- Share via

Neoliberalism’s tight psychic grip on Western society is no more. Celebrities are obsolete archetypes, fallen deities, vying for relevance against what I like to call “bonnet TikTok,” where men and women gather on social media in their most unflattering house clothes and address one another about everything from war to quantum physics — just like that, no adornments (unless the jolting intimacy of an unsolicited glimpse into a stranger’s leisure is a costume here).

We just witnessed a presidential election where the liberal Democratic candidate had the cultural and social capital of Beyoncé, Taylor Swift, Usher, Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, J.Lo, John Legend — and all this hype that made the campaign trail feel like MTV’s Video Music Awards only affirmed the candidate’s inadequacy. These celebrities she employed to make rallies into policy-less spectacles were in part to thank for her loss. Bonnet TikTok spent as much time as these stars trying to rehabilitate the glamour of the Democratic Party, roasting it and every celebrity who would dare, under current economic conditions, try to gaslight constituents into legitimizing the sitting vice president with clout and cultural capital, as she presided over the very global dysfunction that has us seeking comfort from one another’s bonnet sermons.

The end of neoliberalism is the end of the classic model of celebrity, wherein the talented, pretty or charismatic are appointed and worshiped as if by divine decree. What happens when people discover they were made to revere counterfeits? They reacquaint themselves with the faith itself.

I often write about the almost carceral restrictiveness of Black fame, and all fame, especially superstardom, which streamlines human beings into complicity with their own commodification, in exchange for wealth or a chance to make the art they love. These stars are constructs, often groomed from a young age, and it’s easy to turn the groomed into abusers and groomers themselves. Yes, fame is a form of oppression, a currency, a potential gift and punishment for excessive attention-seeking, which is often a need for real love, which fame isn’t. As we divest from its dated narratives and disinherit its archetypes, we need artists who are astute and skilled enough to invent new ones.

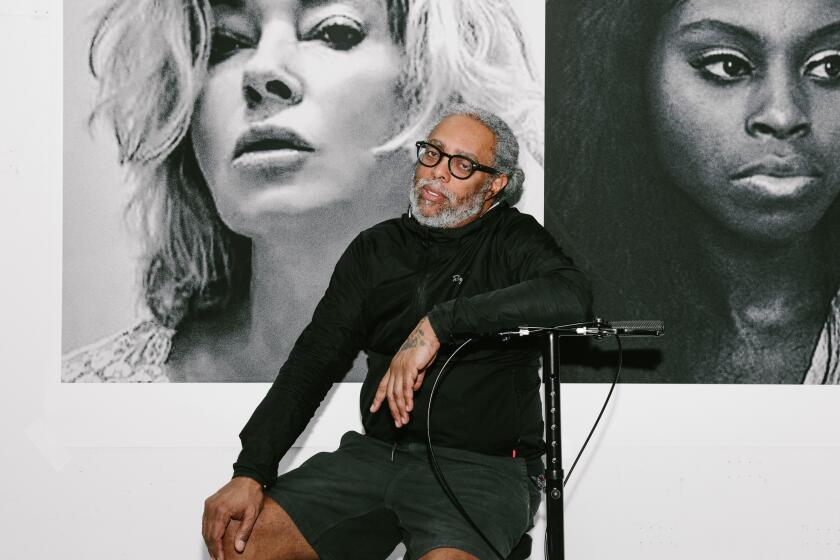

Nicole Miller is one of these artists. Her multimedia installations and films revolve around the ideas of performance: how we document it, how we witness it. Her work is at war with gossip and grift in favor of inventing paradigms and telling stories that force us to respect performers for what they give without defiling them for every flaw and private mishap. She films Alonzo King’s Lines Ballet dancers and describes the experience as more intense than a love affair, because their movements invent syntax beyond verbal language, enhance speech without deferring to it. Her most well-known work, “Michael in Black” (2018), presents a version of Michael Jackson so visually arresting it becomes shrine and resurrection simultaneously. She captures quiet reverence in someone so scrutinized he’s not permitted vulnerability. She demonstrates how the unspeakable or deliberately unspoken can be shown and performed and left at that.

