- Share via

This story is part of L.A. — We. See. You!, the second issue of Image, which explores various ways of seeing the city for what it is. See the full package here.

The Eastside is constantly at risk of disappearing: sliced up and bulldozed over, redrawn, rezoned and marketed anew. But its partisans — Chicano and Nisei, Black and Jewish, Anglo and gentrified — practice a near-religious devotion to the neighborhood.

Sesshu Foster and Arturo Romo have spent decades mapping and resurfacing their native East L.A. Foster, a 64-year-old Japanese American poet, and Romo, a 41-year-old Chicano visual artist, are veteran public school teachers (Foster just retired) and union and community activists who know all the local murals and mariachis. Real and imagined Eastsiders fill Foster’s many books, from the novel “Atomik Aztex” to his latest poetry volume, “City of the Future.”

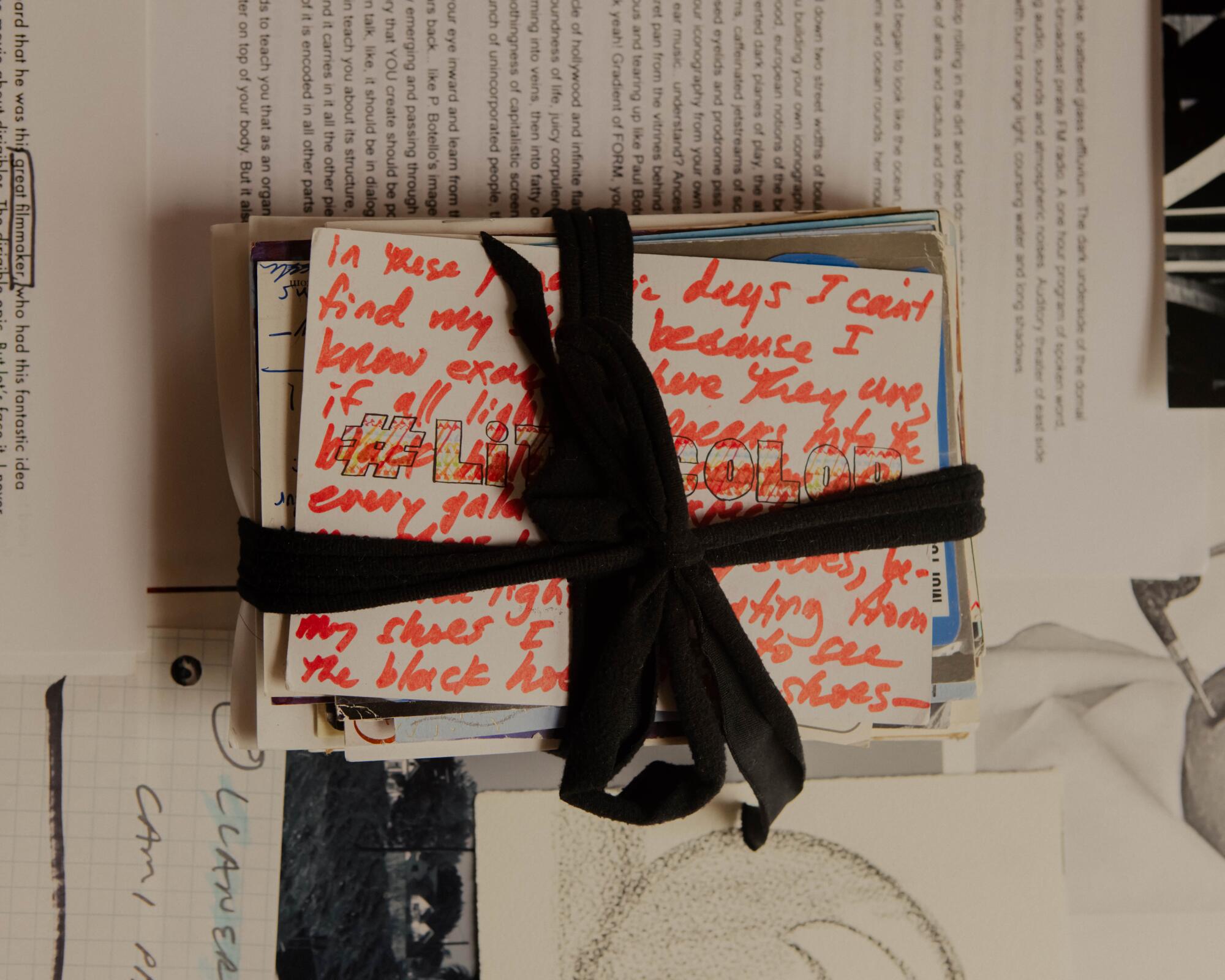

Now, Foster and Romo’s long-running collaboration — a living archive of text, image, walking and performance — has taken the form of a book. “ELADATL: A History of the East Los Angeles Dirigible Air Transport Lines” (City Lights, April 2021) explores our early 20th century obsession with blimps and utopian flight. Pronounced the Nahuatl way, with the final “l” chopped off, “ELADATL” is a multigenre book of fantastical adventure stories, imagistic biographies and invented archives — what the authors call “an actual history of a fictional company.” An antidote to erasure.

