How do influencers make money? And how much? She’ll tell you

- Share via

Last summer, Lynette Adkins was a fresh college graduate starting a corporate career at Amazon that she thought would be her ticket to financial freedom — the kind that seemed out of reach growing up in her middle-class family.

She lasted only a year.

Today, 23-year-old Adkins earns double as a self-taught content creator what she made at Amazon Web Services marketing cloud products. In a crowded influencer market, she’s carving out a niche by turning the camera on herself in a way few others have: detailing how, exactly, to make good money and a sustainable career from having an online following.

“I never see this kind of information about what people are making … what the true possibilities are as far as profits go when it comes to creating content,” Adkins said in a video posted in July on YouTube, her main moneymaking platform.

In June, when Adkins saw that she made more from her YouTube videos and brand sponsorships than from her 9-to-5 job, she quit Amazon — and documented the whole process for all to see.

“I’m scared to not be making as much money as I’m making from this job,” a crying Adkins said in the video, “i quit my job (and filmed everything).” Her next YouTube post became the first of her now-signature budgeting videos — and maybe the moment her college side hustle turned into her new career.

In it, Adkins breaks down her earnings, down to the dollar, to explain why the Amazon job had lost its luster. Of her $14,023 in June income, just $5,300 came from the e-commerce giant. She earned the rest through YouTube, Instagram and other online work.

The written word is making a comeback in an unlikely place: TikTok. The reasons for that include accessibility concerns and changes in the way Americans consume media.

Gone are the days of the accidental YouTube celebrity — a teenager whose homespun video spontaneously goes viral, landing her a moment in the spotlight. Many influencers set out strategically to make a living from sharing their lives or skills online. Content creators are the fastest-growing type of small business in the U.S.

Gone, too — for the most part — is the misconception that this digital work is the exclusive domain of spoiled or lazy well-to-dos.

“I’m currently trying to unlearn a lot of things that I grew up learning around work and money,” said Adkins, who grew up in San Antonio and started working at age 15 to ease the financial load on her father, a real estate agent, and her mother, who works for an insurance company.

Adkins’ content also speaks to the themes of discontent that run through Gen-Z-produced social media. Two of her videos denouncing corporate culture went viral earlier this year, one titled “I became the main character and it changed my life,” and the other, “I don’t have a dream job.”

Adkins encourages viewers to detach their self-worth from their jobs. “These corporations will try to make you feel like at home in your work or at your job,” she said in a later interview. “It’s just a source of income. For me, that’s all it will ever be.”

Her message hit home for her viewers. In four months, she gained 70,000 YouTube subscribers.

‘Point of view’

After connecting with viewers over their unfulfilling white-collar jobs, Adkins offers them a way out. Her budgeting videos, a road map of sorts to becoming an influencer, quickly galvanized a fast-growing audience.

“There’s never been a better time, I don’t think, to be in the content creation business because the demand is still exploding,” said Robert Kozinets, a professor who studies digital interaction at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism.

The influencer marketing industry will command about $12 billion this year in the U.S. and closer to $30 billion globally, according to research by Kozinets.

In a departure, creators partaking in YouTube’s new $100-million fund will be paid based on viewership and engagement rather than advertising revenue.

On LinkedIn, the share of job postings for roles with the words ‘influencer’ or ‘brand partnerships’ through July of this year grew 52% from the same period last year, according to an analysis done by the company for The Times.

On YouTube, the number of U.S. creator channels making at least six figures in revenue was up more than 35% year over year as of December 2020, according to the company.

YouTube’s Partner Program, which pays a set amount of ad revenue per every thousand views a video gets, has shelled out more than $30 billion to creators, artists, and media companies.

“The easier part is the monetizing, believe it or not,” said Seth Jacobs, a talent manager at Brillstein Entertainment Partners. “The hard part is finding people with a point of view.”

Adkins’ supporters say they are wowed specifically by the amount of personal information she shares.

