- Share via

One day when she was 12 years old, Barbara “Sky” Burrell, owner of Sky’s Gourmet Tacos on Pico Boulevard, saw a neon, taco-shaped sign in the window of a local restaurant in the town where she grew up. The glowing image, in Waukegan, Ill., outside Chicago, captured her curiosity. She begged her mom to take her for a visit.

All these years later, Burrell remembers every detail of that taco. “It was horrible,” she says, laughing.

She guesses that it was a beef taco, but “I would have never known it. It was very mushy and had no taste — it didn’t even have salt and pepper.”

A crispy fried tortilla was the taco’s saving grace. A young Burrell coated it in hot sauce.

“Between the hot sauce and the shell, we had a number going there,” Burrell says.

While she had no desire to make another visit to that particular taco shop in Waukegan, she insists that “something snapped with that taco. I saw that I could do something with it.”

She and her mother drove across Chicago to a Latin market where they found corn tortillas, back then sold in a can. Burrell first experimented by heating the tortillas in the oven before one day frying them in a skillet with butter.

“I said, ‘Oh! This is just right,’” Burrell says. “After that, I became unafraid of it.”

No ingredient was off the table. Burrell would pluck avocados from her family’s backyard tree, scramble eggs with tomato or spoon baked potato on top. On Fridays, when her family observed the Catholic tradition of eating seafood, she made shrimp tacos.

With her mother and grandparents being from Georgia, she also took inspiration from Southern cuisine. Burrell would cook down pork neck bones, stripping the tender meat and crisping it up in the skillet before wrapping it in a tortilla.

“It was just like carnitas,” she says. “Delicious, OK?”

Burrell’s taco obsession only grew after relocating her family to Southern California in the 1970s. First settling in San Diego before moving to L.A. in 1975, every Saturday morning she’d head down to National City, where she watched tortillas made fresh by hand and was introduced to guacamole. “I didn’t realize then how much it was becoming a part of me, a staple in my life,” she says.

Barbara Burrell, owner of Sky’s Gourmet Tacos, at her restaurant.

Tacos and fixings from Sky’s Gourmet Tacos.

Burrell still remembers the day she had the idea to open her own taco stand: Jan. 23, 1992. She was nine months into unemployment after quitting her decade-long career in wealth management. The sizable savings she had left with were dwindling.

“I woke up one morning and said, ‘Tacos!’”

By February, she had secured a location on Pico Boulevard. On March 5, 1992, at 1:44 p.m., she opened Sky’s Gourmet Tacos, making tacos on a 24-inch Wolf stovetop, with just a handful of seats across the cozy interior and patio.

The menu featured just five tacos to start — chicken, ground turkey, ground beef, pinto bean and the shrimp taco that Burrell had been perfecting since adolescence. Generously doused in a sweet and tangy sauce, cooked in butter and wrapped in a corn tortilla that’s dipped in the same sauce before getting crisped on the grill, the shrimp taco quickly became the signature item.

“It was new, it was different — people lined up,” Burrell says.

What she didn’t know then was that she belonged to a pioneering class of Black chefs in L.A. Like her, many were trained in their home kitchens. Nevertheless, the still-growing group put their stamp on the taco, inducting it into California soul cuisine.

The moment was the birth of the Black taco.

On every birthday since I can remember, my mother, Donna Dorsey, has made my brothers and me the meal of our choice. Year to year, my answer never changes: tacos.

Over the years, the setting has changed: from our hilly home in the San Diego suburb of El Cajon to a two-story in Riverside’s La Sierra neighborhood to the Canyon Crest cul-de-sac near UC Riverside where my mom still lives today. In my memories and as I watch her make them before me now, the tacos are the same.

