- Share via

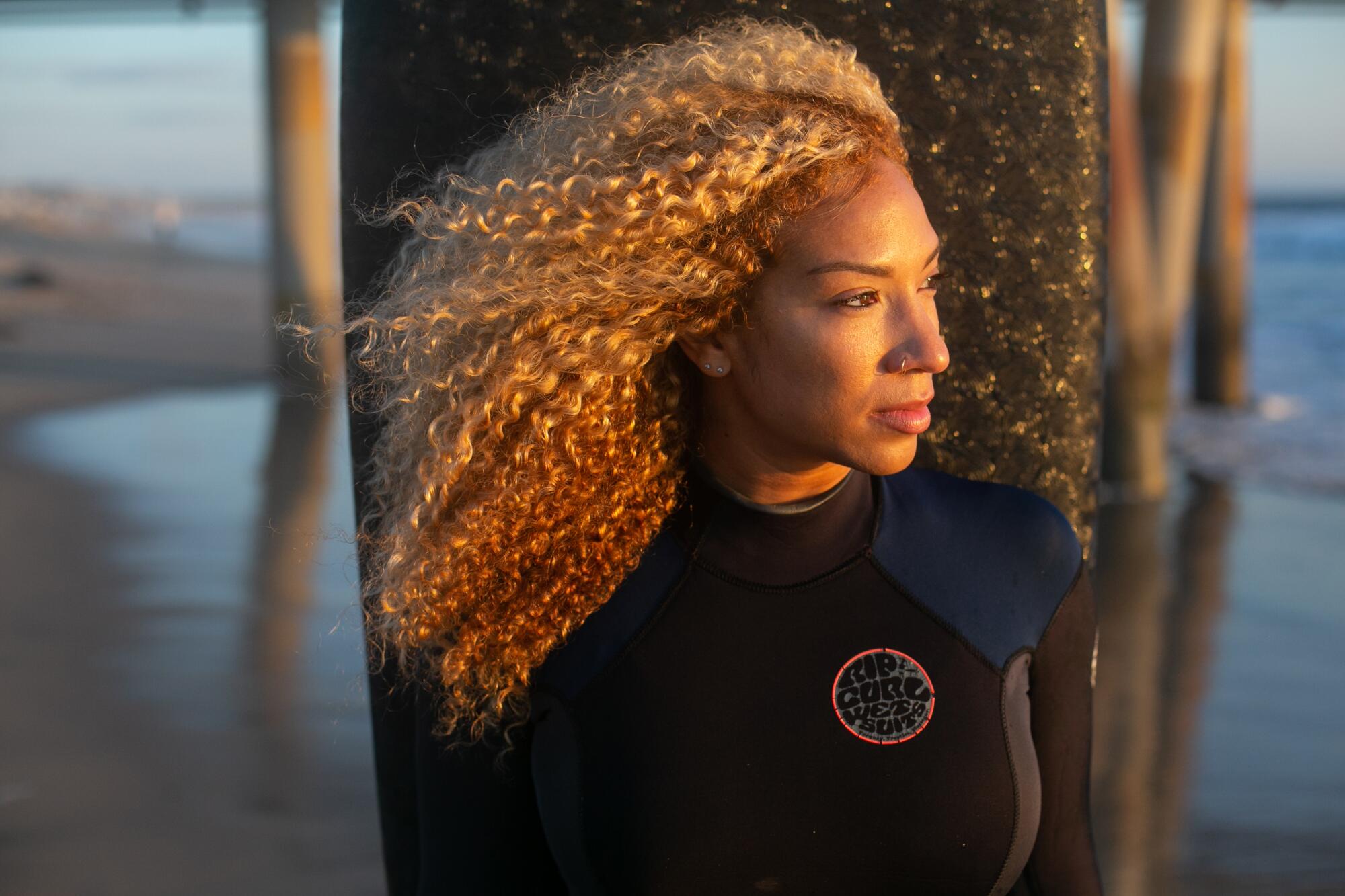

Ask a local surfer in Manhattan Beach about “the incident” on Presidents Day, and people will know exactly what you’re talking about. It started as a normal South Bay outing for Justin “Brick” Howze and Gage Crismond, two friends who have been regulars there since they started surfing together eight months ago. They made the trek from Hollywood. Did the dance of getting into their skintight wetsuits as the sun rose. Waxed their surfboards while blasting music in the parking lot.

