Kahlil Joseph and family keep brother Noah Davis’ legacy alive at L.A.’s Underground Museum

- Share via

When artist Noah Davis died late last summer from a rare form of cancer, it was the story of a promising career cut short. Only 32 at the time of his death, the Los Angeles painter, brother of artist and director Kahlil Joseph, had a rising profile: His work had been acquired by important U.S. institutions, and in 2012, he’d launched an alternative arts space, the Underground Museum, which, in its short lifespan, had drawn positive notice from critics and fellow artists.

As part of the Underground project, Davis established a groundbreaking partnership with the Museum of Contemporary Art, which allowed him to curate a series of shows drawn from MOCA’s permanent collection. These would be staged in the Underground Museum’s warren of adjoining storefronts on Washington Boulevard in Arlington Heights, and they would be free to the public — part of the artist’s goal of bringing “museum-quality” works to a working-class neighborhood.

Anyone concerned that Davis’ untimely death might have put an end to this innovative arts program can rest easy. The Underground Museum is thriving — largely because of the efforts of Davis’ family and a new director, Megan Steinman, who have picked up where the founder let off. MOCA chief curator Helen Molesworth, who helped make the partnership happen, also is involved.

In late March, the space unveiled a new exhibition, “Non-Fiction,” a taut gathering of works selected by Davis prior to his death that examine themes of violence against African Americans. In his review, Times critic Christopher Knight described it as a show that “resonates beyond its modest scale.”

Currently, the team is at work on a variety of public programs — dubbed UM Academy — that will include everything from lectures to screenings to art-making sessions. The lineup will be announced in the coming weeks.

“I live and breathe the museum,” says Karon Davis, the artist’s widow — also an artist herself. “Right now, I don’t have time for anything else, except my son.”

In addition to Karon, the rest of Noah’s family also has come together to help administer the space. Joseph, best known for his work with Kendrick Lamar and lately Beyonce, plus his show at MOCA, is involved, as is Joseph’s wife, Onye Anyanwu.

“It has gotten so much support,” Joseph said. “I just feel really blessed — and honored that Noah allowed me to be an integral part of this. And I think a lot of people involved with this project feel like that.”

Steinman says that together, the team has cohered into a group that feels less like a bureaucracy at a nonprofit and more like a group of artists whose goal is to realize the vision of a colleague whose life ended prematurely.

“It’s a very personal space,” she says. “In a way, it’s being around artists and friends.”

Certainly, the group’s ability to maintain Davis’ vision has plenty to do with the artist’s probing and methodical nature.

“Noah was all about the details, the details, the details,” Karon says. “He left us blueprints for about 18 shows and so many notes of what he wanted to happen in the space.”

For the artist, the Underground Museum wasn’t simply a space to show art — it was an artwork itself, a space in which he could bring together seemingly unrelated bits of cultural output and combine them in profound and revealing ways.

The first exhibition in collaboration with MOCA, held last year, featured a series of video works by South African artist William Kentridge, an internationally recognized figure who has shown his stop-motion animation pieces in museums around Europe and the United States. Among the works Davis chose to display was “7 Fragments for George Méliès,” a rumination on the nature of creation — a fitting work for an artist to want to contemplate.

“Non-Fiction,” which is on view until next March, is built around three works from MOCA’s collection: a painting by Henry Taylor, a cut-out work by Kara Walker and a poignant photograph of the widow of a lynching victim by Marion Palfi — all works that touch on the fraught nature of the black experience in the United States.

Noah was all about the details, the details, the details. He left us blueprints for about 18 shows and so many notes of what he wanted to happen in the space.