//

ETK: Both of you have long familial roots in East L.A. How far back do your families go in the area, and what’s the magic of the area? What makes you stay?

AR: My great-grandparents landed in Lincoln Heights from Sonora — that’s on my father’s side. And then my mom’s side, I am fifth-generation from Chihuahua, but they spent most of their time in Wilmington and in the port area of Los Angeles.

More from issue 2 of Image

Darian Symoné Harvin talks to Lauren London about Nipsey Hussle, acting, and how seeking truth is an act of love

We wanted to know about the real L.A. So we asked our favorite Angelenos to show us

Ismail Muhummad meditates on how Noah Purifoy imagined a future where people aren’t discarded

Julissa James profiles the L.A. designer who remade the Cobija into luxury fashion

Ian F. Blair talks to Kenturah Davis about language and the tradition of Black art from the foothills to South L.A.

SF: My aunt and uncle met at the Fellowship House by Evergreen Cemetery, and that’s why I ended up in East L.A. After the internment camps of World War II were dispersed, after the people in them were given $25 and a bus ticket and told, “OK, go wherever you want to, wherever your dreams take you.” The Fellowship House, a block north on Evergreen from Evergreen Cemetery, was a big, three-story tenement apartment building with bathrooms at the end of the hall — with little, often windowless rooms where the Nisei could stay for $30 a month, cook their own food, take a shower in cement shower stalls in the basement. That’s why I ended up in City Terrace — because when my parents violently split up, my aunt and uncle took us in.

ETK: I first met you guys in 2015. When you took me on your walking tours, which you’d posted to a website called ELA Guide, I learned about the real, concrete history of the area. At what point did you start melding fictional history with the existing history?

AR: It’s always been a part of my work, and when I first read Sesshu’s first book, “City Terrace Field Manual,” I took it as poetry, not necessarily as a document of reality or a document of nonfiction, whatever that means. But it came from a real place. My impulse as an artist, with East L.A. or with Northeast L.A., where I live, has always been to feed back into a place. One way to belong to a place rather than capture it or extract from it is to bring your whole self to it, your whole artistic self, and that necessitates some more expansive version of documentation.

ETK: I see what you do as historical salvage and re-creation. You’re responding to historical erasure, whether by developers or state violence or new forces of hyper-gentrification. Is this particular to East Los Angeles, or could it apply to any other neighborhood?

SF: As a writer, I’m dealing in nouns and verbs and adjectives, and for both me and my students, we know the names of iPads and iPhones, and TikTok and YouTube, and we know the names of stores, we know the names of streets, we know the names of cities and so on and so forth. But we could be standing next to a tree that we don’t know the name of. The erasure is not only that they erased the Tongva from Los Angeles and left only a few names like Cucamonga or Tujunga. Other things block our appreciation and understanding of the actuality of the trees, of the plants, of the place. And I think that happens everywhere. Everywhere that’s colonized.

ETK: All this thinking and walking and artmaking you’ve done over the years gives “ELADATL” the feeling of an ongoing catalog. What was your process of going through your archives to build out the book?

SF: Our collaboration was not merely intellectual; it was also physically driving around East L.A., looking at historical sites for the ELA Guide, investigating odd things that we found. We were going through the neighborhood, finding people to interview and talk to. Some of the characters in “ELADATL” — for example, Juan Fish comes from a garage truck we kept seeing around the neighborhood. We knew that the garage no longer existed but the truck was prevalent in the neighborhood. And the Virgin Defacer: Many storefronts have a Virgin of Guadalupe painted for safety purposes or mystical purposes to protect their business, and this guy, this Virgin Defacer, was going around graffitiing over their faces. So all these — what would you call them? Neighborhood personalities? Or spirits that kind of inhabit interstices or secret spaces?

How Equihua cobijas became jackets for Lil Nas X, Young Thug

ETK: In your invocation of Native history, including the title of the book, “ELADATL,” a nod to Nahuatl, you’re thinking about both the Indigenous claims to the land and ecology. How do you relate to the natural environment in a place where there’s a lot of concrete, where people are not necessarily exposed to “nature” all the time?

AR: I’m looking out the window, and I see that my neighbors have this garden, and it’s filled with sugarcane, beans, all kinds of squash. In my neighborhood, people endure, break up the concrete and plant gardens for food — ancestral foods. That happens all over Lincoln Heights, all over East L.A. And, my cousin Reies Flores is another inspiration in the book.

SF: The chicken man.

ETK: I was going to say, the urban-chicken-farming chapter, “Chicken Man.”

AR: He appears a few times in the book but he’s also an educator, and the scope of his education is to decolonize students’ minds around environmental issues. When they go home, they’re going home to chickens, backyard chickens, and gardens, and they know the names of plants but somehow, they’re told that to be an environmentalist or to be progressive on the environment means to drive a Prius. The ecological impulse is to recognize that a place like East L.A. is already practicing all these things. The spirit of the book is one of enduring. The dirigible company rises up and then gets destroyed, and then it rises up again and gets destroyed.