The waves weren’t that great when Brick, a 24-year-old musician, producer, creative director and DJ, found himself in the middle of a couple of traffic collisions in the water. First, a surfer dropped in on Brick’s wave, resulting in Brick’s board thrashing the other surfer’s board. The second time, it was Brick who accidentally cut someone off. “Get the f— out of the way,” the surfer told Brick. An argument ensued.

Collisions and aggression are typical in surf culture, along with vague codes of conduct that vary from beach to beach. Manhattan Beach has a reputation for invoking the latter to justify the former, especially when it comes to surfers deemed by locals as outsiders; “localism,” as it is known, is the culture that surfers adhere to. Some say it’s surfers just being protective of their home turf. Others think it’s a guise for something more insidious. Dan Cobley, 42, who has been surfing in Manhattan Beach for 30 years, says localism reigns because of the quality of the waves.

“We’re in an unregulated sport, so we drop some rules [on sharing waves], which make a lot of sense,” he says. “But now they’re 100-plus-year-old rules.”

Graham Hamilton, L.A. chapter manager of the Surfrider Foundation and a surfer of 20 years, believes localism can be a veil for racism. “It’s rooted in this false sense of ownership,” he says. “Like, ‘I live on this block. This is my beach. If you don’t live here, get the f— out,’ you know?”

In L.A., groups like J-TOWN Action と Solidarity, Chinatown Community for Equitable Development (CCED) and KTown for Black Lives are organizing on Instagram.

As emotions climaxed, a different surfer — white and older — inserted himself into the fray. He began calling Brick the N-word repeatedly. Then he called him a “donkey” and violently splashed water in his face. He also called Gage, a 25-year-old dancer and choreographer with painted nails and arms full of scribbly tattoos, a gay slur and told him to “go back to the streets.”

“Go down there … that’s where the Blacks used to surf,” the man added, referencing Bruce’s Beach, a once-thriving Black-owned resort at the center of a fierce land battle in Manhattan Beach today. (The property was taken through eminent domain more than 100 years ago. Local activists are calling for Los Angeles County to return the land to the living descendants of the Bruce family and for the city of Manhattan Beach to publicly apologize and provide restitution for its role in institutionalized racism.)

As the altercation ensued, a crowd of mostly white surfers surrounded Brick and Gage and refused to intervene. A Black passerby named Rashidi Kafele took notice and started filming. He wasn’t used to seeing Black surfers in the water and, upon hearing the N-word, knew he had to document it.

This was the first time Brick and Gage had been involved in a racially charged altercation in the water, but locals had seen instances like this before. Kavon Ward, founder of the organization Justice for Bruce’s Beach, says the situation “shows that nothing has changed in Manhattan Beach.”

“I know a lot of Black people that I’ve talked to feel the same way,” she says. “When they come into Manhattan Beach, there’s this air of, like, they just don’t belong or they’re not wanted. And it’s unfortunate that the residents of Manhattan Beach don’t see that. They don’t notice that.”

Jessa Williams, another beginner Black surfer, says that in December she was called the N-word multiple times in the water at El Porto, one mile north of the Manhattan Beach Pier. “I felt almost re-triggered since it happened with Brick and Gage,” she says.

In the moment, Brick retreated into a meditative state. “I was just aware of my surroundings, and aware of who I am, and aware of what this moment actually is and what this moment actually means,” he said later on Instagram. The easy reaction would have been to punch the guy in the mouth, Brick said. “But do you want to be exactly what they want you to be in that moment?”

