- Share via

This story is part of L.A. — We. See. You!, the second issue of Image, which explores various ways of seeing the city for what it is. See the full package here.

Designer Brenda Equihua’s references growing up in a working-class Mexican household in Santa Barbara exuded an over-the-top flashiness: Doilies under the VCR. Organza ruffle curtains. Cloth toilet-seat covers with matching rugs. Fake flowers in those glass cases you’d get at the swap meet. Her mom, whose aesthetic was similar to the glamorous Mexican movie star María Félix. And something else: San Marcos cobijas.

After Equiha graduated from Parsons School of Design and spent years of working as a luxury women’s wear designer for places like Monique Lhuillier, Tadashi Shoji, Juan Carlos Obando and her own namesake label, these references got buried. Equihua spent months trying to coax them out again when one day it hit her: cobijas, but make them coats. The idea felt fresh and old. New and nostalgic. Like a gift.

Equihua is the kind of person who in real life is as you’d imagine she’d be based on her online presence. She’s warm and funny and kind of zany, thinking her thoughts out loud the same way she types them out in captions. She does a running series of lollipop reviews on her Instagram and has an ongoing bit where she puts miniature cobija sweatpants and shoes on her index and middle fingers to mimic breakdancing. But when she talks about the inspiration behind her cobija outerwear, she becomes very earnest. “This came from outside of me and it’s so beautiful and I have to honor this story,” she says.

The designer has since done the same with other classic materials from the culture, including colorful, waterproof manteles with tropical flowers you might find under the jugs of agua fresca at taco stands across L.A., which she utilized in her Paniolo collection released early last year. It honors the legacy of the paniolo, or Hawaiian cowboy — a result of the cultural exchange between Mexican vaqueros sent to the island to teach the natives who lived there to herd cattle in the 1700s. Her next release, coming out this summer, is a collection of interchangeable sets inspired by the paniolo pattern and others that hark back to her beginnings as an evening wear designer.

But it’s the cobija coats — lush, colorful and warm, making you feel like a walking Latinx teddy bear — that remain her most beloved pieces to date. “It’s coming from a place that’s being informed by experiences,” Equihua says.

A brief — and incomplete — history is in order:

Image stories

Darian Symoné Harvin talks to Lauren London about Nipsey Hussle, acting, and how seeking truth is an act of love

We wanted to know about the real L.A. So we asked our favorite Angelenos to show us

Ismail Muhummad meditates on how Noah Purifoy imagined a future where people aren’t discarded

E. Tammy Kim talks to the activists who have the antidote for the erasure of East L.A.

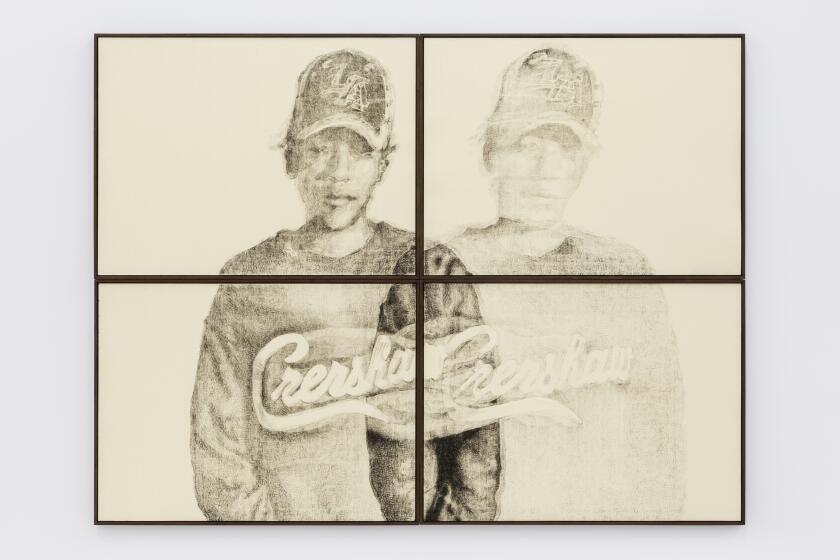

Ian F. Blair talks to Kenturah Davis about language and the tradition of Black art from the foothills to South L.A.

1. Aguascalientes, mid-1970s. A man named Jesus Rivera Franco dreamed of keeping Mexican families warm. He made serapes and scarfs, shawls and blankets. But there was something about that last one — the cobija — that he fixated on. His brother, Francisco Rivera, decades later told an L.A. Times reporter: “His dream was to come up with one that would last, that every Mexican would love.”

2. The lore of the San Marcos cobija is in Equihua’s DNA. She remembers sleeping under the weight of them while growing up in her Santa Barbara home, and the time one of her family members wrote them off as tacky. Equihua saw them differently; to her, cobijas represented a mother’s love.

3. One of the first acts of love my mother showed me was buying a mini-sized, original San Marcos cobija as my baby blanket in 1995. She still has it saved in her garage. It’s a faded yellow and white, with images that include a moon, stars and a bunny wearing a hat. I learned to crawl on it. It kept me protected on the grass while playing at the park. My mother draped it over my stroller when I was sleeping, to protect me from the sun. When I moved out on my own for the first time at 18, it was the family cobija — a rich royal blue with an image of a golden sun and moon eclipsing one another — that I took with me, tattered edges and all. It brought life to an otherwise bare apartment. It smelled like home.