Beyoncé is the most expensive ticket in the history of Black music. People might contemplate spending their rent money to see her live. People who could not access or afford Beyoncé tickets will go see the documentary.

In my conversation with Miller, we wonder: What might emerge in the place of the famous entertainer, the movie star, the heartthrob? What is the antidote to delirious spectacle, and are we lonely for it? Journalists in Gaza, girls at home in bonnets, men hiding in their cars to theorize about stocks and sex in dimly lit videos — everyday people who happen to have a camera phone might just be our new heroes. The collapse of what someone on X smugly called “the neoliberal global order” (“you’re gonna miss [it] when it’s gone,” she threatened) is a happy event on the horizon. People responded with images of predator drones, and Diddy in a “Vote or Die” shirt, assuring no one but deranged fanatics will miss it.

Harmony Holiday: What is this pattern wherein you can trade the currency of Black glamour to become an overt grifter, a clout chaser with no vocation but that — an “industry plant”?

Nicole Miller: I was thinking of this thing you said to A.J. [Arthur Jafa] during your talk, “I don’t have idols,” and I think that’s the solution, restore people to their humanity.

I love performers. That’s what my work is about: working with performers, being in awe of them. I don’t wanna kill off the performer, I don’t wanna turn away from the performer, but maybe if we let them exist in the context they’re really in ...

HH: Margo Jefferson writes about this in her 1973 Harper’s essay, “Ripping off Black Music” — Elvis being Chuck Berry in whiteface, which is a redundant way to be, and, while well done, is a violent, silent constant of Black life, which is this hypervigilance to what sells about ourselves, whether at auction or to a record label, or press, or a magazine. The keen and talented whites who can mimic this commodification of Blackness pull off a second abduction and enslavement in many ways.

But it also frees us because the thing we really want to make, no one wants to talk about or buy, and anyway, it isn’t for sale.

With two upcoming shows, one at Gladstone Gallery and another at 52 Walker, Jafa reflects on what it means to get a big break as an artist.

NM: As a filmmaker, it’s always a matter of people making space for your creative voice. So much of it becomes tied to getting the resources to make your work. And having any sort of feeling of desperation related to the production of artwork is so wrong, so counterintuitive to any creative practice.

HH: Can we discuss “Michael in Black,” one of your most widely circulated works? It’s a cast of Michael Jackson’s body, the only real replica that existed, that was purchased and auctioned. He’s genuflecting and appears penitent, it’s him with no public or private, shipwrecked in place in a way. His stillness screams and reveals so much anguish.

NM: He’s like an ideology that gets extended beyond our bodies. When you make work about him and you’re talking to a fan, it’s like you’re insulting them. And when you’re talking to a detractor who has renounced the cult of Michael inasmuch as it can be renounced, you’re also insulting them.

HH: The anxiety of and desire for his influence. So much of what I’m making now is insulting people’s idols and restoring antiheroes to glory, talking about the taboos that cannot be commodified, because there’s this cabal exploiting the currency of fame to brainwash in terrible directions, while making art that encourages that hypocrisy. And examining the death of this era of celebrity — which in my estimation has been about 50 years, from incipient to unraveling — is a way to mourn it openly, so it’s forced to finish dying. It’s been anemic for decades but refusing to collapse, like so many empires. Also, it’s a means of reviving what’s real.

NM: I mean, if we really get into it, all art exists to help us deal with death. And cinema, in all of its surface-ness and genre-ness and equations for reaching a satisfying ending, is always about feeling like we can contend with the ultimate ending. So, when you mess with that feeling of safety, with what satisfies through narrative-building and artwork, you’re messing with people’s relationship to death, their feeling they have a handle on it.

HH: That is so true, and so necessary for fundamental change, because we need new undertakers, new reapers. We can become the ones who intervene when we witness evil and tell it to go, or, if we’re brave, kill it off, spiritually not violently. Art lets us kill terrible menaces and keep our hands clean.

In 1968, the two men convened an impromptu ensemble that they knew might destabilized their reputations. The day they spent, exhausted together on the crossroads of here and gone, is the kind of convergence they make movies about, so we forget it really happened.

NM: Did you publish the essay that’s a letter to James Baldwin?

