Newsletter: The future of rooftop solar is up for grabs in California

- Share via

This is the Nov. 4, 2021, edition of Boiling Point, a weekly newsletter about climate change and the environment in California and the American West. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

For most of this year, people have been asking me: When are you going to write about rooftop solar? Specifically, when are you going to write about monopoly utilities trying to slash California’s wildly successful solar incentive program?

Well, I can finally answer: Here’s my story. It published this week and, for the time being, is available exclusively to L.A. Times subscribers. I hope you’ll consider buying a digital subscription to read the piece and support our journalism, if you haven’t already. It costs less than $100 per year and gives you access to all of our climate and environment reporting.

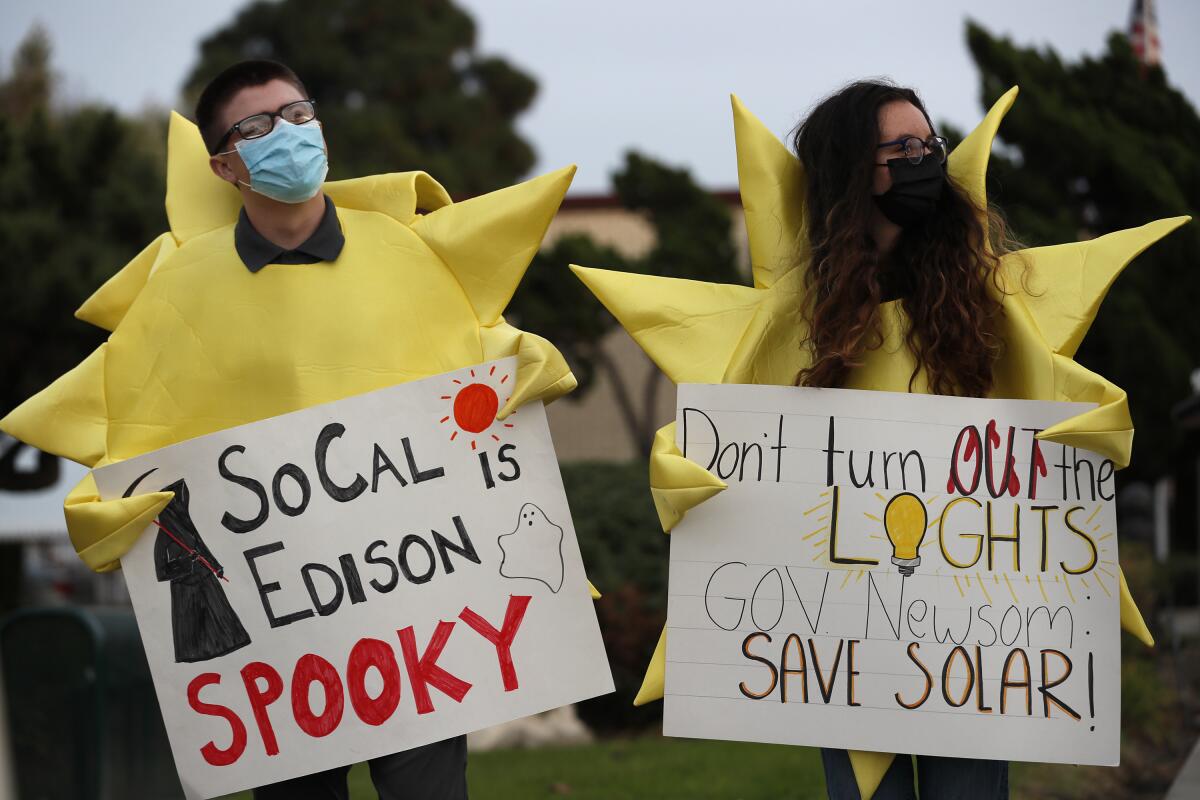

As far as rooftop solar advocates are concerned, the story is simple: Pacific Gas & Electric, Southern California Edison and San Diego Gas & Electric want to quash a technology that threatens their business model. That’s why they’ve asked Gov. Gavin Newsom’s appointees on the California Public Utilities Commission to reduce the electric bill credits homes receive when they sign up for net metering, the incentive program that has fueled the installation of more than 1.3 million solar systems.

That’s not quite the whole story, though.

Yes, the utility industry has been trying to undermine rooftop solar for years, in California and across the country. But at least this time, utilities aren’t the only ones calling for net metering to be overhauled. They’ve been joined by ratepayer watchdog groups that usually find themselves fighting the investor-owned monopolies, specifically the Utility Reform Network and the state Public Advocates Office. The Natural Resources Defense Council also says the solar incentive program needs significant changes.