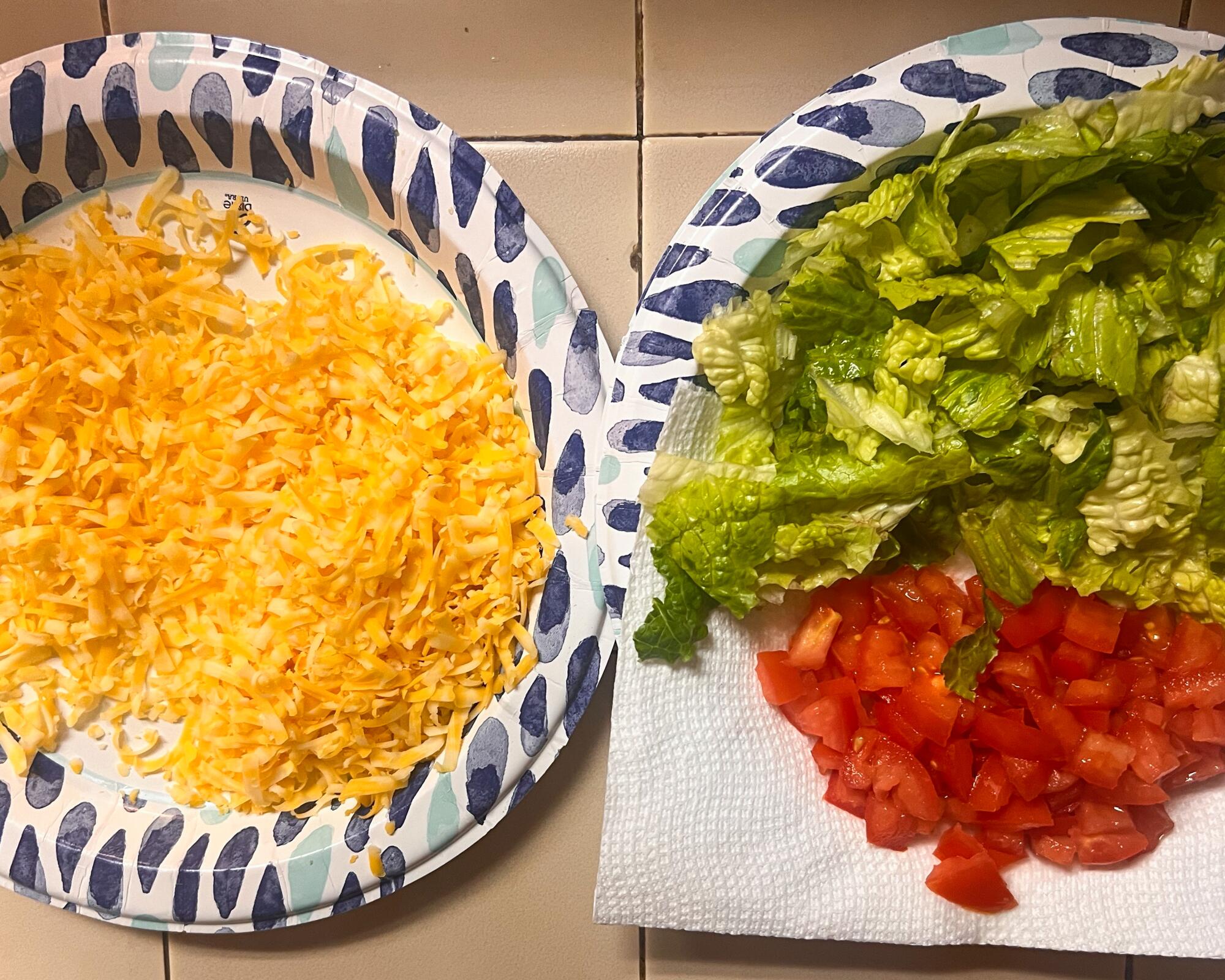

She presents the ingredients like a buffet, with plates of just-shredded medium cheddar cheese, tufts of romaine lettuce, chopped tomato, crescents of avocado and sliced olives spread across kitchen counters. On the stove, cumin- and Lawry’s-scented ground turkey simmers in a covered pan.

Last are the tortillas, which she fries just before assembling the tacos. This is the only time she doesn’t multitask, when I can’t call her into the living room to laugh at some joke on TV and our cross-room conversations lull.

Still, she says she almost always burns the first one.

“Usually the first tortilla is a bit of a test,” she tells me. “That one’s going to tell you if the oil is hot enough.”

