- Share via

I wish everyone could be as optimistic as Brian Michael Smith.

I first met the “9-1-1: Lone Star” and “Queen Sugar” actor, who is primarily known for being the first Black transgender man cast as a series regular on network TV, at an event in July that somehow turned into a group therapy session about being Black and queer in the entertainment and media industries.

Smith (no relation, of course) had plenty to say. But what stuck out most were his comments about the often-touted cross-racial, cross-class solidarity of this past “hot labor summer.”

Tens of thousands of livid members of SAG-AFTRA, the actors’ union, had just joined the picket lines alongside equally livid members of the Writers Guild of America, and Smith had been out there a few times.

“I see everybody kind of waking up to the systematic sense of unfairness involved in this; there’s this dual thing happening,” Smith told me later by phone. “People want to fight for who they are as individuals, and they’re fighting for individual freedoms. But then they’re recognizing how we’re all in this together, because capitalism has an impact on all marginalized people — and has the ability to marginalize people.”

He was describing the mood before the WGA and major Hollywood studios reached a tentative deal on a new three-year contract, ending the 148-day strike and laying the groundwork for SAG-AFTRA to do the same.

“There’s a recognition of the diversity that’s within the collective and [a] holding of space for that,” Smith said. “And all of us coming together, recognizing that we do have these differences, that we do have different needs but that we’re all kind of fighting for the same thing.”

This is all true. Hollywood’s striking actors and writers have been united in their objections to the unfettered use of artificial intelligence and demands for a bigger cut of the increasingly paltry residuals payments. The studios largely caved to the WGA on both.

But, as Smith readily acknowledges, Black actors and writers have always had their own “thing” — er, things — when it comes to fighting for fairness.

The underrepresentation. The blatant racism and petty microaggressions. The disproportionately low pay. The “Hunger Games”-like competition for an unnecessarily limited number of roles. The typecasting. The pervasive and ridiculous belief by studios that Black stories don’t sell, unless they are about slavery or “white saviors” — or both.

And so, even as the strikes dragged on for months, upending budgets and stressing households, there’s an important long-term question for Black folks in the entertainment industry: What will come of all this solidarity we’ve seen on the picket lines?

Will it carry over to Hollywood boardrooms, sets and writers rooms once everyone returns to work, providing the necessary momentum to adequately address these longstanding problems? Or will it once again prove to be fleeting, discarded and forgotten like a picket sign?

“It’s really fascinating to see on the picket lines old people walking with young people, Black people walking with white people,” said Jake Lawler, a WGA member who worked on the show “The Crossover” on Disney+. “I worry about where the money will go internally when we come back from this. Where the studios will invest their money, [like] in projects that may not be representative of a complete picture of the United States of America.”

The legacies of the #OscarsSoWhite and #MeToo movements don’t leave much room for optimism. Nor does that of the racial reckoning that followed the murder of George Floyd by Minneapolis police in 2020, leading to a push for equity in all aspects of American life.

A recent analysis from USC’s Annenberg Inclusion Initiative found that, of the 1,600 top-grossing movies from 2007 to 2022, Hollywood didn’t make many strides in terms of on-screen representation for women, people of color, people with disabilities and people who identify as LGBTQ+.

Thirty-one of the top movies in 2022, for example, featured an actor from one of these groups in a leading or co-leading role. That’s up from 13 movies in 2007, but below the recent high of 37 movies in 2021.

It’s not much better for other, more behind-the-scenes roles. In 2020, only 37% of TV writers were people of color, according to a recent WGA West Inclusion & Equity Report.

Hollywood also has pulled back from many of its commitments to diversity, equity and inclusion, canceling shows with diverse casts and forcing out several top-level DEI executives.