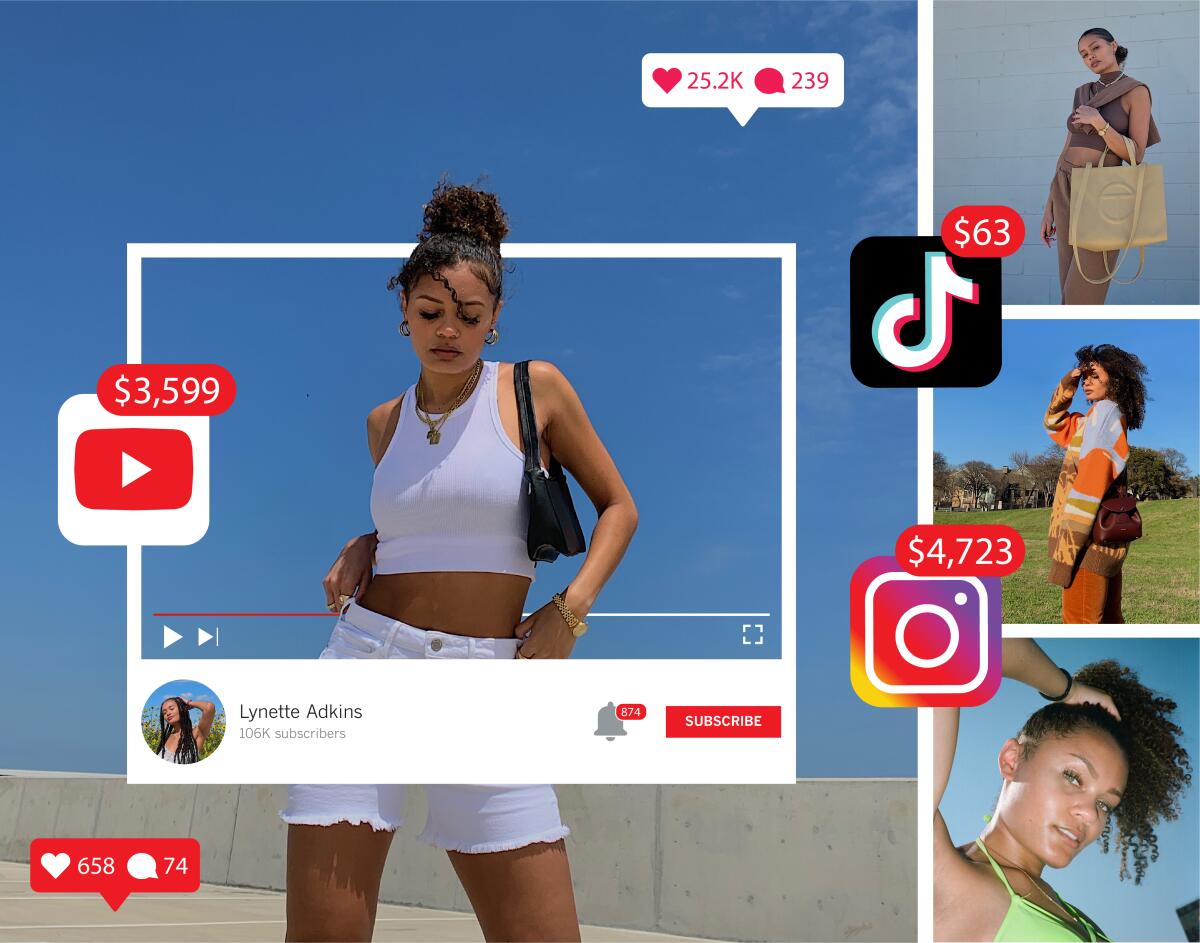

In her June earnings video, she explains that of her $14,023 take-home pay that month, $8,723 came from her creator work: about $4,700 from sponsorships, $3,599 from YouTube ad revenue, $263 from affiliate marketing and $63 from TikTok.

“I just want to say, you inspire me and we need people like you, with a voice of their own, and content about the things people don’t talk about or don’t talk about enough,” read one comment on the video, among some 500.

Another: “I absolutely LOVE the transparency! So many people hold this information as a ‘secret’ but this inspires and helps me so much since I have similar aspirations and learn best by being walked through it.”

You’ve seen TikTok, Instagram and YouTube launch people into Hollywood stardom. Here are some tips for getting started as a social media influencer or creator.

Others are drawn to her nuanced conversations around work and self-worth.

Katherine Berry, one of several creators who made a video inspired by Adkins, called the videos “kind of radical, because you don’t see many young professionals talking about this” — how work shouldn’t consume one’s life.

In addition to making YouTube videos, Berry works in tech sales, a job she said involved 12-hour days until she recently set firmer boundaries around work hours.

Adkins’ content also stands out because the creator economy remains relatively opaque in its inner workings, even to creators. Brand deals are subjective, and it can be difficult for newbies to navigate their early days making money online.

“It’s basically like a black box” said Lindsey Lee Lugrin, the chief executive of FYPM, a company whose platform enables creators to reveal their earnings from sponsored posts and review companies they’ve worked with.

