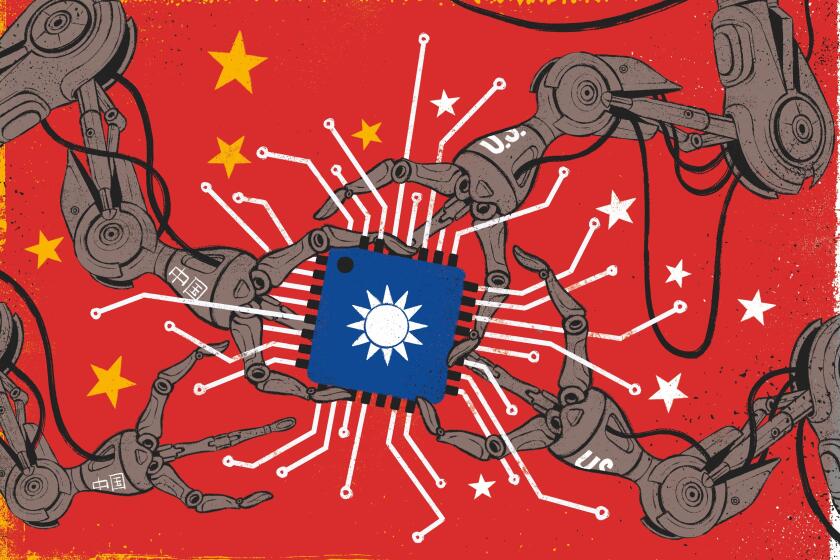

The stakes of achieving Xi’s grand plan are high. His rule has led to sweeping crackdowns on corruption and political dissent at home and an increasingly assertive foreign policy, including provocative naval exercises in the South China Sea and Beijing’s tense relations with Washington over trade, spying, technology, and repression of pro-democracy movements in Hong Kong.

To appreciate Xi’s grip on the country, one need only look at the coronavirus — China stumbled early with the Wuhan outbreak, but quickly recovered through strict lockdowns, contact tracing and mass testing. It has virtually stemmed the disease while racing to become the first nation with a publicly available vaccine. China’s economy grew nearly 5% in the third quarter while the United States and Europe continued to struggle with COVID-19. Xi and the party point to such signs as proof of the Chinese system‘s superiority.

Meanwhile, far from party headquarters in Beijing, an origin story is tended in a village of yellow hills.

