Coronavirus Today: Flipping the script on COVID-19

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Karen Kaplan, and it’s Tuesday, June 21. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus in California and beyond.

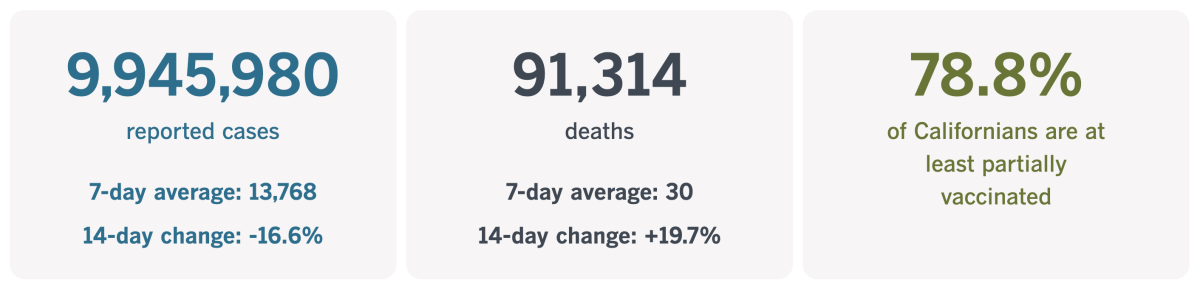

California has been averaging 13,768 new coronavirus cases per day over the last week. If health officials had reported a number like that back in the early months of the pandemic, we’d have been seriously freaking out.

What makes me so sure? It’s at least four times higher than any statewide case count reported during the pandemic’s first spring, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In fact, California didn’t see cases reach that level until late November 2020, when the devastating fall-and-winter surge was taking off. (We were definitely freaking out at that point.)

Now that we’re two-plus years into the outbreak, that case count barely registers with the public as a cause for concern.

Pretty much every public health leader from CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky on down has lobbied hard for people to get their COVID-19 boosters, but only 47% of eligible Americans have done so. State and local health officials “strongly” recommend that people wear masks in indoor public settings, but most don’t.

To some degree, this nonchalance is a sign of COVID-19 burnout. We’re tired of letting the coronavirus dictate what we can and cannot do. We just want our lives to go back to normal.

At the same time, there’s a reason that masks are “strongly recommended” but not required (at least, not yet): Although the Omicron variant is circulating widely and the current wave includes the third-highest peak of the pandemic, the number of people hospitalized with COVID-19 is still quite manageable, and deaths aren’t rising out of control.

That’s not to say the deaths are negligible — California reported 74 deaths on Monday and was averaging 30 deaths each day over the prior week. (Plenty of those deaths were preventable; the risk of death for unvaccinated people is more than 10 times higher than for those who are vaccinated and boosted, state health officials report.)

But compared with earlier periods of the pandemic, we have a lot more tools at our disposal to stave off COVID-19’s worst effects. And these tools are a lot more targeted than the stay-at-home orders, capacity restrictions and mandates we’ve had in the past.