HH: Early next year it will come out.

NM: That’s that work, I think, bringing him back in a new form to address him and not as a fan. Using love for his humanity, which means you can never come at him with fanaticism.

HH: Is the end of celebrity the end of fanaticism?

NM: I think the development of AI is really going to re-situate everybody to this. It’s going to be so much more accessible for people to make more complicated kinds of work. And what I love about that essay, if we think about what a fan is — a healthier way to talk about experiencing other people’s work, and their voices, is being in collaboration with them as humans who are alive before or after. I hope technological advancements give more people the opportunity to be in conversation with the things that they love, an extension of that creativity, instead of just zombie consumers.

HH: Working with a lot of dead artists’ archives, including my father’s, early on I decided to reject the received reputation, the murmurs about him around L.A. as I was growing up, and just commune with him through his music and etheric presence, and let him change that way even in the afterlife. AI, with all its trappings, might help people gain similar agency and understand that events, hellos, goodbyes, aren’t so fixed, which goes back to why we’re in need of new approaches to narrative, because we no longer die into the same rituals.

NM: The more I get into different kinds of practices, I do think that artists channel. So, just feeling grateful to be alive at a time when we get someone like Alice Coltrane’s work, and not obsessing over them as an image or symbol, using it to channel and as a channel.

I also think, I’m a cinema lover, so I do love so many of the conventions of narrative storytelling, and the language that’s been built around how a western is told or how a horror story is told. There’s something about AI being this accumulative source that is like what genre is based on — moves we make to move forward based on looking back at how structures and language are built. I’m just excited for how weird that’s gonna get when you can just make moving images that look convincing. It’s reimagining the body.

[We see a ghost of passing lights, a shifting of some energy body in the room with us.]

If we really get into it, all art exists to help us deal with death. And cinema, in all of its surface-ness and genre-ness and equations for reaching a satisfying ending, is always about feeling like we can contend with the ultimate ending.

HH: We’ve conflated types and now we’re saying no more — just because there’s glamour attached to two people, and obscene wealth and hype, or prestige doesn’t mean they are the same. Kendrick, Drake, Malcolm, Fred Hampton, James Baldwin, M.L.K. — we love them all, but we want to let the wild cards shine as the molecular revolution they are so more of them can exist and it becomes normal. You said something interesting about Sigmund Freud’s writing, about all of his work being fiction. In a way we are called to do similar work with types, with the objective being to stop pathologizing the ones that might heal us or rescue us from neurosis.

NM: The first video I ever made was trying to make a video of a figure that was beyond identification, as an archetype or as a character. And when I first got into being a Black artist in the art world, I thought, maybe this is a context where there’s room to start doing that. Because while I love film and I love genre, I was totally dissatisfied by the question of ‘what is a Black character in any of this?’ And then I realized, wow, that’s actually freeing.

HH: It is. The received Black characters, those among the falling stars, are obfuscating their disgrace with the same language they use to dazzle, rap, sing. We can’t go on identifying with that. It’s forcing people to face where they are situated in class warfare — if your rich Black heroes who look like you can fall that far, how far do you fall when they go down, ‘cause you’ve worshiped them for so long? It didn’t work to use celebrities in the presidential campaign for that reason. No one wants to be associated.

NM: But even those people are addicted to being seen. I’m an artist, I want to be seen and known for the work I make, so there’s a way that celebrities are martyrs but also responsible for some of what happens to them for wanting to be seen.

HH: In my mind, there was a time when people weren’t fixated on that and focused on craft, but Black beauty is impossible to look away from. Miles turns his back and people obsess over his image, his looks. And then when we refused it, we were met with envy or theft (“cultural appropriation”), forced to be spectacle to maintain what’s ours.

NM: It’s such a complicated dance, to try to dismiss them as minstrels while also understanding the quality of their work. And that brings up handlers. The adjacent.

HH: As the stars fall their handlers and enablers become more visible, more implicated. They wanted to be seen as heroes, now they’re outed as agitators for a phony and sickly culture. And if we cut out the middle man, maybe our attention will naturally shift to healthier role models and stranger, more unmediated narratives. Maybe.