Coronavirus Today: It’s everywhere

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, June 28. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

Just a couple of weeks ago, I wondered whether the coronavirus would take a summer vacation. Now we know the answer: It most certainly will not.

It feels like people with COVID-19 are everywhere. Last week I marveled that the coronavirus found its way to Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has arguably done more than any other American over the last 2½ years to keep the virus at bay. (During a virtual public appearance at a White House briefing, he said he’d been feeling “quite fine” since he tested positive on June 15 and credited the vaccines, boosters and antivirals he helped bring about as director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.)

He’s hardly the only high-profile person to get COVID-19 this month. Xavier Becerra, the U.S. secretary of Health and Human Services, got sick while visiting California, less a month after he got sick in Germany. His fellow Cabinet secretary Pete Buttigieg caught COVID-19 too. The governors of Pennsylvania, Arizona, North Carolina and Nebraska all announced mild cases. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau became a two-time infectee, while Sen. Roger Wicker of Mississippi got it for the third time.

Rolling Stones frontman Mick Jagger came down with COVID-19 while on tour in Europe. So did two members of Ringo Starr’s band, forcing the cancellation of 12 shows. An outbreak on the set of the Amazon Studios series “Expats” caused the production, which stars Nicole Kidman, to wrap early.

It’s not just the headlines that make COVID-19 seem ubiquitous. It’s going around our virtual office, sickening people who managed to remain virus-free during the pre-vaccine era and through winter surges. The same thing is happening where my husband works. I don’t think we’re unusual in this regard.

Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, an infectious-diseases expert at UC San Francisco, wouldn’t think so either.

“It’s going to get easier and easier to get and harder to escape infection,” he told my colleague Luke Money.

There’s a reason it feels like the coronavirus has gained momentum — it has.

It took about 22 months for California to record its first 5 million official coronavirus infections. The state has racked up just about as many cases in the seven months since Omicron was first detected here. (The statewide case count crossed the 10 million mark on Tuesday, according to the Times’ tracker.)

Columnist Robin Abcarian was one of them. She came down with her first case of COVID-19 a couple of weeks ago. She thinks she caught it from her 12-year-old niece, who probably became infected in the last day or two of the school year.

“I woke up with a sore throat, slight fever and the sinking feeling that my luck had run out,” Abcarian wrote. “Two red lines on the rapid antigen test confirmed it.”

After avoiding the coronavirus for so long, she had started to feel invincible. She stopped wearing a mask and became less vigilant about washing her hands.

“I let my guard down,” she admitted. That’s all it took.

Thanks to Omicron and its many subvariants, there’s hardly a family, friend group or other social circle that the coronavirus hasn’t touched. The pace of new infections makes it feel like if it hasn’t gotten you yet, it’s just a matter of time.

“But that doesn’t mean we put ourselves in a sort of mindset that, ‘You know, to hell with it. I’m just going to do anything I want to do anyway,’” Chin-Hong said.

Resistance isn’t necessarily futile, he and others say. Chin-Hong hasn’t gotten it. Neither has Dr. Robert Wachter, chair of UC San Francisco’s Department of Medicine.

“I don’t buy the inevitability argument,” Wachter told Money. He credits vaccines and boosters, along with a willingness to take sensible precautions.

“On the other hand,” he said, “there are plenty of people who I know who have been just as careful as I have and have gotten it in the past few months, so I think there’s some randomness to this.”

The subvariant known as BA.2.12.1, which ignited the wave that began in April, is still dominant in the U.S., accounting for an estimated 42% of infections, according to the most recent estimate from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. But two other subvariants, BA.4 and especially BA.5, are gaining ground. They’re now thought to be responsible for a combined 52% of coronavirus cases in the U.S.

That helps explain why so many people are getting repeat infections these days. Both BA.4 and BA.5 are adept at overcoming the immunity gained from previous Omicron infections.

So far, hospitalizations have remained manageable despite the fact that the state’s current surge includes the third-highest peak of the entire pandemic. But that hasn’t been the case everywhere. The World Health Organization’s latest weekly update notes that “the rise in prevalence of BA.4 and BA.5 has coincided with a rise in cases” in several regions, and, in some countries, that increase “has also led to a surge in hospitalizations and ICU admissions.”

Dr. Robert Kim-Farley, an epidemiologist and infectious-diseases expert with UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health, warns that “it will be difficult for many to avoid being exposed to COVID-19 going forward.”