Using a pair of tongs, she gingerly lays a corn tortilla in a shallow pool of hissing vegetable oil. Before it can harden into a tostada, she folds it in half, letting each side freckle with tawny-gold spots. Each tortilla takes less than a minute to fry. Then, she sets the still-flexible shell on a plate that’s padded with paper towels to absorb the oil. After the tortillas drain, they hold enough shape to securely cradle the taco fillings but are not so stiff as to break.

Folded corn tortillas just fried in oil drain on paper towels. Black tacos are often served in a fried shell with ground turkey, shredded cheese and lettuce, with sides like Mexican rice and refried beans. (Danielle Dorsey / Los Angeles Times)

Sitting on burners next to the meat are the sides. A cast-iron with tomato-studded Mexican rice and a small pot of refried beans that my mom doctors with hot sauce and shredded cheese. Sometimes one of my brothers or I will make guacamole that she’ll serve with tortilla chips.

In addition to birthdays, my mom estimates that she’s been making these tacos at least monthly since we were kids. Since I moved to Los Angeles in adulthood, the city has introduced me to taquerias and Mexican restaurants with innumerable regional takes on the taco, all reflecting waves of historical and recent immigration to California from Mexico’s distinct regions, and the culinary practices that migrate as well.

But my mom’s tacos stand apart as their own craving, one I never expected to satisfy outside of our home. Then I began exploring L.A.’s Black-owned restaurants as a food journalist, and I kept finding tacos on the menu.

There’s Taco Tuesday at Stevie’s Creole Cafe on Pico Boulevard, the only day you can get hot honey catfish, garlic shrimp and chicken gizzards in lightly fried tortillas with a shower of lettuce and tomato on top. In Inglewood, Ms. Ruby’s Bakery is a hole-in-the-wall that specializes in red velvet cake but lists a taco combo on its menu next to home-style burgers and lemon pepper wings. There’s a legacy of taco-focused spots too, like Taco Pete’s, which opened its first location in Compton in 1989 and now has a second restaurant on West Slauson.

The world often pictures Americans as being white, but the gringo taco was made in Black homes.

— Chef Keith Corbin

I found something familiar in these tacos. Often, the same ground turkey my mom used at home appeared alongside proteins like sauteed shrimp, grilled chicken and steak. There was overlap in the dressings too — strips of lettuce, chopped tomato and strands of yellow cheese, wrapped in a corn tortilla that’s folded and fried. The puffy envelopes loosely resemble the hard-shell tacos found at fast-casual restaurants across the country, an item sometimes labeled the “gringo taco,” and usually disparaged as such by people with ethnic Mexican heritage.

From food trucks to soul food restaurants, here’s how Black chefs are putting their spin on tacos in Los Angeles.

Keith Corbin, co-owner and executive chef of Alta Adams, grew up eating a similar take on tacos to mine.

In his memoir “California Soul,” the Watts native credits his Granny Louella for instilling an early appreciation for food. She was the “big momma” of the neighborhood, a matriarchal figure who took it upon herself to feed and look after siblings, cousins and friends. He describes her as a hustler, selling peach cobbler and burritos made of beef, beans and cheese to make ends meet.

“Tacos definitely played a part in that,” Corbin says. “It was something fast and easy that we were used to. Granny would do the fried shells with the beef, the lettuce, tomatoes, the onions. It blew my mind when I saw that style of taco labeled as the ‘gringo taco.’”

Corbin recognizes that the term refers to an Americanized style of taco. “The world often pictures Americans as being white, but the gringo taco was made in Black homes,” he says.

In fact, the first iterations of what we commonly call the gringo taco were made by Mexican hands. Decades before Glen Bell founded Taco Bell, he was a frequent customer at Mitla Cafe, one of the longest continually running Mexican restaurants in the country, founded by Lucia Rodriguez and her husband, Vicente Montaño, on the west side of San Bernardino in 1937. After Vicente died, Rodriguez married her second husband, Salvador, who helped her expand the restaurant.

Bell, who had a hot dog and hamburger stand across the street, noticed that diners kept lining up outside of Mitla Cafe, which sold tacos dorados for 10 cents apiece. The budding entrepreneur befriended the family and staff, picking up tips and recipes along the way. After opening a couple of small taco-focused chains in the Inland Empire and Long Beach, Bell opened the first Taco Bell in Downey in 1962.