— Karon Davis, widow of artist Noah Davis

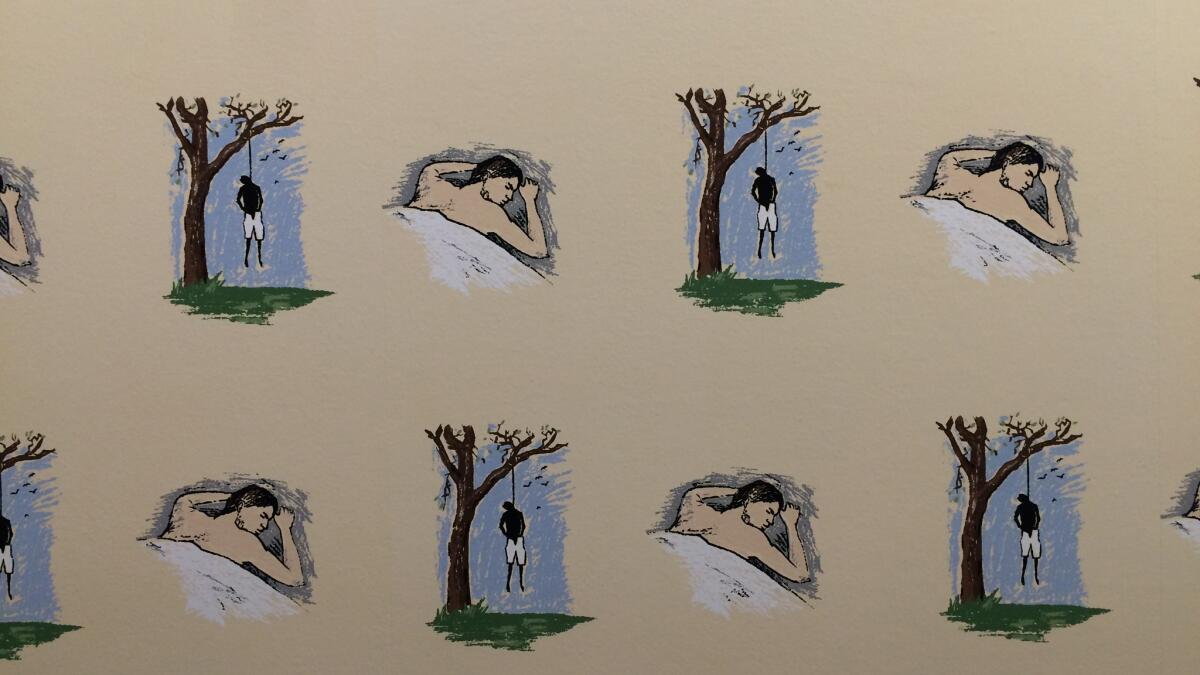

These are paired with other objects that Davis — and the Underground Museum team, in his wake — secured on their own: David Hammons’ ghostly installation of a hooded sweatshirt (evocative of Trayvon Martin’s death in Florida) and Robert Gober’s searing art wallpaper, featuring the image of a lynched black man, alongside a white man sleeping peacefully. The exhibition features only a dozen works, but its punch is powerful.

Together, the museum and the team at the Underground Museum are hashing out which of Davis’ many ideas will serve as the core of the next exhibition, which hasn’t been determined. But the artist had signed on with MOCA for a three-year collaboration, and the museum intends to stand by that.

“The Underground Museum is really interesting because it’s a full collaboration,” says MOCA director Philippe Vergne. “It’s not just MOCA. It’s how can we make possible for someone who has such a great vision, who wants to bring art in the neighborhood, who changes the way a collection is experienced?”

For Davis’ family, who is still mourning his death, fulfilling his plan for the Underground Museum is a way of keeping his presence alive.

“We are all crazy excited about what this means,” Joseph says. “Anyone who is here, it’s like Noah left them something, like Noah created the space for them to be there.”

“I love the work,” says Karon thoughtfully. “And he is in the work.”

For family members, the Underground Museum is something they would like to maintain — even once MOCA is no longer a partner.

“There are so many possibilities,” Karon says. “I would really like this to leave a legacy.”

Where: 3508 W. Washington Blvd., Arlington Heights, Los Angeles

When: Through March 1

Info: theunderground-museum.org and moca.org.

ALSO:

Heinous history as potent muse in Underground Museum’s ‘Non-fiction’

Kendrick Lamar’s video director Kahlil Joseph takes his hypnotic art to MOCA

Wolvesmouth at MOCA: Craig Thornton puts his art on a plate, and then you eat it

‘City of Conversation’ playwright Anthony Giardina on America’s politics of destruction

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.