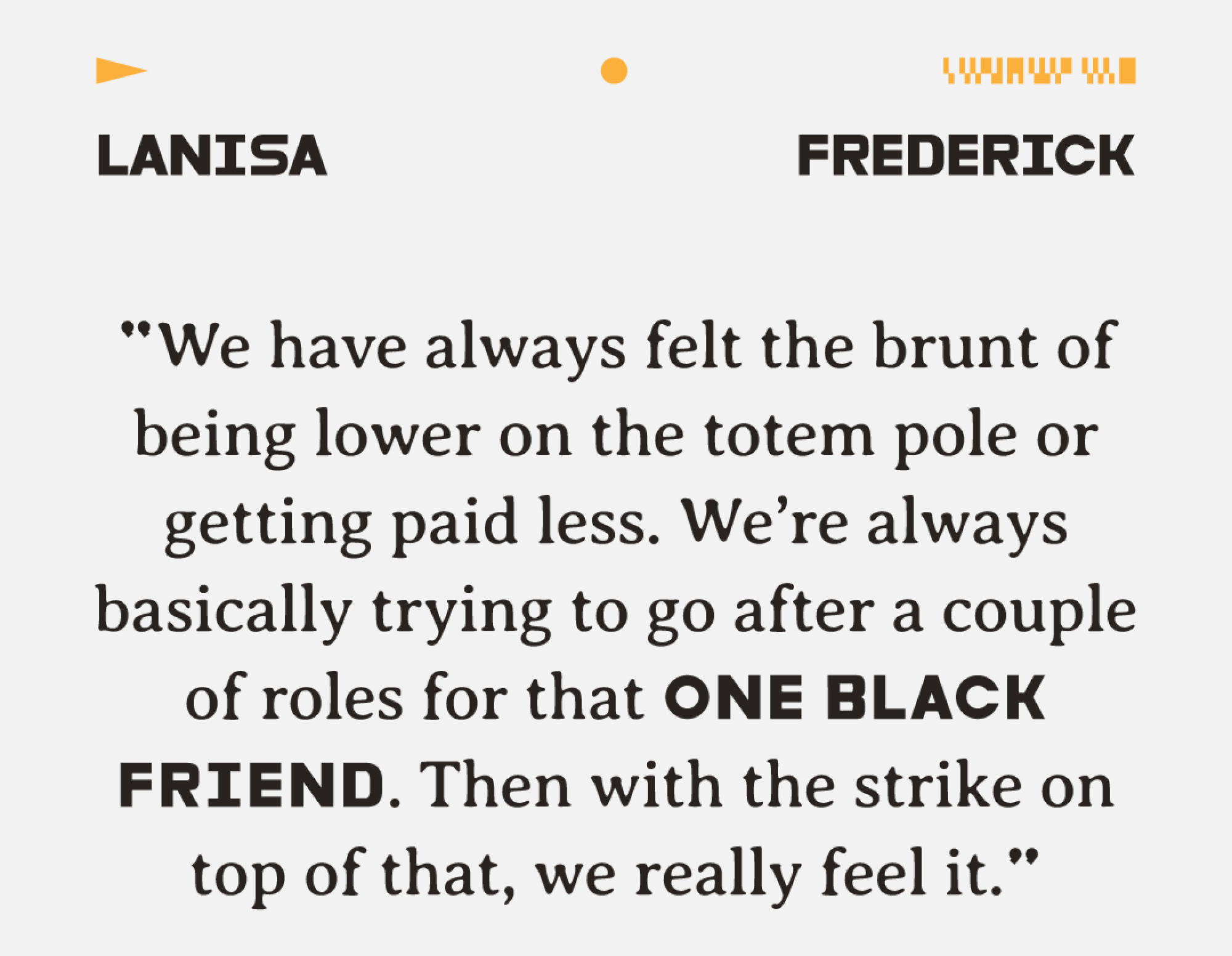

This comes as no surprise to LaNisa Frederick.

Since 2018, she and fellow actor Danielle Pinnock have been making similar observations — along with all the other nonsense that comes with being Black actors — through their Instagram comedy series, “Hashtag Booked.”

In fact, I could see Frederick, a regular on the new Fox series “Snake Oil,” bristling over Zoom as she thought about all the empty promises that were made during the racial reckoning of 2020.

“There was a major producer that came to us during that time,” she said. “We had been doing this thing online for a minute and they were like, ‘You know what? Black people matter. Your representation matters. You Black women need a show.’ This happened to a lot of Black creatives during that time. They just wasted our time for years.”

