- Share via

I’m floating on a longboard and the water is calm. The minimal wind or whitewash in the waves has the board gliding across the water, cutting through it like a smooth knife dipping into room-temperature butter. It’s “glassy,” in surfer speak. You can almost see your reflection. This brief moment of serenity is an ideal time to talk, to think, to process, because when the time does come to catch that wave, there won’t be room for much else. Not hesitation. Not second guessing. Just sending it, fully.

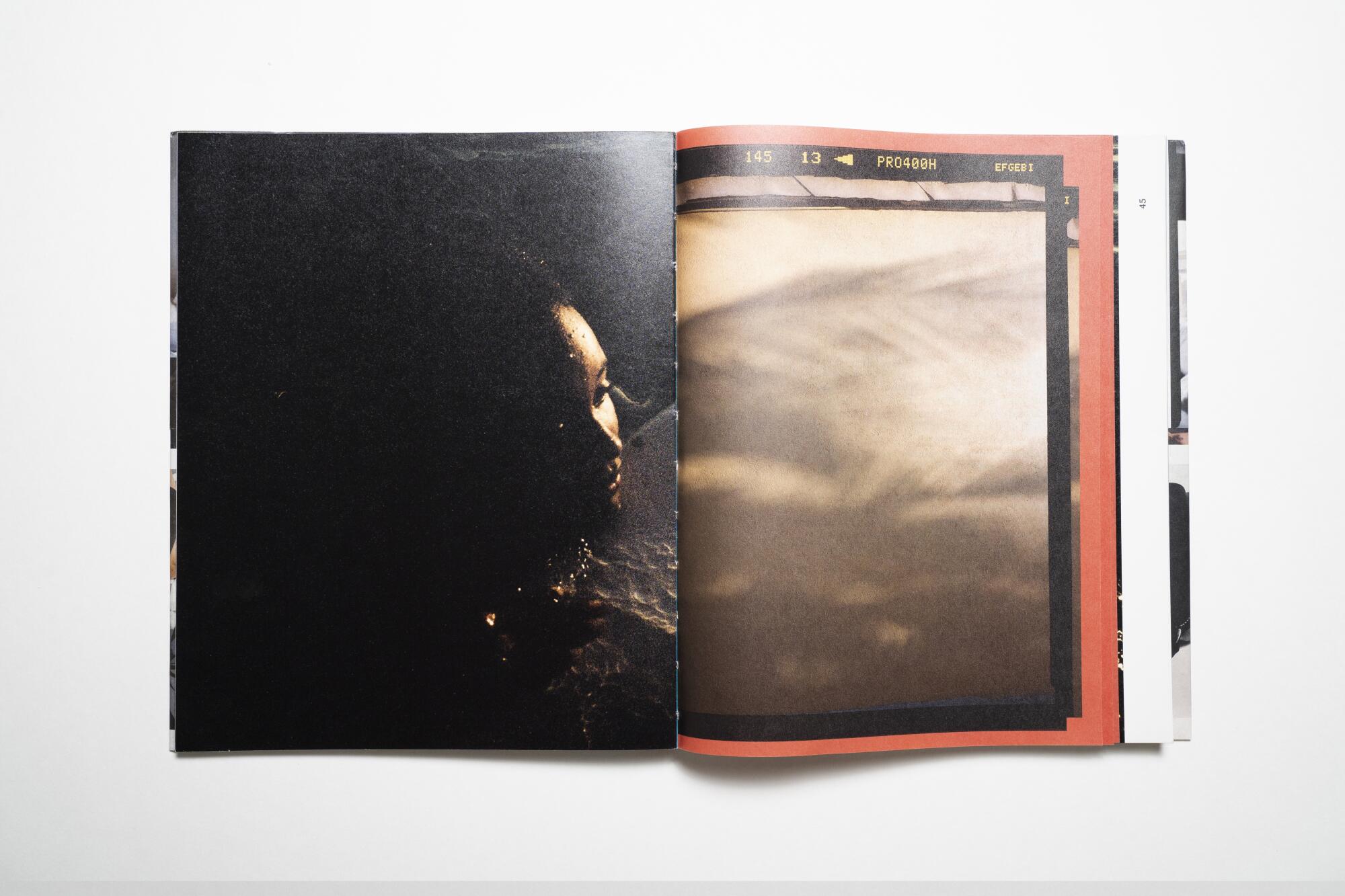

When you’re surfing, one of the main things you’re trying to do is keep your head above water. This is intended in the most literal way possible, but as you might imagine it also transcends into a metaphor for life. Photographer Gabriella Angotti-Jones knows this duality well. Her first book, “I Just Wanna Surf,” crystalizes the way the cyclical nature of trauma and healing mirrors the nature of chasing a wave. Through warm photos and personal text, Angotti-Jones dives deep into her experiences with depression, understanding the mechanisms of racism through surfing, community, womanhood and Blackness. Despite learning to surf as a child in San Clemente, Angotti-Jones says it took years to feel surfing was hers. Her life story as a Black surfer girl is an intimate look at making an identity your own.

