- Share via

Lucio Rodarte’s death was not a mystery.

Two days after his body was found in an alley in Compton in 2009 — hands cuffed behind his back, bandannas tied around his eyes and stuffed in his mouth, shot twice in the head — an informant went to the FBI. The source said he’d seen a member of the Mexican Mafia threaten and extort from Rodarte inside a tattoo parlor just before he was killed, according to an FBI report.

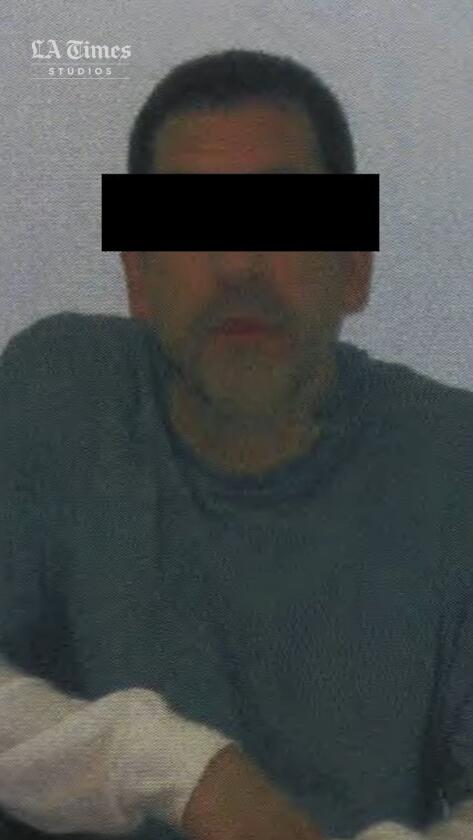

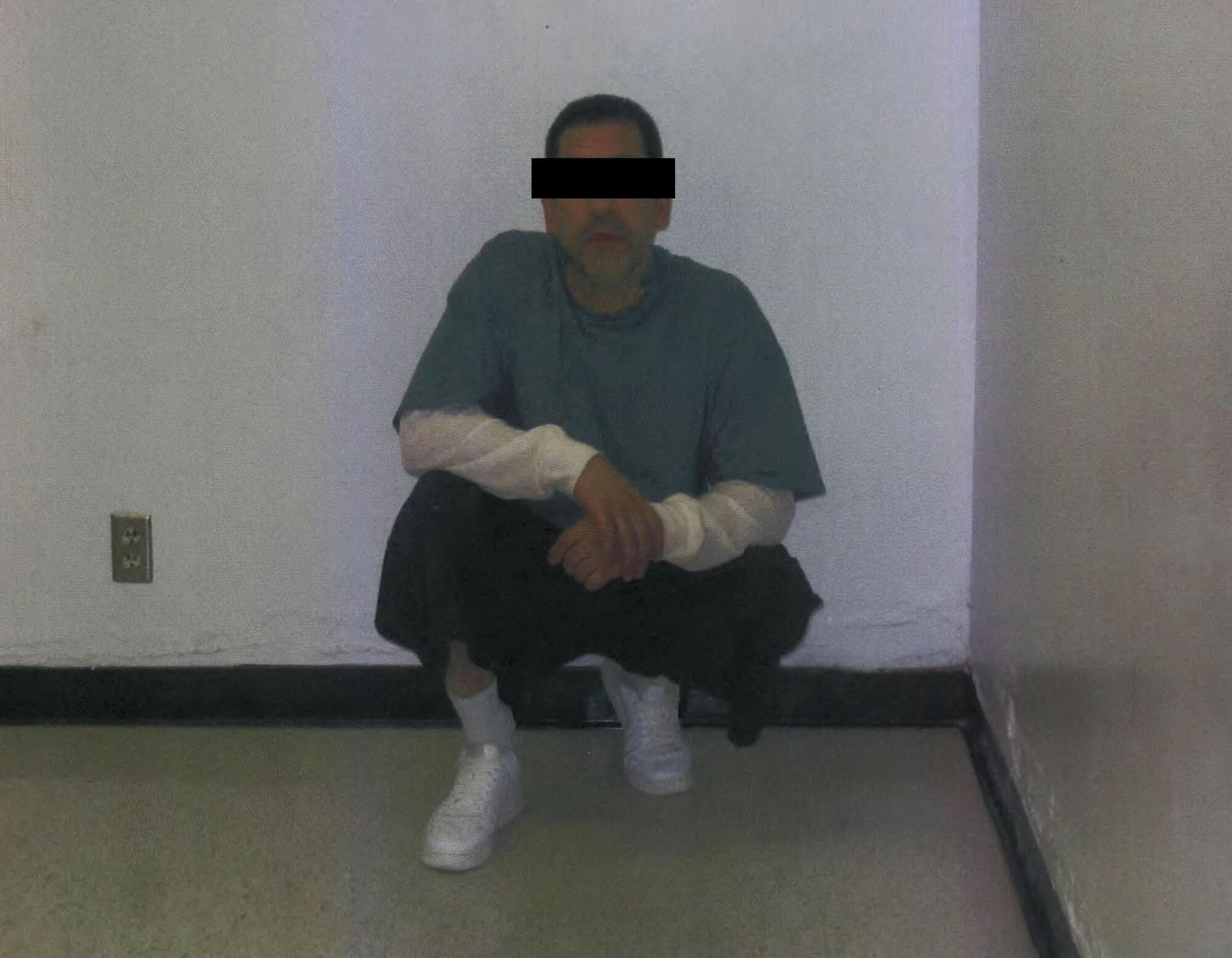

His name was Ralph “Perico” Rocha, the report said.

After six years of interviewing confidential sources and witnesses, including some who were inside the tattoo shop, a Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department homicide detective testified at a preliminary hearing that evidence indicated Rocha had ordered Rodarte’s death.

Yet 15 years later, Rocha has never been charged with the crime. Some law enforcement officials argued this was because the evidence was unreliable or lacking altogether. But there was another factor: Five months after Rodarte was killed, Rocha secretly became an informant for the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, whose agents used him to infiltrate negotiations between the Mexican Mafia and a Mexican drug cartel.

In interviews with law enforcement, Rocha admitted demanding money from a handcuffed Rodarte the night he was killed but denied ordering his death. Whoever pulled the trigger wasn’t taking orders from him, he said.

- Share via

“I never ordered nothing,” Rocha told The Times. “I could honestly say I never said, ‘Go do this, go do that, go kill this dude.’”

