- Share via

When Hannah Coleman and husband Alvaro Vela bought a century-old home in Culver City eight years ago, the first-time home buyers were charmed by the home’s Craftsman details — sweeping front porch, clapboard siding, corbel-accented roofline and arched windows — as well as an expansive backyard filled with mature fruit trees.

Shortly after purchasing the home, which is registered as a local historical landmark, the couple hired Los Angeles architects Peggy Hsu and Chris McCullough, of Hsu McCullough, who helped them to open up the second-floor attic, add much-needed insulation and install a covered back porch and raised deck for outdoor dining.

“We lived in the downstairs bedroom because it was too hot to live upstairs, and the ceilings were so low,” says Coleman, who’s a research analyst in the healthcare industry. “But it was OK because it was just the two of us.”

At first, the house seemed perfect. But when the couple began having children — they now have two sons who are 1 and 3 — and their extended family came to visit for long periods of time, they outgrew the 1,600-square-foot floor plan. The COVID-19 pandemic didn’t help when it forced the couple, who are both 37, to work from home.

“It’s important for us to have our family stay with us,” Coleman says. “We have family members in Colombia and Hawaii who stay with us for two to four months at a time. We wanted a designated space for them.”

When they casually looked for a larger home in their neighborhood, however, they realized that, like so many Southern Californians, they were priced out of L.A.’s competitive housing market. “We really wanted to make it work in our house because we love the house and the lot,” Coleman says.

As much as they cherished the 1922 home, they were less enamored with its detached garage, which Vela, a sound engineer, turned into a studio. Although the garage worked as a studio, it felt out of place with the home’s Arts and Crafts style.

This tiny, two-story Los Angeles ADU functions as a multipurpose housing space, gym, office and pool house for friends and family.

In 2020, soon after California changed the covered parking requirements for ADUs to make it easier to build more housing, the couple rehired the architects to help them build an accessory dwelling unit that would give them more room and preserve the home’s Craftsman architecture. In Culver City, no new or replacement parking was required for the ADU after the garage was demolished, which didn’t affect Coleman and Vela because they have room to park four cars on a long driveway on the west side of their yard.

Seeing so many McMansions in Los Angeles, Coleman says she “didn’t want a mega-house. We thought of the ADU as more of an extension of the house. We are not sure if we are going to stay in Los Angeles, so we thought it would add quite a bit of value to our home.” Looking ahead, she says, they feel that they will be more likely to rent out the unit or sell their home as compound living.

Tucked behind the main house, the resulting 700-square-foot ADU, whose exterior was custom-milled to match the main house, exudes Craftsman charm. That’s because the couple wanted the home to “mimic some of the aspects of the house,” Coleman says, while adding modern touches such as a Fleetwood pocket sliding door in black anodized aluminum finish at the front of the ADU.

“The houses are fraternal twins,” says McCullough, who notes that about a quarter of the inquiries their firm receives are regarding ADUs. “The front of the house is so amazing. It was a blueprint for the ADU.”

Preserving the yard was another priority for the family. “We could have gone up to 1,200 square feet but we wanted to maintain the outdoor garden space,” says Hsu. “It was about nestling the ADU into the backyard and not disturbing the trees as well as creating a space between the ADU and the main house that serves as a playground for the family.”

