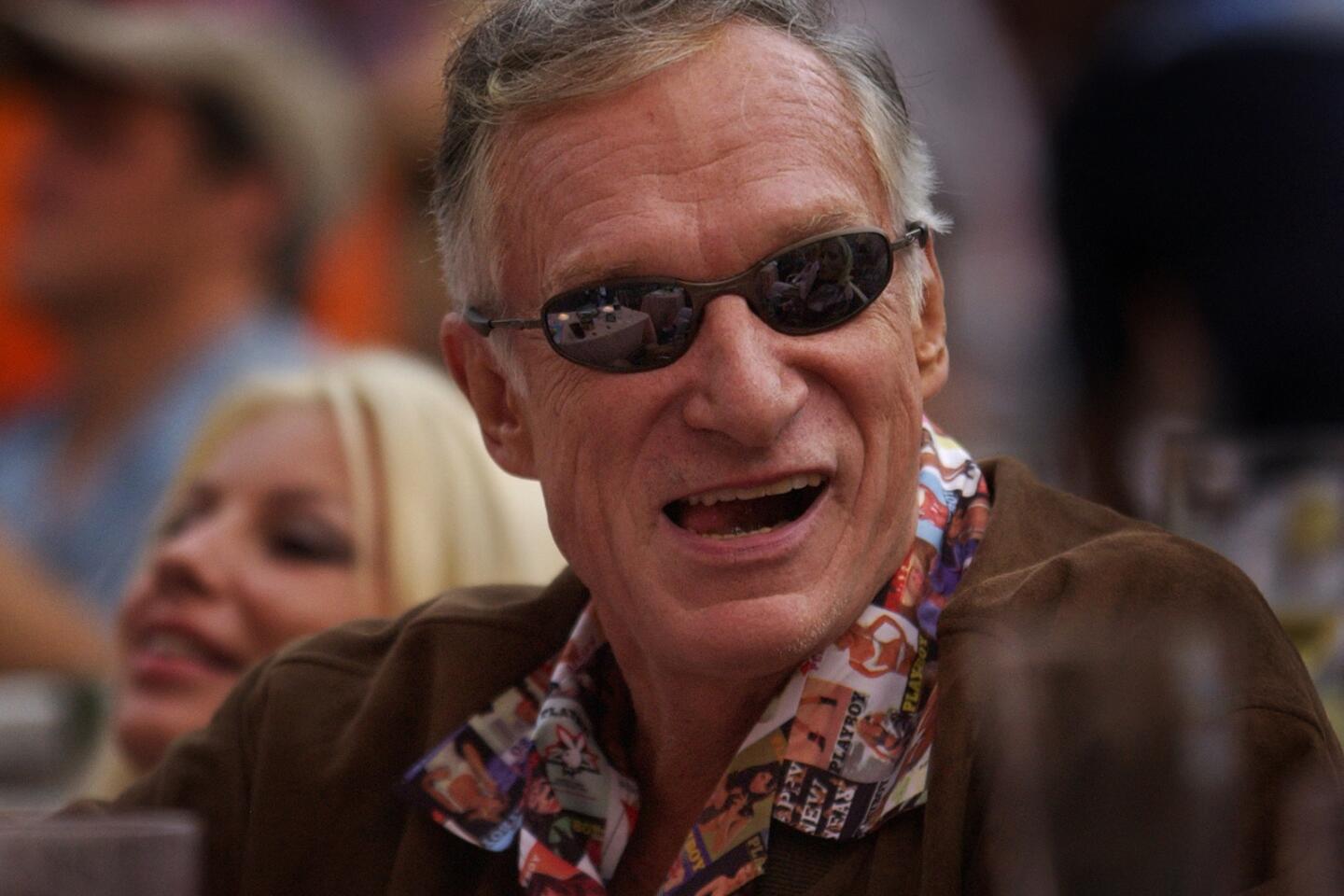

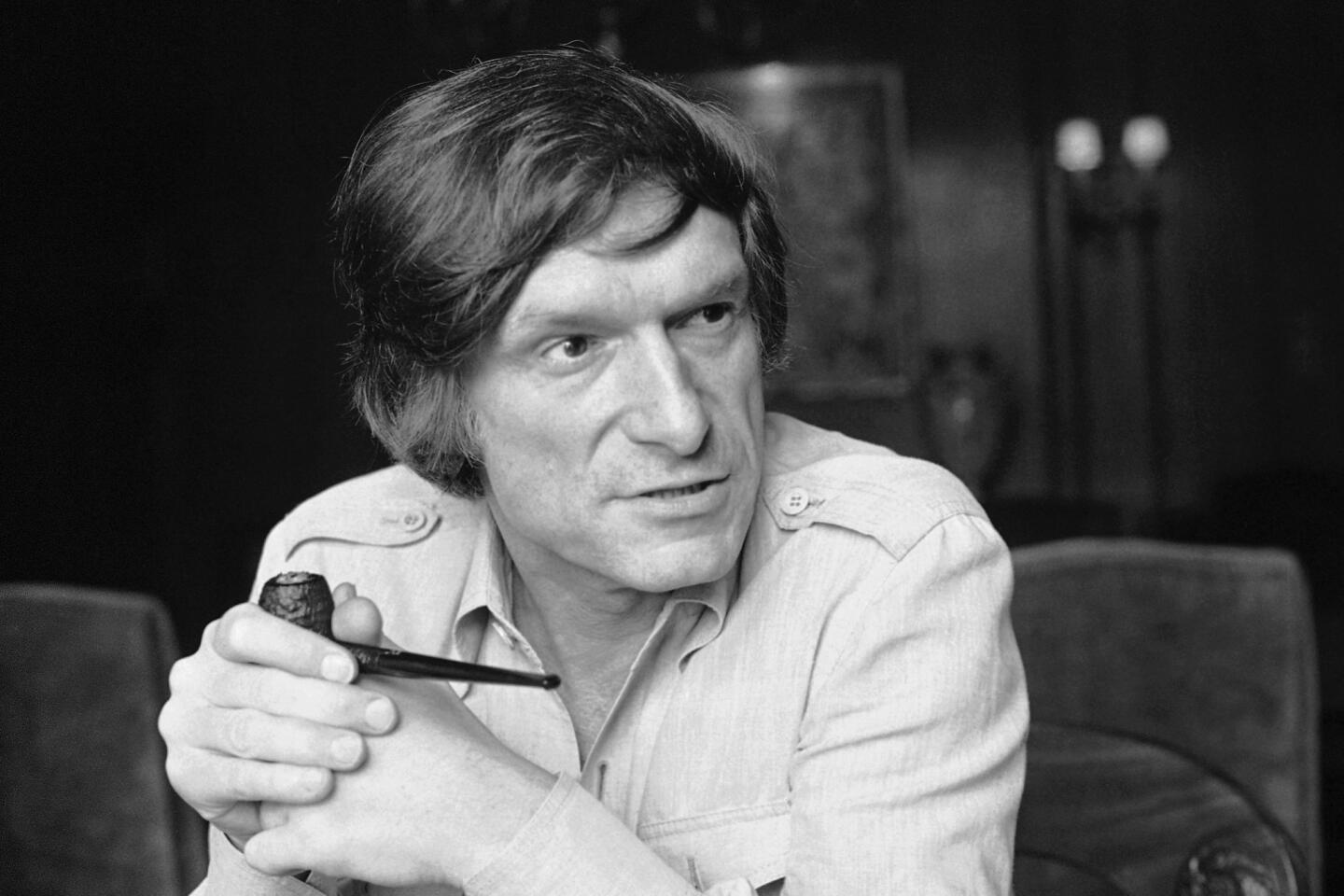

Playboy founder Hugh Hefner, who shook up American morality with an ideal of swinging singlehood, dies at 91

The first issue of Playboy, in December 1952, featured a nude Marilyn Monroe. (Sept. 28, 2017)