Pinnock scowled and growled as Frederick spoke.

“It just grinds me that when the industry said that representation mattered, I don’t think they truly meant that,” said Pinnock, who plays Alberta in the CBS sitcom “Ghosts.” “They really just wanted to fill a quota. Like an ornament on the Christmas tree, we were just nice to look at.”

The Asian girl. The Latino teenager. The transgender Black man, just to check multiple boxes at once.

“They didn’t care about who we were, our stories, what makes us tick,” Pinnock added. “There was no specificity in this representation at all. And also, even behind the scenes, there was still nobody there to do our hair. There was still nobody there that could actually do our makeup. We’re still going out on set looking like Casper.”

Indeed, this is one union demand that has gotten less attention but wholly speaks to the Black experience in Hollywood.

The Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers, which represents the studios in the negotiations, has been called on to give all actors of color access to professionals who understand how to style their hair textures and apply makeup appropriate for their skin tones. But according to SAG-AFTRA, the studios have agreed to do so only for principal performers, not for background actors.

“Why am I being written for by some white guy that’s from Omaha?” Pinnock asked incredulously when we spoke in August. “Why are there not more Black writers in this room? Why are there not more people behind the scenes? Directors? Editors? Why is that missing?”

Lawler was among the Black writers who rode the racial reckoning wave to a job in Hollywood. After making a name for himself as a college football player, he decided to pursue a career in entertainment, using Google and YouTube to teach himself how to write a TV pilot.

He ended up working in an all-Black writers room — something he knew wasn’t typical and probably wouldn’t last. He called the push for diversity, inclusion and equity a “thin veil” of a movement — and I’d have to agree.

“Like any world in which Hollywood needs to cut costs, I think people that look like you and me are going to be first on the chopping block,” Lawler said. “So I do think that there’s going to be a contraction in terms of what is being bought, what is being greenlit, what is being financed.”

In the meantime, the strikes have taken a toll on everyone — except the wealthy few. But as the old saying goes, when white people get a cold, Black people get the flu.

“We have always felt the brunt of being lower on the totem pole or getting paid less,” Frederick said. “We’re always basically trying to go after a couple of roles for that one Black friend. Then with the strike on top of that, we really feel it.”

Many of the terrible socioeconomic statistics that have long defined Black life in America have collided with the strikes. The wage gap, particularly for Black women. The low homeownership rates in a city with astronomical housing costs. The lack of generational wealth and high rates of poverty. The difficulties of securing loans and other lines of credit.

And what’s worse is it’s unlikely that the studios’ contract with the WGA, and eventually with SAG-AFTRA, will address other pertinent problems. The trauma of hearing racial slurs at work, for example, or having the validity of one’s very existence continually dismissed.

“I have called Danielle and said, ‘Yeah, they used the N-word on set today again,’ ” Frederick said.

Because, of course, that is still happening.

“That stuff is not on the list,” Pinnock added, unlike artificial intelligence and residuals.

Hollywood is in the business of telling stories. Of making us believe in the fantastical. That good can triumph over evil, that the underdog can win, that money isn’t everything and that life can be fair.

But in the real world, maybe these are the limits of solidarity.

“Yes, we are all artists. We are all performers. But our issues are also very granular,” Pinnock said. “I don’t know if they’re all going to be hit during this strike. I’m terrified that they won’t.”

Much like Smith, though, Lawler is taking solace in the unity that has come out of this labor movement.

“It’s an unfortunate situation,” he said, “but maybe the fortunate outcome is trauma bonding. A bunch of people at different levels of the industry, like across race and class and color boundaries, are walking together, side by side, because we’re all getting treated unfairly by our employers.”

His hope is that connections are made and relationships are formed.

Maybe once the members of SAG-AFTRA can follow members of the WGA and return to work, a white producer will think of the young Black actor he met on the picket line. Or maybe a showrunner will remember the conversation he had with a Latina writer.

Maybe now the relationships of Hollywood will be less insular.

Maybe.

“I would be hiring people that I met on the picket line,” Lawler said. “And I can say with an almost near certainty that I’m not the only person that feels that way.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.