Taylor Lorenz knows social media. So why is her book a dull celebration of marketing deals?

- Share via

Review

Extremely Online: The Untold Story of Fame, Influence, and Power on the Internet

By Taylor Lorenz

Simon & Schuster: 384 pages, $30

If you buy books linked on our site, The Times may earn a commission from Bookshop.org, whose fees support independent bookstores.

According to Taylor Lorenz, social media platforms have turned the internet, once a colorless hellscape of bad graphics and words clumped into ungainly shapes called paragraphs, into a wonderland of cute memes and hilarious videos generated by young go-getters whose creativity has been unleashed by idealistic outfits such as Facebook, YouTube and TikTok. These platforms are saving humanity from “legacy media,” a malevolent cabal of paragraph-peddlers Lorenz has managed to infiltrate with undercover stints as a technology reporter for the Atlantic, New York Times and Washington Post.

If that strikes you as about right, then you are the perfect audience for Lorenz’s new book “Extremely Online,” a purported “social history of social media.” You may even be one of the influencers stuffed into this glorified press release, squeezed somewhere between vlogger Bree Avery, former MTV executive Fred Seibert and Tardar Sauce, a.k.a Grumpy Cat, “a female blue-eyed mixed-breed cat with a distinct frowning expression.”

A lawsuit against “kidfluencer” Piper Rockelle offers an unsettling glimpse into a largely unregulated world of social media content creation, a Times investigation found.

But if you happen to have followed the stories on child predators on Instagram, young men radicalized on YouTube, young women driven to suicide by TikTok or the unabashed racists and antisemites running rampant on Twitter (sorry, not calling it “X”), you will marvel, as I did, that a journalist whose beat is the internet — Lorenz lives in Los Angeles and currently writes for the Post — could insist on such a strangely sunny take of the digital existence.

To place “Extremely Online” against Siddharth Kara’s “Cobalt Red,” an investigation into the horrific exploitation of Congolese laborers who mine the minerals that power our devices, is to indict the whole of our extremely online culture.

Another instructive comparison is to Barrett Swanson’s visit to Clubhouse, one of the influencer mansions that came to dot the Westside during the pandemic years. His article in Harper’s has something of Joan Didion’s wry bemusement about the vacuity of modern celebrity. Here is Lorenz on the same phenomenon: “The ecommerce platform Wish and the social media app Clash both rented sprawling mansions where creators could produce exclusive content. Other brands did pop-up collab houses around L.A.”

In recent years, Lorenz has emerged as the right’s bête noire for reasons I cannot claim to fully understand. Some of it may have to do with her recent unmasking of the woman behind Libs of TikTok, a dishonest clearinghouse of conservative cultural outrage. But the animus preceded that article. The obsession with her private life, social media posts and petty but unremarkable professional beefs says far more about the cultural right than it does about Lorenz. A book about her experiences in the eye of the Daily Caller storm would have made for infinitely more interesting reading than the chronicle of how surfing influencer Baxter Box got a deal with Billabong.

At the New York Times, where she first gained widespread attention, Lorenz skillfully penetrated burgeoning online communities and explained their strange rites to people who wouldn’t know Tardar Sauce from Garfield. Revisiting some of her pre-pandemic work, I encountered a talented and ambitious journalist. There were few of the omissions and misjudgments, little of the clumsiness and misdirection, that plague “Extremely Online.”

A journalist in California was at the center of a lot of drama on social media last week.

I hope that doesn’t sound condescending; it isn’t meant to be. My point is that if Lorenz truly believes that social media platforms have been a democratizing force, she is more than capable of producing something more substantial than a fever dream of proper nouns: Pokimane, Mr. Cashier, Jenna Marbles, the Chernin Group, GrapeStory.

Who are these people? I still have no clue. Nearly every character in the book, with a few exceptions, is described as the sum of marketing deals and social media followers. “Extremely Online” is crammed with people but devoid of life, especially as the social media revolution accelerates and influencers spring up like mushrooms after spring rains.

The book made me appreciate how rare it is to encounter good writing about the internet. It does exist, though. If you want to learn how Tumblr continues to shape internet discourse, read Kaitlyn Tiffany’s seminal Atlantic essay “How the Snowflakes Won.” To better understand how algorithms have infected our inner lives, fling aside this review and turn to Amanda Hess’ “This Is Your Brain on Peloton,” a superb profile of exercise influencer Cody Rigsby. Without needlessly mocking her earnest subject, Hess devastatingly deconstructs the culture of online fandom through the lens of an overpriced stationary bike’s LED display. I can’t wait for her book.