- Share via

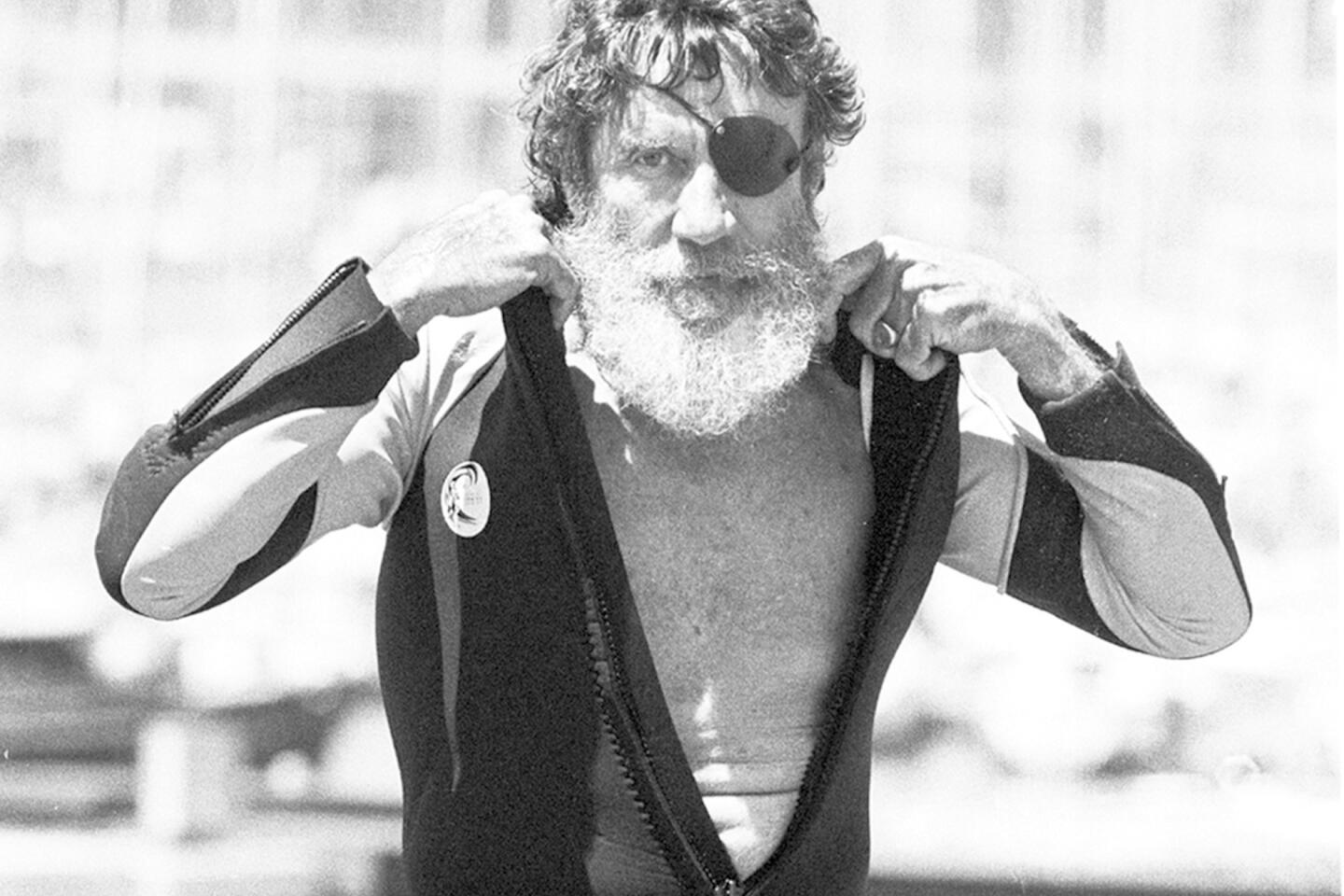

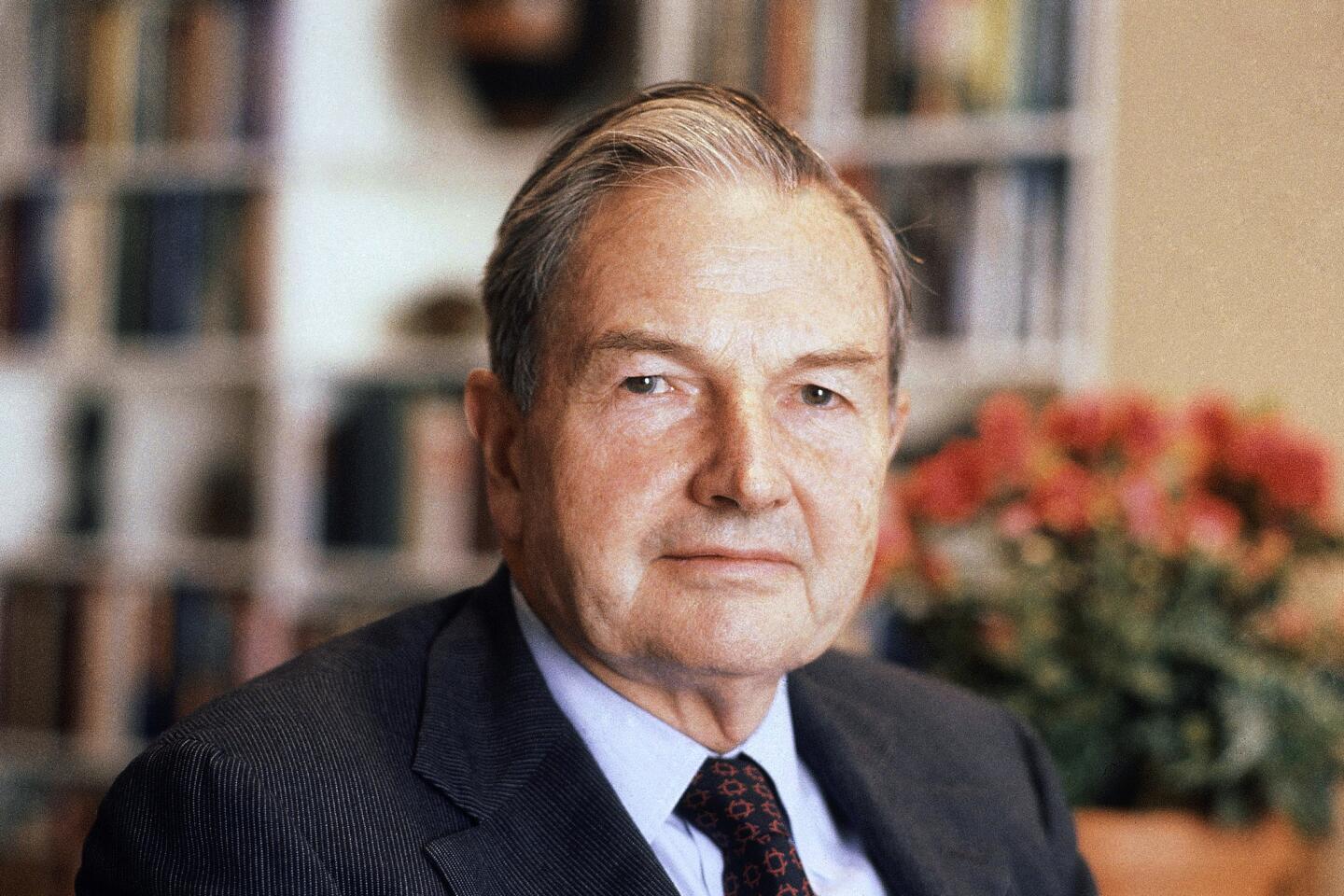

Hugh Hefner, the incurable playboy who built a publishing and entertainment empire on the idea that Americans should shed their puritanical hang-ups and enjoy sex, has died. He was 91.

He died Wednesday of natural causes at his home, the Playboy Mansion, according to Teri Thomerson, a Playboy spokesperson.

Hefner was the founder of Playboy magazine, launched amid the conservatism of the 1950s, when marriage and domesticity conferred social status. Hefner pitched an alternative standard — swinging singlehood — which portrayed the desire for sex as being as normal as craving apple pie. He redefined status for a generation of men, replacing lawn mowers and fishing gear with new symbols: martini glasses, a cashmere sweater and a voluptuous girlfriend, the necessary components of a new lifestyle that melded sex and materialism.

Thus, in Playboy magazine, the upwardly mobile man could ogle pictures of naked women called Playmates, chosen personally by Hefner for their large busts and girl-next-door wholesomeness. Surrounding the titillating visuals were interviews with luminaries from Albert Schweitzer to Malcolm X; short stories by such leading writers as Ernest Hemingway and John Updike; and advice columns on such matters as how to prepare the perfect vodka gimlet or appreciate jazz — all of which lent credence to many men’s claims that they bought the magazine for the articles.

This combination of flesh and intellectuality made Playboy the world’s bestselling men’s magazine and Hefner a millionaire many times over. The venture gave him a pulpit from which to preach the virtues of a postwar revolution in morality and propelled sex into the American mainstream.

“Hefner was the first publisher to see that the sky would not fall and mothers would not march if he published bare bosoms; he realized that the old taboos were going,” Time magazine said in a 1967 cover story. “He took the old-fashioned, shame-thumbed girlie magazines, stripped off the plain wrapper, added gloss, class and culture. It proved to be a sure-fire formula.”

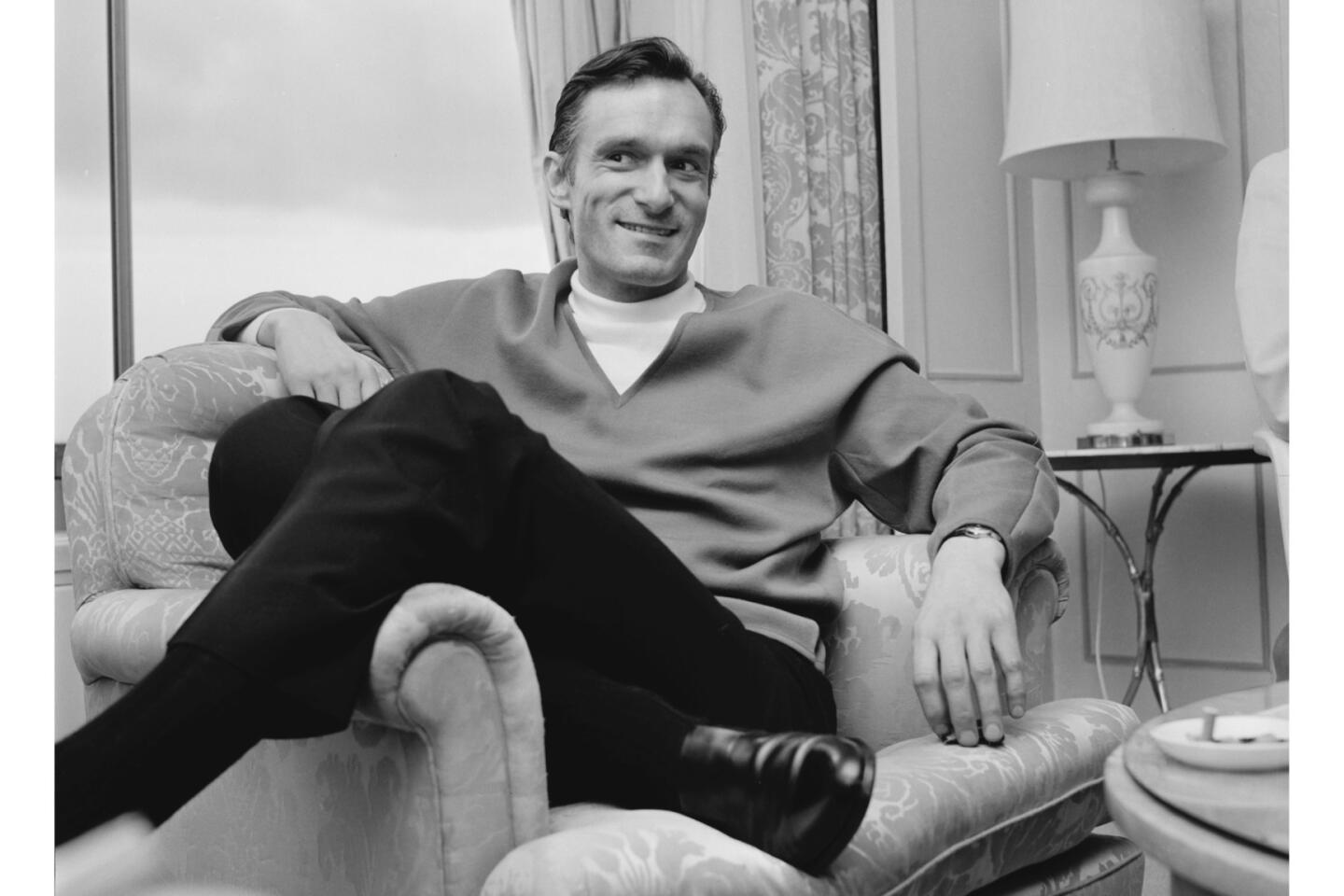

The magazine reflected Hefner himself — or at least the invention that became known the world over as Hefner, or simply Hef. He was the personification of the Playboy ideal, the pajama-loving lord of the grandest bachelor pad on Earth.

“If you don’t swing, don’t ring,” read a brass doorplate at the original Playboy Mansion in Chicago, a 48-room abode where Hefner reveled with bevies of Playmates on a rotating, circular bed. Later, he moved the party to Playboy Mansion West, a six-acre compound above Beverly Hills with 30 rooms, an underground grotto, a staff of 70 and a round-the-clock kitchen attuned to his unconventional schedule — scrambled eggs at, say, 5 p.m., or fried chicken at midnight.

