Who killed L.A.’s streetcars? We all did

- Share via

Suppose you’re thinking of moving to Los Angeles, and you ask your friends, what movies should I watch to learn all about the place?

Easy, they say. “Chinatown,” “Once Upon a Time... in Hollywood,” and “Who Framed Roger Rabbit.”

That’s fine — if you’re willing to let movies teach you history. But do remember, please, that “Chinatown” is a brilliant but truth-adjacent film and that “Once Upon a Time” delivers a happy grisly alternate ending to the Charles Manson saga.

And as for “Roger Rabbit,” do you really want your source material about L.A.’s electric streetcar system to come from a cast of animated lagomorphs? Next to the Black Dahlia, that is probably L.A.’s favorite murder-conspiracy whodunit: Who killed the Red Cars, once the grandest electric streetcar system in the nation?

Just as Brooklynites still curse L.A. for luring away the Dodgers, who have now played in L.A. for about as long as the Dodgers did in Brooklyn, Angelenos of many ages get both misty-eyed and ticked off over the loss of a Red Car system that closed down 60 years ago — which is about as long as it was in operation.

Explaining L.A. With Patt Morrison

Los Angeles is a complex place. In this weekly feature, Patt Morrison is explaining how it works, its history and its culture.

What were the Red Cars?

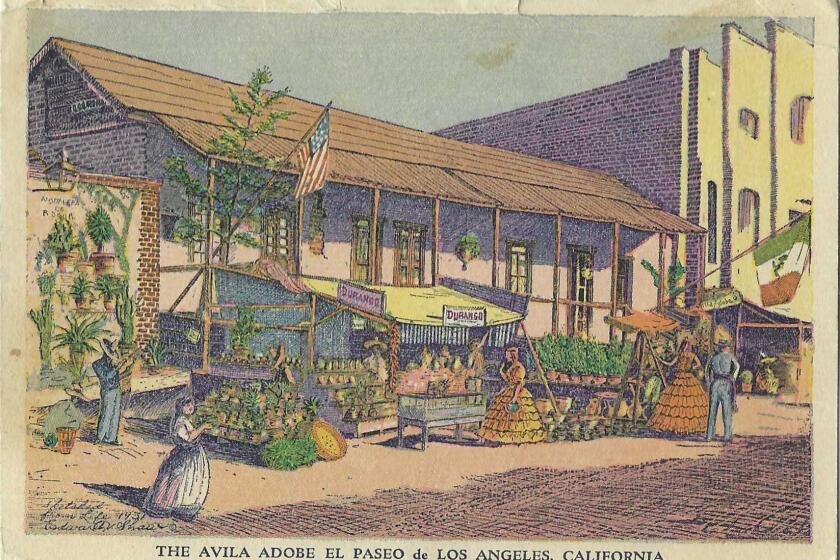

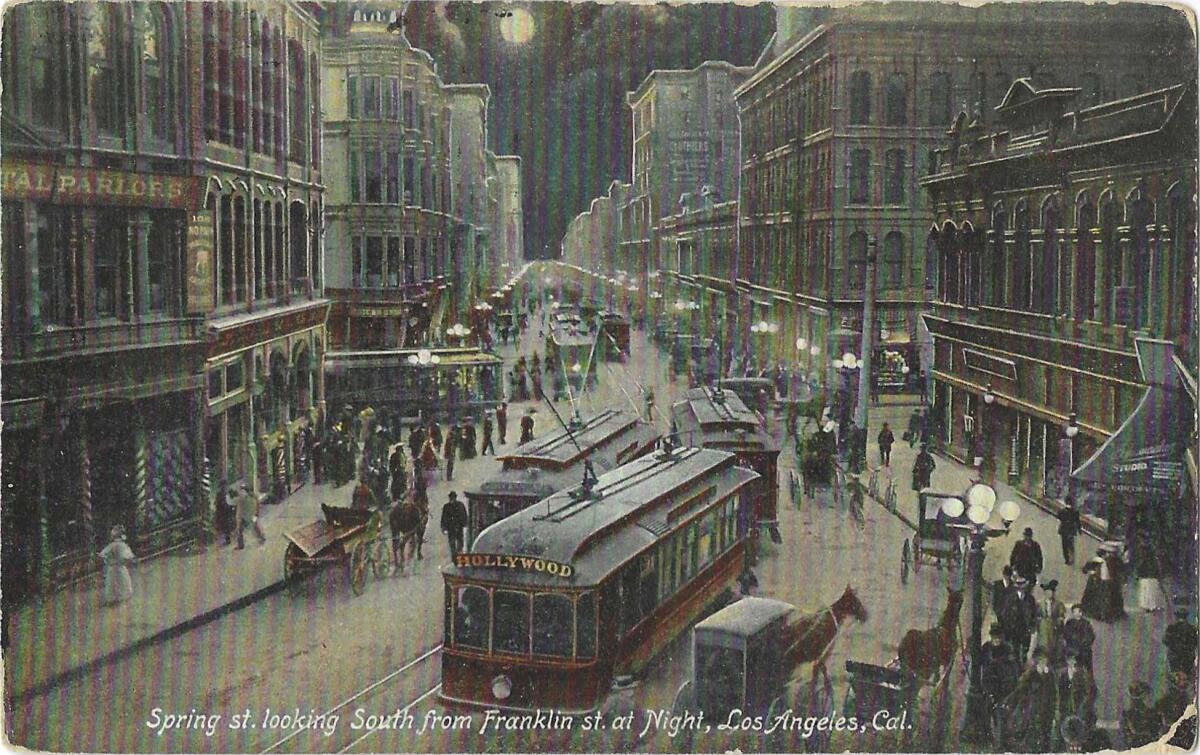

That’s the name we gave to the electric-streetcar system, debuted in 1901, that included inter-city electric streetcars and yellow intra-urban streetcars in central L.A.

A few private transit undertakings had varyingly formed, re-formed, gone bankrupt, been taken over or combined since the late 19th century, using cable cars, horse-drawn cars, funiculars, electric trolleys — all manner of movable systems. What would become the Yellow Car system ran these mixed means of motion throughout the L.A. core and nearby suburbs before the company was sold to Henry Huntington in 1898.

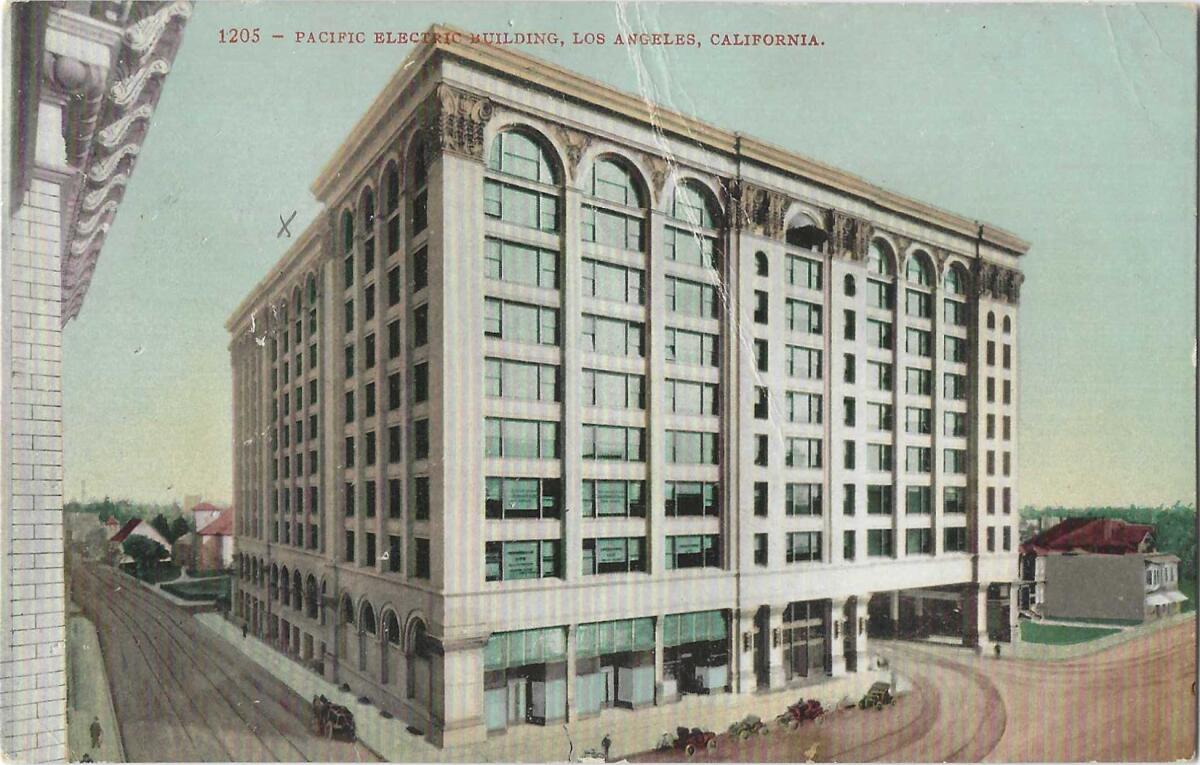

By 1910, the Red Cars reached into four counties: L.A., Riverside, San Bernardino and Orange, on nearly 1,200 miles of track, more than twice what Metrolink operates today. Yet it wasn’t technically a public transit system at all. The public rode it, but the public — meaning any government agency — didn’t own or operate it.