ETK: Did the original concept of the dirigible come out of your research on Bessie Coleman, the pilot who did stunt flights in L.A. and inspired Black aero clubs?

SF: It was simply an obvious symbol for the failures of the 20th century — the many, many interesting utopian projects that blew up in one way or another. So it came before I knew about the Bessie Coleman Aero Club. It came before we discovered that pilot instructor James Banning, who was part of the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, was buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

AR: The concept of the dirigible started as a joke that Sesshu was riffing off. That’s our process, not only driving around East L.A., identifying, asking people, taking photos, remembering histories, but also a lot of talking about the true histories of places, some of which are so heavy that to continue on, you just laugh.

ETK: In the world that you guys have constructed, and that’s now instantiated in the book, even though it’s a history, there’s a timelessness to it. To what extent is “ELADTL” a guidebook for Angelenos of the future?

SF: We live in the town of Hollywood that projects its imagination across the planet, colonizing everybody’s minds with Marvel movies, violent vigilante movies, revenge thrillers. We want people to consider other realities, alternate realities, other possibilities. William Powell’s book “Black Wings” and the Bessie Coleman Aero Club, those were both imaginary but they were also real. They were real dreams that those people had about uplifting masses of people out of oppression.

AR: I was just listening to an interview with Jared Loggins, a political theorist, who mentions the importance of “coming up with different ancestors.” We need new ancestors, because the ones that we’re taught to emulate are not the right ones for us, and I think the book is kind of about that too. Recasting a history so it includes people like us is part of the way we’ve built a different, more liberating imagination.

ETK: What terminologies do you use to define those ancestors? We’re in a period where a lot of our racial assumptions and identity terms are in flux, and your project — and the part of L.A. that you’re in — proposes something beyond the racial binary. Let’s take the term “Chicano,” for instance, which I know you’ve both thought a lot about.

AR: I identify as Chicano, with all its complexities. The feminist writer Cherríe Moraga has this whole take on “Latinx” and “Chicanx,” saying that each generation’s identity is tied to the place from which it came, which I think is really accurate. I’m a little wary of solid identities. I like: “I’m neither from here nor there.” I think that gap is useful. It’s actually how my parents, as Chicano movement people, articulated their opposition to destruction and assimilation. I don’t think we should abandon it out of this idea that there’s a better identity.

SF: I grew up during the Chicano movement, and my understanding and feeling was that there was a recognition of the mestizaje, or the mix of Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas, that it wasn’t just Mexican. It was a polyphonic and unitary worldview that was very influential in my political thinking when I was coming up. Our work owes something to Asco, the Chicano performance group that was directly related to the student walkouts of ’68 and who were active from the ’60s through the ’70s and whose work only in the 21st century has become recognized as lasting and important. Harry Gamboa, Gronk, Patssi Valdez and Willie Herrón III — those guys were models for me when I was growing up.

ETK: There’s been so much Eastside organizing around land, food and art in recent years. Which activist groups are you involved with these days?

AR: I’m a member of North East L.A. Alliance, an antigentrification group out of Northeast L.A. that’s been trained to understand gentrification and the impacts it has on communities, but that’s also built a really beautiful community around artmaking. What we do is, we try to see gentrification through the lens of ongoing colonization, so we do engage in some property-rights activism and around rent control, but we’re really focused on reframing narratives around land and land use and the ultimate sacredness of land — the right for people to have place, belonging and shelter. For instance, there’s the USC biotech corridor — that might be something we offer a teach-in on.

SF: In the past pandemic year, I distributed food through the El Sereno People’s Pantry. I picked up food donations and handed out food boxes on Alhambra Road with the organizers on their Sunday giveaways a few blocks from my house. The line was mostly moms with families and the elderly driving up in beat-up cars, with a couple homeless guys off the avenues.

ETK: The last time I saw you guys was in 2019, when I was reporting on the United Teachers Los Angeles strike and you were both on the picket line. Sesshu, you’ve since retired, but Arturo, are you still active in the union, and how have your students fared during the pandemic?

AR: Overall, I think we emerged from the strike having a lot of momentum and having changed a big part of the conversation in a way that only a mass movement can do. We changed the public discourse on privatization and charters, and I think the strike also instilled a lot of fortitude — pride in being a worker, in being an educator.

My students are experiencing a crisis layered on top of three crises. The pandemic is one crisis on top of ongoing economic exploitation, gentrification and housing scarcity. Some of my students are homeless. Many are housing insecure. Many had to take on jobs during the pandemic and then faced family death and illness. An organized labor force like us, we were able to call that out. Without UTLA, the strike, and our presence as a giant union, we wouldn’t have the safety protocols we do now, which was what students need. These are children. It was asking the state and federal governments to reorient around children. The money’s there; we know the money’s there. It requires a strong, organized labor force to make those demands clear.

E. Tammy Kim is a freelance reporter and essayist and a contributing opinion writer at the New York Times.