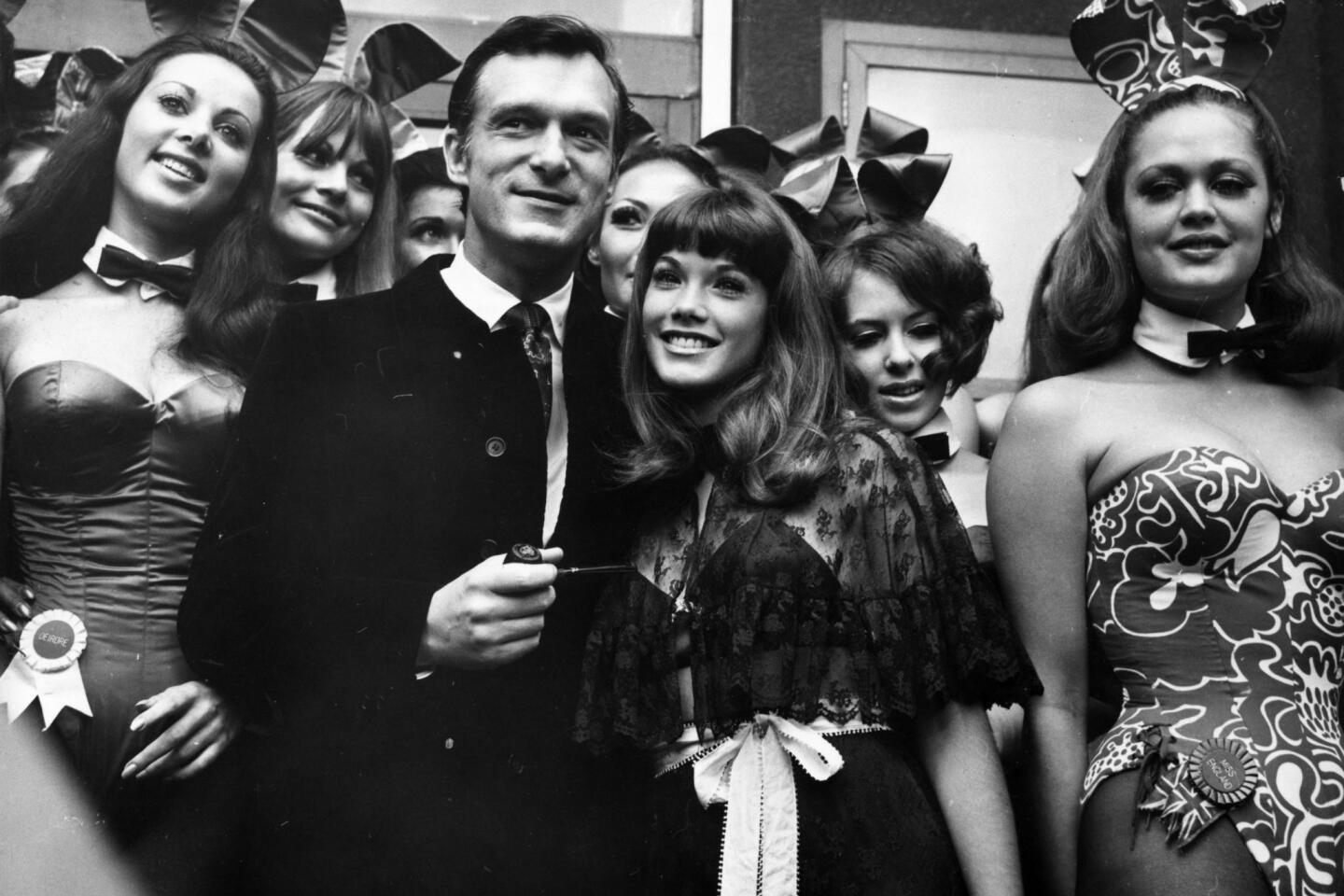

He shared the fantasy not only through the magazine but through a string of Playboy Clubs, where anyone able to pay a modest membership fee could be served food and drinks by “Bunnies” — well-endowed women costumed in rabbit ears, puffy tails and satin corsets so tight that sneezing burst the seams. The black-and-white Bunny logo that adorned the magazine and all manner of merchandise, from cufflinks to cocktail napkins, became a coveted mark of suavity.

Just what the Bunny really stood for — sexual freedom or sexist oppression — became fodder for the cultural wars of the 1960s and ‘70s. Feminist Gloria Steinem fired one of the first shots when she posed as a Bunny and wrote a scathing expose in Show magazine in 1963. “Reading Playboy,” she later said, “feels a little like a Jew reading a Nazi manual.”

Despite such criticism, Playboy’s sales zoomed to 7 million copies a month in the 1970s — but that was a high from which the magazine inevitably would fall. The 1980s brought AIDS, the end of the Playboy clubs, the rise of the religious right, the Meese Commission on Pornography, all of which had a deleterious impact on circulation. Hefner’s image was tainted by the suicide of a trusted associate who overdosed on drugs and his indirect connection to the Dorothy Stratten tragedy, in which the 1980 Playmate of the Year was murdered by her estranged husband.

Then, in 1985, Hefner had a stroke. Though he made a full recovery, he decided, as he put it, to “put down some luggage.” In 1988, he turned over day-to-day operations of his enterprises to his daughter, Christie, while retaining the editorship of the magazine.

The next year, the Playboy-in-Chief did the unthinkable: He got married and settled into monogamy for the better part of a decade.

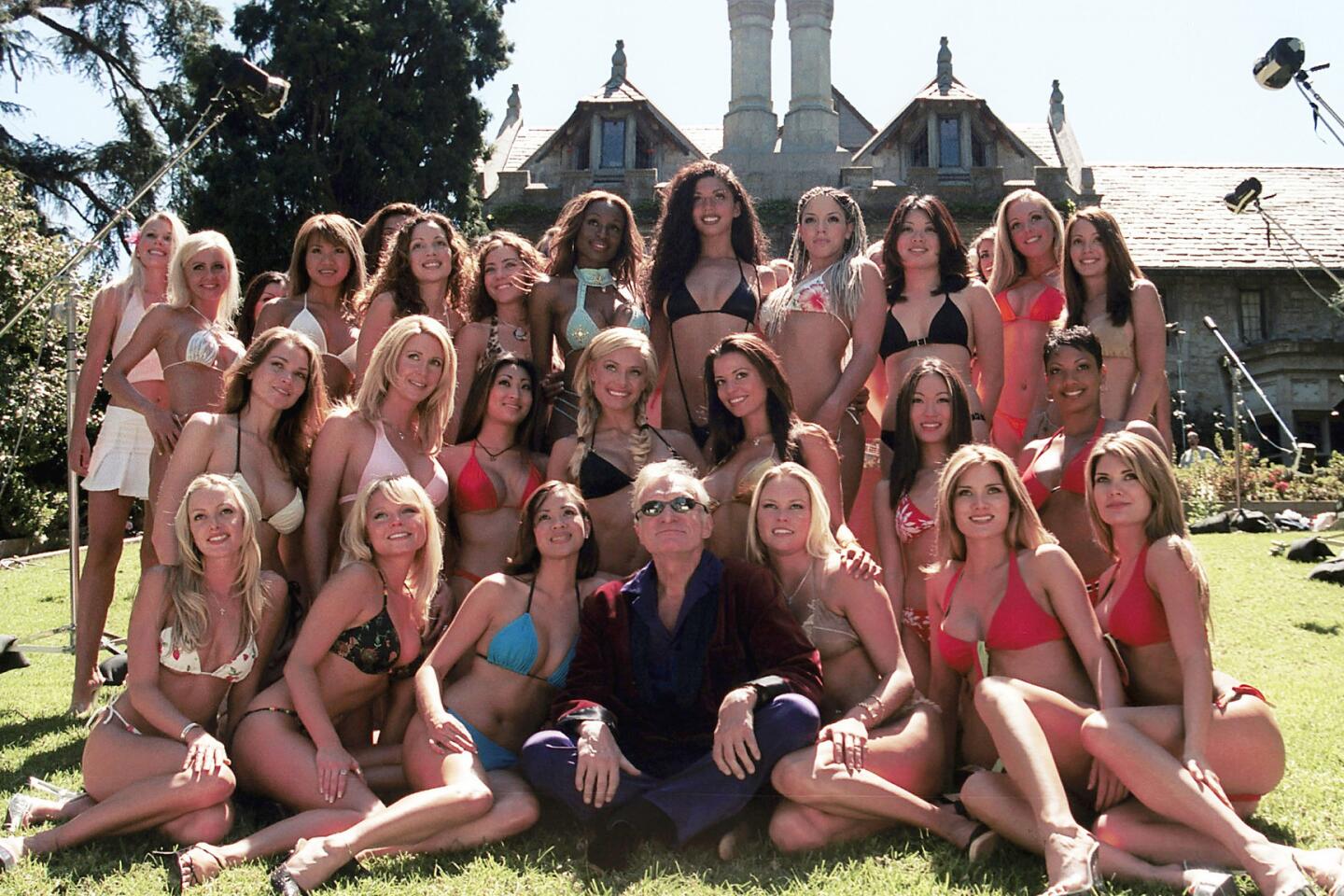

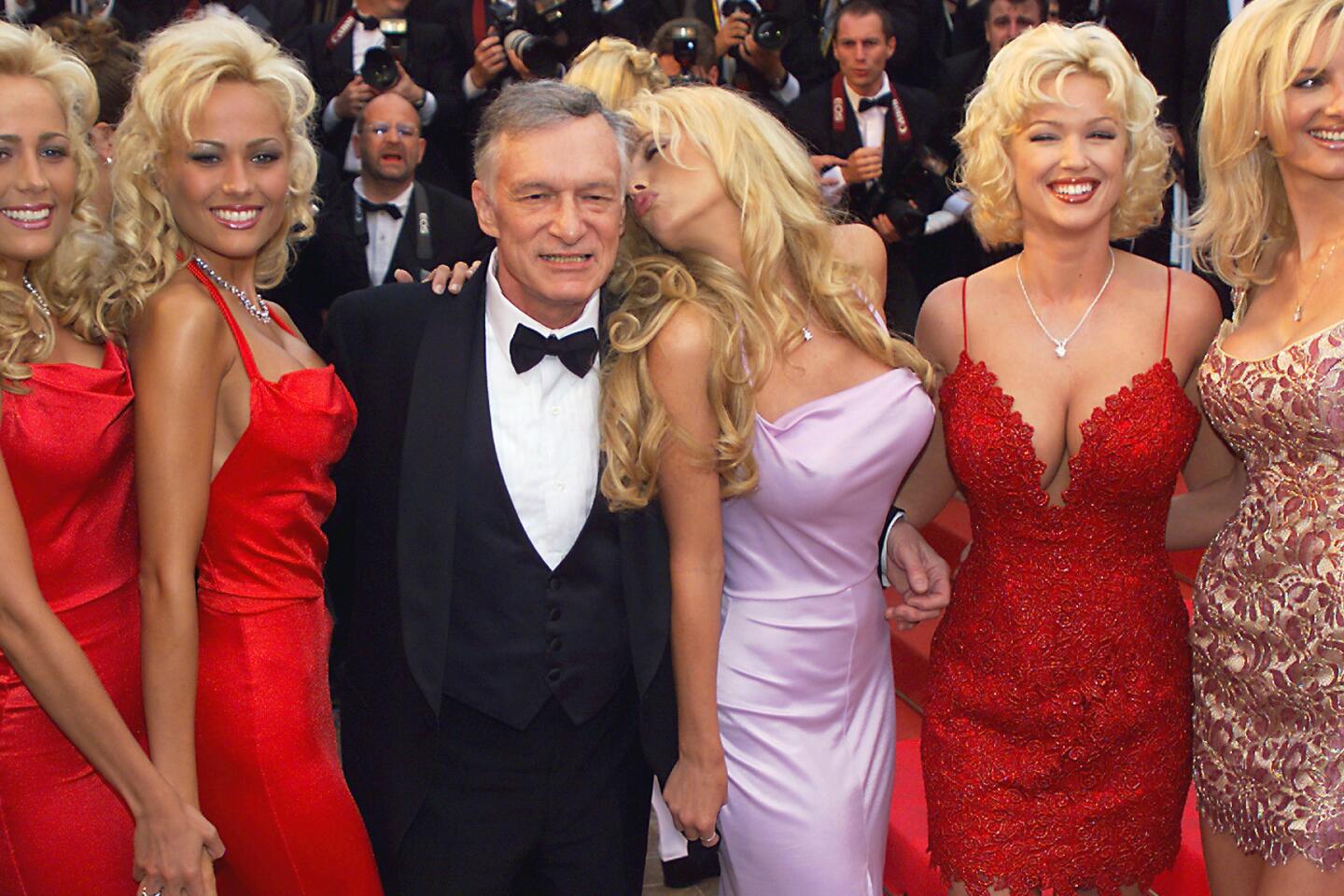

When the marriage collapsed in the late 1990s, the king of sybarites was reborn. He entered the new millennium with a harem of blonde, buxom lovelies all young enough to be his granddaughters. The aging swinger seemed delighted, boasting to a reporter that he had sex “one way or another” everyday, but some observers smirked. “He is so pathetic,” Steinem told the New York Observer in 2005. “Now he’s going around with four young women in their 20s instead of just one…. I feel sorry for him.”