Images of Gabriella’s friends fill the pages. Black women and nonbinary surfers are captured in their element: the quiet moments spent waxing a board, being enveloped by the ocean, the smiles that come after a surf. They might make you feel, too, like you have salt in your curls; or like if you touch your skin in that moment, you might also be slightly sore from the sun. Angotti-Jones’ words have a casual intimacy, like they’re ripped from the pages of her personal diary: “I think surfers are addicted to feeling present. I long for days where my body can interpret the waves faster than I can process my thoughts, where I become one with the water. I don’t want the ocean to be a place of pain anymore. I want it to be one of revelations.”

When I learned Gabriella was releasing the book, I sent her a text: “How would you feel about me going surfing with you?” I’ve written about surfing, heard friends talk about it for years — mostly using phrases like, “it’s hard to describe,” but this would be the first time I’d see for myself. G texts me back almost immediately. “Yesssss.”

It started with Gabriella checking the wave report. We’d go to El Porto right before sunset, which isn’t her favorite, but it would do. She met me there in her white pickup truck, a tall yellow board protruding out of the back. She handed me a wetsuit, which I changed into under a huge hooded towel. I slathered on sunscreen on my T-zone and quickly learned the correct way to hold the board: under my arm, against my side. After a lesson on the sand we took to the ocean. I told Gabriella that I felt safe with her.

Ebony Beach Club shows why partying is a restorative practice. Whether you’re in need of healing from witnessing or experiencing pain — in the world, in yourself — celebration offers a clean slate.

During still moments in the water, G and I cracked dark jokes about our mutual anxieties and sat in silence while we stared into the horizon. When a medium-sized wave arrives, Gabriella quickly tells me to hop on, to paddle, paddle, paddle and jump up. It’s all happening faster than I imagined. Time betrays me, and I only manage to get up on my knees before the wave reaches the board. I ride to the shore that way, like a parody of a golden retriever surfing. I hear a scream of approval from G, who was behind me the entire time watching. A different time I get up and ride the wave completely, a rush of pride washing over me. I’m participating in a what feels like a ritual.

One time on a board does not a surfer girl make — as Gabriella writes in her book, the culture is about humility and respect, waiting until your time comes and learning as much as you can while you do — but she’s hyping me up, giving me what she didn’t get when she started surfing as a kid: love, not tough love, just love. And in the moment, it feels good to be tethered to something bigger than myself. Even if it’s a 9-foot board.

🏄🏿♀️🏄🏿♀️🏄🏿♀️

JJ: How are you feeling?

GAJ: Overwhelmed. I didn’t realize when I was making [the book] that I was going to talk openly about all my triggers and how I almost killed myself. I didn’t think that was going to be a huge part of the project and kind of a crux of it. I didn’t really realize the impact of putting that in a book and putting it out there, how therapeutic that would be. I am a really private person — my friends know who I am, but I don’t broadcast how I feel. It’s interesting that it took me so long to address my depression in a very public manner. The irony is not lost on me.

JJ: Tell me about the format of the book.

GAJ: The format was very much inspired by late `90s, early 2000s surfing and skate magazines. It’s kind of modern photo book meets that ethos of skate, surf, die, f— you. That kind of aesthetic. [The text] is formatted like the process of surfing and letting thoughts come to you, meditating. It starts coming out from under the water, having thoughts bursting through, and then these waves metaphorically hit, you have different feelings, and then by the end, you go back underneath again. It’s that cycle of paddling out.

JJ: Why did you decide to do it like that? I feel like that’s pretty unique, especially because it’s been a while since the heyday of those subculture magazines.

GAJ: I’m tired of not seeing my friends’ attitudes, how they look and how they act reflected in surf media. It’s been so commercialized. I really wanted to just go back and show why I surf and what brought me into it. That time period was so traumatizing to me — I felt like I didn’t fit in, and I really wanted to make something where it was a bunch of people that looked like me in that format and shot in that style. What we do is no different — it’s actually core as f—, you know what I’m saying?

JJ: I’ve never actually asked you how you started surfing.

GAJ: I learned when I was 8. I think it was called Aloha Beach Camp and it was hosted by the Colapinto family [professional surfer Griffin Colapinto’s family]. I was attracted to it. It felt bigger than me. It felt very important and I wanted to be a part of it. I remember it was this big force that I wanted to master and understand very deeply. I later learned that a lot of water men and women feel that similar calling. I was very honored that I felt that.

JJ: You mentioned to me in the water earlier how surfing was the first time you realized racism’s role in your life.