Rocha’s case illustrates the compromises that authorities make when cutting deals with high-level cooperators. Such informants often bring considerable baggage to the table. When evidence of a past crime surfaces, authorities must decide whether to prosecute a source who is helping them build cases — and on whom they have staked money and reputations.

The federal government paid Rocha nearly half a million dollars in taxpayer money. And county prosecutors spared him a life sentence after his handlers persuaded some of the highest-ranking law enforcement officials in Southern California that their star informant had turned the page on an admitted two-decade period of repeated criminality.

Part of that past was Rodarte. Even as ATF agents and detectives from the Sheriff’s Department’s Major Crimes Bureau were using Rocha to tape discussions of a drug trafficking alliance, a different group of detectives within the Sheriff’s Department was investigating his role in Rodarte’s death.

The homicide cops traced a chain of events back from the endpoint at the alley in Compton: A child’s abduction. A phony FBI raid. A high-speed chase. A bathroom lined with plastic. Men handcuffed and zip-tied and blindfolded.

The detectives kept coming back to Rocha.

The feds wanted his help to take down drug traffickers. The evidence of his involvement in Rodarte’s homicide was circumstantial and open to interpretation. It wasn’t as clear-cut as the cases he was making — drug deals recorded on tape. Courtroom-solid.

But what about the body in the alley?