But just because you’re exposed to the virus doesn’t mean you’re bound to get it. You can reduce your risk by staying up to date with your vaccinations and booster shots, and by wearing a mask in crowded places, especially indoors.

“Everyone needs to be vigilant to avoid exposure and prevent severe disease,” he said.

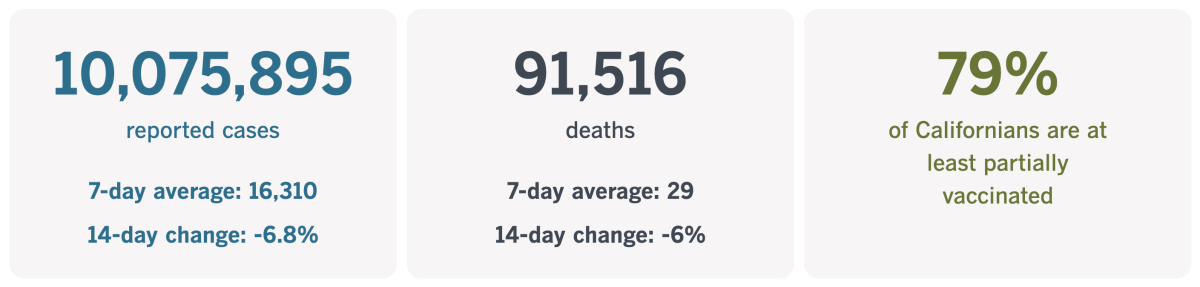

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 5:08 p.m. Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

The politics of health

Sometimes it’s hard to think of anything in American life that isn’t politicized. The cars we drive (gas guzzler or electric vehicle?), the foods we eat (red meat or kale?), the sports leagues we follow (NASCAR or the NBA?) — all of it seems to signal whether we’re on Team Red or Team Blue.

When it became clear that the coronavirus outbreak would balloon into a full-blown pandemic, it could have been a time for the country to pull together against a common threat. Spoiler alert: That didn’t happen.

Straightforward public health measures that are not inherently political — most notably, wearing a face mask to prevent infectious germs from spreading — became hyperpartisan statements. Instead of joining forces to flatten the curve, the country fought with itself. I’ll never forget the reader who called me a liar for making the factual statement that the more people wear masks (she called them “face diapers”) while around others, the less the coronavirus will spread.

When the first COVID-19 vaccines came along, I thought things might change. The vaccines were produced in record time thanks to former President Trump’s multibillion-dollar investment in Operation Warp Speed. He and his supporters could have taken credit for the achievement and touted the shots. Instead, they’ve been more likely to reject them.

In fact, the partisan vaccination gap has been widening over time, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation. A year ago, the overall vaccination rate in U.S. counties that voted for President Biden was almost 9 percentage points higher than it was in counties that voted for Trump. By the end of 2021, that gap had widened to about 12 percentage points and stood at 13 in January.

The Biden administration attempted to boost vaccination rates everywhere by implementing mandates. The most contested of these would have required most workers in companies with at least 100 employees to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 or else be tested for a coronavirus infection once a week. Attorneys for some Republican states challenged the administration’s authority to implement the mandate, and the U.S. Supreme Court sided with them.

Throughout the pandemic, the high court has misinterpreted or set aside science as it has weighed the legality and constitutionality of public health measures. Dr. M. Gregg Bloche, who has both medical and law degrees from Yale and teaches health law and policy at Georgetown, pointed out one glaring example in an essay published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine.

When it became clear that the coronavirus spreads from person to person via airborne particles, some local authorities set limits on the number of people who could congregate indoors for an extended period of time. The rules made crowded indoor church services (along with other types of gatherings) off-limits, while activities that required only a quick dash inside were still OK.

The justices ruled that the temporary ban on indoor church services violated the 1st Amendment’s guarantee of the right to exercise one’s religion freely. One of the concurring opinions caught Bloche’s attention for its fact-free analysis:

“Ignoring the science regarding duration of contact, Justice Neil Gorsuch taunted, in his concurrence, ‘It may be unsafe to go to church, but it is always fine to pick up another bottle of wine, shop for a new bike, or spend the afternoon exploring your distal points and meridians.’”