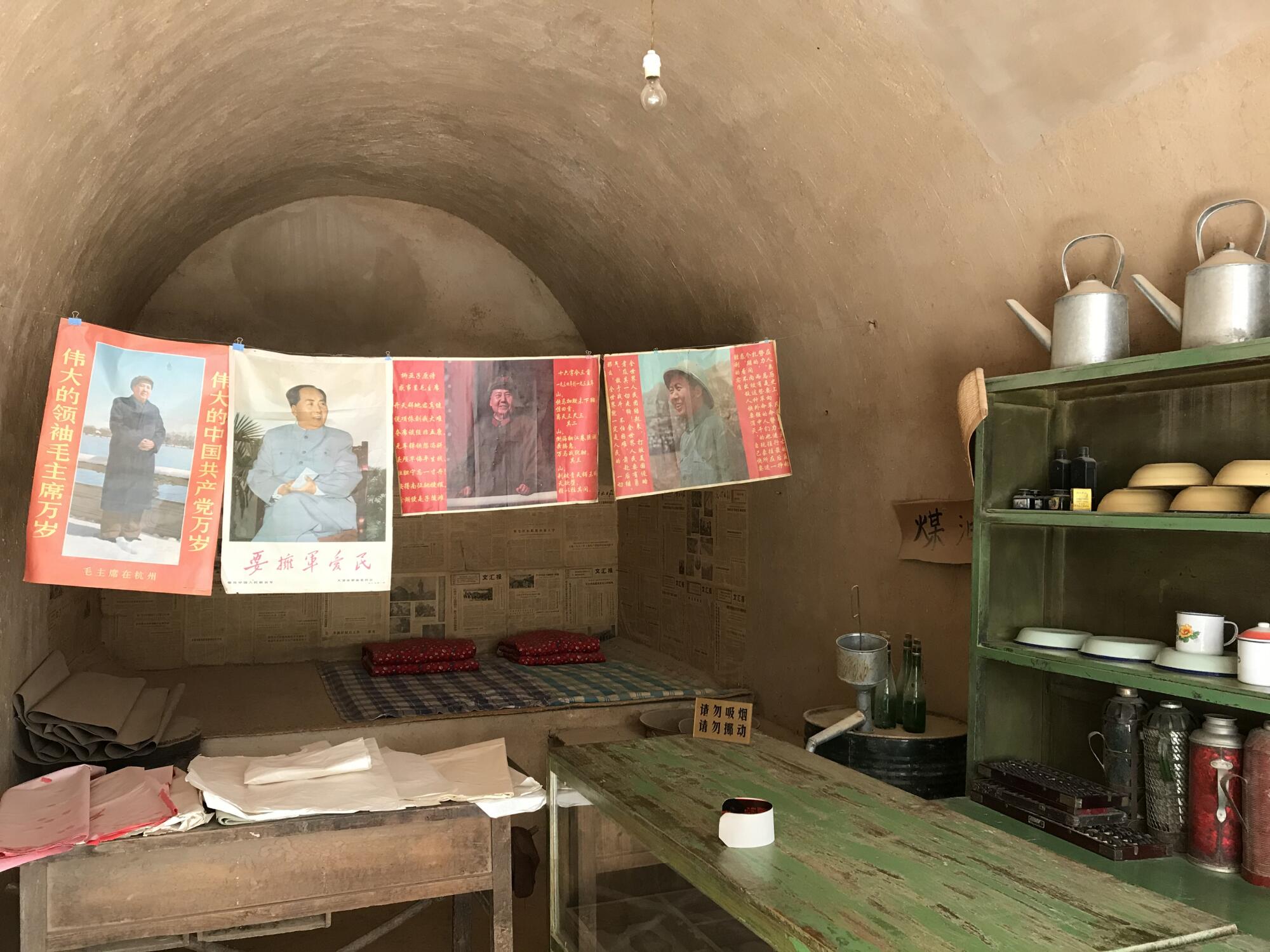

Two hours away from the theater in Yanan, tourists in matching red scarves visited a set of caves in Liangjiahe, where Xi spent seven years during the Cultural Revolution. He was one of millions of city youths “sent down” to work in rural areas in the 1960s, officially to “learn from the peasants” but also to reduce urban unemployment and quiet the violence of radical student groups.

“Here is where the chairman ate coarse grain buns with the farmers,” a guide said as a group of teachers from Guangzhou peered inside one of the caves. Newspaper cutouts with headlines about Mao and a photo of teenage Xi, slightly smiling into the distance, hung above rolled-up blankets and a straw mat on a raised mud platform. A bag of anti-flea powder sat prominently displayed on the window ledge, a testament to the fleabites young Xi endured.