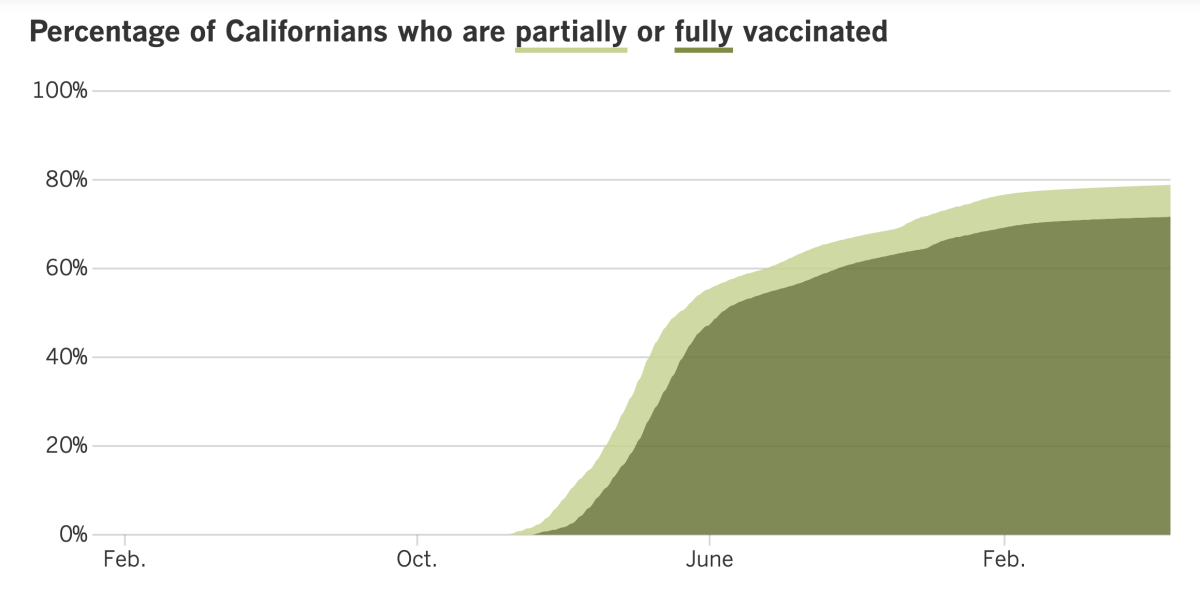

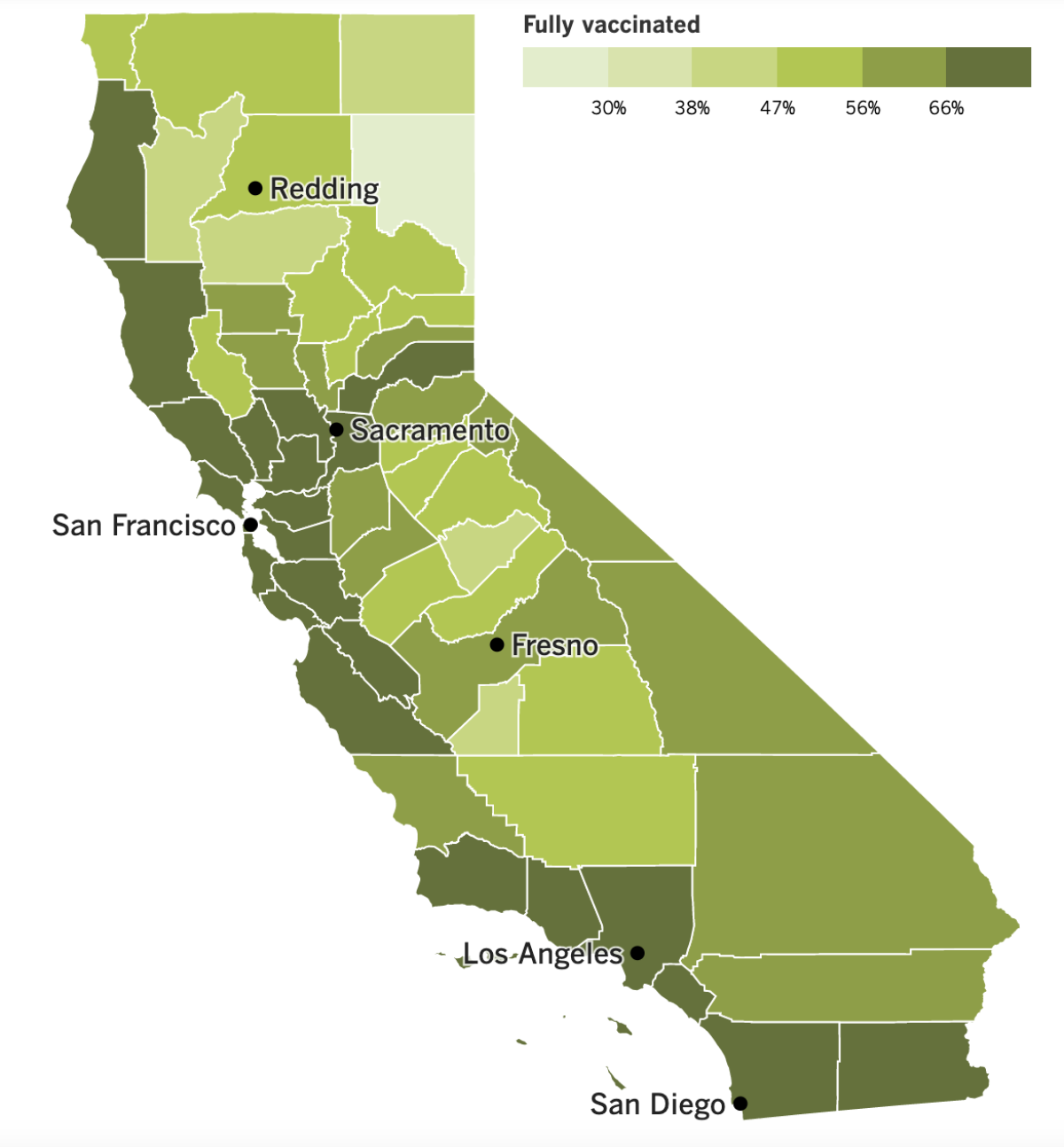

The most important tools are vaccines: 72% of Californians are fully vaccinated, and 58% of those eligible have received at least one booster shot.

Adding to that is the natural immunity people have gained by surviving an infection. In December, the CDC estimated that nearly 95% of Americans had coronavirus antibodies due to vaccination, past infection or a combination of both.

There are also plentiful coronavirus test kits, antiviral pills such as Paxlovid and Lagevrio (also known as molnupiravir) and the IV medicine Veklury (remdesivir). (Monoclonal antibodies used to be on this list, but they aren’t very effective against Omicron and its subvariants.)

And let’s not discount all the experience doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists and other healthcare professionals have acquired by caring for millions of COVID-19 patients.

This helps explain why the current wave, fueled by the Omicron subvariant known as BA.2.12.1, has seen far fewer hospitalizations than last year’s Delta surge — despite causing more infections.

The current wave peaked with about 16,700 new daily cases in California, compared with almost 14,400 during the Delta days. But Delta sent 8,342 coronavirus-positive patients to the state’s hospitals on its worst day, while BA.2.12.1 hasn’t surpassed 2,808.

ICU admissions diverged even more. With Delta, there were as many as 2,008 infected patients in intensive care units throughout the state at the same time. That number hasn’t risen above 300 in the current wave.

