- Share via

The fire refugees arrive with regularity at the checkpoint on Pacific Coast Highway. They come alone or in pairs, lining up behind the clutch of police cruisers and a National Guard Humvee, pleading to get back to homes inside the Palisades wildfire perimeter.

They want medicines and other necessities, sure. But they also want a sense of knowing: What has the great Palisades wildfire done to their homes and to their lives?

When Steve LaBella arrives, it’s with an urgent request from his father, Len, who evacuated in such a rush on Jan. 7 that he left behind a treasured keepsake — a Purple Heart that his father, Leonard LaBella Sr., earned in Germany near the end of World War II.

Like virtually everyone else, Steve LaBella is turned away by a police officer. But then he spots a sunburned civilian on the inside of the checkpoint. He calls out to the stranger, who he later learns is Stephen Foster, who quickly agrees to take LaBella’s house keys and look for the missing medal.

Twenty minutes later, Foster returns to PCH with not only the Purple Heart, but several family photos, wrapped carefully in a tablecloth.

“I think he has no idea the gift he gave us in that moment, to know the house had survived and to receive these things,” says LaBella, who soon delivered the Purple Heart to his tearful father. “It was a gift of some level of humanity, and connection and community and even love. And it came from someone who was a complete stranger.”

Foster is that rare exception in this deadly and tragic fire season. He’s a Samaritan scofflaw, soldiering on inside an almost entirely vacated neighborhood next door to the Getty Villa.

Foster and his son, Colton, stayed on through the worst of the wildfires, arguably helping to save as many as 10 homes. They are now supplying food and other necessities to fellow fire holdouts, and serving as couriers for dozens of others living outside the fire zone. In the process, the Fosters have created a small island of civilization in a sooty, fire-blasted wilderness.

Foster, a 52-year-old Century City real estate attorney, has made his home, where he also grew up, habitable by securing a generator that’s now powering the two-story house and those of two neighbors. A new Starlink satellite hookup assures communication with the outside world.

He and Colton, 21, have delivered groceries, medicine and dog food to others who refused to leave the neighborhood — including nonessential essentials like beer and a coveted bottle of Scotch whisky.

While the checkpoint blocks virtually all outsiders from coming into the fire zone, police and sheriff’s deputies have let a few supplies past, knowing that the Fosters are bringing relief to others. The Fosters pick up the necessities at the PCH pinch point. Larger improvements, like the generator, have been driven in, escorted by law enforcement cruisers.

Among the recipients of the family’s generosity: a 75-year-old bachelor, left alone and fending for himself in the Sunset Mesa neighborhood, where there is no electricity and only cold water.

“I call him Saint Stephon, Santo Stefano. Saint Steven,” quipped Michael Gessl,

one day this week. He’s the retiree on the receiving end of a bottle of Scotch, a bag of dog food and multiple other Foster-family donations.

- Share via

“You can just call me a good neighbor,” Foster replied.

A Redondo Beach Fire Department captain — who initially ordered the Fosters out of the neighborhood, several times — also credited them with helping to save a string of homes. Said Capt. Kenny Campos: “Situationally, it was pretty heroic.”

The sobering counterpoint to their success emerged less than 10 minutes away, in a more remote Pacific Palisades neighborhood. Along Glenhaven Drive, a vibrant retired engineer with a fearsome work ethic was found dead.

Mark Shterenberg, 80, had messaged his wife at about 9:30 p.m. on Jan. 7 that their home seemed safe. He last spoke to a neighbor not long before midnight. Four days later, investigators found remains in the rubble of his home, along with Shterenberg’s glasses.

“In my heart,” his granddaughter told The Times, “I feel like he was trying to protect everything that he built for his family here.”

The California Emergency Services Act of 1970 gives police broad authority to arrest residents who disobey evacuation orders. The violation is a misdemeanor, punishable by a fine of up to $1,000 and six months in jail.

Firefighters say they are too busy managing multiple other variables to spend critical minutes trying to uproot homeowners who ignore evacuation orders. Still, fire crews also report their dismay when they have to divert their attention from flames to rescue would-be heroes.

“We probably told Steve two or three times, ‘You gotta evacuate. It’s coming through here soon,’ “ recalled Capt. Campos. “And he just said, ‘Nah, I’m staying.’ I don’t have time to argue in a case like that, so it’s [like] ‘Do what you please.’ “

Firefighters who worked for several days in the neighborhoods adjacent to the Getty Villa also conceded that the Foster’s situation, while clearly threatening, wasn’t dire. Their two-story home had recently been remodeled and was low on flammable materials. The house sits on relatively defensible ground, partly because of a concrete backyard basketball court.