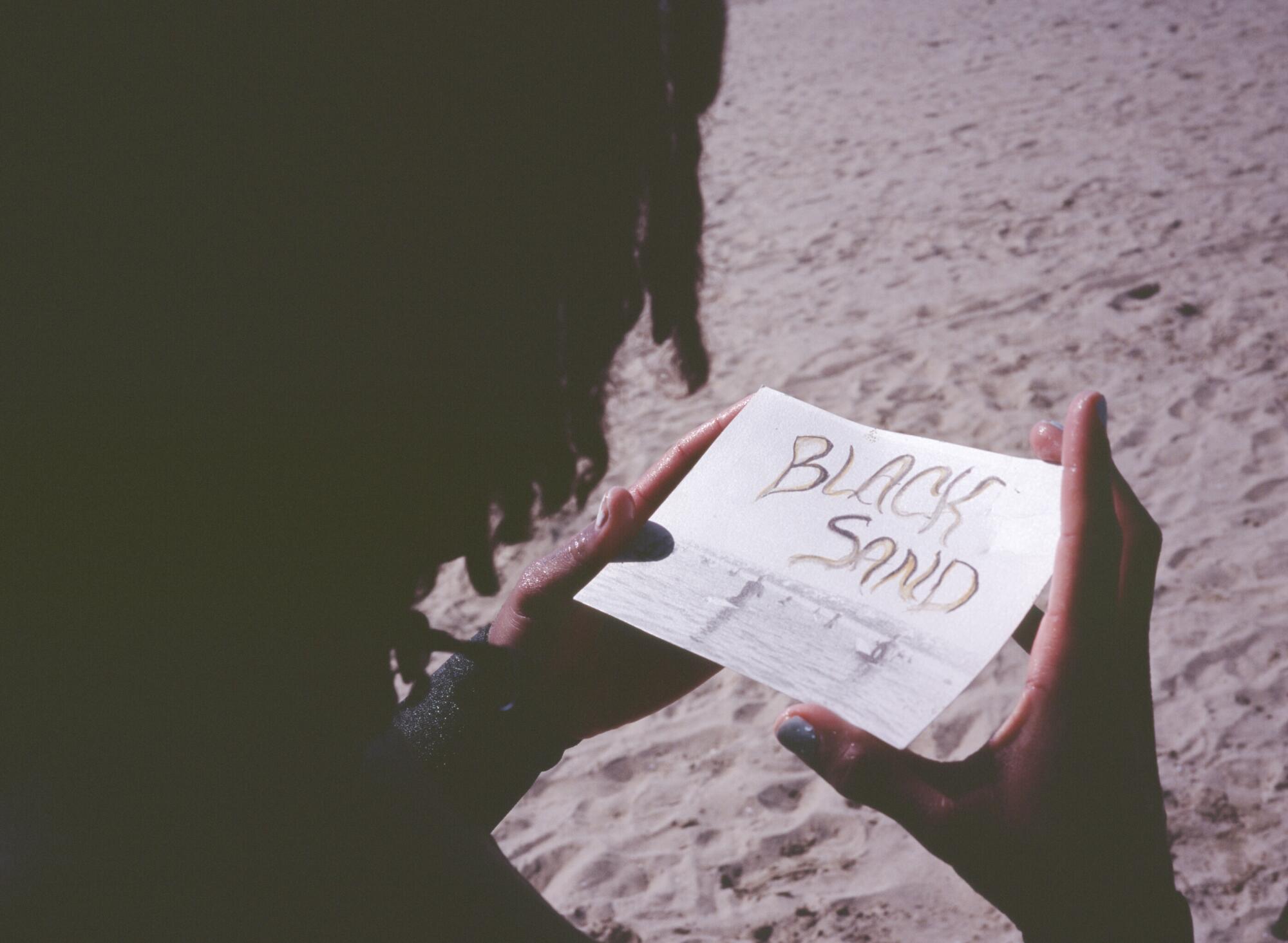

Later that day, Brick and Gage went on Instagram Live for 37 minutes, broadcasting to Brick’s 76,000 followers. Brick recounted the morning in detail, while Gage rolled a joint and filled in the blanks. They also posted the images captured by Kafele of the surfer splashing Brick in the face to the Black Sand Instagram account, a surf and arts collective they started in October. The posts got the attention of organizations including 1 Planet One People, which advocates for inclusivity in surfing and encouraged the friends to create a call to action.