Someday the pandemic will end. I’d like to think that when that day arrives, health and medical issues will stop being excuses to have partisan fights. But Friday’s landmark decision in the abortion case Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health Organization has me bracing for more of the same.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom called the decision sickening and invited women to come here if they lacked access to safe and legal abortions where they lived. At the same time, the governors of Texas and Florida lauded the decision and were eager to see new restrictions take effect in their states.

It was an echo of states’ clashes over pandemic policies concerning lockdowns, de facto vaccine passports and mask mandates.

“This is a serious moment in American history,” said Newsom, who is joining with his counterparts in Oregon and Washington to defend access to reproductive health services. “This great divergence: red states versus blue states.”

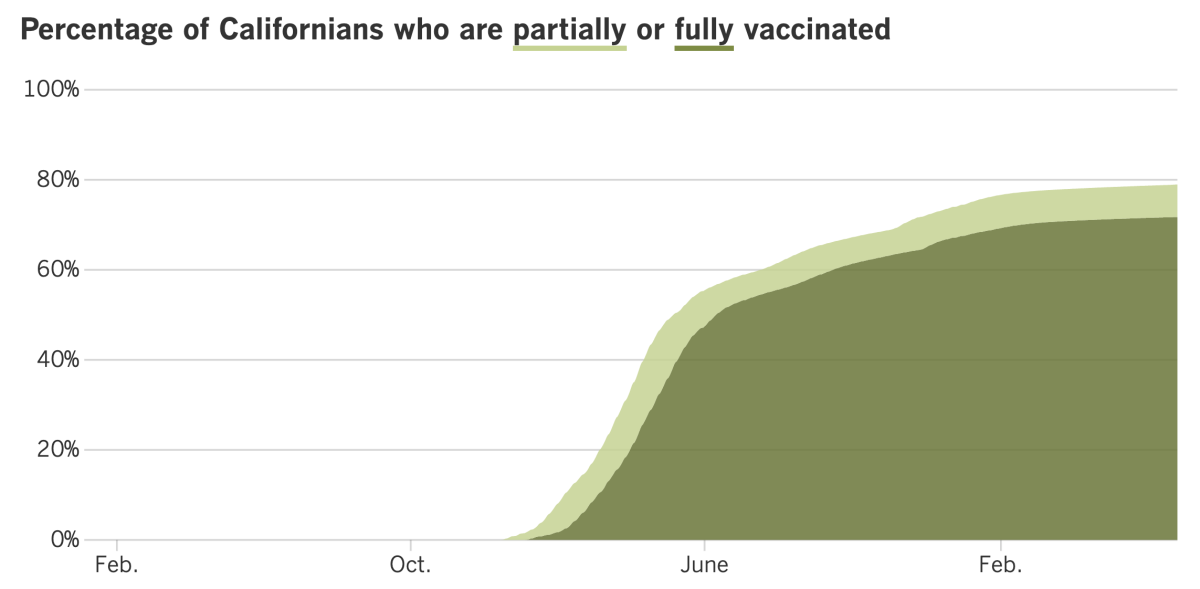

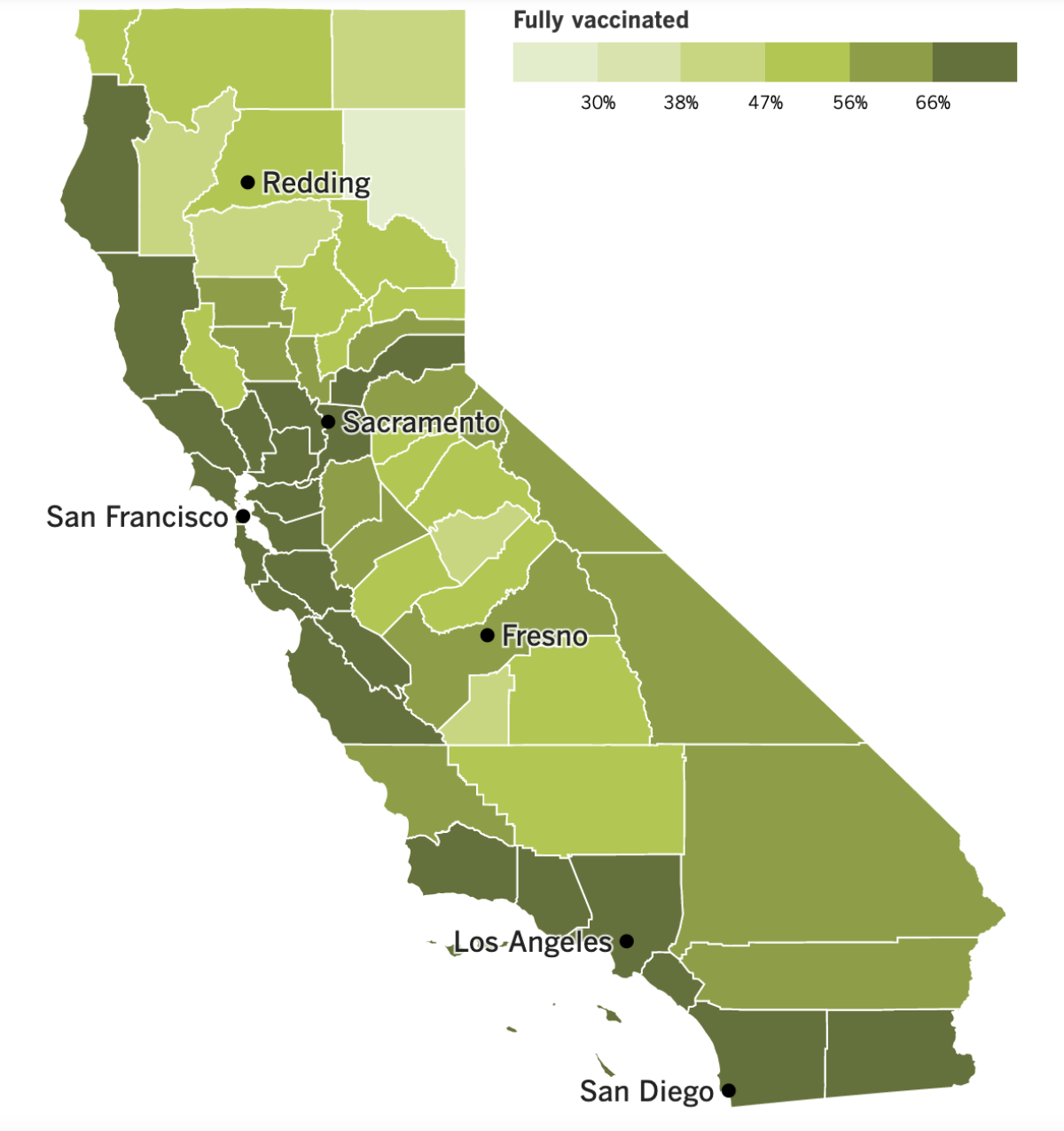

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

If getting this far into the newsletter has you going through Jan. 6 hearing withdrawal, perhaps news of another Capitol Hill hearing will tide you over.

Dr. Deborah Birx, who served as the COVID-19 response coordinator under Trump, went before a House panel on Thursday to answer questions about his administration’s handling of the pandemic. Birx told lawmakers that a lack of clear, concise and consistent messaging about the serious threat posed by the coronavirus created a false sense of security among Americans — including the federal officials who were slow to take decisive action.