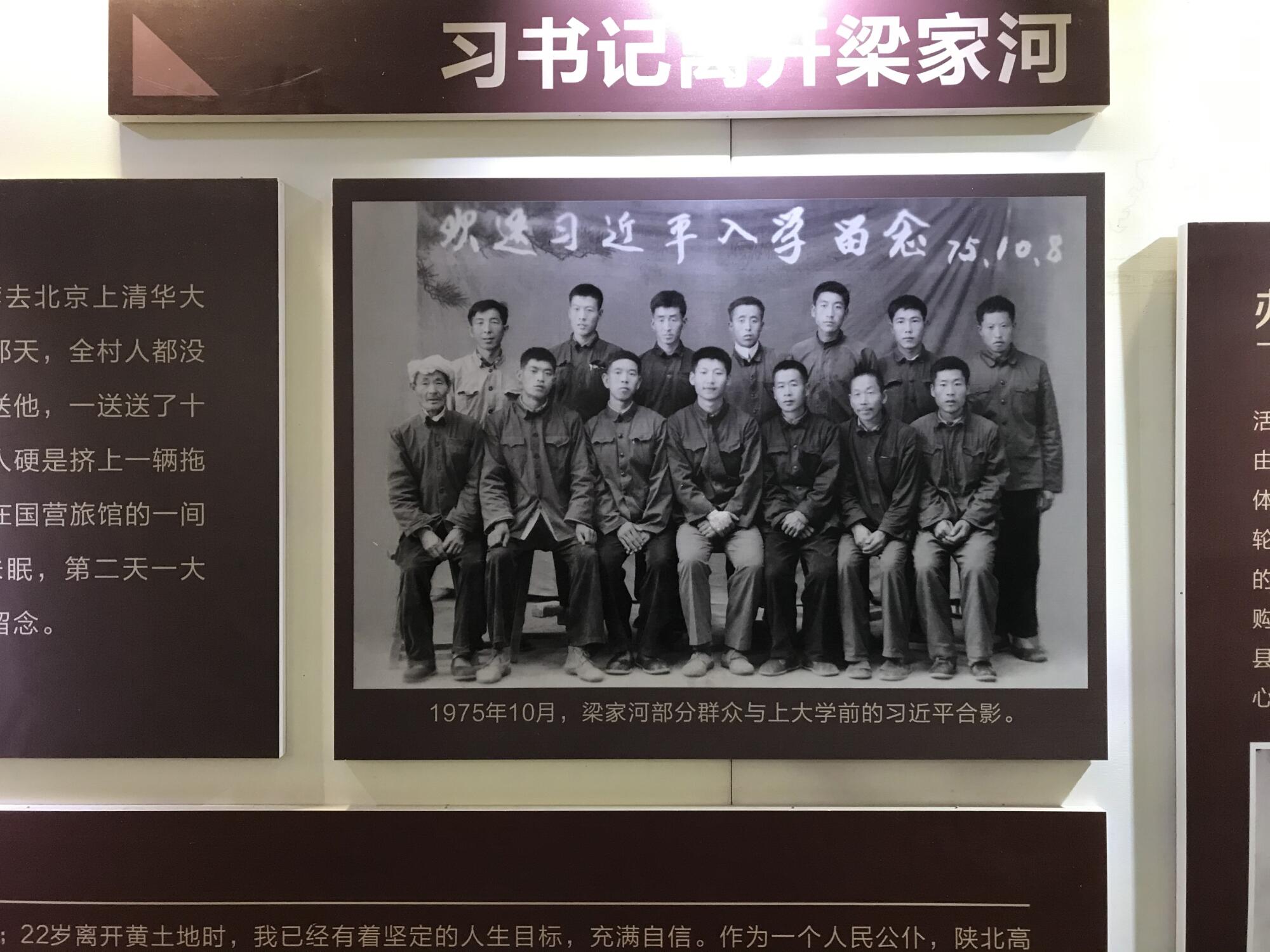

A small museum weaves Xi’s narrative with that of the Communist Party’s benevolence, explaining that Xi read stories and dug wells for the villagers as a teenager, then charting the village’s recent rise in average income per person — from $25 a year in 1984 to $3,218 a year in 2019.

When Xi speaks about his coming of age, he points to Liangjiahe. “Northern Shaanxi gave me a belief. You could say it set the path for the rest of my life,” Xi said in a 2004 interview with the People’s Daily.

He started out lazy and weak in the village, but by the end of seven years, he had experienced hard labor and developed a taste for the pickled vegetables of peasants. It is a folklore reminiscent of Mao’s claims of seeking liberation for the oppressed underclass. But whereas Mao incited grass-roots movements and armed struggle, Xi’s approach to power eschews mass mobilization.

“You see this huge emphasis on order and discipline. That’s seemingly a very strong reaction against the excesses of the Cultural Revolution and Mao’s chaotic approach,” said Ryan Mitchell, a professor of law at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. Under Mao, the legal system was “decimated,” he said. “Xi is instead trying to institutionalize things, including his own power.”

The seeds of Xi’s resolve and ruling style are in his upbringing. When the Cultural Revolution began in 1966, his father, Xi Zhongxun, a founding revolutionary who joined the party while in jail at age 14 for trying to poison his “reactionary” schoolteacher, had already fallen into disgrace.

Xi Zhongxun lived through hellish periods of internal party factionalism. He was purged multiple times — removed from power, incarcerated, even threatened with being buried alive — for his association with individuals and “gangs” who were deemed disloyal. Some of his mentors and associates died by suicide. Yet he remained devoted, even proud of his suffering at the party’s hands.

“It’s hard to think of someone who’d more fanatically put party interests above his own interest,” said Joseph Torigian, a professor of history and politics at American University who is writing a biography of Xi Zhongxun. “A lot of that generation took pride in how much they were able to suffer without losing faith in the party. They often wrote about it as a sort of forging process.”

At home, Xi Zhongxun — who went from vice premier at one point to working at a tractor factory when he was purged — was a “brutal disciplinarian” who struggled with depression, Torigian said, according to memoirs, unpublished diaries and interviews with friends of the family. When Xi Jinping was a child, he likely saw his father sometimes crying, screaming and hitting people, sitting in a room with all the lights off, and lashing out at his wife.

The family’s humiliation and persecution led one of Xi’s stepsisters to kill herself. Xi Jinping was locked up several times because of his father’s position and had to denounce him in public, he said in a 1992 interview with the Washington Post: “‘Even if you don’t understand, you are forced to understand,’ he said with a trace of bitterness. ‘It makes you mature earlier.’”

