Can Operation Warp Speed deliver a COVID-19 vaccine by the end of the year?

- Share via

To capture the speed and audacity of its plan to field a coronavirus vaccine, the Trump administration reached into science fiction’s vault for an inspiring moniker: Operation Warp Speed.

The vaccine initiative’s name challenges a mantra penned by an actual science fiction writer, Arthur C. Clarke: “Science demands patience.”

Patience is essential for those who ply the science of vaccines. But in that field, challenging economic conditions and a forbidding regulatory system converge with the immune system’s complexity and the resilience of microscopic pathogens. Add in drug companies’ preference for big profits and the result is a trash heap of failed and abandoned efforts.

In the last 25 years, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has approved new vaccines for only seven diseases. A vaccine to protect against the Ebola virus won approval just last year, three years after the epidemic in West Africa ended.

But in the midst of a COVID-19 pandemic that has killed more than 100,000 Americans and cratered the U.S. economy, Trump has shown little tolerance for science’s deliberate pace. And scientists, with fingers crossed, are falling in line.

The president declared that he wants 300 million doses — enough to protect as many as 90% of Americans — developed, manufactured and delivered by January 2021. He has ordered academics, government officials, private companies and the U.S. military to work together to make it so.

“That means big and it means fast,” Trump said. “A massive scientific, industrial and logistical endeavor unlike anything our country has seen since the Manhattan Project.”

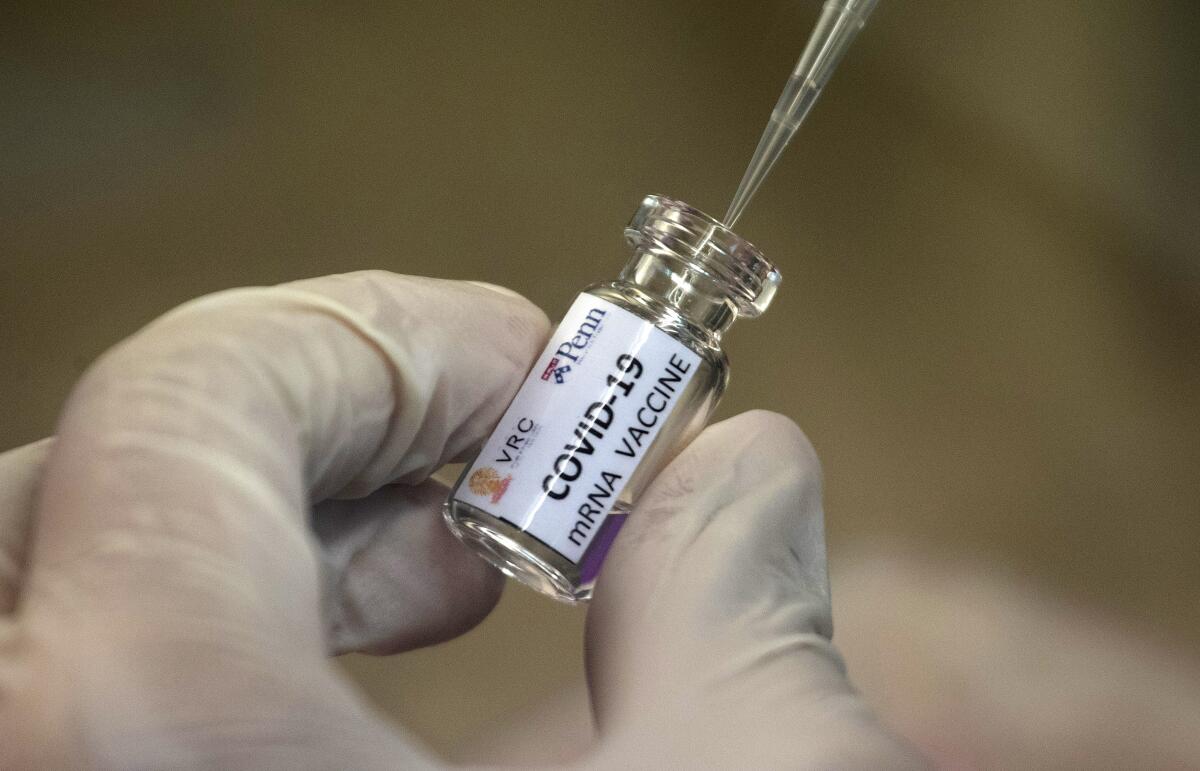

The new effort will demand the support, development, testing and assessment of several promising vaccine candidates by scientists at the National Institutes of Health, the FDA and companies and academic institutions across the world.

It will require the manufacture, procurement and storage of complex biologic medicines, as well as the vials, needles, syringes and storage equipment needed to deliver them. All will be needed on a massive scale.

And all that materiel will need to be transported, distributed and possibly administered by an army of logistics specialists.

Wherever possible, Operation Warp Speed envisions that many steps that have always followed each other in strict sequence — clinical trials and production, for instance, or government approval and supply-chain development — be done in parallel.

The program has already awarded a total of $2.16 billion to five companies with vaccine candidates at different stages of development.