Paddling for peace

Brick and Gage wanted to “reset the tone.” They knew that last summer, after the killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Ahmaud Arbery, surfers organized “paddle-outs” in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement. Traditionally, surfers paddle out a few yards from shore and join hands in a circle to memorialize someone from their community who has died. Brick and Gage thought that the paddling out was a powerful gesture. And, if they did it on the same stretch of Manhattan Beach where Brick was called the N-word, it had the potential to make a statement. They blasted it out on their Instagrams.

Historian Alison Rose Jefferson takes us on a tour of what remains of Santa Monica’s once tight-knit Black community, decimated by racist policies.

On Feb. 21, 200 surfers showed up, along with camera crews, journalists and observers from the pier. Many surfers who attended the Peace Paddle said it was the freest they’d ever felt in the water, despite it being too crowded for anyone to catch a solid wave without collisions.

“It was really just about Black joy,” says Danielle Black Lyons, co-founder of 1 Planet One People, a collective supporting climate action and racial and social equality, and Textured Waves, which aims to boost participation among women of color in surfing. “That was the focus of the day: being around your people, being free to be whoever you are and surf your face off without worrying about if you were going to make some white guy angry for accidentally dropping in.”

After the Peace Paddle, the South Bay’s Easy Reader newspaper published a story about the events. The headline, “Localism at the Manhattan Beach pier triggers racial reckoning for surfers,” struck a lot of the Peace Paddle participants as problematic — an echo of the root cause of “the incident.”

“The toxicity of localism is heightened and enhanced and exacerbated when race comes into play,” Hamilton says.

Many surfers of color have a story like this.

Bobby Kim, the Asian American co-owner of streetwear brand the Hundreds, remembers a run-in while surfing in Santa Monica that escalated from territorialism to racism. “It’s that subtle nuance that people of color and minorities understand,” he says.

There are other nuances too, including misogyny.

“I’m not trying to take anything away from terrible, racist things happening to men,” says Williams, a Black woman who was surfing with members of Color the Water, a group offering free surf lessons to BIPOC, when she was called a racial slur by a white man. “They have their own unique layer of danger and vulnerability, but what I think is hard for people to remember is that when something like that happens to a woman, it’s not just about feeling angry, or humiliated, or disrespected. I was afraid.”

Avon has high hopes for its Koreatown studio and new vegan skin-care products. Will they attract a new generation of beauty shoppers?

‘The most free I’ve ever felt’

When Brick and Gage started surfing last year, they knew about the lack of representation in surf culture. But it wasn’t top of mind — at least not at first.

“I was just going for the ocean,” Brick says.

When it became clear that their new hobby wasn’t historically friendly to people who looked like them, they were already in too deep to be deterred.

“I made a promise to myself early on,” Brick says. “I’m not going to care what anybody out here thinks about what I’m doing and how I’m doing it. I’m not here to impress anybody. This is my disconnect from the world that I know. So I’m not going to come over to this world and get all self-conscious.”

In the water, everything else just became noise.

“I felt the most free I’ve ever felt,” Gage describes. “It’s almost like magic. You always think about the oceans and how we don’t know too much and how the moon controls the tides, but you never really immerse yourself in it. And then when you’re sitting in it, and you’re forced to think that this is a whole different world upside down … it’s kind of artistic. There’s no way to just say you’re an athlete; surfing is more of a spiritual thing.”

For Brick, “surfing is like that feeling when you get a check — some extra money,” he says. “Now imagine if you had control over that feeling and you could make that happen every day. Surfing pays your soul.”

