Q&A: ‘City of Conversation’ playwright Anthony Giardina on America’s politics of destruction

- Share via

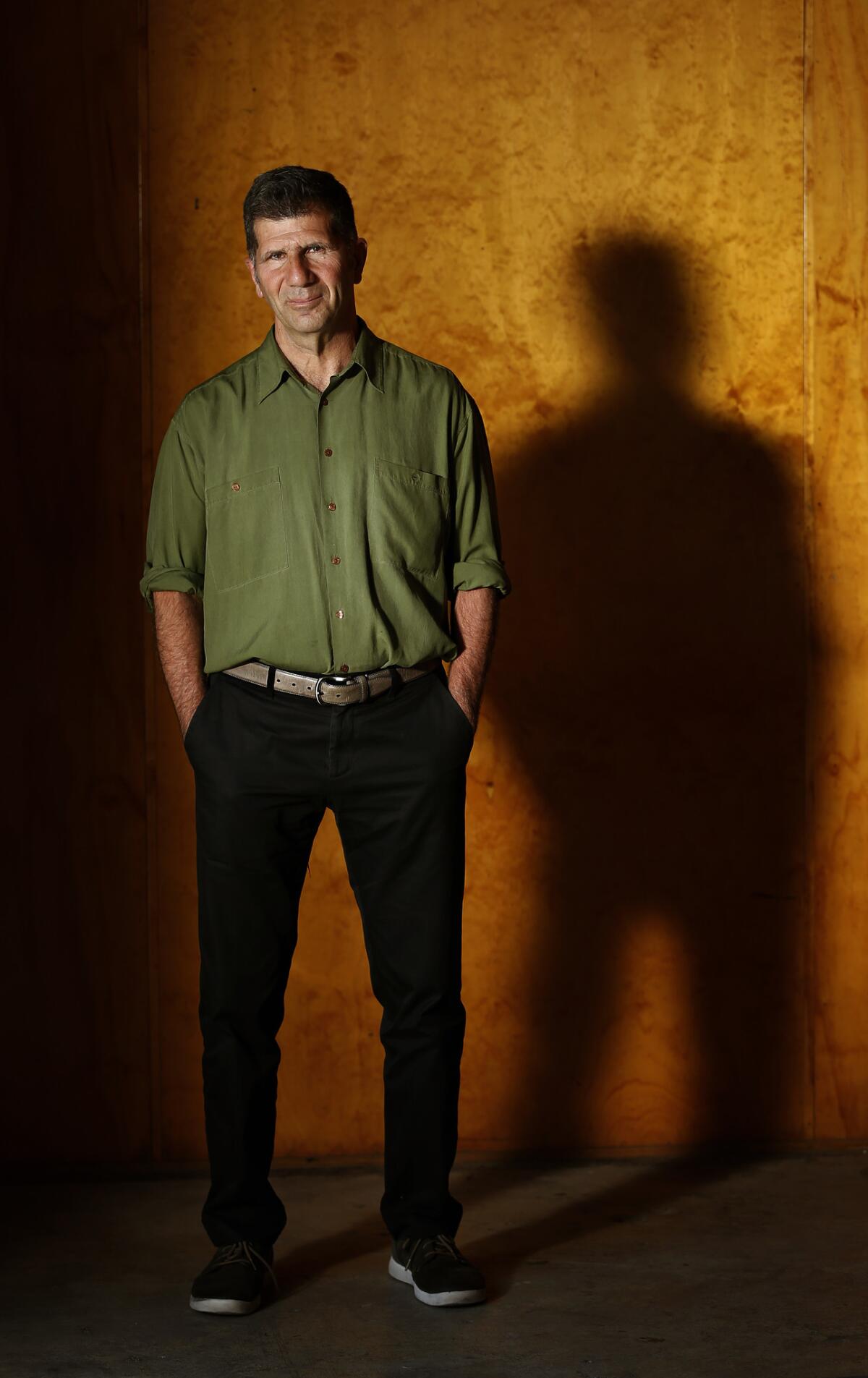

When author and playwright Anthony Giardina sat down to write the stage dramedy “The City of Conversation” in 2010, he had no way of knowing quite how prophetic the play would prove.

The piece is set in Washington, D.C., during three watershed periods in modern American politics: fall 1979, September 1987 and January 2009. In it, Hester Ferris, a Georgetown political hostess, turns political operative to help derail President Reagan's nomination of Judge Robert Bork to the Supreme Court.

The work of Hester (Christine Lahti) and the ripple effects on son Colin (Jason Ritter), daughter-in-law Anna (Georgia King) and, later, adult grandson Ethan (also Ritter), drive the story’s rich narrative.