“It wasn’t just the president; many of our leaders were using words like ‘we could contain,’ and you cannot contain a virus that cannot be seen,” Birx said. “And it wasn’t being seen because we weren’t testing.”

Birx spoke at length about her concerns about Dr. Scott Atlas, a neuroradiologist who came to the White House as a pandemic advisor in summer 2020. Atlas was of the view that it was OK to let the coronavirus circulate and infect low-risk people as long as vulnerable Americans were protected.

The problem with that, Birx said, was that it wasn’t possible to “magically separate the 50 or 60 million vulnerable Americans.”

When the public heard Atlas’ view, it sowed doubt in people’s minds and “created a sense that anything could be right,” she said. Atlas’ tenure also “destroyed any cohesion in the response of the White House itself,” she added.

Birx has previously said that 130,000 American COVID-19 deaths could have been averted after the pandemic’s first wave if the federal government had implemented an “optimal mitigation across this country.”

Speaking of COVID-19 deaths averted, a new modeling study estimates that COVID-19 vaccines saved nearly 20 million lives around the world in their first year of availability.

Using data from 185 countries, researchers estimated that vaccines saved 4.2 million lives in India, 1.9 million in the U.S., 1 million in Brazil, 631,000 in France and 507,000 in the United Kingdom. The findings were published Thursday in the journal Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The results “quantify just how much worse the pandemic could have been if we did not have these vaccines,” said study leader Oliver Watson of Imperial College London.