“At the very beginning of the pandemic, we noted right away the game-changers were going to be vaccines, easy access to testing and therapeutics — and now we have all those things,” Los Angeles County Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer told my colleague Luke Money.

That progress is something to appreciate, but it doesn’t guarantee we’re out of the woods. If another variant comes along that’s able to circumvent our vaccines and treatments, we could go back to seeing hospitalizations and deaths rising higher for a given increase in infections.

“We certainly are not at a level at these numbers where you would say, ‘OK, it’s now, quote, endemic, and we just go about business as usual,’” UCLA epidemiologist Dr. Robert Kim-Farley told Money.

“I think, though, it is probably indicative of what we might see in the future,” he added. “Hopefully these surges become fewer, more spread out and less intense as we go forward.”

By the numbers

California cases and deaths as of 4:40 p.m. on Tuesday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

Another way to look at things

If you’re having trouble swallowing the glass-half-full outlook outlined above, you’re not alone. What looks like hard-won progress to some seems like complacency — or even capitulation — to others.

Dr. Elisabeth Rosenthal is most definitely in the latter camp. In an Op-Ed, the editor in chief of Kaiser Health News lays out the litany of ways in which America has simply surrendered the fight against the coronavirus.

The country’s vaccination rate has stalled out at around 67% (though it’ll probably rise a bit now that the shots have been made available to the nation’s 18.7 million children under 5). Boosters are even less popular than the initial doses.