Hefner insisted he was just a relentless romantic, the eternal teenager for whom nothing was sweeter than to have a passionate crush on a girl who liked him back.

“Much of my life has been like an adolescent dream of an adult life,” he told The Times in 1992. “If you were still a boy, in almost a Peter Pan kind of way, and could have just the perfect life that you wanted to have, that’s the life I invented for myself.”

As Hefner often told the story, most of the credit — or blame — belonged to his parents, Grace and Glenn Hefner.

Grace, a former schoolteacher, and Glenn, an accountant whose job kept him away from home for long hours, were devout Methodists, morally strict and emotionally reserved. Such restraint was in the bloodline, their son would later point out. For Glenn Hefner was a direct descendant of William Bradford, one of the English Puritan Separatists who sailed to America on the Mayflower in the early 1600s. The irony was not lost on Hugh Hefner, who would routinely cite this lineage when explaining his rebellion.

“Our family was Prohibitionist, Puritan in a very real sense. Never smoked, swore, drank, danced. Or hugged. Oh, no. There was absolutely no hugging or kissing in my family,” Hefner told the Chicago Sun Times in 2004.

“There was a point in time when my mother, later in life, apologized to me for not being able to show affection. That was, of course, the way she was raised. I said to her, ‘Mom, you couldn’t have done it any better. And because of the things you weren’t able to do, it set me on a course that changed my life and the world.”

Born in Chicago, Hugh Marston Hefner was an introverted youth who loved to chase butterflies. Fond of drawing and writing, he published his own neighborhood newspaper when he was 8 or 9. He was also a daydreamer and dawdler, which brought complaints from his teachers. His worried mother took him to a psychologist, whose tests showed that young Hefner had an IQ of 152 — far above average — but was emotionally immature. The psychologist told Grace Hefner that she could help her son by acting more warmly and sympathetically toward him.

Hefner’s schoolwork improved and he took to drawing with new vigor. He mainly drew semi-autobiographical cartoons about a boy he called “Goo Heffer” who attended “Stinkmuch High.” At Steinmetz High School, he emerged from his shell to become president of the student council and vice president of the literary club.

After graduating in the top quarter of his class, he was drafted into the Army and served stateside from 1944 to 1946. He attended the University of Illinois on the G.I. Bill and majored in psychology while contributing articles and cartoons to the campus paper. He briefly attended graduate school at Northwestern University.

One of the pieces he wrote for the University of Illinois paper was a review of the Kinsey Report, researcher Alfred Kinsey’s pioneering study of male sexual behavior, published in 1948. Hefner wrote: “Dr. Kinsey’s book disturbs me. Not because I consider the American people overly immoral, but this study makes obvious the lack of understanding and realistic thinking gone into the formation of sex standards and laws. Our moral pretenses, our hypocrisy on matters of sex, have led to incalculable frustration, delinquency and unhappiness.”

In 1949 he married Mildred Williams, a college sweetheart with an appealing wholesomeness, but the union was hobbled from the start. During their engagement she had an affair with another man that devastated Hefner, but he refused to call off the marriage. It lasted 10 years, until their divorce in 1959.

Years later he said the experience set him up for a lifetime of promiscuity because “if you don’t commit,” he told The Times in 1994, “you don’t get hurt.” He said it also showed him what was wrong with traditional attitudes towards sex: “Thinking sex is sacred is the first step toward really turning it into something very ugly,” he said on another occasion.

Although he wanted to be a cartoonist, Hefner was unable to sell any of his strips to newspapers. He also wanted to start his own magazine, but he lacked capital. To pay the bills, he took a job in the personnel department of a carton printing and manufacturing company in Chicago but quit over its policy of rejecting applicants who were black, Jewish or had ethnic-sounding names. His next job was writing advertising copy for the department store Carson, Pirie, Scott and Co. He continued to draw cartoons on the side, including a series about Chicago that he self-published under the title “That Toddlin’ Town.” He sold about 5,000 copies and became a minor local celebrity.

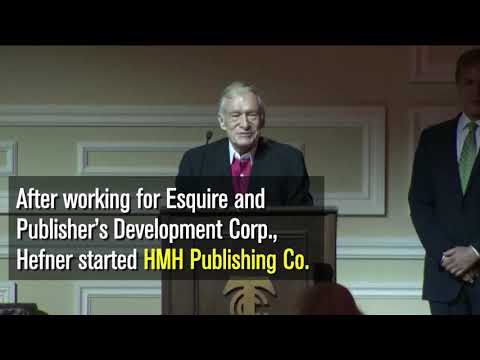

In 1951, he applied to Esquire magazine and was hired as a promotional copywriter at $40 a week. When Esquire moved most of its operations to New York, he quit and took a sales job at Publisher’s Development Corp., a Skokie, Ill., firm that published a dozen trade and “nudie” magazines. A colleague, Vince Tajiri, who would become Playboy’s photo editor, told Hefner biographer Russell Miller that Hefner “was very immature for his age. He was totally unsophisticated, but he had this obsession with sex. When he had nothing else to do he would draw pornographic cartoons of Blondie and Dagwood.”

Hefner soon advanced to a higher paying position as circulation promotion director of Children’s Activities magazine. By then he had become the father of Christie Ann; his future successor as head of the Playboy empire, who was born in 1952. A second child, David, was born in 1955.

Saddled with family responsibilities and a less-than-thrilling job, Hefner grew depressed. “I remember standing on a bridge, looking out at Lake Michigan and thinking my life was not going anywhere,” he recalled in Time magazine in 2005. “I felt as if I had successfully become my parents. Tears filled my eyes.”

The incident spurred him to start HMH Publishing Co. with $600 borrowed from two banks and $3,000 from friends and family. He was blissfully ignorant of the challenges ahead. “If I had known then what I know now,” he told Brady, “I doubt if I would have even tried. But once I had made up my mind, I worked on the idea with everything I had, and for the first time in my life I felt truly free. It was like a mission — to publish a magazine that would thumb its nose at all the phony puritan values of the world in which I had grown up.”

By then — 1953 — the Kinsey report on female sexuality had come out. With findings that pointed to the prevalence of premarital and extramarital sex, it provided Hefner with confirmation of his growing belief that women were becoming more comfortable with their own sexuality.

Working out of his apartment with a minimal staff — art director Art Paul and sales manager Eldon Sellers — Hefner labored around the clock to assemble the first issue. After considering the name Stag Party, Hefner took Sellers’ suggestion and went with Playboy instead. Hefner proposed a tuxedoed rabbit as a “cute, frisky, and sexy” logo, which Paul designed in half an hour.

Hefner was so unsure of the magazine’s prospects that he did not put a date on the first issue, thinking it might take some time to sell all the copies. He kept his name out of that first issue, too, in case the enterprise flopped. In its tone, however, the magazine oozed confidence. “We want to make clear from the very start, we aren’t a ‘family magazine,’“ Hefner wrote in the first editorial. “If you’re somebody’s sister, wife or mother-in-law and picked us up by mistake, please pass us along to the man in your life and get back to your Ladies Home Companion.”

Playboy, he wrote a short while later, was meant for any sort of man on the rise, from an engineer to a university professor, but the ideal reader “must be an alert man, an aware man, a man of taste, a man sensitive to pleasure, a man who — without acquiring the stigma of the voluptuary or dilettante — can live life to the hilt. This is the sort of man we mean when we use the word playboy.”

A big chunk of Hefner’s meager budget for the first issue was consumed by the pictorial: He paid a Chicago calendar maker $500 for photographs of Marilyn Monroe with “nothing but the radio on.” That first issue, in December 1953, also featured a cartoon by Hefner, party jokes, black-and-white pictures of nude sunbathers in California, articles on football and the Dorsey brothers, and fiction by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Ambrose Bierce, which cost Hefner nothing because they had passed into public domain.

He quickly sold out the complete run of 70,000 copies. By the fourth issue, production had moved from Hefner’s apartment to a rented office across the street from a Catholic cathedral. He moved a bed into the office, a convenience for a man who often worked 36 hours straight (and was having an affair with a nurse from a nearby hospital.) By the first anniversary, Playboy’s circulation was a healthy 175,000 copies. By the fifth anniversary, it had surpassed Esquire, with nearly 900,000 copies sold each month. In the early 1970s circulation would peak to 7 million.

It took more than a year for Hefner to devise the most popular feature of the magazine — the photo layout that would christen 12 women a year Playmates of the Month.

In the first issues he had relied on professional nude models, who exuded a certain world-weariness. For the July 1955 issue, he recruited one of his girlfriends, 20-year-old Playboy subscription department employee Charlaine Karalus. He called her Janet Pilgrim for publication purposes. She was posed at a dressing table wearing a bosom-baring negligee. In the background was the shadowy figure of a tuxedoed man — Hefner himself.

Accompanying the layout was a story that introduced Pilgrim as an office worker who had never before taken off her clothes for the camera. There was also a more demure photo showing her in business attire discussing “the magazine’s rising circulation” with the debonair publisher. The intent was to portray the Playmate as the girl next door, unthreatening but frolicsome, and suggest that the world was full of such appealing women. They could be, Hefner wrote in the magazine, “the new secretary at your office, the doe-eyed beauty who sat opposite you at lunch yesterday, the girl who sells you shirts and ties at your favorite store.”

This conception of the Playmate provided the foundation for the magazine’s enduring success. Hefner became, according to Talese, “the first man to become rich by openly mass marketing masturbatory love through the illusion of an available alluring woman For the price of the magazine, Hefner gave thousands of men access to an assortment of women who in real life would not look at them.”

Readers’ ecstatic responses to Pilgrim convinced Hefner that he had found a winning formula. For the succeeding Playmates, the layouts amounted to a carefully constructed seduction, “almost a study in sexual foreplay, building from clothed to semi-clothed poses,” Brady, the former Playboy editor, wrote in “Hefner,” a 1974 biography. “The excitement would mount as the Playmate revealed tantalizing glimpses of her obvious charms. And finally, quite literally bursting forth with its foldout format, the climax: the centerfold showing as much of her body as possible.”