For that matter, Ben Smith comes much closer than Lorenz to a social history of the internet in his recent book “Traffic.” But there is still a definitive, “Liar’s Poker”-style chronicle to be written about the Allbirds-clad elite of Palo Alto. As much as “Extremely Online” wants to be that book, it ends up reading like a marketing report, produced for Santa Monica execs who get their rocks off on fictional valuations, porn for people who’d rather “like” than love.

Lorenz believes that the advent of blogging “demolished traditional barriers and empowered millions who were previously marginalized.” Her heroes are the “influencers” and “creators” who are sometimes able to make millions by hawking sponsored content, or spon-con, in short videos intended to go viral.

Worsening economic conditions could be a stress test for the burgeoning influencer economy. But online creators are pivoting by telling viewers what not to buy.

A watershed moment comes in 2006, when Google buys YouTube. “Google was taking a big bet, but when it looked at YouTube’s rise, it saw pure potential,” writes Lorenz, putting every cliché in the English language through a Peloton workout. We learn in the next paragraph that “none recognized its promise as clearly as Google Video’s partnerships manager, George Strompolos.”

I don’t know about you, but the arrival of a “partnerships manager” on the scene always roils my animal spirits. Ten bucks says you’ll never guess how Strompolos felt after Google chief executive Eric Schmidt “asked Strompolos and several of his colleagues to join the YouTube team.” According to Lorenz, “Strompolos was thrilled.”

The conspicuous lack of original insight made me think Lorenz wasn’t especially thrilled by her own premise: “Blogs offered readers everything that legacy media couldn’t, revealing what writers really thought.” Yeah, no, not really. I’m pretty sure the newspapers and magazines she has worked for still publish op-eds and essays in which writers reveal what they’re thinking. Some of them even blog.

The writing here is joyless and rushed, like a hangover doom-scroll. A new platform is invented, algorithms are gamed, fortunes are made, and then the next platform comes along. The union of corporations and “creators” is treated with the import of Allied armies meeting on the Elbe River in 1945: “One campaign, for computer giant HP, featured Viners Jessi Smiles, Brodie Smith, Robby Ayala, and Zach King sharing an HP notebook/tablet.” My reaction to such developments summarizes my prevailing feeling about this book: Who cares?

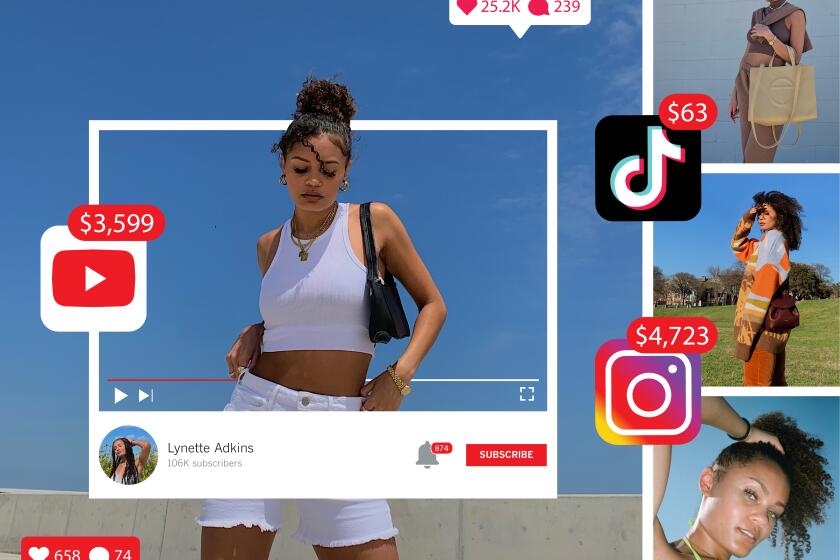

Meet Lynette Adkins. She’s part of a new crop of creators focusing their content on the how-to of the business: making money from an online following.

The goal, always, is to get rich and famous by making people click on things and buy stuff. Depressingly, Lorenz seems to believe that recording videos that hawk clothes made in an Indonesian sweatshop fulfills some kind of liberatory ideal.

That there is something profoundly disturbing about turning a generation into the technostate’s willing influencers never seems to disturb Lorenz. More than once, she struck me as less an internet explorer than a digital prisoner, making “Extremely Online” a kind of Stockholm syndrome manifesto.

The pandemic drove us all online; some of us have stayed there, whether out of necessity or desire. Advances in artificial intelligence will soon make digital reality even more enticing, while degrading our experience of the real world. Still, one wants to believe that there is more to heaven and earth than what is known by Tardar Sauce.

Nazaryan writes about culture and politics.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.