President Trump outlined what he called a “warp speed” effort to develop and deploy a COVID-19 vaccine by year’s end. Even those leading the effort say chances of meeting that deadline are low.

To lead the effort, Trump tapped immunologist Moncef Slaoui, a pharmaceutical venture capitalist and former chairman of vaccines at the drug giant GlaxoSmithKline. The U.S. Army’s most senior logistics and procurement specialist, Gen. Gustave Perna, will be the operation’s chief operating officer. Both expressed confidence in the operation’s success.

Perna called the project “herculean.” Slaoui, who has been criticized for holding a major stake in at least one of the vaccine makers that stands to benefit from Operation Warp Speed, told Trump “we will do the best we can.”

The time is short and the stakes are high. Just over four months after the coronavirus announced its presence inside the United States, President Trump is determined to send the country back to work.

With no effective treatment in sight, and no indication that the coronavirus would “magically disappear,” as Trump has frequently predicted, a vaccine will be “the ultimate game changer” in the pandemic, according Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading expert on the outbreak.

“There’s never a guarantee of success,” Fauci said. But he added that he was “cautiously optimistic” that by winter, at least one of nearly a dozen promising vaccine candidates would have shown itself to be safe and effective in inducing immunity in humans.

Vaccine scientists are similarly cautious, especially of a testing schedule that will compress both the size and duration of safety and effectiveness trials — and even overlap them — in a bid to save time.

“It’s fine for politicians to say we’re going to have a vaccine next month,” said Mayo Clinic immunologist Dr. Gregory Poland. “But the literature is littered with false starts and unanticipated safety effects in vaccines.”

History tells us that rushing a vaccine for COVID-19 will prove more hazardous than if it’s done right.

Poland noted that a vaccine’s rarer side effects are often not recognized until it’s put into broad use. To ferret out an adverse outcome that only occurs in one person in 100,000, for instance, a company would need to test it in 384,250 people from broad backgrounds and with a variety of medical conditions, he said.

Such large trials are unlikely in the rush to field a vaccine, Poland said, and he fears the result could be a dangerous erosion of public trust. The yearly flu shot carries a risk of less than 1 in 1 million cases of the neurological complication Guillain-Barre syndrome, he said. And even with that low a risk, close to half of Americans refuse to get it.

“You have a whole spectrum of people out there who won’t be reassured by any amount of information,” Poland said. “If we don’t pay strict attention to safety, this is going to backfire.”

Money may help. Congress approved $8.3 billion in early March to fund federal agencies’ pandemic response. And scientists across the world have been scrambling to design vaccines to protect a population with no immunity to the deadly new pathogen.

Scientists in China, Kazakhstan, India, Russia, Germany, Sweden and the United States have brought 10 potential COVID-19 vaccines to the point where they are being evaluated in humans in some form. Another 115 are considered by the World Health Organization to be in the “preclinical” stage of development.

In some cases, these preclinical vaccine candidates are scarcely off the drawing board. In others, they are still being tweaked or tested in cells. Some are being tried in lab animals.

The prospective vaccines range widely in their design and novelty. There are those that challenge a person’s immune system with a killed or attenuated virus, the traditional approach used by the polio vaccine and other immunizations. Others are products of genetic engineering and have never been tried in a vaccine before.

Creating a vaccine capable of preventing the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 will take many months — if not a year or more. These are the steps involved.

The vaccine candidates also vary in their ease of manufacture, the number of doses a patient needs to gain lasting immunity, and the way they are administered.

FDA Commissioner Dr. Stephen Hahn has said his agency evaluated about 10 vaccine candidates in early studies. By late May, it had narrowed its focus to five candidates that will begin a rapid — and sometimes overlapping — progression through human studies of safety and effectiveness.

Meanwhile, the groundwork for large-scale production is already being laid. Trump has said that the U.S. military may aid in the manufacture, and companies with the capability to produce vaccines will be recruited to do so.

Given the pressing urgency of the administration’s deadline, vaccine candidates that can be produced fastest, transported most easily and administered to patients most efficiently will likely win the most and earliest support, experts said.

The redundancy built into Operation Warp Speed may also prove a vital safeguard against failure.

If the coronavirus shows signs that it is mutating in ways that could make one vaccine candidate ineffective, the scientific judges could swiftly shift their preferences toward a competitor that can be adapted more readily to changes in the virus. If rare but untoward effects show up with broader use, back-up vaccines could be brought on line. Some vaccines will be found to work better or worse in specific populations, and can be used accordingly.

The result will be an evolving panoply of vaccine choices, not only because some will be ready earlier than others, but because some will be more effective than others in certain populations.

“There will be of necessity multiple types of vaccines,” Poland said.

Michael S. Kinch, who directs the Center for Drug Discovery at Washington University in St. Louis, said that while there are pitfalls inherent to Operation Warp Speed, another pandemic offers comforting reassurance that in fielding the right drug, patience is an essential virtue.

In the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, the first generation of drugs was mediocre at best, he said. As scientists learned more about the virus and the disease it causes, the medicines became more effective.

“That may be a model for what we’re going to have here,” Kinch said. “We may not get the best vaccine up front. But hopefully it will be good enough and will be replaced later by better vaccines. We have may just have to live with that until we get a better one.”