Hefner would not show everything, believing some modesty would bolster his magazine’s chances for success. Thus, he banned pubic hair and genitalia, airbrushing away all traces. He held to these strictures until 1971, when competition from Bob Guccione’s Penthouse convinced him to allow more graphic poses of Playmates. The field grew more crowded and explicit with Larry Flynt’s Hustler, which began publishing in 1974.

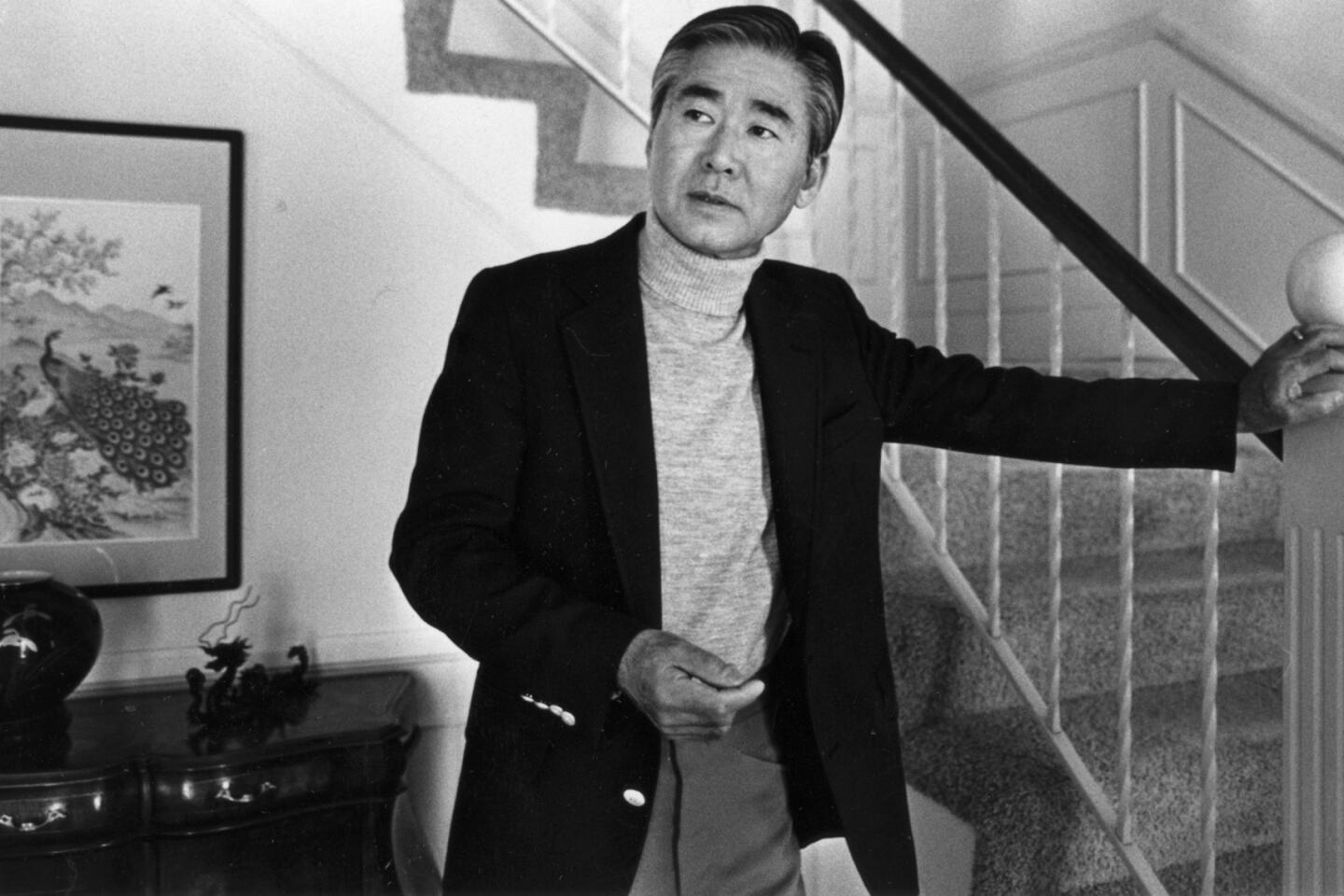

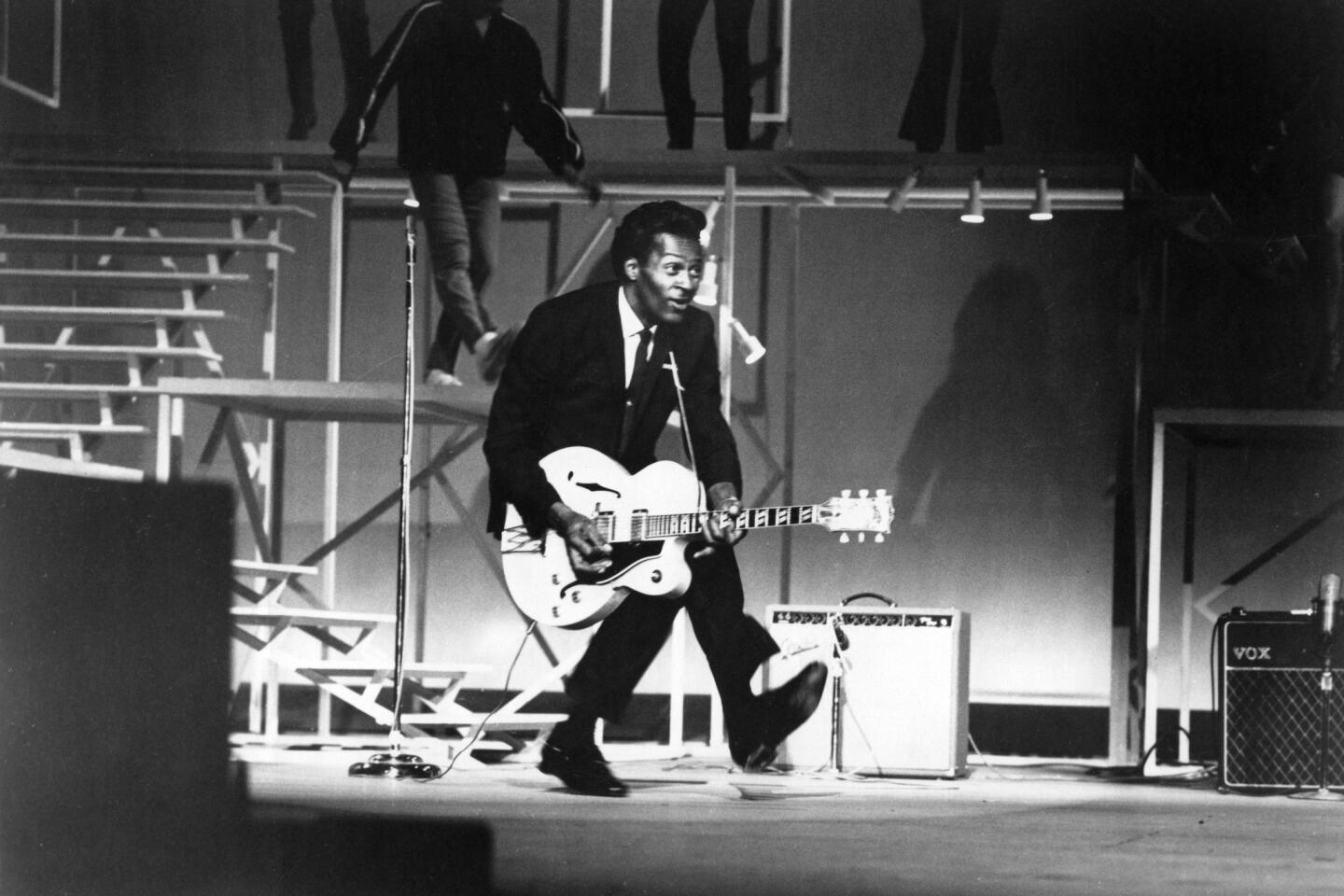

The enterprising Hefner had by then expanded his empire in several directions. He produced and hosted “Playboy’s Penthouse” (1959), a television talk-variety show staged as a party in a sophisticated bachelor pad, where the guests were figures like comic Lenny Bruce and musical legend Nat King Cole. It was followed a decade later by a similar show, “Playboy After Dark” (1969).

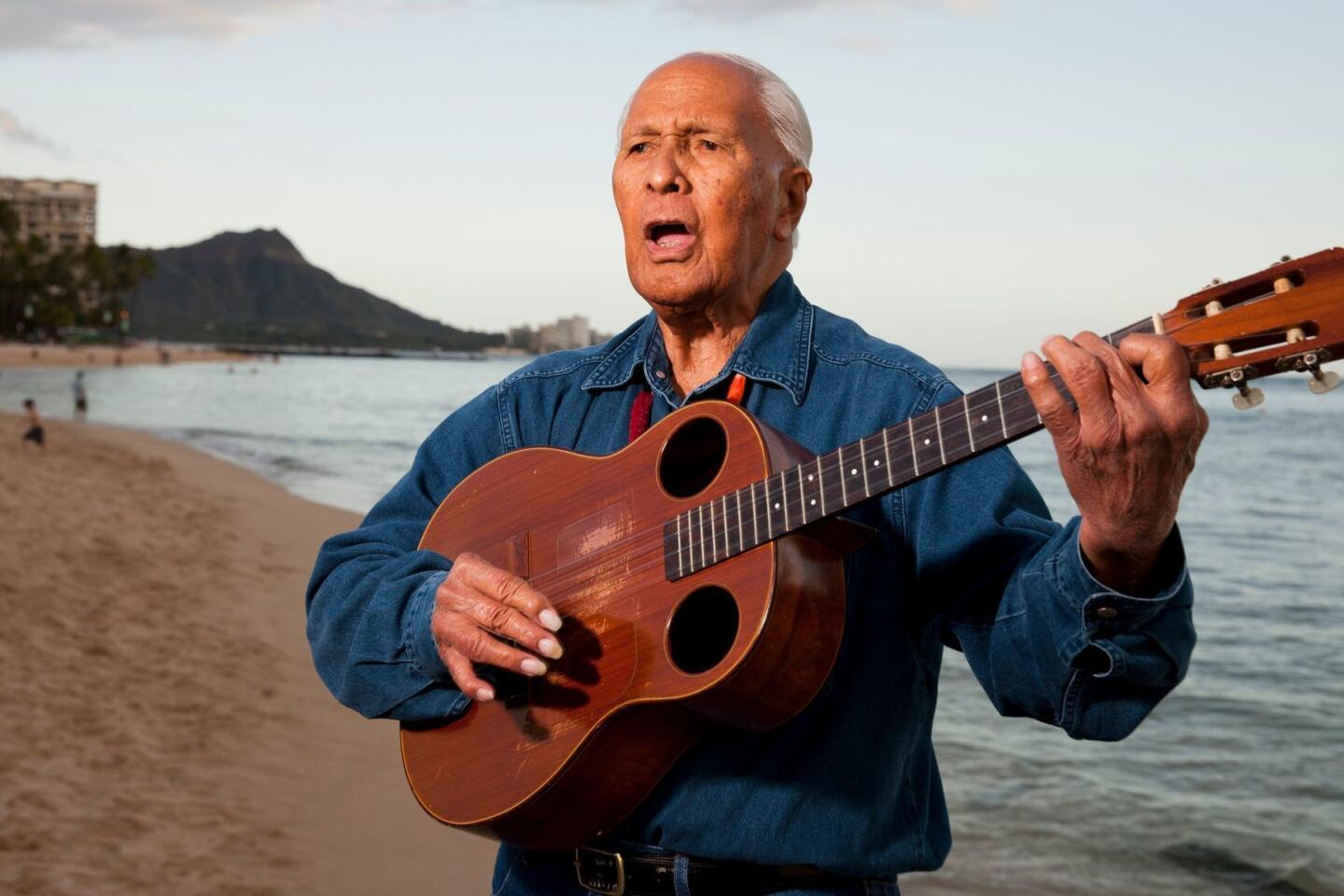

A jazz aficionado, Hefner held the first Playboy Jazz Festival in Chicago in 1959 to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the magazine. Seventy thousand attended the concert at Chicago Stadium, where the lineup included Stan Kenton, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Dave Brubeck, Oscar Peterson, Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie, Louis Armstrong and Ella Fitzgerald. Critic Leonard Feather proclaimed it “the greatest single weekend in the history of jazz.”