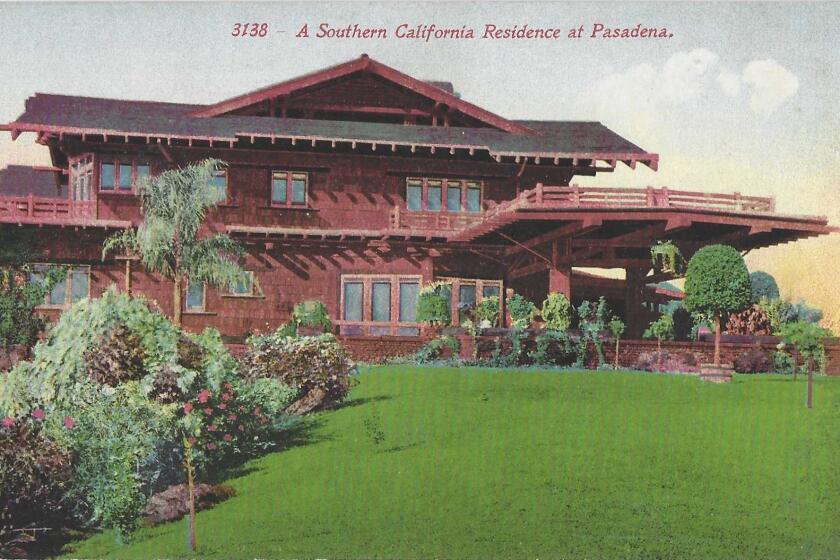

If you’re feeling the springtime itch to go look at open houses, first of all, we’re sorry about the sticker shock. But here’s a primer on the hodgepodge of home styles you’ll see around Southern California.

Standing in the backyard, the connection between the two homes is evident in the detailing, buttresses, wood carpentry and custom replica 1920 wood windows by T.M. Cobb that match the main house’s existing windows. At a quick glance, it’s hard to tell the new construction from the original home.

“All of the spatial clues are from the main house,” McCullough says. “We were not trying to make it modern. We wanted people to say, ‘Was this originally here?’”

The ADU was designed to have three distinct spaces: a sound studio for Vela, a guest bedroom and an open, airy family room. Although it connects to the family room, Vela’s studio, which pops out from the principal floor plan, feels separate from the rest of the house.

Likewise, a pocket door can close off the bedroom to provide privacy for guests. A loft, accessed by an iron ladder, provides overflow space for guests and a small kitchenette in the hallway accommodates basic cooking needs while saving space in the tight quarters. Further enhancing the aesthetics of the backyard, the architects installed a new electrical main power drop at the rear of the ADU that provides underground electrical service from the ADU to the main house. That way unsightly overhead power wires are underground and not overhead.

Although the exterior mirrors the Craftsman architecture of the main house, the light-filled interiors have a modern feel with vaulted ceilings, oak floors and custom-built white oak Shaker cabinets. “We all agreed that we wanted the ADU to have a connection to the house,” Hsu says. “It is evident in the detailing and the wood carpentry. But it definitely has its own character.”

Construction began in January 2021, and it took nine months to complete the transformation at a cost of about $400,000, which McCullough predicts would be about $100,000 more today due to supply chain and labor issues. Since then, Coleman says, they have hosted as many as eight family members at once. “Now it’s like a hotel,” she says, “and we have to write down when people are coming.”

Sign up for You Do ADU

Our six-week newsletter will help you make the right decision for you and your property.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Last year, when Vela’s parents came for four months, they stayed in the main house during the day while Vela and Coleman worked in the ADU. During the summer months, the family would walk to parks, Platform or downtown Culver City and also play in the backyard with Vela and Coleman’s kids after school. Then, in the evenings, they would eat together as a family, and Vela’s parents would retire to the ADU. “It’s so nice to have the extra space when everyone is living together,” Coleman says.

Although Coleman says she has never been a fan of new development, their ADU has changed her mind. “It’s 700 square feet but it feels huge,” she says. “I almost prefer it to the main house.”

More Los Angeles ADUs

They worried about long-term housing for their disabled son — until they built an ADU

This ADU rental with windows galore is a houseplant lover’s dream

How an aging Tudor’s ADU reunited a family and brought them closer together

They were spending all their income on rent. A garage turned ADU saved them

How a struggling single mom built an ADU, without killing a 60-year-old tree

How an unremarkable alley-facing garage in West L.A. became a stylish ADU

They turned a house full of cockroaches and code violations into a ‘must have’ home — and ADU

They turned a one-car garage into a stunning ADU to house their parents. You can too

He challenged himself to build an ADU for under $100,000. What’s his secret?

She built a granny flat in Echo Park: How it saved her during the pandemic

More to Read

Sign up for You Do ADU

Our six-week newsletter will help you make the right decision for you and your property.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.