While we’re on the topic of COVID-19 vaccines, a Food and Drug Administration advisory panel voted Tuesday to recommend tweaking the shots so that they’re a better match for Omicron and its subvariants. Essentially all of the coronaviruses circulating in the U.S. today are some version of Omicron.

The shots now available in the U.S. were designed to neutralize the original coronavirus strain from Wuhan, China. As the virus has evolved, it’s gotten better at evading some of the immune system defenses induced by those vaccines.

The advisors voted 19-2 to update the shots in time for a booster campaign this fall. It’s not clear whether everyone would get a modified booster; they might be reserved for older adults and those at high risk.

If the FDA follows the panel’s advice, it will have to decide which strains and subvariants to target. A combination shot with multiple targets is most likely.

And in other vaccine news, CDC has formally recommended Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine for kids ages 6 to 17. The action gives parents a second choice, since versions of Pfizer and BioNTech’s vaccine have been available since last spring.

Moderna’s shot for 12- to 17-year-olds contains the same dose that’s given to adults; the shot for 6- to 11-year-olds contains a half-dose. In both cases, there are two injections given about a month apart.

And we’ll wrap up with two other pieces of good news:

Conditions in Alameda County have improved to the point that health officials there have been able to rescind a 3-week-old mask mandate that was in place for most indoor public settings. The COVID-19 community level for the Bay Area’s second-most-populous county progressed from “high” to “medium.”

Also, if you’d like to visit China, you’ll be able to see the country sooner. Instead of having to stay in a quarantine hotel for 14 days and then spending another seven days in home quarantine, visitors from abroad can now exit the quarantine hotel after seven days, followed by three days of home quarantine.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: Which COVID-19 vaccine should I get for my toddler?

This is a pretty low-stress question because there’s no wrong answer. Experts say the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines are equally good.

“Both vaccines are very safe and effective,” said Dr. Annabelle M. de St. Maurice, a pediatrician at UCLA Health. “Whichever vaccine is available to you first is the best vaccine.”

The two offerings have a lot in common. They’re both mRNA vaccines. They’re both made of the same stuff as the original adult versions, just packaged into a lower dose. They’ll both induce a young child’s immune system to make high levels of coronavirus-fighting antibodies. And most importantly, they’ll both reduce the risk of an infection — which also means they’ll reduce the risk of a serious illness or of developing long COVID.

That said, parents might have a personal preference for one over the other based on the vaccines’ differences, my colleague Ada Tseng reports.

The first is the administration schedule. Moderna’s vaccine (which is authorized for children ages 6 months to 5 years) requires two shots given four to eight weeks apart. If your child is immunocompromised, he or she will need a third dose at least four weeks after the second dose.

Pfizer’s vaccine (which is authorized for children ages 6 months to 4 years) requires three shots for everyone. The first two are given three to eight weeks apart, and the third one is needed at least eight weeks after the second.

Either way, your child will be fully vaccinated two weeks after their final dose. If you do the math, you’ll see that you can get there more quickly with the Moderna vaccine than with the Pfizer one.

The second difference is the side effects. For both shots, the most common ones seen in clinical trials were fever and pain, redness and swelling at the injection site.

With the Moderna shot, side effects for children ages 6 to 36 months also included irritability, crying, sleepiness and loss of appetite. For 4- and 5-year-olds, the additional side effects included fatigue, headache, muscle ache, chills, nausea, vomiting and joint stiffness.

In trials of the Pfizer vaccine, infants and toddlers ages 6 to 23 months also experienced irritability and decreased appetite. Children 2 through 4 had those as well, along with headache and chills.

Though the types of side effects are similar, the odds of experiencing a fever were higher with the Moderna vaccine, said Dr. Alok Patel, a pediatrician at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital at Stanford.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

The child raising his fist in the photo above is Will Maddock. He’s 23 months old and was born with a heart defect. For his entire life, his family has been in isolation to make sure Will is safe from the coronavirus. His mother, Jen, even quit her job.

Jen wasted no time getting Will and his 3-year-old brother, Jack, their first doses of COVID-19 vaccine last week at a pediatric clinic in St. Louis. She even dressed the boys in superhero capes to mark the occasion.

As you can see, Jen was pretty psyched to see Will get his shot. Having some immunity will make a huge difference for a kid who has only ever known life in a pandemic.

“He hasn’t even met all of our family,” Jen said.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.