The surfing lifestyle comes down to routine. On a typical day, unless it’s raining or the wave report isn’t good, the two men wake up before dawn and make the trek to the coast to surf for a few hours. Afterward, they’ll grab coffee and breakfast. Brick is a foodie and has been dragging Gage to Gjusta in Venice lately for a post-surf meal. Then they work on projects for Black Sand, the collective they started with their friend Tre’lan Tillman, a Black surfer who lives on Kauai. They’re usually in bed by 10 p.m. and do the entire thing over again the next day. The commitment is real: Brick even stopped taking meetings in the morning unless they were on the Westside and were scheduled for after he surfed.

Brick, who is from L.A., took up surfing in August. He was sitting at the beach alone one day and bought a $10 boogie board off a vendor out of sheer boredom. There was something about being in the water past the break while still being supported by a tangible object. He was hooked; he wanted to feel that sense of both weightlessness and security again. The next day, he borrowed a surfboard from a friend, bought a wetsuit on OfferUp and took to the water alone.

Image is the L.A. Times’ new style magazine, a celebration of Los Angeles creatives and intellectuals

Gage, who is from Holly, Mich., had never even gone swimming in the ocean before he started surfing last summer. He was searching for something much more than a hobby. In retrospect, he says, he was searching for an anchor in a turbulent time. He moved to L.A. two years ago to pursue his dance career, and then the pandemic hit with a double whammy: He lost all his dance jobs and went through a devastating breakup with his then-fiancée.

When he rented his first wetsuit and board in Venice late last summer, he had been living in his car for almost five months, parking near the ocean every night and surfing a couple of times a week on his own. It was only a few weeks before contacting Brick that he’d found housing again.

“Not even to be cheesy like, ‘Surfing saved my life,’ but I mean it kind of did,” says Gage.

Individually, Brick and Gage noticed the weird glances they’d get from non-Black surfers in the water. Brick describes paddling into the lineup while Black as “wearing basketball shorts to a nice restaurant.”

But a direct message on Instagram would change that. When Brick posted a photo of himself with a surfboard, Gage responded unsolicited.

“Bro, hell yeah,” read the message from Gage. “Let me know when y’all go out again. I surf too — and no n— surf ...”

They’ve been surfing together almost every day since, which has brought a sense of security and humor to an otherwise uncomfortable situation. It almost feels like a secret club.

“We were just on this idea of just making sure that we were creating our own space,” Gage says, “our own lane in surf, because that’s just naturally what we do with everything.”

From surfers to activists

Before the Peace Paddle, the friends didn’t think of themselves as activists. They were just two Black dudes trying to surf and make art.

Their place in the water means more now, Brick says. “You don’t really have the option to [say] ‘I’m not an activist’ in this type of a moment. … Yes, you are. If you thought that was wrong, and there’s a solution to it that needs to be found — yes, you have a responsibility.

“That’s where we stand right now.”

Since the Peace Paddle, people have asked: “What’s next?”

For Brick, that’s like being asked, while lying on the ground after getting hit by a car, where the nearest hospital is. “Like you are supposed to be figuring that out right now!”

Brick and Gage are currently more concerned with getting people to join Black Sand — their effort to encourage people of color to thrive in spaces where they’ve been historically underrepresented. They recently released a Peace Paddle capsule collection of T-shirts and crewnecks and are donating proceeds to local surf organizations and Bruce’s Beach activists.

“Its purpose and goal now,” Brick says, “is just increased visibility for people like us in the water and to inspire others who have just tried to be different in spaces that they may not have previously felt comfortable in.”

Both Brick and Gage want to move to Manhattan Beach. They’ve been religiously sharing the work of Justice for Bruce’s Beach on Instagram, and digging into the town’s racist history. Brick has his sights set on finding the perfect spot near the water. He’s been scanning Zillow listings for two months.

Sure, Black people make up less than 1% of the population there. “I’ll become 151 of the 150 black people that live there right now,” he says. It’s more like 191. Brick hopes even more will catch the wave.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.