Mitla Cafe is still open in its original location. Now in its fourth generation of family ownership, the menu spans tamales, burgers and enchilada plates, plus a taco they call the “original classic,” with a fried shell, ground beef, diced tomato and shredded lettuce and cheese. It looks and tastes a bit like the tacos of my childhood.

Black tacos also favor the pocho taco that chef Wes Avila introduced at his former taco cart-turned-Arts District restaurant Guerrilla Tacos. (Pocho is a formerly derogatory term for an “Americanized” Mexican American.) He’s called his pocho taco a tribute to the hard-shell tacos his mom made for him as a kid and “very authentically Angeleno.” Like the Black taco, the pocho taco challenges the notion that adapting our cuisines to new regions and environments makes them any less “real” or essential.

Since the beginning, Black tacos have drawn inspiration from Mexican neighbors, like the tortilla makers Burrell would buy from on the weekends, and places like Mitla Cafe. By the time Corbin and I came along, Mexican culture and food practices, in many ways, felt innate to the tapestry of our upbringing as young Black Californians.

My mom learned how to make tacos as a preteen in the early ’70s from an Italian neighbor she would babysit for, Debbie. The youngest of four, my mom lived in the then-burgeoning neighborhood of La Sierra, when homes were just starting to be developed and the elementary and high school had yet to be built.

It was a predominantly white area with just a handful of Black and Latino families, but it served as the first home that my grandparents and many of their neighbors owned. Though some residents kept to themselves, their relatively similar economic status as newly minted middle class helped bridge cultural divides. “In general we weren’t allowed to eat at other people’s houses,” my mother says. “But because [Debbie] lived right next door to us, my parents had to lift that little requirement.”

Debbie was a young single mother with two toddlers and worked in a restaurant bar. My mom was at her house often, even when Debbie wasn’t working late hours, helping her cook or entertain the children.

My grandmother Dorothy, who migrated to San Diego and then Riverside from Jackson, Miss., in the 1950s, used premade taco shells from a box. At Debbie’s house, my mother says, “That was the first time I tried tortillas fried in oil. To me, they were better.”

Though Debbie used ground beef in her tacos, my mom came to prefer ground turkey, a more common meat in her household.

Arguably, ground turkey is the filling that distinguishes Black tacos from the gringo taco. It’s unclear how this became the favored meat in Black households, but when I was growing up in the ’90s, it accounted for 34% of meat consumption in the U.S., up from 19% in 1970. Our family didn’t avoid beef entirely, but it was largely reserved for dining out and family barbecues when my uncles would throw steaks and burgers on the grill.

Growing up, I often felt stifled by Riverside.

My grandparents lived two blocks away. My mother worked for the school district. I would’ve given anything to turn weekend visits with my dad in San Diego, where the boundless ocean seemed a promise of more freedom, into a permanent situation.

I had long vowed to move to Los Angeles as an adult, and after a couple of semesters at Riverside Community College, I did just that. It would be years before I’d soften my view toward my hometown, before I began to recognize the network of support that had nourished my independence.

Perhaps that’s how I came to treat my mom’s tacos as a buoy, a steadying force in the sea of change I’d thrown myself into. As I swapped roommates and apartments, loved and lost and loved again, her tacos went blessedly unchanged. What’s more, I was able to find that comfort nearby, helping to solidify L.A. as home.

In 2013, when chef Alisa Reynolds was preparing to open her California soul restaurant My 2 Cents, not far from Sky’s Gourmet Tacos on Pico Boulevard, she knew she had to have a taco on the menu.

“Being Black and growing up in Los Angeles, they were in every household. Everyone’s mom made tacos,” Reynolds says.

Not wanting to compete with existing Black taco stands that specialized in ground turkey and beef tacos, she considered using frog legs as a filling. Eventually she decided on a taco with six-hour-braised oxtail, roasted tomatoes, strips of kale and a whiskey reduction sauce on a street-size corn tortilla. The plate comes with three tacos, but I’m confident I could eat at least twice that; the sumptuous and tender tacos are some of the best you’ll find in the city, by any hands.