The second festival was held at the Hollywood Bowl in 1979 to mark Playboy’s 25th anniversary, and it has been an annual event there ever since.

In 1960, the first Playboy Club opened in Chicago. Over the next three decades, the enterprise grew into a chain of 35 clubs and three resorts, including casinos, stretching from Los Angeles to the Bahamas. They became important jazz venues and gave exposure to such comics as Bruce and Dick Gregory, the first black comic to play a white circuit. Hefner insisted on integrating the clubs in the South, buying back franchises whose owners balked at hiring black Bunnies.

But the clubs, like the magazine, became a lightning rod for feminist dissent. Steinem’s 1963 expose portrayed the Bunnies as victims of exploitation, who were poorly paid, required to undergo pre-employment gynecological exams (eliminated in the wake of Steinem’s article), and tailed by private detectives checking for minor costume infractions and other no-no’s, such as failing to laugh when a comic was performing.

In a 1983 postscript to the article, Steinem concluded grimly that “all women are Bunnies.” By the end of the 1980s, there were no more Playboy Clubs in the U.S. (The company resurrected the concept in 2006 with a new Playboy Club at the Palms Casino and Resort, but handed management of the venture to the casino.)

In 2004, when the magazine celebrated its 50th anniversary, its circulation of about 3 million was less than half what it had been in the 1970s, outdone by brasher magazines and Internet porn sites, and the numbers would continue to decline. In 2009, Christie Hefner stepped down as chief executive. In 2010, concerned about the Playboy brand and the magazine’s editorial direction, Hefner, who still owned 70 percent of the company’s Class A stock, attempted to take the company private in partnership with a Michigan private equity firm.

Part of what had set Playboy apart from the competition were its intellectual and social aspirations. It was a skin magazine with a philosophy.

Hefner outlined his lofty ideals in a series of 25 columns in the early 1960s that ran as “The Playboy Philosophy.” With references as various as Caesar, Darwin and Charlie Chaplin, he used the columns to respond to critics who had expressed alarm at Playboy’s growing influence. “Although far too long and maddeningly repetitive,” author Malcolm Boyd wrote in 1970, “the philosophy also has pages that crackle with a concern for human justice and an underlying idealism that cuts against the popular image of the archetypal ‘playboy.’“

Many of the critics were members of the clergy, who wrote letters, articles and sermons on what they had begun to perceive as the Playboy menace. Hefner quoted some of their comments in his columns, such as those of Unitarian minister John A. Crane, who wrote: “Not only does Playboy create a new image of the ideal man, it also creates a slick little universe all its own, creates what you might call an alternative version of reality in which men may live in their minds. It’s a light and jolly kind of universe, a world in which a man can be forever carefree, like Peter Pan, a boy forever and ever. There are no nagging demands and responsibilities, no complexities or complications.”

Hefner’s response summed up the philosophy this way: “Playboy,” he wrote in the first column, “has always dealt with the lighter side of contemporary life, but it has also -- tacitly and continuously -- tried to see modern life in its totality. We hope that Playboy has avoided taking itself too seriously. We know that we have always stressed — in our own way — our conviction of the importance of the individual in an increasingly standardized society, the privilege of all to think differently from one another and to promote new ideas, and the right to hoot irreverently at herders of sacred cows and keepers of stultifying tradition and taboo.”

Thus, during the Cold War Playboy ran controversial profiles of Communist-leaning Chaplin and blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo. Other articles over the decades tackled such sensitive topics as abortion, birth control and sex education. Columns such as the Playboy Advisor frankly addressed readers’ questions about orgasm, masturbation, penis size and other sensitive matters.

Playboy also ran the work of distinguished fiction writers, including Jack Kerouac and Norman Mailer. A version of Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451” first appeared in the pages of Playboy.

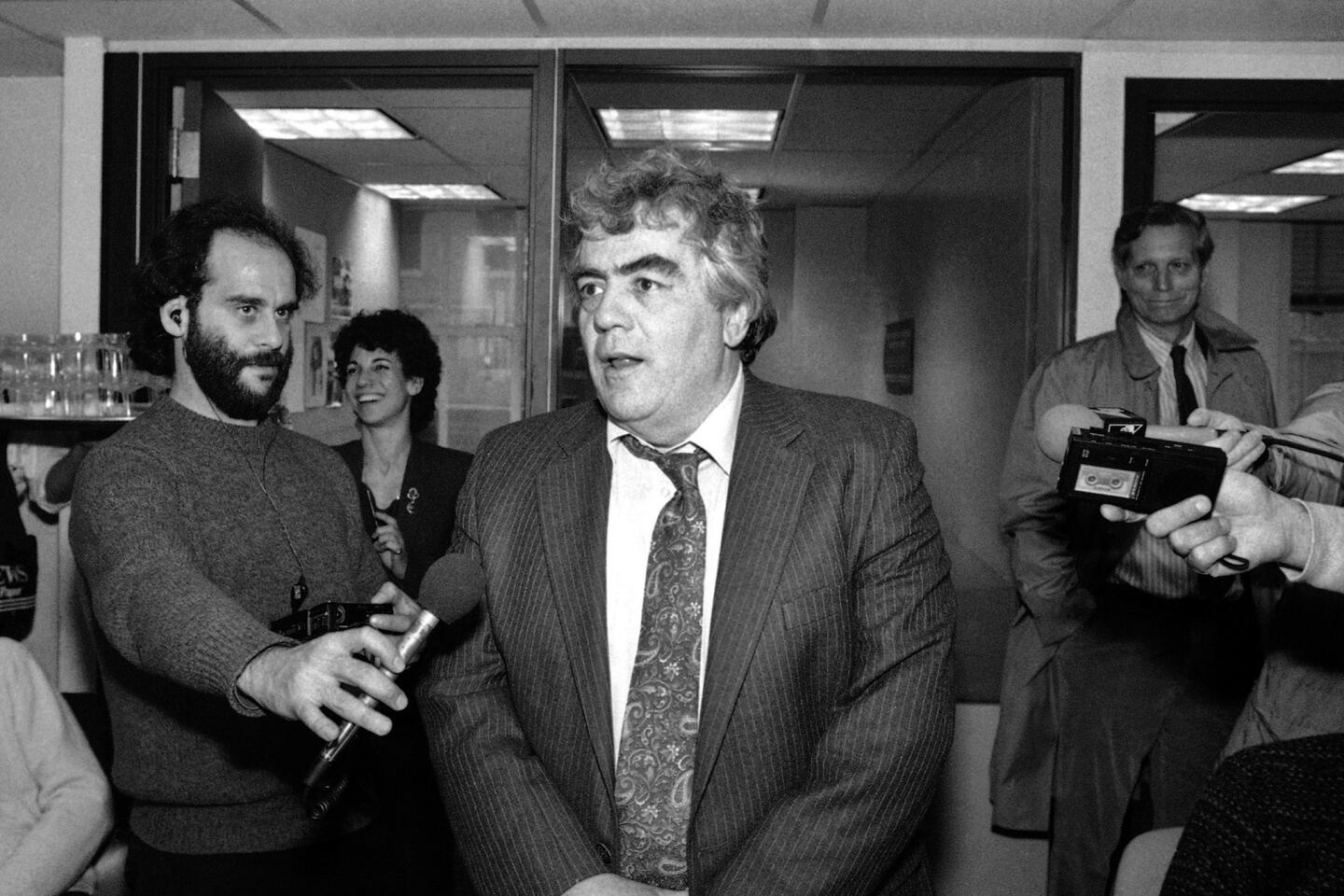

The magazine launched the career of “Roots” author Alex Haley, who tackled a number of noteworthy figures for the Playboy Interview, including Miles Davis and Malcolm X. (The latter piece led Haley to write “The Autobiography of Malcolm X,” the influential 1965 book based on interviews with the Nation of Islam leader, who was assassinated the same year.)