Getting called a racial slur while surfing Manhattan Beach changed how Justin ‘Brick’ Howze and Gage Crismond view their role in the sport.

GAJ: I literally talked about that so much in the book. I go into all the little microaggressions that led up to me quitting. In action sports, in watersports in particular, there’s this culture of like, “If you can’t handle it, get out.” Because it’s dangerous — you’re a danger to yourself and others. So there’s this constant checking that happens in the water: a lot of commentating on where you should sit, where you should stand.

I think that happened a lot more so when I was growing up, especially in a place like San Clemente. With the normalization of that culture, especially as a kid, there’s an adultification process that happens. That, compounded with me being a young Black girl … I don’t think that treatment towards me was malicious. I think it was just a part of the culture and maybe like a weird backhanded way of support. But I think for me, I didn’t realize how sensitive I was with the way I looked in such a homogenous environment. I realized, “Oh, am I different? Are they treating me like that because I’m different?” And then I started really getting into my head. “They’re asking me if I’m from here all the time. What do they mean by that? They’re asking me if I’m on vacation. I’m not on vacation. It’s December.”

JJ: As a child, you can’t suss out what their actual intentions are. You get that over and over and you start to question yourself, and then see yourself in that way. You become self-conscious.

GAJ: That’s the most Southern California way of racism ever.

JJ: [Laughs]. Yeah, like, “Where you from, dude? You from around here, or?”

GAJ: Super passive. So loaded. So easy to just be like, “No, I didn’t mean that.” Because maybe they didn’t. But they’re unaware. It also helped me realize racism isn’t just how people overtly treat me. It’s how the system internalizes within myself and makes me hate myself. It makes me question myself and create that doubt of, “Do I belong in this space? Should I exist here? Why am I here?” And that’s so messed up.

JJ: You ended up quitting. When did you get back to surfing?

GAJ: When I started this project.

JJ: Did you intentionally start again because you had this project in mind?

GAJ: I’ve always had this attraction to the ocean. I was wanting to talk about it, and, well, figure it out. I had these deep feelings about it. After I finished my internship with the New York Times, everyone kept telling me I shot like a newspaper photographer. That would piss me off, because that’s not who I am. I literally did journalism so I could leave it. I remember doing research and I was like, “Oh, I want to do something on surfing.” My boyfriend at the time [introduced me] to all these Black girl surfer accounts and I flipped out and contacted them. I met my two now-really close friends, Shelby Tucker and Olga Diaz. They were just learning how to surf. [I’d] literally never seen a Black person surf. We became friends because it’s so comforting to be around people who have a similar background as you, look like you, enjoy similar things. It’s a special bond.

JJ: So, that was the first time you saw a Black person surf. What did that moment feel like for you?

GAJ: I felt protective of them.

JJ: Do you think that was like your inner child coming back out?

GAJ: OK, therapy [laughs]. I would be lying if I say I didn’t. I wanted to be protective of them because the culture spat me out. I don’t want that to happen to them. In a lot of ways, I wrote this book as a kind of a guide. I wanted it to be for someone who grows up wanting to surf — they can pick up the book and be like, “Oh, s—, she went through this.” I wanted to break down the dynamics for people because I don’t think it’s a solely white person issue. I think it’s bigger than that. It’s more of a societal issue and a lack of acknowledgement of the impact of racism on this country in our everyday lives.

JJ: You started the project a year before the 2020 uprisings, when a lot of Black people in L.A. were surfing in protest or taking to the water for the first time. Did that validate the work you were doing?

GAJ: During COVID, more people started surfing because it was one of the few things you could do. And I also think that Black Angelenos started reclaiming L.A. as theirs again. I feel like after 2020, we started seeing a lot more of those Blackity Black Black events, like Black Market Flea, like Ebony Beach Club’s Beach Bounce. Me and my friends made a conscious decision to make surfing a part of that resurgence of Blackness in L.A. Because it’s ours too.

As these photos show, new friends are made, camaraderie is built and sometimes the bonds become the genesis for new meet-ups, new skate crews to be born.

JJ: Is this the first time that you feel like you’ve had a community?

GAJ: I’ve never really felt comfortable around other people because of my depression. I didn’t really know how to relate to people. It’s it’s hard to talk about depression. It’s hard because it’s so personalized, and doesn’t really make sense. So I never really allowed people to get to know me, because I just didn’t feel like I had value. And I think because I felt so safe in this group of people that saw me for who I was — which is, like, a parking lot ocean b—, I felt comfortable, and I felt like I could be myself. I’d never met another person that looked like me that was into the ocean. I wanted that so badly when I was little.

JJ: Imagine 12-year-old Gabriella was at a print fair or a bookstore and came across “I Just Wanna Surf.” What would that have meant?

GAJ: I would have flipped out.