They argue net metering mostly benefits higher-income homes that can afford solar panels, with the costs falling most heavily on low-income families, many of them people of color. Leading environmental justice groups haven’t endorsed that “cost shift” claim, but several have written that the solar program “disproportionately benefits wealthier, white, single-family homeowners.”

Rooftop solar installers and a diverse coalition of grassroots environmental activists insist those arguments are wrong.

It’s a challenging debate to mediate. Everyone I spoke with had data and research and anecdotes to back up their arguments. Most of them accused their opponents of being biased by industry money, either from the utilities or from solar firms.

Some of those accusations may have merit; read my story and let me know what you think. I’ll note, though, that the utilities have a lot more cash to throw around than their critics. Edison, PG&E and SDG&E parent company Sempra Energy collectively spent almost $2.8 million lobbying state government over the first half of this year, including on a bill that would have undercut net metering, disclosure forms show. By comparison, two solar trade groups and leading installer Sunrun spent about $700,000.

The utility giants say they didn’t take a position for or against the legislation to undercut net metering, Assembly Bill 1139. But organized labor groups representing utility employees certainly did, sponsoring the bill and going to bat for its passage.

And that’s another piece of this not-so-simple story: the role of organized labor in shaping California’s climate ambitions.

Fossil fuel workers, for instance, have fought to protect oil refineries and gas plants from new regulations. And electrical workers have fought to promote large solar farms, which typically create union construction jobs, at the expense of rooftop solar systems. Rooftop solar jobs typically aren’t unionized, a sore point not only for organized labor but for many progressive activists.

It’s hard to find good estimates of the difference between union and non-union wages in the solar industry, although it’s well known that union workers make more. Nationally, solar installers earned an average of $46,000 last year, according to the National Solar Jobs Census, while solar electricians — who are more likely to be employed on union jobs — earned closer to $72,000.

I talked with state Assemblymember Wendy Carrillo, a Los Angeles Democrat and author of the union-backed net metering bill. She told me she’s been “disturbed by some of the comments I have seen in terms of Big Labor getting in the way of climate.”

“Another pillar of the Green New Deal is good union jobs, dignity in the workplace, prevailing wage,” Carrillo said.

At the same time, I heard positive stories about working in rooftop solar from employees of nonprofit installer GRID Alternatives.

As he took a break from installing solar panels at a low-income home in Watts, a predominantly Latino and Black neighborhood in South L.A., supervisor Lee Kwok told me how GRID helped him change careers, offering him nine months of volunteer experience and then a job. His colleague Darean Nguyen got emotional explaining how the Oakland-based nonprofit helped stabilize his life after two decades in and out of prison, training him with skills he’s now using to support his family and help others like him.

“I’m working around people I love, for an organization that has a good mission and good values,” Nguyen said.

Like I said, it’s a challenging debate to mediate. And it only gets more complicated when race enters the equation.

Again, read my story for a full breakdown of the arguments surrounding racial justice. But here’s one data point to ponder: New research out of UC Berkeley finds that in areas served by Edison and PG&E, huge portions of the electric grid can’t accommodate new solar installations without costly upgrades — especially in disadvantaged and predominantly Black neighborhoods.

That doesn’t mean people living in those areas can’t go solar. But it does mean they might have to wait longer to connect their panels to the grid and could lose out on immediate savings, said Anna Brockway, a PhD student and the study’s lead author.

Brockway told me policymakers should do more to support “community solar” installations that serve entire neighborhoods. They’re a sort of middle ground between rooftop solar systems and large facilities in the desert, and supporters say they can benefit low-income communities of color by reducing electric bills and limiting pollution from gas-fired power plants.

“Maybe we should just think of a way to deploy solar that is not specific to the roof of your house,” Brockway said.

Brockway isn’t the only one who thinks so.

The Biden administration set a goal last month of 5 million homes powered by community solar by 2025, a 700% increase from today. Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm called community solar “one of the most powerful tools we have to provide affordable solar energy to all American households, regardless of whether they own a home or have a roof suitable for solar panels.”

Five California lawmakers, meanwhile, recently urged the Public Utilities Commission to adopt a proposal from the Coalition for Community Solar Access, which they said would help low-income homes participate in the clean energy transition. California thus far doesn’t have much community solar, lagging far behind leading states such as Minnesota, Florida and Massachusetts.

So there’s a lot more to the rooftop solar story than net metering.

Still, solar advocates see the Newsom administration’s upcoming decision on the program’s future as an existential threat. They worry a decision to gut net metering would reverberate across the country, since many states follow California’s lead on climate.

In the meantime, some public power agencies — which are governed by their own elected board members — have already slashed solar incentives. That includes the Sacramento Municipal Utility District, or SMUD, which recently reduced bill credits for new net metering customers. When the Imperial Irrigation District ended net metering entirely in 2016, solar installations crashed.