Nor was the system built to move people around cheaply and efficiently. The tycoon Henry Huntington didn’t build it to make money on nickel fares; he built it to sell real estate. He made his money when people took the ride far out of town, bought a piece of Huntington’s land and built a house there, knowing that with the Red Car, you could live in the ‘burbs and still get to work and to shops downtown. It was Huntington’s loss leader, in the way that stores lure you in with a $199 Sony PlayStation 5 knowing you’ll decide the savings justify buying a thousand-dollar flat-screen TV.

Why was it important to L.A.?

Red Cars didn’t just get people from Point A to Point B. They helped to create Point A and Point B. Towns like Burbank and Alhambra grew spectacularly once the Red Car reached them. When the word spread that Huntington was buying land and a small trolley line in Redondo Beach, the land speculation was nuts; one building that sold for $4,000 in the morning resold for $20,000 that night. Other sellers of land wised up and made sure their advertising told prospective buyers how to get there by Red Car; so did merchants and amusements. The system made even the farthest towns and neighborhoods feel connected.

How big was the system?

In its glory years, it ran from the San Fernando Valley to Long Beach and the amusements of Balboa Island in Orange County, from Santa Monica to Riverside and San Bernardino counties. When Charles Lindbergh visited in 1927, Pacific Electric laid on extra cars so people could come from as far off as Riverside to see him.

Who rode it?

In its best years, virtually everyone. It was a small-D democratic ride: businessmen and workingmen, ladies who lunch and the ladies who prepared breakfast, lunch and dinner for others. They rode it to work. They rode it to weekend larks around town, to the beach, the foothills. As a harbinger of things to come, starting around World War I, ads in The Times for restaurants or department stores or amusements included both the name of the Red Car line and the automobile directions to get there. Tourists paid a dollar to take the “balloon route,” a leisurely, circular tour through Southern California beauty spots, which by the sheerest coincidence also had buildable lots for sale.

Was it fabulous?

For a long time, yes. At their best, the Red Cars ran at 40 or 50 miles an hour, powered by overhead wires. They were as long as 50 feet, wood and steel, red with golden letters. Their local counterparts, the Yellow Cars, took you through the central city for a nickel. From 1928 into the Depression, you could buy “a day for a dollar” all-day Sunday pass.

Southern California’s manufacturing helped win World War II. But the war effort and decades of polluting industry have left a toxic legacy.

Who operated it?

The system changed owners more often than a haunted car in a horror movie, and the transactions get just as murky, so bear with us — this is the abbreviated version, insofar as it’s comprehensible: By the time Huntington started the system in 1901, he had also acquired what we know as the Big Yellow Car system, the Los Angeles Railway Company, streetcars operating within central L.A. itself. In 1910, according to Pacific Electric company records in the state’s archive, Huntington sold his shares to Southern Pacific, and the next year, the “Great Merger” combined almost all of the inter-urban railway systems in the four-county areas into what was still called the Red Car system. The Yellow Cars were still operated by the Los Angeles Railway Company.

Here is where it starts to read like the “begats” in the Bible: The Southern Pacific pretty obviously wanted a ready-made train system, not a trolley system. It began prioritizing freight instead of passengers, and passenger service was neglected. As early as 1917, six years after the “Great Merger,” Southern Pacific was abandoning Red Car lines, and in time it sent out buses instead of trolleys to move a dwindling number of passengers (read about competition below). The old Red Car system was sold in the early 1950s to a bus company called Metropolitan Coach Lines, which sent more buses out where electric cars once rolled. And on April 9, 1961, a Sunday, at 3:45 a.m., the last surviving passenger rail line made the run from L.A. to Long Beach, playing its swan song — the characteristic air whistle, two longs, a short and a long. “Replacing the Red Cars will be a fleet of buses,” The Times wrote. Long Beach had gone to court in a Hail Mary bid to stop the line from shutting down and lost.

At 7:42 a.m. on March 3, 1958, The Times wrote, the LA Metropolitan Transit Authority “took the plunge into the transportation business” when it took over Metropolitan Coach Lines and Los Angeles Transit Lines, for just north of $35 million. LAMTA was itself hoovered up in 1964 by the Southern California Rapid Transit District ... which you know as Metro, the L.A. County Metropolitan Transportation Authority. So it is, as the archbishop of Canterbury says sarcastically in Shakespeare’s “Henry V,” “as clear as is the summer sun.”

As for the Big Yellow Car intra-urban system, it was sold at the end of World War II to American City Lines, a subsidiary of a Chicago-based company called National City Lines, which was buying up dozens of local transit systems like L.A.’s all across the country, pulling their plugs and putting buses in their place.