President Biden requested $22.5 billion to continue funding the country’s COVID-19 response, including money to pay doctors who care for uninsured patients and cash to buy vaccines, tests and treatments. The Senate responded with a $10-billion package that doesn’t include any funds to help squelch outbreaks overseas. Now even that compromise bill is being held up by the politics of immigration.

Dr. Ashish Jha, the White House COVID coordinator, has warned that “we would see a lot of unnecessary loss of life” if the money doesn’t materialize. So far, that hasn’t been enough of an incentive to break the impasse.

The lack of urgency is shared by state and local governments, in Rosenthal’s view. They’ve rescinded mask mandates even for high-risk settings, including places like bars and music venues where people crowd together indoors. Health officials aren’t acting with urgency to get more people boosted even though it’s become increasingly clear that a booster dose is essential to ward off Omicron.

When the government won’t take preventive measures seriously, it’s hard to blame private employers for following suit. Few stores still require workers and customers to mask up; even if mask rules are still posted, they’re rarely enforced. (The latest example: Broadway theaters in New York City announced Tuesday that mask use during performances would become “optional” next week.)

In March, the Biden administration unveiled a plan to help Americans coexist with the coronavirus as safely as possible. The plan’s stated goal is “to get back to our more normal routines.” Who wouldn’t get behind that?

“Unfortunately, in response, our elected representatives and much of the country essentially sighed, preferring to move on and give up the fight,” Rosenthal writes.

The problem isn’t just that people are sick of caring about public health. The problem is that it’s inherently difficult to make people care about it.

“That’s because if public health officials are respected, well-funded and allowed to do their job here’s the result: Literally nothing happens,” Rosenthal writes. “Outbreaks don’t lead to pandemics.”

Health officials can’t go around crowing about the bad stuff that didn’t happen. But when people don’t take their warnings seriously, they’re the ones who are blamed.

They’re also the ones who get short shrift from politicians and the public. In the year before the pandemic, the CDC’s budget was cut by 9%, according to the Trust for America’s Health. Money for programs like suicide prevention and HIV care was only slightly higher in 2020 than it was in 2008, after accounting for inflation.

At the state level, spending on public health didn’t see significant growth between 2008 and 2018, except for programs aimed at preventing injuries, according to a 2021 study in the journal Health Affairs. State health departments weathered big cuts to cope with the Great Recession, and that funding hadn’t been restored by the time COVID-19 came along, leaving them “ill equipped to respond,” the study authors wrote.

The cuts have resulted in the elimination of at least 38,000 state and local public health jobs, Rosenthal notes. “That’s partly why states and cities have yet to spend much of the $2.25 billion allocated in March 2021 by the Biden administration to help reduce COVID disparities,” she writes. “There are now too few on-the-ground public health officials who know how to spend it.”

Public health was front and center for awhile in the pre-vaccine era, when people were more afraid of the coronavirus and of having to use an iPad to say goodbye to a loved one hooked up to a ventilator in an ICU. Now our attention has shifted to mass shootings, inflation, the war in Ukraine and the abortion case before the U.S. Supreme Court.

A trio of anthropologists from George Washington University agree it’s important to keep COVID-19’s victims at the top of our minds, especially when so much of the culture is determined to behave as if things are already back to “normal.” And they have some ideas for doing so.

Sarah E. Wagner, Roy R. Grinker and Joel C. Kuipers start by suggesting a national commission to take a hard look at how the country allowed the pandemic’s death toll to exceed 1 million. “By documenting how we got here, the country would be holding itself accountable — ultimately an act of healing for survivors,” they write.

They also recommend a national day of remembrance for COVID-19 victims. Resolutions in both the House of Representatives and the Senate would turn the first Monday in March into “COVID–19 Victims and Survivors Memorial Day.”

“A designated national memorial day would make the pandemic visible for decades to come,” they write.

