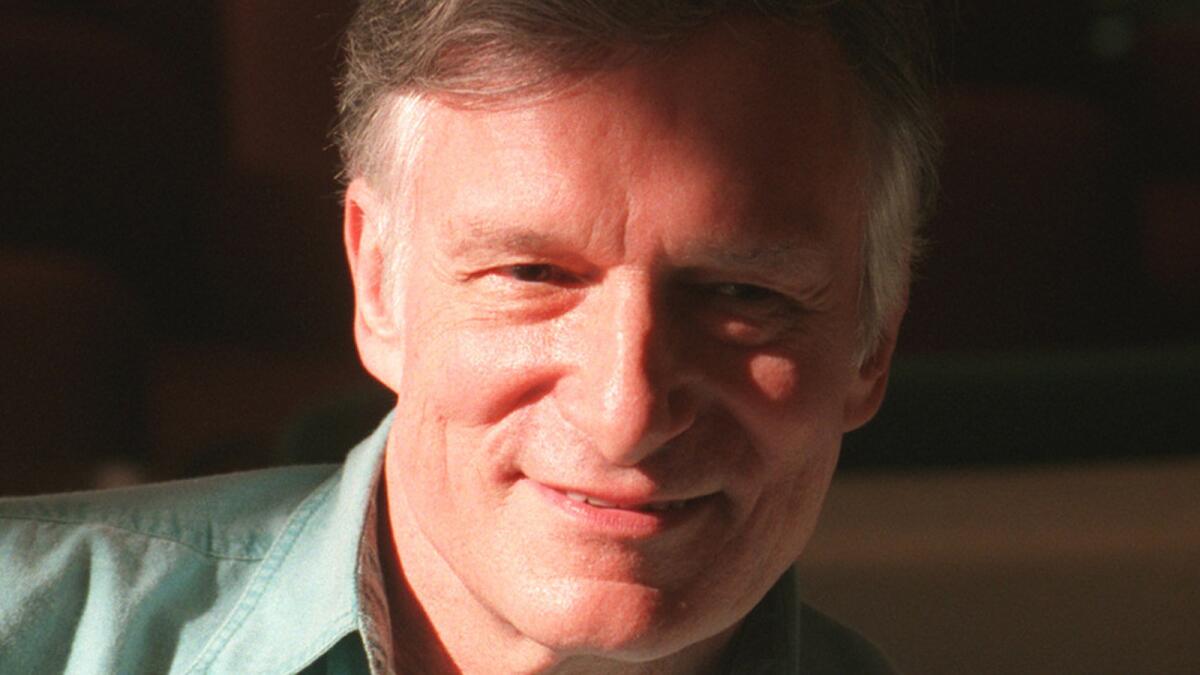

From the Archives: Hugh Hefner: In the shadow of AIDS, examining what’s left of the sexual revolution

- Share via

Playboy founder

The yellow warning sign on the drive reads, "CHILDREN AT PLAY." The sauna--once a site for strictly adult games--is now used to store toys. The only bunnies in evidence at the Playboy mansion are the furry four-legged kind, part of Hugh Hefner's personal zoo.

At 68, Hugh Marston Hefner is five years into his marriage to former Playmate Kimberly Conrad. He has two children with her, and has turned the day-to-day operations of Playboy Enterprises over to Christie Hefner, his daughter from his first marriage. These days he's writing his autobiography, looking back at a life that, by any measure, has been quite an adventure.

Hefner was 27 when he published the first issue of Playboy, in 1953. It was an instant hit. Hefner's genius was in removing the furtive, plain-brown-wrapper feel of the pin-up publications of the day. He designed his magazine to be kept on the coffee table, not hidden under the bed. In the pages of Playboy, he associated sex with money, sophistication and style. And Hefner made himself into the embodiment of that Playboy ideal--a regular guy who digs cool jazz, has a really neat bachelor pad and lots of sex with lots of gorgeous women.

During the 1960s and '70s, his magazine spawned an empire--a broad-based merchandising operation, Playboy clubs and casinos and the Playboy cable TV channel. Hefner was at the helm, often with the help of Dexedrine, and always with a Pepsi. He took the company public and then moved from Chicago to Los Angeles in 1975, purchasing an estate built in the 1920s by Arthur Letts Jr., whose father founded the Broadway department stores. Hefner transformed the Letts home into his Playboy Mansion--complete with redwood forest, aviary, hot-tub grotto and game house. Parties were frequent and wild.

But with the dawn of the 1980s, the foundations of the Playboy empire were shaken. To many young people the magazine was either offensive or a curious anachronism. Circulation plummeted and, in short order, the company lost gambling licenses in London and Atlantic City.

He made a quick and seemingly full recovery. But Hefner says he was forever changed by the experience. The announcement of his marriage made front-page news in 1989, and the once highly visible Hefner now jealously guards his new family's privacy.

Hefner wore his trademark silk pajamas for this interview. His Pepsi is now diet--and caffeine-free. Across an oversized backgammon table he talked of sex, gender and repression.

You've always been right in the middle of the battle of the sexes. How would you characterize the relationship of men and women right now?

I think it's a very mixed message today. I think our society is fragmented. Messages regarding human sexuality have always been mixed in America. We are a schizophrenic nation. We were founded initially by Puritans, who escaped repression only to establish their own. Then the founding fathers gave us the Constitution to separate church and state. But the one thing that got left out of all those laws was human sexuality.

The relationship between the sexes is in many ways suffering from even more confused messages than ever before. You have the religious right and some left-wing feminists both taking very conservative postures on sexuality and the images of sex. There is within the women's movement an antagonism towards sexuality and towards the opposite sex that obviously makes no sense and certainly wasn't what (Betty) Friedan had in mind when she wrote "The Feminine Mystique" and started it all in the early 1960s.