The program’s critics aren’t so concerned. They say rooftop solar will continue to grow, in part because of California’s first-in-the-nation requirement for solar panels on new homes. In their view, this debate is about making sure solar grows sustainably.

Either way, the United States is going to need huge amounts of solar, and fast, to stem the climate crisis. And there’s no shortage of sunlight. The Biden administration recently estimated that solar panels could produce 40% of America’s electricity by 2035. The majority would likely come from large solar farms, but huge amounts of rooftop solar would also be needed.

A National Renewable Energy Laboratory study examining how Los Angeles could reach 100% clean power offered a similar outlook. Researchers assumed that as many as 38% of single-family homes would go solar by 2045, and many apartment buildings too. The city would also need an unprecedented number of large solar and wind farms, but rooftop solar would play a key role.

One last time: Subscribe to The Times and read my story. Here’s what else is happening around the West:

TOP STORIES

Heat waves are especially deadly in neighborhoods with few trees, little green space and poorly insulated buildings that don’t have AC — often due to a history of racist redlining. For a powerful look at how that climate injustice plays out in Los Angeles, see this story by my colleagues Tony Barboza and Ruben Vives. It’s the latest entry in our investigation into extreme heat’s deadly toll. Also check out photographer Genaro Molina’s writeup on what it was like finding images that tell the story.

A California town refused to help its neighbors with water. So the state stepped in. The Times’ Diana Marcum penned this polite but damning story about a largely white San Joaquin Valley city that for years refused to help its much poorer, largely Latino neighboring town solve a drinking water crisis — another example of the environmental injustice that runs rampant in our society.

Half a million undocumented farmworkers are “bearing the brunt of California’s climate crisis — risking their lives and health to harvest in the smoke and sometimes facing financial ruin.” So writes columnist Jean Guerrero, who spent some time with the people who put food on our plates and often have no choice but to keep working when wildfire smoke makes the air hazardous to breathe. And as a reminder that attempts to confront climate change can create environmental injustices too, Ralph Vartabedian wrote for The Times about the already-marginalized communities getting torn apart by bullet train construction.

FIRE AND DROUGHT

Global warming is responsible for as much as 88% of the atmospheric conditions driving worsening wildfires in the West. That’s according to researchers at UCLA and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, who told my colleague Alex Wigglesworth that these changes are happening a lot faster than expected. Not great, Bob. Fires need ignitions, of course, and California’s investor-owned utility companies — the ones I was writing about above — provide them far too often. Hayley Smith reports that the U.S. attorney’s office is investigating PG&E’s possible role in starting the Dixie fire, the second-largest blaze in state history.

For three generations, the McGee family has farmed Christmas trees in El Dorado County. Now drought and fire — and Lou Gehrig’s disease — have made them wonder how much longer they can keep going, The Times’ Robin Estrin reports. In another heart-wrenching tale, sports columnist Bill Plaschke shares an excerpt from his new book — “Paradise Found: A High School Football Team’s Rise From the Ashes” — about a father and son fleeing the flames of the Camp fire, certain they wouldn’t survive.

There’s so much sand built up in the Colorado River that federal officials would normally release a bunch of water from Glen Canyon Dam, to push the sand downstream and replenish beaches at the Grand Canyon. But they say Lake Powell is too low to allow it, prompting conservationists to cry foul, Brandon Loomis reports for the Arizona Republic. Part of their argument is that Glen Canyon Dam wouldn’t be able to produce as much hydropower. That’s a concern across the West as reservoirs dry up, with rural towns that depend on cheap hydropower likely to face electricity rate increases, per the Salt Lake Tribune’s Brian Maffly.

POLITICAL CLIMATE

Congressional Democrats have subpoenaed Big Oil following the first-ever federal hearing on the industry’s history of funding climate denial and disinformation. The hearing didn’t produce any dramatic moments akin to the 1994 congressional grilling in which Big Tobacco executives swore that cigarettes weren’t addictive, but it did prompt Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney to announce that she would subpoena Exxon Mobil, BP, Chevron and Shell for internal documents the companies refused to turn over, as my colleagues Anna M. Phillips and Erin B. Logan report. Meanwhile, in California, executives from the oil company at the heart of last month’s massive spill were invited to testify before state lawmakers but declined, The Times’ Phil Willon reports.

The Biden administration’s methane rule is here. It’s the first time the federal government is attempting to regulate powerful planet-warming emissions from existing oil and gas wells, although implementation would be left to the states, Anna M. Phillips reports. The rule is especially important because it’s still not clear which climate measures might make it through Congress; the latest framework released by President Biden and Democratic leaders includes $555 billion in climate investments, but Sens. Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema haven’t signed off. In another potential blow to climate action, The Times’ David G. Savage reports that the Supreme Court has agreed to hear a case challenging the federal government’s authority to regulate heat-trapping gases.