California’s vaccination progress

See the latest on California’s vaccination progress with our tracker.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

In other news ...

It’s been a year and a half since the first COVID-19 vaccines received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. During that time, the conversation around the vaccines has shifted from how to stop unscrupulous people from jumping the line to how to entice holdouts to roll up their sleeves.

So if you found yourself feeling ho-hum about the latest vaccine news — that COVID-19 shots are now available for kids as young as 6 months — try looking at it from McKenzie Pack’s perspective.

Pack has a 3-year-old son named Fletcher. He’s not old enough to remember a time before the pandemic. But once the vaccine builds up his coronavirus immunity, he can start doing things he would have otherwise taken for granted.

“He’s never really played with another kid inside before,” McKenzie Pack said. “This will be a really big change for our family.”

That change was made possible by the FDA’s decision to grant emergency use authorization to two COVID-19 vaccines for infants, toddlers and preschoolers. Both are reformulated versions of the mRNA vaccines available to U.S. adults.

The one from Moderna is a two-shot series for kids ages 6 months to 5 years. Each injection contains one-quarter the dose used for adults. The two shots should be given four to eight weeks apart; young children with compromised immune systems should get a third dose as well.

The vaccine from Pfizer and BioNTech requires three doses for everyone. The first two shots are given three to eight weeks apart, and the third one follows at least eight weeks after the second dose. It’s made for children ages 6 months to 4 years, and contains one-tenth the dose used in the adult vaccine.

The CDC’s vaccine advisory panel spent two days debating the pros and cons of the vaccines before endorsing them on Saturday. Walensky accepted their advice and urged parents and caregivers to make a date with a needle, even for children who’ve already had COVID-19.

In clinical trials, the pediatric vaccines were less effective than the adult versions were when they began rolling out 18 months ago. That’s because new coronavirus variants — especially versions of Omicron — have become more adept at evading antibodies induced by the shots. The trial data suggested the new vaccines would probably reduce the risk of COVID-19 symptoms in young children by 30% to 60%.

“We cannot let the perfect be the enemy of the good,” said Dr. Oliver Brooks, chief healthcare officer of Watts Medical Corp. in Los Angeles and a member of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. “That’s the bottom line.”

The advisors said they were persuaded by evidence that young children’s antibody response to the new vaccines was on par with the antibody response seen in older children and adults, two groups for which the vaccine has been shown to be protective. Clinical trials also established that the vaccine was safe — among nearly 8,000 young children, there were no deaths and very few serious adverse events, such as high fever.

The Western States Scientific Safety Review Workgroup — a coalition of public health experts from California, Nevada, Oregon and Washington — conducted its own review over the weekend and announced its support for the new vaccines on Sunday.

California has ordered almost 400,000 doses, and it began allowing parents and caregivers to book appointments on the My Turn site on Tuesday. But many providers that showed up in search results didn’t appear ready to accommodate the youngest children.

The website for the L.A. County Department of Public Health notified users that vaccines for children younger than 5 were on the way. It provided a list of sites that were “expected to offer the vaccine as soon as it arrives.” A spokesman for the department said most of those sites should have doses available by Wednesday.

Both the county health department and the state offered a heads-up that pharmacies couldn’t vaccinate children under age 3. That means a visit to a pediatrician or health clinic is in order.

In other COVID-19 vaccine news, a study published last week in the New England Journal of Medicine found that two initial doses without a follow-up booster offered essentially no lasting protection against an infection with Omicron. Researchers also reported that an infection was about as good as a booster at preventing a new Omicron-fueled illness.

On the plus side, the study found that either type of immunity offered lasting protection against serious illness, hospitalization and death.

“I think this is really the important part: The immunity against severe COVID-19 was really very much preserved,” said study co-author Laith Jamal Abu-Raddad, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Weill Cornell Medicine-Qatar.

Moving on to treatments, Pfizer said Paxlovid didn’t seem to help COVID-19 patients who were not at high risk of becoming severely ill. That became clear in a study testing its antiviral drug in a broader population of people who were relatively healthy and unvaccinated, or who were fully vaccinated but had a medical condition that made them more vulnerable to a serious case of COVID-19.