We're fascinated by our sexuality and frightened by it. And during the Reagan and Bush era you got an entire decade of anti-sex government. Sex is not the enemy. It is the beginning of civilization, family and tribe. Sex can be twisted and exploited, but in its most essential form, it's the best part of who we are. And it frightens us.

How did your efforts to open up the dialogue about sex, gender and sexuality either add to the confusion or provide some clarity?

This may be self-serving, but I sometimes feel that Playboy is one of the very few moral compasses when it comes to sex in America. Very early on, Playboy was saying the McMartin (child molestation) case was just another Salem witch hunt. We got sexual hysteria in many forms in the 1980s. It included a wave of McMartin-style allegations that had nothing to do with any real child abuse, and it was fed by AIDS. I said early on that if AIDS did not exist there is a portion of this country that would have had to invent it.

How has the reality of AIDS transformed the philosophy behind Playboy?

I think there was a window of opportunity that lasted for two decades--from the invention of the pill in the early 1960s until the arrival of AIDS at the start of the 1980s. It was almost like the Garden of Eden. It was guilt-free sex with relatively few negative possibilities. Now the game has changed. But remember, disease has always been a consideration, and informed sexuality is always what Playboy has been about.

Playboy began editorializing about AIDS before any other national magazine, and brought some rational thought to the subject when the (television) networks and the rest of the mass media were really involved in a form of hysteria.

There was a cover story in Life magazine in early 1985--the shock headline was, "AIDS--Now We Are All At Risk." Well that's a lie. We are not all at risk. The risks are very clearly defined and related to specific behavior. There were people who said, "When you have sex with somebody, you have sex with anyone they ever had sex with." Again, simply not true.

Have you always been somewhat preoccupied with matters of sex?

I can remember in my adolescence feeling that many of the things that were hurtful and hypocritical in society were things related to sex. They included the kind of censorship laws that existed in the movies and books when I was young.

I remember reading a story in Life magazine in 1939. I was an eighth-grader, 13 years old. It was a story of a young couple, in their teens. She had become pregnant. That just wasn't supposed to happen to nice, middle-class kids. They didn't know what to do, and she suggested they kill themselves. He killed her, but then couldn't bring himself to commit suicide, and was on trial. Both families blamed themselves for the tragedy.

That story, even though I was a kid, had a tremendous impact on me, and I obviously read into it something about my inability to communicate with my own parents about those kinds of things. So I had a concern about repressed sexuality long before I came up with something called Playboy. I realized early on that, in a free society, if you are not free in your own bedroom, then you are not free at all.

You supported Bill Clinton during the presidential race. How's he doing?

Mixed. The good news is that he's coming from the right place. We had a federal government that was in favor of censorship, wanted to make abortions illegal, and was against sex education and birth control--both in the United States and abroad. We had an attorney general, Edwin Meese, who had no concept of law or the Bill of Rights. Clearly in these areas, Clinton represents a great improvement. And he's really trying to do something about the deficit, and reforming welfare, about health reform. It's just his execution that seems to be a problem.

You've made the comment that there are countries all over the globe where the situation in terms of sexuality and gender is much like it was here in the U.S. during the 1950s. Is Playboy's growth going to come from the global market?

Yes, because with the end of communism and the opening of Third World markets, the potential for Playboy is huge. It has been said that the two most famous trademarks in the world are Coca-Cola and the Playboy bunny rabbit. There is certainly no one else in our area that represents the American dream in this particular kind of way. That rabbit means economic freedom, personal freedom and political freedom. That potential is unlimited.

Your stroke in 1985 — what is it like to realize that you are no longer working like you used to?

It was pretty dramatic. It happened about two in the morning. I was reading from a newspaper to a girlfriend and, all of a sudden, I couldn't read the headline. I lost the ability to find the words for simple objects. The doctors showed me a tie, a belt--I knew what they were but I couldn't find their names.

But I was lucky. I had a good doctor, and the recovery was quite rapid. My feeling at the time was that I had just been missed by a train or a bus. I'd been knocked off the road, but I was going to recover. And so it generated a tremendous feeling of optimism, and a sense of relief. I was born again--in the best sense of the word.

After my stroke I put down much of the luggage of my life. I didn't have to prove anything anymore--in business, in my personal life or whatever. And now, as I work on my autobiography, I enjoy looking back, seeing the connections, the causes and effects of my life.

Plenty of people have predicted your demise--both personally and that of the magazine. And yet you've survived. How did you do it?

I've always had a tremendously optimistic attitude about life, and the setbacks are never really setbacks for me, because I see it as a part of the adventure. And if you don't hold onto your dreams, you're a very foolish fellow, because dreams are what life is about.

But from the beginning there was a need for some in this society to believe that Playboy and the things I stood for were fundamentally flawed, and that I would somehow have to pay for my sins. But I understand that--it comes from the Puritan part of who we are. I, myself, am a direct, 11th-generation descendant of William Bradford, one of the first, staunchest Puritans who came over on

One of the reasons that I have such tremendous satisfaction at this point in my life is because I know I've made a difference. I've made a difference in a way that really matters to me. I see a lot of terrible things going on in the world, but there are some good things going on too, and I feel I've been a part of that. I really do feel I have been on the side of the angels.*

Steve Proffitt is a producer for Fox News and a contributor to National Public Radio's "All Things Considered" and "Morning Edition." He interviewed Hugh Hefner at the Playboy mansion, in the Holmby Hills neighborhood of Los Angeles

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >> »

ALSO:

From the Archives: Hugh Hefner's life pushing boundaries started with comics

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.