The Biden administration will conduct the first national assessment of carbon emissions from oil and gas lease sales on public lands. Details here from the AP’s Matthew Brown. But despite Biden’s campaign pledge to end federal fossil fuel leasing, sales are continuing — even as officials now acknowledge that the program could cause billions of dollars in climate impacts.

AROUND THE WEST

A poet is camping just outside the construction site of the Yellow Pine solar farm in Nevada’s Pahrump Valley, protesting the 3,000-acre installation being built on public lands by NextEra Energy. Here’s the story from Meg Bernhard for The Times. It’s a reminder that even climate-friendly energy projects can carry environmental costs, and more broadly that maintaining healthy landscapes and ecosystems is an important piece of the climate puzzle. I also enjoyed this story by Benjamin Ryan for the New York Times about Montana ranchers who are partnering with conservationists to preserve grasslands, a key carbon sink.

Native American tribes lost 99% of their lands to colonization — and the lands they have now are hotter with less rainfall, and in many cases hundreds of miles from their historic territory. That’s according to new research illuminating the scale of yet another climate injustice, Christopher Flavelle reports for the New York Times. Again, paying attention to the land is crucial, as is listening to Indigenous voices. The Arizona Republic’s Debra Utacia Krol writes about tribal activists working to make themselves heard at the climate summit in Glasgow, including their concern that the “30 by 30” plan touted by conservationists — to protect 30% of the world’s lands and waters by 2030 — could turn into another theft of Indigenous land. And in Utah, High Country News’ Jessica Douglas writes about the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe’s fight to shut down a uranium mill they say is poisoning groundwater.

“So many headlines about climate center on the more of it all. More blistering heat. More invasive mosquitos. More devastating floods. But I have become preoccupied by the apparent absence of the mourning dove.” Read this beautifully written story by my colleague Daniel Miller, about the decline in mourning dove populations and their distinctive, wistful call.

THE CLIMATE SUMMIT

Speaking at COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson compared the climate situation to James Bond feverishly working to disarm a bomb while the clock counts down to oblivion. But despite those urgent words, it’s not clear how much action the summit will produce. President Biden criticized China and Russia, two of the world’s largest polluters, for not making any major new commitments, with the strained U.S.-China relationship in particular becoming a stumbling block to climate cooperation, my colleagues Chris Megerian and Alice Su report. Australia’s climate policies are so weak that a Volkswagen executive called the country “an automotive dumping ground for auto engines that our competitors cannot sell in other markets,” Maria Petrakis reports for The Times. And while Biden had hoped to demonstrate America’s commitment with a newly signed climate bill that he could tout to world leaders, domestic politics have thus far continued to stymie his Build Back Better agenda.

There have been some breakthroughs at COP26, though, including global pledges to limit methane emissions and end deforestation. Details here from Anna M. Phillips and Chris Megerian, who note that there’s a big difference between countries promising to do those things and actually doing them. Ending deforestation will be especially tricky, although there’s some reason for optimism; see, for instance, this story by The Times’ Kate Linthicum and David Pierson, with photos by Luis Sinco, about a small-town success story in the Amazon rainforest, where ecotourism has replaced logging as a source of income for some locals.

Big picture, the fate of the world rests with the small handful of countries responsible for the vast majority of carbon pollution. Our daily podcast, The Times, hosted a robust analysis of those countries, including China, the U.S., India, Russia and Japan. They control the fate of small Pacific island nations being inundated by rising seas — nations whose leaders have trouble even getting meetings with President Biden and other powerful figures, Anna M. Phillips reports. Interestingly, Anna also notes that some environmental groups had called for the climate summit to be postponed, arguing the continued scarcity of COVID-19 vaccines in much of the world would make it hard for leaders of developing nations to attend. And speaking of summit attendance, Gov. Gavin Newsom backed out at the last minute, citing unspecified “family obligations,” Phil Willon and Taryn Luna report.

ONE MORE THING

When I saw the headline of Times columnist Patt Morrison’s latest piece — “Who killed L.A.’s streetcars? We all did” — I thought to myself, “I hope she references one of my favorite Disney movies, ‘Who Framed Roger Rabbit.’” Patt never disappoints, and this piece was no exception. She evaluates the real-life conspiracy theory that inspired the half-animated, half-live-action movie — that a cabal controlled by Big Oil brought down the city’s iconic Red Cars — and concludes there is, indeed, at least some truth to it.

Yes, Disney made a movie about an oil industry conspiracy to kill transit in Los Angeles. You can’t make this stuff up.

We’ll be back in your inbox next week. If you enjoyed this newsletter, please consider forwarding it to your friends and colleagues.