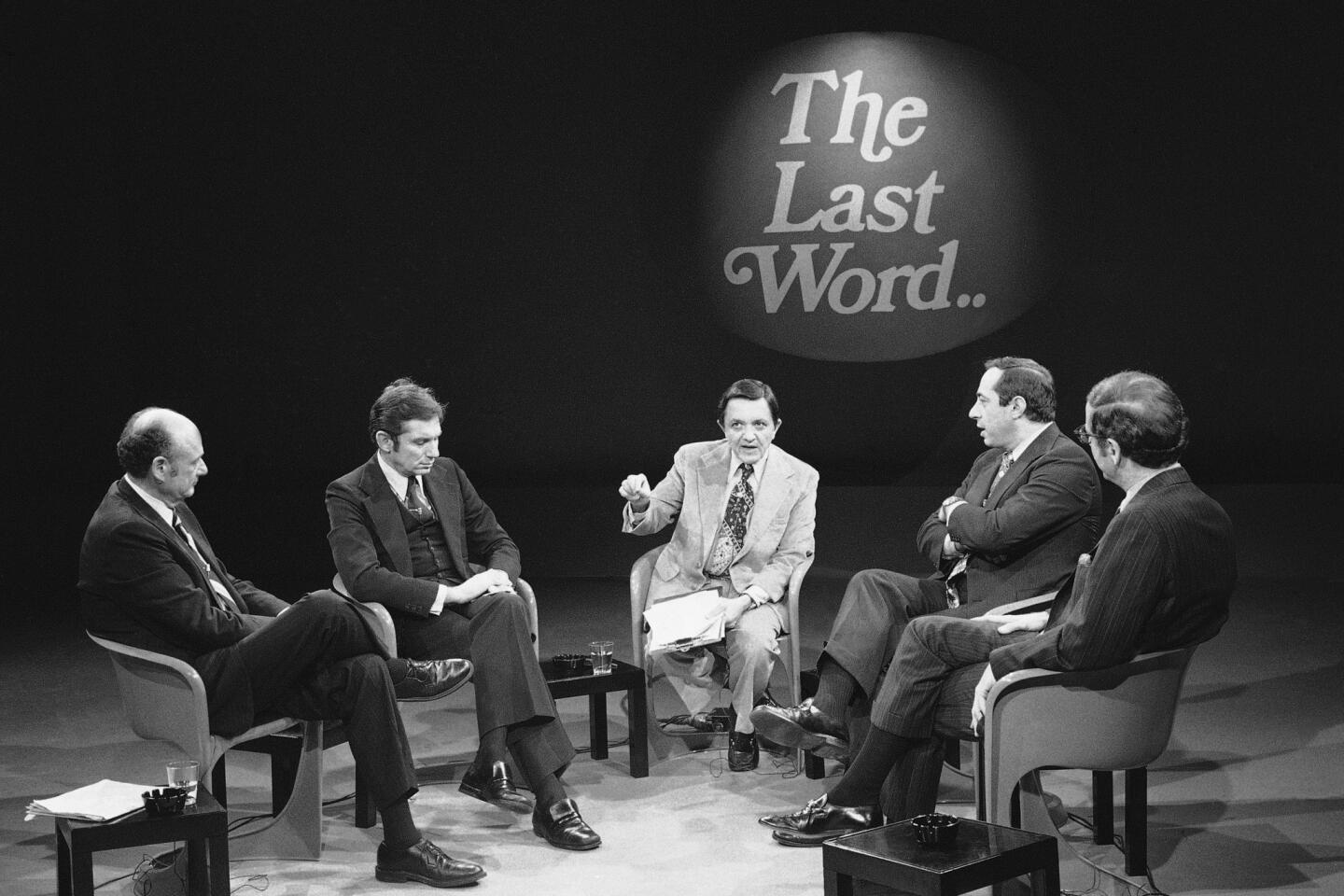

The Playboy Interview often made news, such as in 1976 when Jimmy Carter, on the eve of his victory over then-President Gerald Ford, admitted he had lusted for women other than his wife. Playboy’s serialization of Woodward and Bernstein’s “All the President’s Men,” their 1974 book about the Watergate investigation, was another milestone.

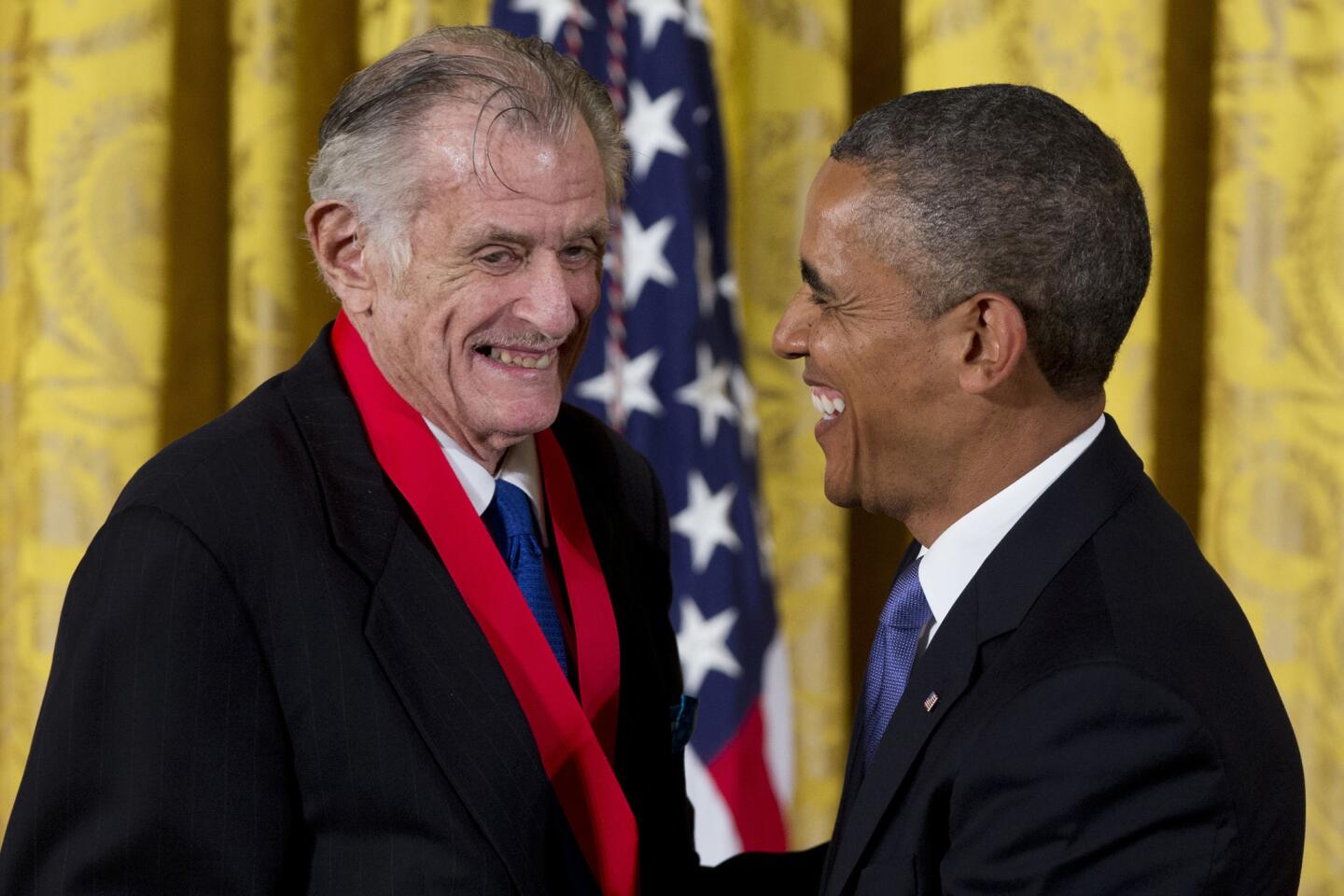

Hefner, the would-be cartoonist, also gave Jules Feiffer his first national exposure. Feiffer, who became known for his minimalist drawings and edgy urban characters, later said Hefner was the best cartoon editor he’d ever had.

Henry Luce, who founded the Time-Life empire and ran it for more than 40 years, was a giant of magazine journalism, but he did not personify his creations. Hefner did. Inducted into the American Society of Magazine Editors Hall of Fame in 1998, he was arguably the nation’s most famous magazine editor-publisher, whose lifestyle was the greatest marketing tool Playboy could ever have.

He admitted journalists to his bedroom, central to which was that bed. More than seven feet in diameter, it was, Tom Wolfe once wrote, “the biggest roundest bed in the history of the world.” Strategically installed above it was a $40,000 videotaping system, maintained by a full-time engineer. “Who knows when something very beautiful might happen in this bedroom?” he said by way of explanation to an awestruck Wolfe, who wrote about his visit to the Chicago Playboy mansion in a classic article reprinted in his 1965 book “The Pump House Gang.”

Surrounded by outrageous luxuries — including a bowling alley, a steam room, a dormitory for Bunnies, and refrigerators in nearly every room stocked with his favorite beverage, Pepsi — Hefner hardly left the mansion for several years in the 1960s. He directed his empire from his plushly carpeted bedroom, where the world came to him at his convenience. If he had to leave town, he took the Big Bunny, a $4-million DC-9 with a conspicuous paint job: all black except for a white bunny on the tail. The Big Bunny had a big bed, too, of course, equipped with seat belts. When he deplaned, Mr. Playboy always had a few shapely women close beside him.

In 1988 he married former Playmate Kimberley Conrad and and had two children with her. When they separated a decade later, he jumped again into plural romance (“[I]t was like Elvis Presley had suddenly shown up at a supermarket,” he told Los Angeles magazine in 2010) with a trio of like-named companions — Sandy, Mandy and Brande. They were succeeded by what Hefner’s website described as a “rotating girlfriend supergroup” of three to six young women, who lived at the mansion and accompanied him on the party circuit. He featured three for the 2005 debut of an E! channel reality show called “The Girls Next Door,” which one critic called “a spectacularly brainless excursion” into life at Playboy Mansion West, the Holmby Hills estate where he lived for more than three decades. In 2009 he sold the adjoining estate where Conrad and their two children lived and filed for divorce.

He kept his medicine cabinet stocked with Viagra, the frequent use of which he believed caused some hearing loss. But he apparently regarded that side effect as a small price to pay for the libertine lifestyle he popularized. “I’m one of a handful of people who most represent the sexual revolution,” Hefner once told writer Boyd. “Not that I invented sex, of course, but I’ve done more than almost anyone to promote the idea of sexual freedom.”

He advanced the cause not only through his magazine and group dating practices but through his philanthropy. The Playboy Foundation has distributed more than $15 million since 1965 to support a variety of progressive activities, including early funding for the Masters and Johnson Institute to train sex therapists.

Through the foundation, Hefner also aided feminist causes. It supported the National Abortion and Reproductive Rights Action League as well as cases that led to Roe vs. Wade, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion.

He considered himself a friend of the women’s movement. “Playboy,” he once said, “treats women — and men, too, for that matter — as sexual beings, not as sexual objects. In this sense, I think Playboy has been an effective force in the cause of female emancipation.” It may not be coincidence that Playboy reached its highest circulation in 1972, the year that Ms. Magazine was launched.

Hefner “played an important role in attempting to escort American consciousness out of what was still an embarrassingly puritanical set of publicly expressed, if not privately practiced. attitudes toward sexuality,” Robert Thompson, a Syracuse University professor and past president of the International Popular Culture Assn., told The Times in 2005. “His impact upon the First Amendment and the women’s movement was substantial.”

But Thompson, along with other critics, said Hefner’s influence was also pernicious: He helped give rise to the consumer culture through Playboy’s linkage of sex with material goods. “One can look back at those old Playboy pictorials and find that they eroticized the products surrounding the women as much as they eroticized the women,” Thompson said.

Journalist and social critic Barbara Ehrenreich perceived another aspect of Hefner’s and Playboy’s influence. “Playboy’s visionary contribution,” she wrote in a 1984 essay, “was to give the means of status to the single man: not the power lawn-mower, but the hi-fi set in mahogany console; not the sedate, four-door Buick, but the racy little Triumph; not the well-groomed wife, but the classy companion who could be rented (for the price of drinks and dinner) one night at a time.”

Hefner readily admitted that he was not an emancipated male. After his transformation in the 1950s from married father of two to Playboy-in-Chief, he never dated women his own age or who had their own high-powered careers. “I’m not looking for a female Hugh Hefner,” he said. He may have spearheaded the sexual revolution, but in his private realm, he preferred the status quo.

In December 2010 he became engaged to his girlfriend of two years, Crystal Harris, who at 24 was 60 years his junior, but she called off the wedding six months later.

Hefner will be laid to rest in a Westwood crypt beside Marilyn Monroe, whose nude pictures helped launch Hefner into history. As he told The Times in 2009, “Spending eternity next to Marilyn is too sweet to pass up.”