Deconstructing the how-to of influencing has been increasingly trending online, but it remains “a stigmatized/taboo topic (especially for women),” Lugrin, who hasn’t seen Adkins’ content, said in a later email. “So anyone who uses their influence to uplift other creators and help them negotiate higher rates is a hero in my book.”

Adkins traces her money savvy back to her teen years, when, watching her parents struggle through the 2008 recession, she started working to support herself.

Many classmates came from wealthier families — they got tickets to the movies and trips to the mall. “Keeping up with that meant I had to work,” she said.

When she was in high school, Adkins started watching YouTube videos regularly, mostly by beauty personalities who taught makeup tutorials. But the beauty space, especially, seemed reserved for young, white women.

A few years later, around 2016, she began to notice a shift on YouTube. Instead of videos covering one specific topic, more “lifestyle content” was populating her feed.

Creators started to show more of their everyday lives online: One might post a smokey-eye tutorial, a video about how she decorated her living room, and what she ate that week. Now, a person’s multifaceted personality could, and should, be reflected in their content.

This seemed more up her alley.

Many Black TikTok creators say the platform exploits their content while suppressing their voices. For some, the only solution is to pick up and move to other platforms.

In January 2018, Adkins made her first video: a tutorial for Black women growing out their natural hair. She mostly saw YouTube as a creative outlet while finishing her business major and as another source of income alongside other jobs.

She got her real estate license to rent apartments to fellow students and worked as a valet and at a call center.

That year, Adkins filmed videos on college life, skin and hair care, and studying abroad. She would film herself with her iPhone, often propped up in a windowsill. Later, her boyfriend would shoot photos of her for her Instagram account.

‘I don’t dream of labor’

Out of college, Adkins accepted the well-paid role at Amazon Web Services in Austin, which she scored through a networking event for Black college students. She said she didn’t enjoy the job, but needed it, and started to doubt the corporate path just a few months in.

Adkins said her questions about “hustle culture” began in the classroom. In her business courses, she felt like she was training to be an employee, not an entrepreneur.

She started reading Eckhart Tolle. She learned more about Black history and America’s systemic inequities.

“The reason there’s so much inequality in this country is not because there’s not enough resources,” she said. “It’s because there are enough resources, but people at the top, like the 1%, have kept a majority of the world’s resources for themselves. And that’s why I started realizing that we can have it all, but there has to be change.”

The killing of George Floyd added a layer of ethical questions to her work — she helped sell AWS’ cloud computing platforms to government agencies, including police departments. “That was a moment when I was really asking myself, what am I actually doing?” she said.

She channeled the angst and uncertainty into her YouTube channel, deciding to focus on growing a following until it was financially viable to leave her day job behind.

Pent-up demand, pandemic savings, back-to-office mandates -- experts say it will all add up to a historic wave of people leaving their jobs.

She bought herself a tripod, filming wherever she could, which was often in her parking garage. She made her first big camera purchase in March of this year, a $750 Sony ZV-1, marketed specifically to vloggers.

That month, her two videos on rejecting the live-to-work culture blew up. Adkins now has more than 105,000 YouTube subscribers, 22,000 Instagram followers and 101,000 followers on TikTok — making her a so-called micro-influencer on the ascent, someone with a sizable and engaged following but who isn’t a big brand personality or household name.

These days, Adkins is focusing her content less on fashion and beauty and more on spirituality and manifestation, taking control of your life and acknowledging the inequities of capitalism.

The latter popularized a viral tagline, “I don’t dream of labor,” which dozens of other creators have used in similar videos with their own stories of leaving, or changing their outlook on, competitive jobs. The origins of the movement may be traced back to a Twitter post by a writer, though the use of the phrase surged on YouTube after Adkins’ video. (Adkins doesn’t claim to have coined it.)

In months that she publishes more videos, she notices that her channel gets more attention all around (Adkins said algorithms reward frequent posting). If she’s running low on sponsorships one month, she’ll make more videos for more ad revenue, or seek out more brand deals, the next month.

“I know how I can control each source of income and, like, increase one or the other,” she said.

The paradoxes of Adkins’ story aren’t lost on her. What enabled her to quit her corporate job was talking about her disdain for it online. And with her new career, she’ll quickly admit that she’s still fighting capitalism with capitalism.

Yet she said she feels she has more control over what she puts into the world, and she feels good about that. “I freed myself,” she said, “but there’s so much more that I want to do.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.