“As a fire captain, I have to say it’s probably best to evacuate,” said Campos. “But it’s also your own prerogative to protect your property.”

Foster’s wife, Erika, and disabled mother, Betty, fled Jan. 7, along with a caretaker, two dogs and a 16-year-old cat, Bailey, who’s said to rule the Foster family roost. Daughter Cassidy, 18, had just departed for Eugene, where she attends the University of Oregon.

Through the night, the two Foster men defended homes up and down Surfview Drive, lugging their own heavy-duty hoses from house to house and wielding shovels and a pickax to move earth and smother flames when the water pressure got low.

With snowboarding goggles fending off the intense heat, they watched as a backyard eucalyptus tree burst into fire. They doused the flames, but had to repeat the process when the tree caught fire two more times.

“It was apocalyptic.” Foster said, still red-eyed a week after the struggle. “We weren’t going to do anything stupid. We were just gonna stay and do what we could, until we knew we couldn’t control it.”

More than once, Erika Foster called. “She was, like, scared to death. She was like, ‘If you guys die in that fire, I’m gonna kill you … again,’ “ Colton, a Santa Monica College student, said with a grin. “Which I love. I love that she cares. And she had very valid reasons to be so worried.”

A friend also called to tell Colton he was crazy not to evacuate. “But I don’t want to leave my dad alone,” Colton later told a reporter. “It wasn’t a one-man job.”

By noon on Jan. 8, during a period of relative calm, Foster approached Campos and his three-man engine company to talk strategy. They shared a chuckle about what they’d endured. Foster offered the exhausted fire crew drinks, snacks and his bathroom. A mutual-admiration society began to bloom.

Afterward, one neighbor texted with half a dozen others: “You didn’t hesitate for a second,” the message reads. “You put everything on the line to protect what we all hold dear. ... I’ll never forget what you did for all of us.”

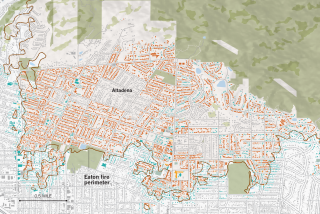

Tales of others saving homes have been emerging from Altadena and other parts of the Palisades and Malibu. What’s continued to set the Fosters apart is their work bucking up evacuees and neighbors. Along with

next-door neighbor Chad Martin, who returned shortly after the fire passed through, they have become surrogates for the refugees.

They regularly make sandwiches and hold cookouts for the handful of remaining neighbors and the occasional first responder. They’ve cleaned debris from streets and yards. When they spotted outsiders patrolling the neighborhood on bikes, with empty backpacks, they alerted police about potential looting.

Learning about the Fosters’ roost, dozens of people have asked them to go to their houses to retrieve necessities.

The children of one elderly couple rode electric bicycles to the police checkpoint on PCH, just below the Getty Villa. They dearly wanted to retrieve their 87-year-old mother’s wheelchair and hearing aids, along with some medication.

Foster soon headed off for the house.

“We couldn’t stop talking about how giving he was in that moment,” said Marie Effertz, who shuttled the recovered items to her parents. “It seemed like he was spending all his time helping people.”

Foster also took a video of the home and gave it to Effertz. She could see a broken window and muddy footprints, the marks left by firefighters struggling to save the family home. “It helps me feel like I have some sort of answers,” she said. “He was a really huge asset for us.”

Hundreds of other families clamoring to return have been told they must wait. Officials say it is not yet safe to return. Crews are still clearing downed power lines, working to restore electricity and continuing the search for those who didn’t survive.

Foster acknowledges he has thought, more than once, about how good it would feel to be outside the perimeter. Maybe for a hot tub soak. Or a massage. And especially to be with Erika, his sweetheart since high school.

But he realizes that, if he exits the fire zone, he will not be allowed back in. The guys from Redondo Beach Fire Department, Engine 62, have stopped by more than once, and Foster treated them to a barbecue dinner.

In the meantime, people seeking help keep arriving at the PCH checkpoint, so Foster remains on duty, with no immediate plan to leave. There’s still so much to do.

Times staff writer Corinne Purtill contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.