See the most-read stories in Entertainment this hour >>

As “The City of Conversation” plays through June 4 at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts in Beverly Hills, its foresight into the growing divisiveness of American politics may feel even truer than it did in 2014, when the play first premiered off-Broadway. Giardina spoke to The Times from his home in Northampton, Mass., about how he came to write the play, his political perspective and his deft forecasting skills.

How shocked are you to find that the play, particularly with its focus on a contentious, possibly balance-shifting Supreme Court judge nomination, is so timely?

I don’t find it shocking and I don’t want to give myself too much credit. But because Hester is so much a creature of the 1960s, what people like her consider the golden age under [Presidents] Kennedy and Johnson, I felt there was something potentially very resonant about concentrating again on that moment.

That said, the fact that we’re now in that interesting period where everybody’s talking about Bork because of what’s come up with [President] Obama’s attempt to replace Antonin Scalia on the bench is surprising.

And let me just say, during our recent Washington, D.C., run, there were suddenly lines that I had considered throwaways — like when Colin says, “The president gets to pick his Supreme Court” — that had the audience cheering. That’s just a happy accident.

Where did the idea for the play come from?

Twenty years ago, I read a New Yorker essay by Sidney Blumenthal called “The Ruins of Georgetown.” It was about the world of the dinner party as it existed under [journalist] Joseph Alsop and his wife, Susan Mary Alsop, where people would be invited from both sides of the political aisle. They would be fighting all day about, say, a congressional bill, and at night they would socialize. And, because of that collegiality, you were more likely to achieve a compromise because you knew the person you were fighting against. I was deeply compelled by that.

Why did it take so long to write the play?

It was a world I really had to study and think hard about. So it probably took a dozen years of working on other projects and researching before I was finally able to sit down and write. But I knew I wanted to summon that lost world, which seemed to me so important for us to remember.

Did you always envision the play spanning these three time periods? Did those years change at all during the writing process?

I knew that I wanted to carry the story over time and I wrestled with a lot of potential places to begin. But I thought for a woman like Hester, who came of political age during the Kennedy administration, 1979 would be a perfect place to start. She’s a part of this world that’s been out of power for awhile, and wonders, “Are we going to come back?”

And then there was this whole notion of the Young Republicans, especially the Reaganites, as represented by Anna and Colin. I thought, “OK, that’s interesting. That’s also a good place to begin.” But where do you take Anna and Colin in the second act, what would be their “Waterloo"? Then I thought about the Bork nomination, where everything came to a head.

Finally, I knew I had to take the story into the present — or at least the close present — and nothing seemed more right than the Obama inauguration. I had a sense, by the time this play was produced, that would become a distinct moment in history, which of course it has.

The play’s third scene, set in 2009 and touching upon gay rights, has an almost eerily profound resonance. Did you have to alter the gay marriage content for the play’s 2014 premiere to reflect the sea changes on that front?

Not at all. Again, I don’t want to take too much credit for any great prescience, but when I was writing the play, gay marriage was very much in the air. You could see it as an issue that was going to be the next great Supreme Court battle.

Although the play is largely told from the perspective of Hester, a Democrat, it also makes a clear case for Republican values. What’s your message here for both political parties?

It was very important to me that the Republican point of view be voiced in the most respectful and most intelligent way that I possibly could. Though I’m a Democrat, I’ve always found that when I could hear a Republican argument carefully and intelligently presented, there’s something a little challenging about that — in a very good way for me.

I wanted to give Anna the opportunity to make her arguments. And I’d like the audience to take those in and also to maybe take in how Hester’s partisanship, how a certain kind of partisanship in general, blinds us to nuance. I want an audience to feel that they’ve heard a real conversation in which both sides have been given respect.

Are your characters based on any specific D.C. players?

When I was researching the play I became very interested in people like Katharine Graham [the late publisher of the Washington Post] and Pamela Harriman [the late Democratic fundraiser who became U.S. ambassador to France]. But no, I felt like in order to have the freedom to let Hester’s character range, I had to write someone fully imaginary.

How do you think our 2016 presidential candidates fit into the D.C. zeitgeist explored in the play?

One of the things that’s most important to me, and that the play comes out of, is that we remember history. I hope my love of history is evidenced in this play. I almost want us to take a step back and study every presidency that has preceded the next one, and talk about what happens when a new president comes in. Talk about, for example, what happened when [Franklin D. Roosevelt] came in and how he was able to accomplish what he accomplished.

The most troubling thing for me about this election is the kind of ahistorical mind-set I’m hearing from both sides — this plague of not remembering even what’s happened in recent history.

Follow The Times arts team @culturemonster.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.