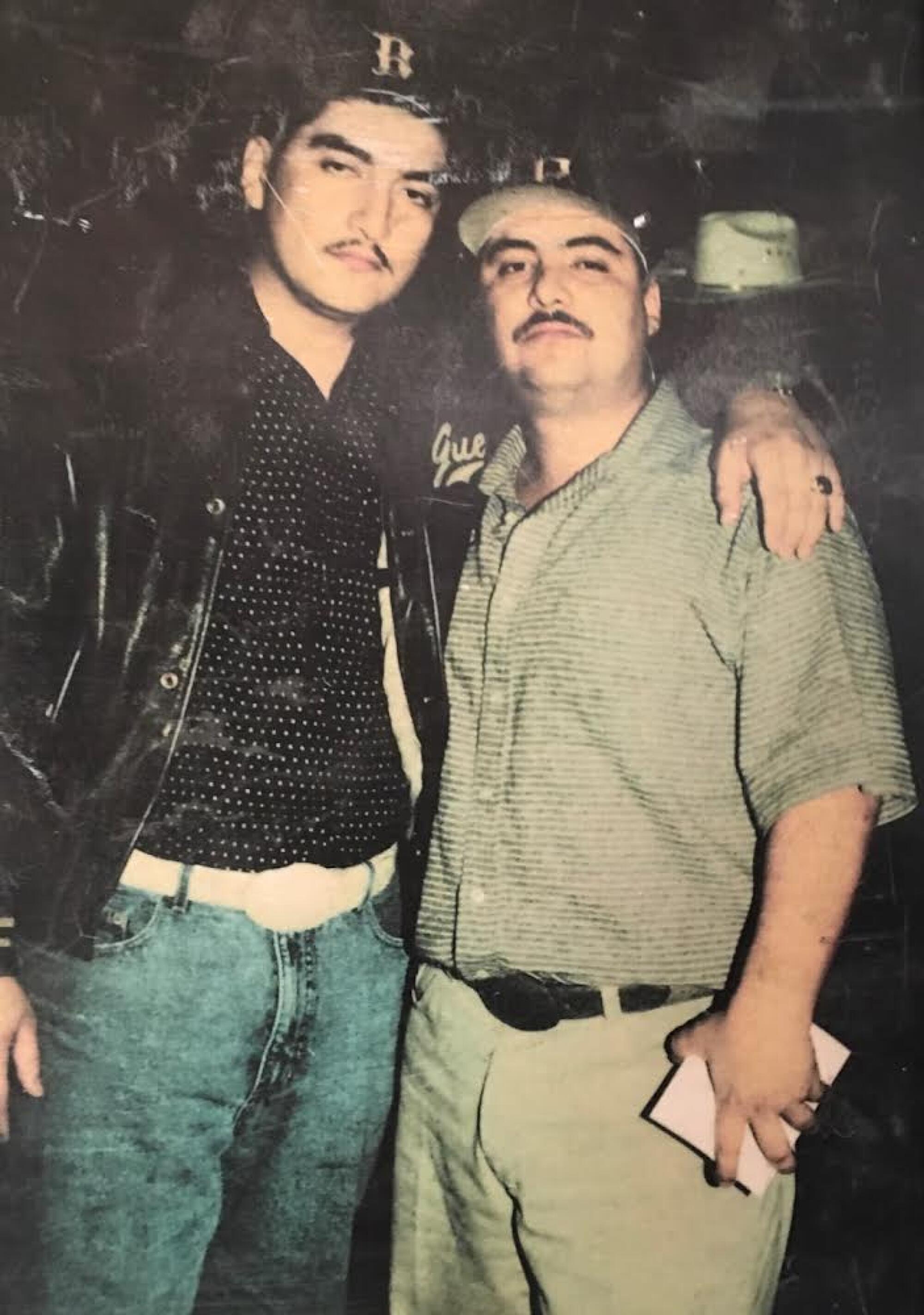

Rodarte was 3 when his parents brought him from Jerez, the city in the Mexican state of Zacatecas where his family had lived for generations, to the east side of South L.A.

