Opinion: I helped write the surprise Netflix sensation ‘Suits.’ My reward? $259.71

- Share via

In America, unprecedented success begets unprecedented wealth. When Michael Jordan wins six championships or Mark Zuckerberg invents social media, they earn billions.

And not only them but also their teammates — the people whose contributions weren’t just meaningful but necessary. In success, they get paid, too.

But not in Hollywood. Here, when you write for a show that becomes an unprecedented success, there is no such windfall. There is only a check for $259.71.

It doesn’t matter whether the show you helped build generates 3.1 billion viewing minutes in one week across Netflix and NBCUniversal’s Peacock, setting a Nielsen record. It doesn’t matter whether said show constitutes 40% of Netflix’s Top 10.

$259.71: That’s how much the “Suits” episode I wrote, “Identity Crisis,” earned last quarter in streaming residuals. All together, NBCUniversal paid the six original “Suits” writers less than $3,000 last quarter to stream our 11 Season 1 episodes on two platforms.

Yes, it’s gratifying that the show has found a new and bigger audience this summer on Netflix. Every writer and actor hopes their work will endure. And yes, I’m grateful to have been in the engine room of “Suits” for eight of its nine seasons.

But $259.71 for writing a show with an audience so massive? This is why writers and actors are on strike. This is why SAG-AFTRA President Fran Drescher has used terms such as “un-American” to describe this system.

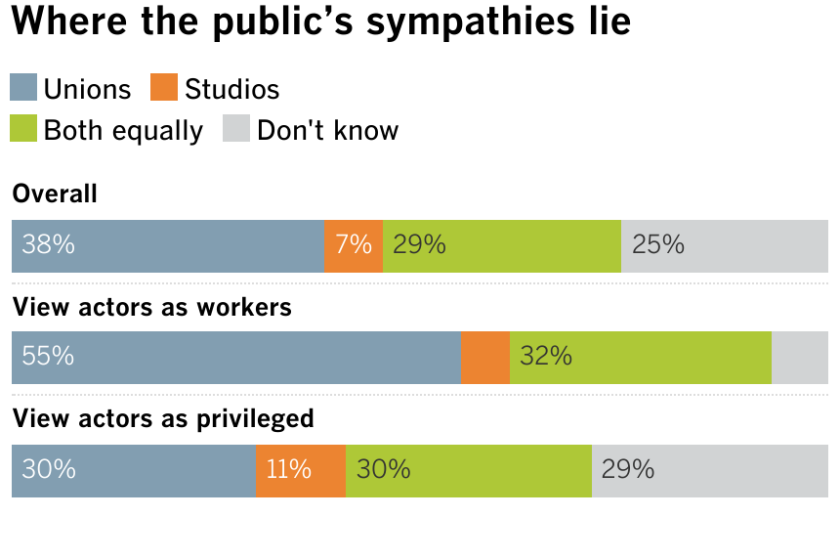

A new L.A. Times poll on Hollywood’s double strike finds the public is more likely to support striking actors and writers than studios and streaming services. But many express ambivalence.

Entertainment executives argue that they are offering writers historic raises. The thing is, even a 100% increase on a $259.71 check doesn’t come close to paying most people’s rent.

Even in a best-case scenario — which “Suits” most definitely is — streaming simply offers no upside for writers and actors and no correlation between results and compensation.

Being underpaid is only part of the problem. The other part? Not being paid at all.

“Suits” became so popular globally that it was licensed and remade in South Korea, Japan and Egypt. When that happens, studios are supposed to pay the writers for the source material.

But a couple of quarters after the Egyptian version of “Suits” began airing last year, I asked the Writers Guild of America to look into why I hadn’t been paid. So far, the guild’s small but intrepid enforcement team has been stonewalled.

The streaming success of “Suits” may be rare, but my experience is common. My fellow writers and actors have taken to posting their own paltry residual checks on social media. Others are owed money for work completed years ago.

A lack of equitable compensation is a valid enough reason to strike and one that most Americans can relate to. Writers and actors are merely the latest arrivals in this late-stage capitalist purgatory.

Workers in film and TV, most of whom are pro-union, have been trying to make ends meet amid a dual strike of Hollywood actors and writers.

But this fight is about much more than what writing an episode of “Suits” is worth. It’s about how entertainment is made and paid for more broadly.

Whether you’re an airport baggage handler or a schoolteacher or a television writer, you rely on a whole team to get the job done well. Aaron Korsh, the creator of “Suits,” worked for two years to craft a compelling pilot and made all the big decisions that guided everything we did. But a mock trial episode that truly elevated the series came from Erica Lipez, the sixth writer hired.

Without Lipez’s contributions, there would still be a show. Without any three of us, there would still be a show. But it wouldn’t be “Suits.”

You can’t subtract Sean Jablonski’s subversive edge, Jon Cowan’s storytelling know-how or Rick Muirragui’s laugh-out-loud dialogue and have a Season 1 that lays the foundation for another eight.

In recent years, streamers have exerted downward pressure on the number of writer-producers who work on shows and stripping early- and mid-career writers out of the casting, production and editing processes. On “Suits,” writers participated in every step of their episodes, which contributed to the show’s quality. That rarely happens now.

An overlooked aspect of this strike is that writers and actors are fighting to protect the quality of the shows that people watch.

The resurgence of “Suits” comes at an opportune moment for executives. The business is shut down; they have time to take stock of what has worked and what hasn’t. Among the questions they might ask:

What does it say that a show that debuted 12 years ago is outperforming dozens of newer original series that Netflix has spent hundreds of millions of dollars producing?

What is the real value of the limited series that streamers have been cranking out? Are viewers as likely to revisit short-lived, ripped-from-the-headlines one-offs about corporate scandals or small-town murders as they are a fully developed, long-running drama?

Are viewers craving more carnage and darkness or cable news sermonizing? Or are they hungry for shows that leave them feeling good?

Only the streamers can determine what kind of content they produce and distribute. Writers and actors are powerless to negotiate that.

But many artists are certain that what is broken about Hollywood isn’t just compensation. It’s what’s being made and why.

Unlike many shows today, “Suits” wasn’t made out of fear. Alex Sepiol, the executive most responsible for championing the series, bet that viewers would respond to a show with an unknown creator and mostly unknown cast because the material was simply that funny and human. More than a decade later, that bet is still paying off.

If only it were paying off for the actors and writers who helped make it a winner.

Ethan Drogin is a television writer and producer.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.