At the same time, Xi’s peers, other “princeling” children of high-ranking Chinese Communist Party leaders whose parents hadn’t been purged, were rampaging through Beijing as Red Guards, given power to torture and often kill teachers, intellectuals and authority figures. They believed they were bringing about utopia. Xi was not allowed to join them, even as he saw himself as a true party disciple.

Some scholars suggest that the shame of that period pushed Xi not to question or renounce the extremities of Mao’s leadership, but to prove himself worthy to lead.

“He sees himself as the legitimate successor of the CCP red dynasty by blood,” said Yinghong Cheng, a professor of history at Delaware State University. Many princelings of Xi’s generation regard state power as their “family inheritance,” Cheng said. “They are entitled to it, must hold it firm, and losing it means losing everything.”

Everything I’d built on — Marx, Lenin, Mao — they were all wrong. I needed to adjust from the roots, to spit out that wolf’s milk we had all drunk.

— A prominent Chinese historian

Most of Xi’s generation were idealists when they were young, said a prominent Chinese historian who also spent years as a “sent-down youth” and asked not to use his name for protection. But for him and many liberal intellectuals, returning to university in 1977, after Mao died and the Cultural Revolution ended, sparked a painstaking reassessment.

“Everything I’d built on — Marx, Lenin, Mao — they were all wrong. I needed to adjust from the roots, to spit out that wolf’s milk we had all drunk,” the historian said. “Inch by inch, you rebuild your worldview. It takes decades to become cleareyed, to say, ‘Where did we go wrong? What is China? Who are we?’”

Xi did not go through that process, the historian said. He left Liangjiahe for Tsinghua University in 1975 as a “worker-peasant-soldier” student, one of the children with “red” class backgrounds who were nominated to return to school during the Cultural Revolution by their work teams. Chosen for their good performance in Mao’s system, many such students “strengthened their own red identity” rather than deconstructing it, the historian said.

After his father was rehabilitated in 1978, Xi Jinping worked as a party official in several coastal provinces. It was there he saw firsthand how market reforms brought wealth and rising living standards — but also an explosion of corruption. The experience would stay with him. In 2012, shortly after Xi came to power, he went on a “southern tour” to Shenzhen, retracing the footsteps of Deng Xiaoping, who in the 1970s and ‘80s oversaw China’s economic opening.

But Xi’s vision of reform was different. In his view, China’s Communist Party was in crisis: Inequality and corruption were rampant and people had abandoned their ideals. The nation risked repeating the fate of the Soviet Union, he said in a 2012 speech, where “no one was man enough” to assert ideological control and resist “Western ideas” like democracy, separation of powers or rule of law. China needed a strong “man” to reassert the party’s power and inspire the masses.

Since 2012, after a steady rise through the party from being a secretary in the Central Military Commission to a member of the Politburo Standing Committee and then its paramount leader, Xi has been that man. He targeted corruption, taking on officials as powerful as Zhou Yongkang, the former head of China’s security apparatus. He restructured the military, media and legal-disciplinary institutions to assert stronger party control. He did away with term limits — in effect making himself leader for life — and enshrined “Xi Jinping Thought” in the Constitution, rendering himself indivisible from a party that permeates every aspect of Chinese society.

Xi’s ambitions abroad have been just as grand. He has expanded China’s global power through multibillion-dollar development projects like the Belt and Road Initiative and by gaining more influence in institutions like the United Nations. He has capitalized on a United States that has turned isolationist under President Trump, dispatching China’s corporations, diplomats and spies everywhere from Nairobi, Kenya, to Brussels in what is becoming a new world order.

Xi often says that this era is one of “great change unseen in a hundred years,” namely that the world’s top superpower is in decline, and that this is China’s moment to rise. “Systemic advantages are a nation’s greatest advantages, and systemic competition is the most fundamental competition between nations,” Xi was recently quoted saying in the People’s Daily.

That determination to prove the Chinese system superior has driven impressive moves toward combating poverty and pollution, making this nation of 1.4 billion people a dominant force in high-tech industries and allowing it to contain the coronavirus outbreak — even as much of the world blames China for allowing the disease to spread.

But Xi has also stifled all perceived threats to social “stability”: not only dissidents, but also human rights lawyers, labor activists, poets, feminists and more. He has launched “Sinicization” programs targeting religious and ethnic minorities, including the mass incarceration of Uighurs and other Muslims. He has imposed a new national security law that is smothering the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong. He has tightened control over schools from kindergarten through university, reinforcing “patriotic education” with Xi Jinping Thought as a guiding ideology.

In July, he announced a new “education and rectification” campaign to discipline China’s political and legal systems, including police officers, judges and members of the secretive Ministry of State Security. The campaign slogans call for “turning the knife inward” to “scrape poison off the bone,” meaning to find, punish and reform — or purge — any potentially disloyal individuals.