He joined the local gang, 38th Street, and took the nickname “Bad Boy.” Convicted of manslaughter at 17, “he had to choose,” his brother, Roberto, said in an interview on the front porch of their mother’s home. “Be a no-one or be from somewhere. So he committed to 38.”

In 1992, Rodarte was released at 23 with the respect and connections that in his milieu only come from doing time, his brother said. He went legitimate — studied sociology at Cal State Dominguez Hills, developed businesses that sold drinking water and opened a restaurant on Central Avenue called El Solecito. He raised a family in Pico Rivera, but he also kept a foot in the underworld.

“Guys would parole, and they always wanted to meet my brother so he could do this favor, find this person, talk to that person,” Roberto Rodarte said.

In 2009, Rigoberto Villasenor, a member of 38th Street called “Pelon,” went to Lucio Rodarte for help, Roberto Rodarte said. Villasenor’s 17-year-old son had been kidnapped from his family’s Corona home, according to a Los Angeles police search warrant affidavit.

Lucio Rodarte suspected a fellow 38th Street member, Arturo “Crook” Alvarez. Alvarez, 34, led a strong-arm crew that collected money from vendors at the Alameda Swap Meet, witnesses told the detectives who investigated Rodarte’s death. Nestled in an old factory complex at the corner of Alameda Street and Vernon Avenue, the swap meet was the jewel of 38th Street’s territory, producing illicit “rent” payments that were kicked up to the Mexican Mafia.

“Every week, we need to come up with $5,000,” a member of Alvarez’s crew told sheriff’s detectives, according to a tape of the interview reviewed by The Times.

Rodarte had confronted Alvarez over collecting money from swap meet vendors. A witness told homicide detectives that Rodarte sold drugs and robbed rival dealers, but he drew a line when it came to extorting from people trying to make an honest living.

“God rest his soul,” the witness said of Rodarte. “I know he wasn’t the perfect man, I know he wasn’t a church-going man, but he did his thing otherwise quietly, discreetly.”

The witness told detectives he walked in on a meeting at the Rodartes’ restaurant after Villasenor’s son was kidnapped. He overheard Rodarte tell Alvarez, “They seen you, dog.”

Cameras from the home of Villasenor’s neighbor had captured Alvarez’s face before he pulled on a mask.

“Turn the boy in,” Rodarte said.

Six days after the abduction, Alvarez awoke to the sound of banging on the front door of his South Gate home.

“Open the door,” someone yelled. “FBI!”

Sledgehammer blows and two blasts from a shotgun took the door down. Three men holding “big guns with lights” ordered Alvarez, his wife, their children, ages 6 and 14, and his elderly parents onto their knees, Alvarez’s wife told sheriff’s detectives. The men wore tactical gear: ski masks, gloves, fatigues, bulletproof vests.

One of the men grabbed Alvarez and zip-tied his wrists, barking into a radio: “We have suspect, we have suspect.” They marched Alvarez in his plaid boxers to a gold Honda minivan, leaving his family behind.

The men who took Alvarez were not FBI agents but gang members, according to a court decision that summarized evidence at a trial. A South Gate police officer chased the van onto the 710 Freeway. It exited in South Los Angeles, blowing through red lights at speeds of up to 100 mph. The van slowed long enough for some passengers to jump out and run. It took off again. It pulled U-turns. It danced ahead of a helicopter’s searchlight. The line of police cars behind it grew.

A California Highway Patrol team finally forced the van to a stop at 55th and Hoover streets. The driver fled. In the back was Alvarez, his ankles and wrists bound, eyes and mouth covered with duct tape. Two bullets had been fired into his head.

One of the men ultimately convicted of killing Alvarez testified they planned to spirit him to Mexico and turn him over to military officials, who would interrogate him about the whereabouts of Villasenor’s son.

Three weeks after Alvarez’s death, Villasenor turned over a $150,000 ransom payment in Tijuana, and the boy was released in downtown Los Angeles, according to a search warrant affidavit and court papers filed by Villasenor’s lawyer.

By then, Rodarte was already dead.