California is having trouble getting Paxlovid to patients who need it. In the month since the state began its “test-to-treat” system, fewer than 800 people received a prescription, even though thousands of Californians became infected each day.

The program’s goal is to make antivirals available right away to high-risk patients who test positive for a coronavirus infection, since the drugs work best when taken shortly after symptoms begin. A total of 1,219 people had been screened for the drugs as of mid-June, and 768 got Paxlovid pills.

“I think it’s a new concept that people are still getting used to,” said Katharine Sullivan, who oversees a test-to-treat site in west Berkeley.

And finally, the World Health Organization’s latest weekly report on COVID-19 said there were more than 8,700 deaths in the week that ended June 12. That number is notable because it represents a 4% increase over the prior week and the first increase since early May.

The Americas saw the largest increase in the COVID-19 death toll (21%), followed by the Western Pacific region (17%). Europe, Southeast Asia, the eastern Mediterranean and Africa all saw declines.

Your questions answered

Today’s question comes from readers who want to know: What’s the criteria for having a “high” COVID-19 community level?

This is important because if and when L.A. County crosses this threshold and stays there for two weeks, its indoor mask mandate will return.

To back up for a moment, COVID-19 community levels are a measure the CDC uses to gauge how the coronavirus — and the disease it causes — are affecting people’s health in a particular place, either directly (through illness) or indirectly (by placing undo strain on local healthcare resources, making them unavailable to others). They come in three flavors: “low,” “medium” and “high.”

Three factors determine a county’s COVID-19 community level: the number of new infections diagnosed over the last week; the number of new COVID-19 patients admitted to local hospitals over the last week; and the percentage of hospital beds occupied by patients with COVID-19.

There are multiple combinations of these variables that would qualify a county (or state or territory) as having a “high” COVID-19 community level.

Start with the coronavirus case count. See whether your county has recorded at least 200 new cases per 100,000 people over the last week. L.A. County did: It saw 337 cases per 100,000 residents in the last week.

Since we’re over the 200 mark, we’re ineligible for the “low” level. But we can stay in the “medium” level if we have fewer than 10 new COVID-19 hospitalizations per 100,000 residents over the last week and fewer than 10% of hospital beds are filled by COVID-19 patients.

The latest CDC figures show that L.A. County hospitals are admitting 7.3 new COVID-19 patients per 100,000 residents per week, and that 3.5% of hospital beds are devoted to patients with COVID-19. That means our COVID-19 community level is still “medium.” But if either metric climbs too high, we’ll be reclassified into the “high” category.

If our new case count were below 200 per 100,000 residents per week, we could still have a “high” COVID-19 community level if we had at least 20 new hospitalizations per 100,000 per week, or if at least 15% of hospital beds were filled with COVID-19 patients. However, those combinations are a lot less likely.

You can look up the COVID-19 community level for any U.S. state, territory or county on the CDC website.

We want to hear from you. Email us your coronavirus questions, and we’ll do our best to answer them. Wondering if your question’s already been answered? Check out our archive here.

The pandemic in pictures

He was the last person I expected to catch the coronavirus, but this pandemic is full of surprises.

The National Institutes of Health announced Wednesday that none other than Dr. Anthony Fauci had come down with a mild case of COVID-19. Fauci, 81, is fully vaccinated and double-boosted and still well enough to work from home, where he is isolating according to CDC guidelines.

Less than two months ago, the nation’s top infectious disease expert heralded the arrival of “more of a controlled phase” of the pandemic. But he was quick to add: “By no means does that mean the pandemic is over.”

In this case, I’m sure he wishes he’d been wrong about that.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Here’s where to go: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get a test? Testing in California is free, and you can find a site online or call (833) 422-4255.

Americans are hurting in various ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, as well as resources for people experiencing domestic abuse.

We’ve answered hundreds of readers’ questions. Explore them in our archive here.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.