4. In 2017, Equihua was in the back seat of a van driving to Six Flags with her family when an unfamiliar voice spoke to her. “It was like a spirit or something put it in my mind,” she remembers. Immediately, she told her brother to turn the music down. She had a “crazy announcement” to make. “I told them, ‘I’m going to make outerwear out of cobijas.’” There was dead silence. “Nobody was like, ‘Yo, that’s fire.’ Nobody was tripping out.” But when Equihua released her New Classics collection in 2018, the reaction from the rest of the world was decidedly different.

5. Queen-size cobijas hang at the entrance of Global Linen Inc., one of the many blanket, comforter, carpet, curtain and sheet importers on Los Angeles Street in downtown L.A. Lush red roses, a black-and-white image of Marilyn Monroe smiling, the L.A. Lakers logo, a twin-size featuring Baby Yoda.

On Avenida Revolución in Tijuana, there are storefronts selling cobijas as far as the eye can see: Virgin Marys, zebras, homages to the Raiders, Chargers, 49ers. It was there, in the mid-2000s, that a vendor informed my mom and me that the original San Marcos cobijas were no longer in production; the ones being sold now were imitations made in Asia. “They’re not the same,” he said. But they still sparked instant recognition; they were still beautiful.

6. At the Tijuana border, cobijas are sold to people sitting in their cars in a queue. Vendors also are selling piggy banks in the shape of Jesus and the Virgin Mary, as well as raspados, elotes, diablitos and tejuino.

7. The Equihua Devotion coat ($720) is a deep burgundy piece that grazes the ankles and features an image of La Virgen de Guadalupe on its back. The Tigers of the North, a cropped bomber jacket ($580), shows a menacing gold tiger peeking through green leaves. (It is named after the norteño band Los Tigres del Norte.) There are also hoop earrings and scrunchies made out of cobija scraps.

Lauren London reflects on acting, Nipsey Hussle, Black L.A.

8. “They’re loud in color and loud and imagery, but they’re actually neutral in our environment,” Equihua says. “They’re only loud when it’s presented to the outside world. If you go into a Latino house, there’s a lot of stuff that resembles these types of elements.”

9. A woman in Boyle Heights told the L.A. Times cobijas were her parents’ “gesture of love.”

10. The religious symbols and fantastical, majestic animals watch over you as you sleep. They’re campy, maximalist, extra. For a younger generation of Latinx people, their coolness is almost ironic.

11. A meme-fied image of Homer Simpson cuddling in a black-and-white cobija with tigers on it; the words “every Hispanic in the winter” bannered across the top.

“I thought, either people are going to f— with it and they’re going to be like, ‘wow this is super fire,’ or it’s going to become a meme,” Equihua says about her work. Both things happened.

In 2019, the @rice_frijoles account on Instagram created a meme with one of Equihua’s press images from the New Classics collection — the words “Name a more representative outfit for both Asians & Latinos…I’ll wait” ran across the white space at the top.

12. When Equihua, the label, launched in 2016, the designer was making eveningwear inspired by her mom, Ofelia, who immigrated from San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, and raised Equihua and her siblings on her own. Ofelia died in 2013. Equihua remembers her as the kind of person who wore rings on every finger, always had her hair, nails and makeup done, and smelled like perfume when you hugged her.

“She was very regal,” Equihua remembers of her mom. “I think she used any opportunity that she could to dress up, especially because we were a working-class family. She never wanted that to be the reason that we were looked down upon by society, you know?”

13. Equihua told Vogue in 2018 the cobija “represents family and love and comfort, and it has very strong ties to Latino identity.” Her coats have channeled its broader appeal. Lil Nas X rocked Equihua’s Pray for Em jacket and Shrine T-shirt, both featuring an image of the Virgin Mary, during an interview with Zane Lowe. Lil Yachty stopped by Equihua’s booth at ComplexCon in 2019 and copped her latest pieces. Young Thug, in a picture with Meek Mill, wore the Devotion coat. “When I’m building a piece, I don’t just want you to put it on and feel a sense of familiarity with it,” Equihua says. “I also want you to feel like you’re discovering something else about it.”

14. “It was this thing of like, poverty but we’re still fancy,” explains Mexican poet and activist Yosimar Reyes. He grew up without central heating in eastside San Jose. “Poor people do not like to look poor, honey; we like to show out. I think that’s become the symbolism of these very decadent cobijas. We like the flashy as a symbol of our aspirations.”

15. “I was thinking, ‘Hey, maybe this is what it felt like when Ralph Lauren launched the polo,’” Equihua says of her cobija coats. “I launched a classic. This is a classic.”

16. “Yosi con Abuelita,” 2021. Acrylic on adobe. 72 by 57 by 1½ inches. Featured in his April show at Commonwealth and Council, artist rafa esparza paints Reyes standing behind his grandmother while he drapes his Equihua cobija jacket around her shoulders.

17. Princess Nokia, Paris Fashion Week 2018, wearing Equihua’s Pray for Em jacket.

18. Four of Equihua’s coats feature a Catholic saint on the back: “For some people it’s not even religious, it’s nostalgic. It’s not even about La Virgen, it’s about their mom,” she says.

19. “I don’t see me wearing this to church, but I mean, that would be cute?” — Yosimar Reyes, who owns Equihua’s Pray for Em jacket, among other pieces.

20. Like the original San Marcos cobijas (and the knockoffs that came after), Equihua sees her pieces as heirlooms to be passed down from generation to generation. “The idea of the heirloom comes from love,” she told Vogue.