On the last day of his life, July 27, 2009, Rodarte told a friend he needed to “talk to some people to clear something up,” according to testimony in the case of the man accused of killing him.

Rodarte knew he could face retaliation for Alvarez’s death. It was no secret, his brother said, that Rodarte “gave the word to take Crook out.”

Rodarte and his friend, Joe Padilla, drove to a Denny’s in Maywood, Det. Karen Shonka of the Sheriff’s Department’s Homicide Bureau testified at a preliminary hearing. Padilla waited in the car as Rodarte spoke with two men who arrived in a green Scion XB.

Rodarte returned to his car, handed Padilla his phone and wallet, and told him to take down the Scion’s license plate. The number Padilla wrote down, Shonka testified, was one digit off from a car registered to the wife of the owner of the Lost Angels tattoo parlor.

If anything happens to me, Rodarte told Padilla, remember the names Marcos and Clown.

Rodarte had known Efrain “Clown” Olmos since childhood, according to Rodarte’s brother, who had nothing but contempt for the man. Olmos, who came up in the same gang and served time with Rodarte in the California Youth Authority, was “a wannabe thug, a wannabe gangster,” Roberto Rodarte said, “a wannabe everything that, in the line of fire, he couldn’t be.”

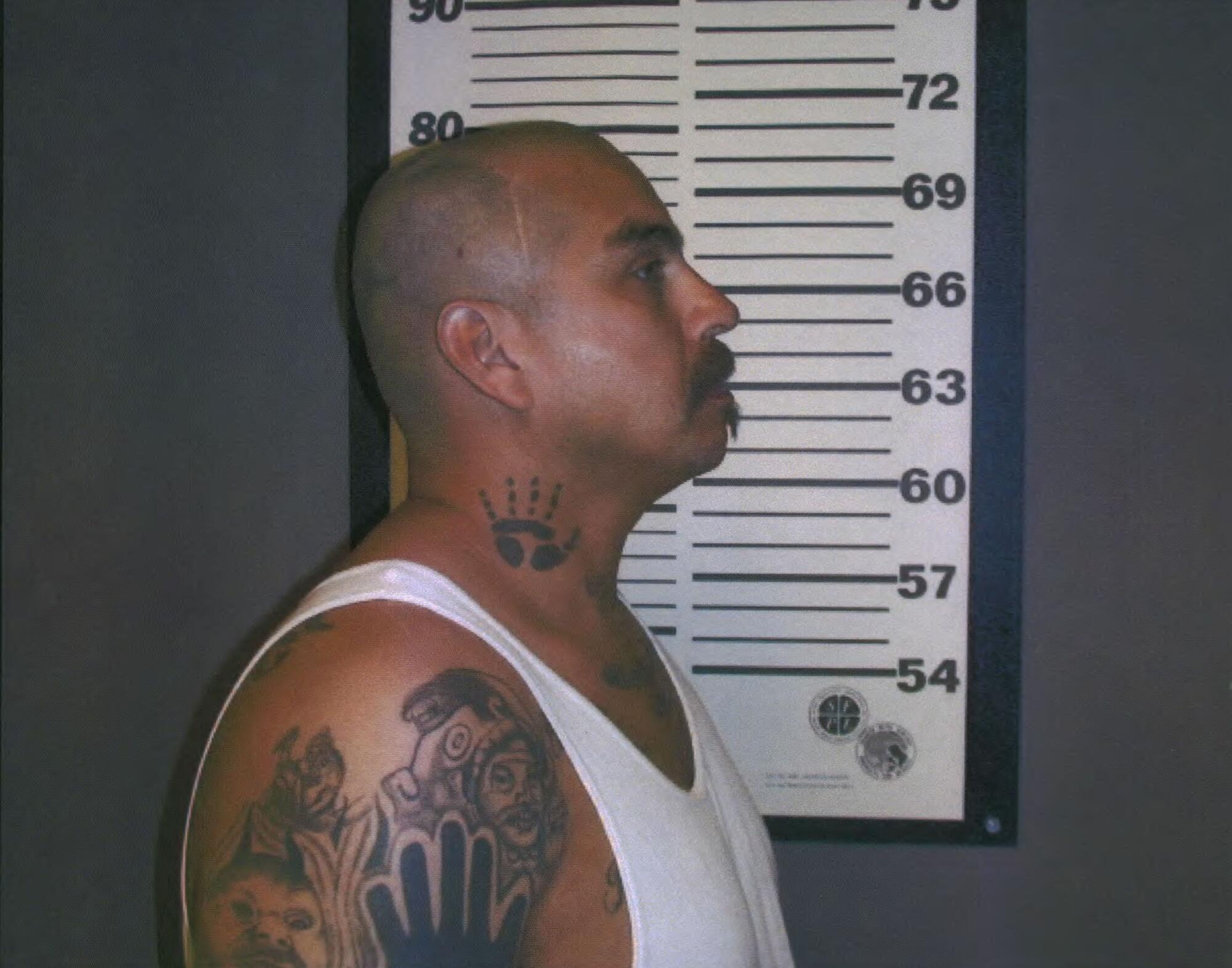

Olmos ran big — 6 feet 1 and 235 pounds — and favored flashy clothes and gold jewelry. Indicted in a 2000 case targeting the leaders of 38th Street, Olmos served six years in federal prison for distributing crack cocaine and possessing two AK-47s.

It was Olmos who, along with a member of the Florencia-13 gang, Marcos Lopez, brought Rodarte to the Lost Angels tattoo parlor, witnesses told homicide detectives. The moment Rodarte stepped inside, a man snapped a pair of handcuffs on his wrists and brought him before Rocha, who was reclining in a tattoo chair.

From speaking to sources who were inside the parlor, including Rocha himself, L.A. sheriff’s detectives pieced together the last hours of Rodarte’s life.

Olmos accused Rodarte of killing Alvarez, a sheriff’s detective testified at the preliminary hearing. Another man put a silencer-equipped handgun to Rodarte’s temple and, with his other hand, struck him in the face over and over.