He has turned 90 million party members into slaves, tools to be used for his personal advantage.

— Cai Xia, granddaughter of a revolutionary leader

Officials leading the campaign have called it a renewed version of the rectification drive Mao launched at the party base of Yanan in the 1940s, where the chairman used group indoctrination, self-criticism, forced confession and “struggle” sessions to eliminate perceived internal rivals.

It is unusual that Xi “does not perceive his power to be completely consolidated, even eight years in,” said Sheena Greitens, a professor of public affairs who studies Chinese approaches to security at the University of Texas at Austin. Xi may be launching this campaign to prepare for 2022, when he will transition into an unprecedented third term, she said.

But a political system prone to crackdowns can turn suspicious and brittle, with everyone afraid to point out problems or admit mistakes. It is what allowed the initial cover-up of a virus spreading in Wuhan last winter, at the cost of thousands of civilian deaths. When things go wrong, however, Xi has used a classic technique: punishing local officials while keeping the emperor free of blame.

Perhaps the trickiest part of his reign is Xi’s attempts to combine market reforms with state leadership. China’s economy — despite its rebounding from the coronavirus — has slowed dramatically under Xi, in part because the private sector has been spooked by his talk of communist revival. The U.S.-China trade war, a drive for “decoupling” the two economies and the pandemic’s impact have also strengthened Xi’s support for state-owned enterprises, which he calls the core of China’s economy despite their inefficiencies.

He has made high-profile speeches reassuring China’s private companies, like tech giants Huawei and Alibaba, that they are crucial to the China dream — but also demanded that they “listen to the party, walk with the party,” and strengthen internal party committees’ role in companies’ decision-making.

Xi’s militant nationalism has also provoked backlash. The Chinese military has carried out aggressive maneuvers in the South China Sea and rattled Taiwan by sending fighter planes into its airspace. Chinese troops have had deadly clashes in recent months with Indian soldiers along a disputed border. Xi’s reorganized security forces have increased arbitrary detention of foreigners including citizens of the U.S., Canada, Australia, Taiwan, Japan, Hong Kong, Belize, Turkey and Kazakhstan.

A recent Pew Research Center survey found that unfavorable views of China have reached historical highs in 14 advanced world economies, with a median of 78% of respondents saying they have “no confidence” in Xi’s handling of world affairs — though the ratings on Trump are even worse.

Ironically, a popular nickname for Xi on the Chinese internet is the “accelerator in chief,” meaning that his aggressive approach to “stability” has caused more domestic and international conflict and is speeding his government toward self-demise. Criticism has risen even from fellow princelings: Cai Xia, the granddaughter of a revolutionary leader who taught at the central party school for four decades, was recorded calling Xi a “mafia boss” this year.

“He has turned 90 million party members into slaves, tools to be used for his personal advantage,” Cai said.

Ren Zhiqiang, a real estate tycoon who fell from the red elite, called Xi “a clown stripped naked” in a critique of Xi’s COVID-19 response this year. “The reality shown by this epidemic is that the party defends its own interests, the government officials defend their own interests, and the monarch only defends the status and interests of the core,” Ren said.

Ren and Cai have been expelled from the party. Cai is now in the United States. Ren has been sentenced to prison for 18 years.

The rising ire of elites and foreign powers is, in Xi’s view, a necessary part of China’s struggle on its socialist path. The intellectuals may be alarmed, but not the masses. A recent Harvard Kennedy School study of Chinese public opinion from 2003 to 2016 found that satisfaction with the government had risen, especially among the rural poor in inland regions, who received more targeted social assistance during the survey years.

“This fits exactly with his self-understanding: ‘I’m here for the people, and that’s why I’m against you capitalists, corrupt elites and intellectuals,’” the historian said. “He thinks he is saving this party.”

Whether the people see Xi that way, however, is harder to tell. In Liangjiahe, two women carrying umbrellas followed a Times reporter everywhere she went. When two villagers, a man in his 60s and a woman surnamed Ma selling souvenirs and mooncakes, began telling the reporter that they were struggling economically, the two women approached and glared at the villagers, who stopped speaking.

“Life is hard, but they won’t let us talk about it,” Ma said under her breath as the women, who said they were also locals, approached.

Ma gave the reporter her phone number, but when the Times called later, she said only: “We don’t have any problems. We are very happy. We are thankful to the government.”

“Don’t come to the village. We wouldn’t dare speak to you even if you did,” she added, and hung up.

This is the third in a series of occasional articles about the effect China’s global power is having on nations and people’s lives.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.