The exterior of My Two Cents, chef Alisa Reynolds’ reimagined soul food restaurant in Los Angeles (Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

Oxtail tacos with roasted tomato, shreded kale and whiskey reduction from chef Alisa Reynolds, the owner of My Two Cents. (Silvia Razgova / For The Times)

“That was my opinion on a great taco that reflected Black culture, but also L.A. and Southern California,” Reynolds says.

During the pandemic, Reynolds launched Tacos Negros, an affordable, takeout-only taco menu that fused Latin and African diasporic flavors.

“We had tacos with arroz con pollo, bacalhau, mofongo. … No one had really done that in that way at that time,” Reynolds says. Tacos Negros became so popular that after restaurants reopened for dine-in, she added the most-ordered tacos to the permanent menu.

“The ground turkey and cheese taco was one that made the cut,” she says. “It was inspired by the typical Black household taco and I wanted it to be familiar but taken to another level.” For Reynolds that meant adding five types of cheeses along with parsley-specked pico de gallo.

“It’s a little crispy but soft-centered, and it’s just very comforting,” she says.

In addition to oxtail and turkey, Reynolds offers fried catfish with house remoulade, agave-jerk shrimp, fried green tomato and plantain and callaloo tacos. Soon, she plans to launch an online-only Tacos Negros shop that will introduce her tacos to the Westside.

After being featured in the HBO series “Insecure,” South L.A.’s Worldwide Tacos gained national attention, bringing into the mainstream a Black take on tacos.

Even as L.A.’s taco culture grows more diverse and expansive, with Armenian Mexican options and entire outposts dedicated to tacos filled with unexpected ingredients, a new league of Black chefs continues to be inspired by the Mexican dishes they had at home.

“I grew up around a lot of Hispanic people in Watts, but really, my tacos are inspired by my mom,” says Keith Garrett, who’s behind the All Flavor No Grease food truck that parks on the corner of Manchester and Western Avenue. “If she says she’s making tacos, it doesn’t matter where I am — I’m on the way,” he says, laughing.

In Leimert Park, Worldwide Tacos gained national exposure after it was featured in actor and producer Issa Rae’s HBO series “Insecure.” The elusive taco window on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard has limited hours and is not available on any delivery or takeout apps, but Black locals know that its tacos are worth the up to three-hour wait. Worldwide Tacos is distinguished by filling combinations you won’t find anywhere else, like piña colada shrimp, red chili lamb, teriyaki salmon and orange duck.

When I’m overwhelmed by the options, I go for the classic ground beef tacos in a crispy seasoned shell with shredded cheese, lettuce and house taco sauce that brings heat to every bite. Worldwide Tacos is a popular stop for Black tourists in L.A., similar to the Dunes apartment building in Inglewood that also loomed large on “Insecure.”

If there’s anything that unites the new and older generations of L.A.’s Black taco makers, it’s the desire to keep innovating. It’s a quality that’s intrinsic to soul food, a cuisine that in part grew out of improvising with scraps and discarded animal parts. Its evolution can be traced from the Deep South to Thomas Jefferson’s White House to the Midwest and coastal cities that people of the Great Migration settled in throughout the 20th century and beyond.

As Black chefs bring their perspective to California soul cuisine, that means not just pulling from our perennial produce but embedding dishes such as Black tacos that defined our experiences growing up in this region.

The evolution is far from over.

At Alta Adams, Corbin and his team recently introduced a plant-based taco that captures the African, Caribbean and Latin flavors that sous chef Binta Diallo grew up with in New York City. Listed as a starter, it features handmade corn tortillas that are cooked on the plancha, stuffed with jerk-spiced sweet plantain and topped with a chunky mango-habanero sauce. With each bite, the flavors ping-pong between spicy, sweet and piquant.

It’s just one hint of what the future holds for Black tacos, and it fits snugly into Corbin’s broad definition of soul food. “It’s food that’s born out of love with the intent to nourish, sustain and feed the soul,” Corbin says.

Just like Mom makes it.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.