And here, as The Times once wrote, is where conspiracy theorists have a point: Who were National City Lines’ chief investors? You may now hiss: General Motors, Firestone Tire and Rubber Company, Standard Oil of California, and Phillips Petroleum — all of them manufacturers of bus and bus-related products. All companies that stood to profit handsomely when electric streetcars were pushed aside for buses. This did not go unnoticed by the feds. There was a trial. There were convictions. There were fines. But was there a conspiracy? Read on.

What was the Red Cars’ competition?

Angelenos began cheating on the Red Cars with their own flivvers even before World War I. In 1920, Pomona switched from electric trolleys to buses running on fuel, and other cities followed suit; buses didn’t need tracks and could change their routes in an instant, which you can’t do with overhead wires. Yet even in 1924, Pacific Electric was having a peak year — 120 million rides, many of them to downtown’s Roaring ‘20s theaters and businesses. The Depression clobbered that. By 1933, ridership was off by 50%, and the next year, it dropped another 50%. People stopped riding them because they’d gotten shabby; they got shabby because people stopped riding them.

Worst, they had lost their competitive edge. Speeds that had once been 40, even 50 mph dropped into the teens. Where Red and Yellow Cars once had streets pretty much to themselves, now they had to share them with cars and buses all stuck in the same traffic jams. And honestly, if you had to spend an hour mired in traffic, which would you choose — a crowded, too hot/too cold streetcar, or your own personal chariot?

Pacific Electric offered the city a plan for avoiding auto messes: elevated tracks. But in a 1926 election, Angelenos turned down the idea. The Times had crusaded vituperatively against the idea as too degradingly urban East Coast, “alien to the spirit of Los Angeles.”

During World War II, gas rationing perked up streetcar ridership something pretty, but that was soon over. People wanted their cars, and at almost every level of government money marked for “transportation” went almost entirely to highways and freeways and buses. The trolley cars shared the fate of the family horse: abandoned for gas-fueled horsepower.

The Red Cars were stacked up and sold for scrap, offered for as little as $500 each with no takers. Some were shipped to a second life in Argentina. The last Yellow Car followed them into oblivion in 1963.

Native American settlements were first, and then the rancho system -- Spanish then Mexican land grants throughout California -- were built atop and near those settlements and still shape our geography and place names.

Was there a conspiracy?

Yes, and no. The Times wrote in 2003, sorting fact from fanciful, that in 1946, the U.S. Justice Department realized what National City Lines was up to, and filed an antitrust suit for conspiracy to monopolize transit. But before the suit came to trial in Chicago, those big-name businesses propping up National City Lines sold out, and what kind of lawsuit could the feds get against a husk of a corporation?

The verdict in the 1949 trial was a little of this, a little of that. One count charged GM and the tire and gas companies with violating the Sherman antitrust act to get mastery over transit companies and put the competition out of business, for the benefit of the companies controlled by National City Lines. The defendants were acquitted of that. But on the second count, violating the Sherman Act to drive out competition when it came to selling busses and supplies to National City Lines’ transit companies, the jury said “guilty.” And even though GM and the other businesses had abandoned the National City Lines company before the trial, each was fined — a pittance: $5,000 each, with individual company officers having to dig into their pocket change for $1 each. The walloping total: $37,007.

Out of all this came the confession by the villainous Judge Doom in “Who Framed Roger Rabbit,” that in order to convert L.A. into a nirvana of freeways and gas stations and drive-in restaurants, “I bought the Red Car so I could dismantle it.”

If you do indeed regard the machinations as a conspiracy, it could all be like cops framing a guilty man. The victim was already dying, losing money, losing passengers, losing its advantage over the car. Still, as the book “Los Angeles A to Z” put it, “the company’s demise was orchestrated, rather than left to chance.”

For all of the reasons you read above, the Red and Yellow Car systems were staggering already. Like the “Murder on the Orient Express” plot, many hands stuck in the knife: the companies fined by the feds, our elected officials who pushed public money into supporting cars, not public transit — and us.

We did it, with our besotted fondness for our cars. But we love the conspiracy notion because it gets us off the hook, and it helps us rationalize the death of a once-splendid transit system with the idea that only a big, wicked cabal could have savaged such a civic jewel. As Portland State University scholar Martha J. Bianco wrote in her 1998 essay debunking the conspiracy theory, “If we cannot cast GM, the producer and supplier of automobiles, as the ultimate enemy, then we end up with a shocking and nearly unfathomable alternative: What if the enemy is not the supplier, but rather the consumer?”

Even in “Roger Rabbit,” a film selling the Red Car conspiracy notion, how do the characters zip around town to resolve their problems? In automobiles.

L.A. is a place like no other. You’ve got questions. Patt Morrison probably has answers and can definitely find out.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.