ALSO

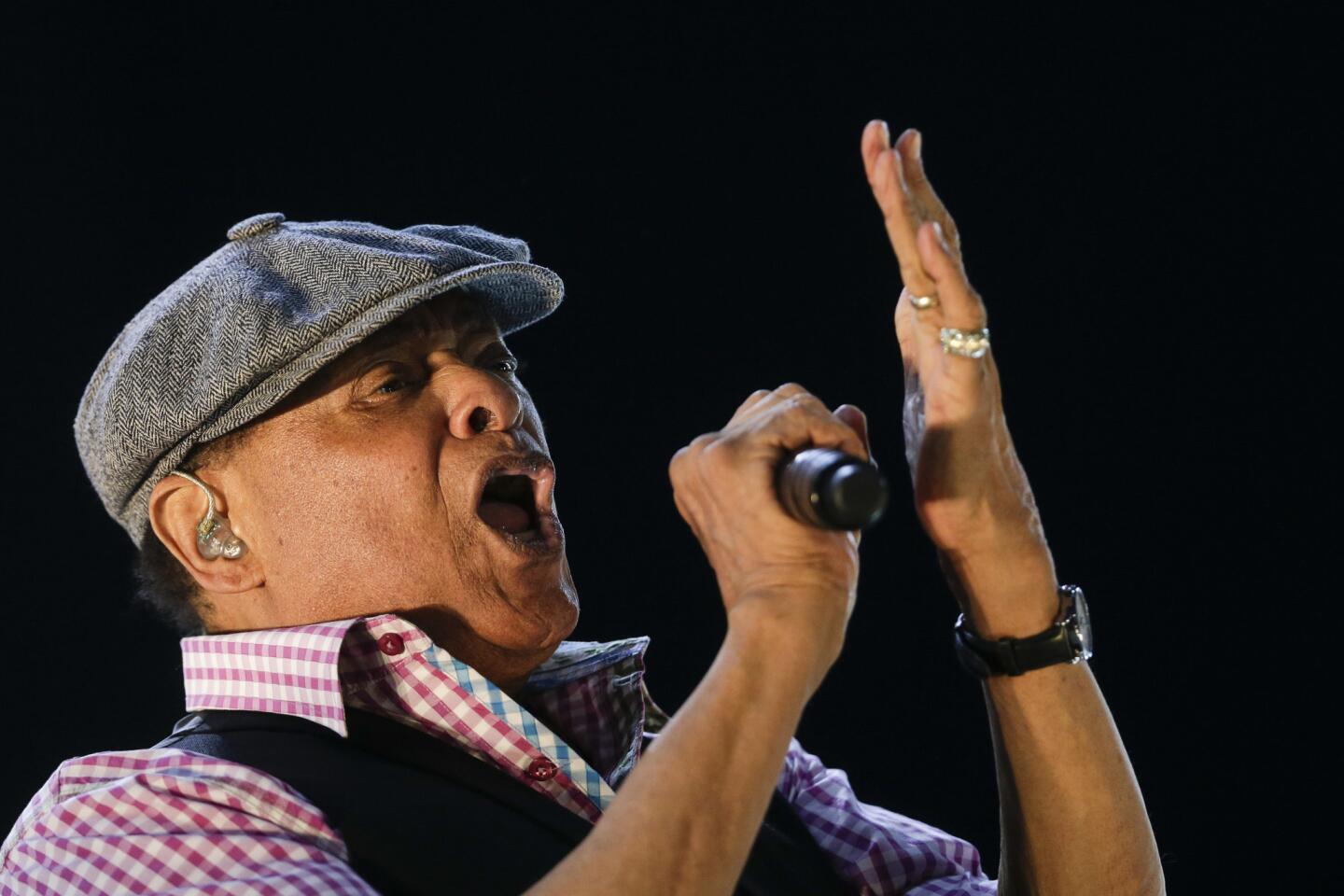

Soul singer Charles Bradley, a powerful voice of joy, dies at 68

Jake LaMotta, boxer profiled in ‘Raging Bull,’ dies at 95

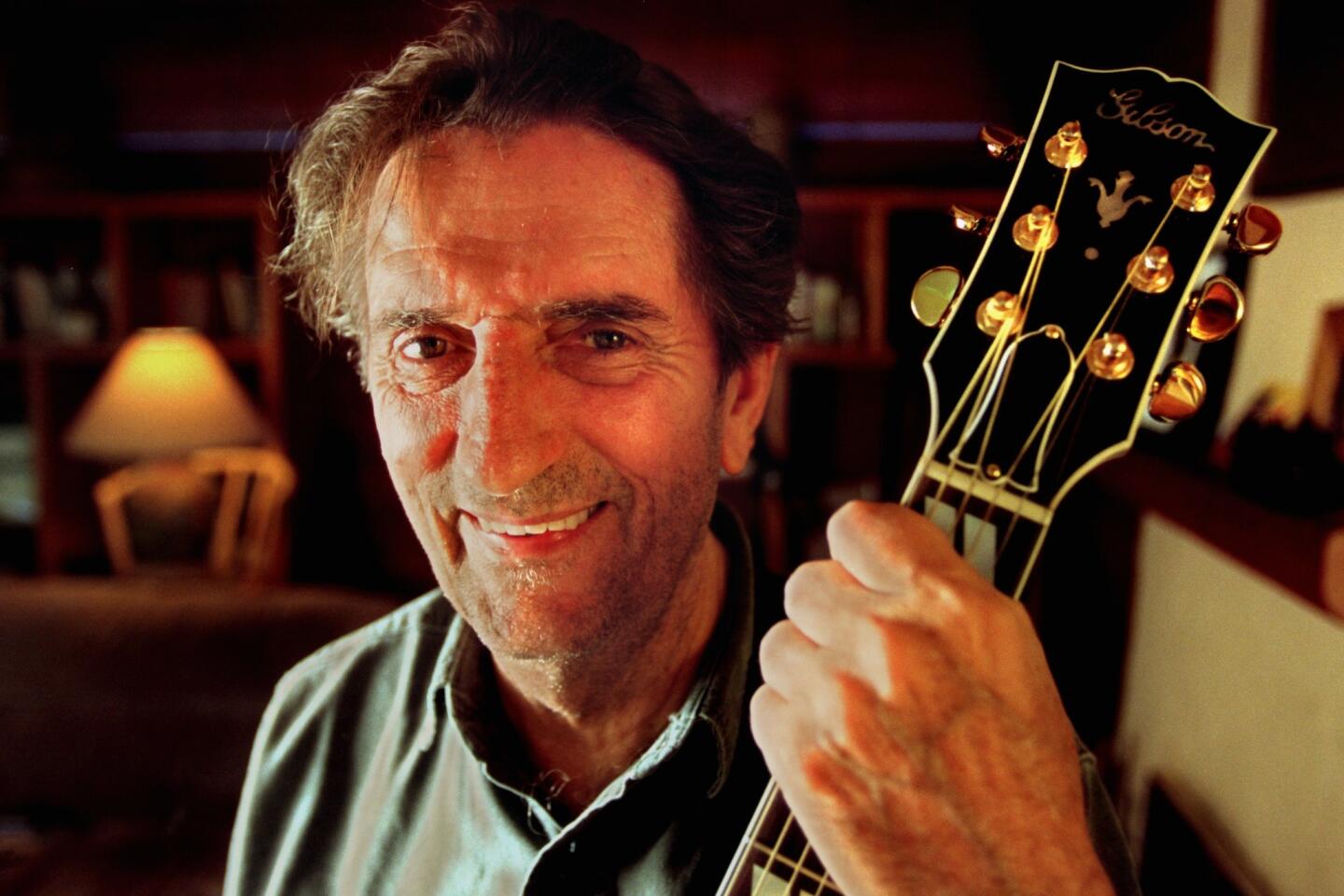

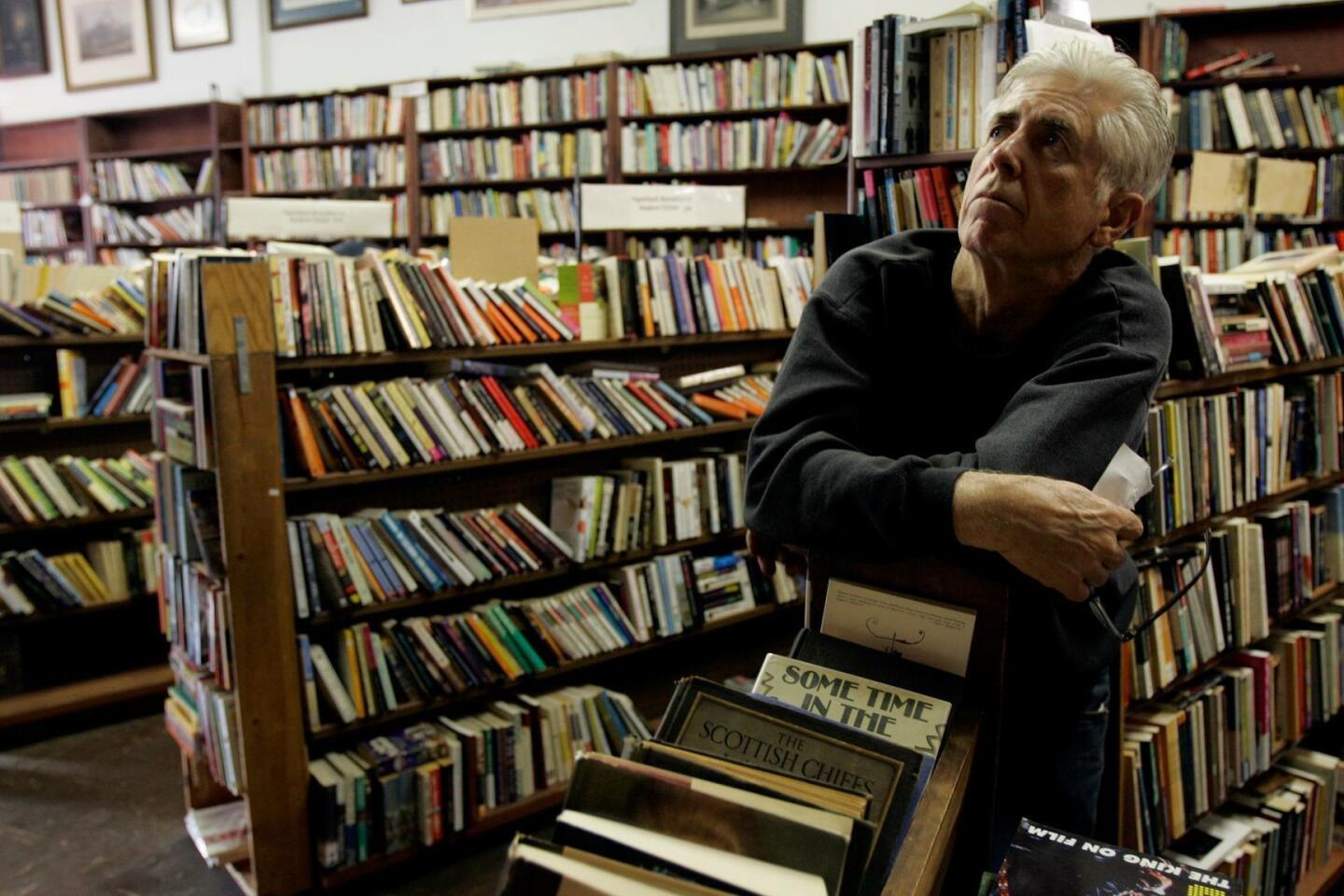

Harry Dean Stanton, character actor in ‘Twin Peaks,’ ‘Big Love’ and ‘Cool Hand Luke,’ dies at 91

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.