Rocha asked Rodarte how much money he could pull together, according to an FBI report that summarized an informant’s account of the scene. When Rodarte said $20,000, the report says, Rocha replied: “Wrong answer.”

Rocha told the tattoo parlor’s owner to call his “carpet guy” because he might need to replace it, according to the FBI report. The bathroom had been lined with plastic, the detective testified.

“If you don’t want to see this guy get chopped up into pieces,” Rocha announced, according to the detective, “you need to leave.”

Before leaving, the FBI’s source heard Rocha tell Olmos it was his “mess” to clean up. Olmos began to shake.

Later that night, Olmos went to a carniceria run by the daughter of a Mexican Mafia member, according to federal drug task force records reviewed by The Times. Olmos was overheard saying Rodarte had begged for his life when he drove Rodarte to the alley in Compton. He told Rodarte to walk, the records say, then shot him twice.

Olmos returned to the carniceria a few days later. His own homeboys from 38th Street were trying to kill him, he told a group gathered at the store. Someone had called and warned he was next.

Eighteen minutes after midnight on Aug. 24, 2009, police found Olmos behind the wheel of his idling white Chevrolet HHR in Watts. He’d been shot four times in the head and once in the chest.

Three months passed. Rocha was arrested in an unrelated extortion case. Facing life in prison, he told detectives from the Sheriff’s Department’s Major Crimes Bureau that he wanted to talk. The detectives were thrilled.

“It’s amazing [what] you can do,” one said, marveling at Rocha’s access to Armenian organized crime figures and Mexican drug cartels, according to a transcript of the interview. “I’m talking about proactive stuff that would be on the street.”

The detectives set up a video camera. Rocha brought up a homicide. “I think he’s from 38,” he said referring to the dead man. He didn’t know Rodarte’s name, he told the detectives, only that he was from 38th Street and owned a restaurant that another Mexican Mafia member in the tattoo parlor at the time, Rafael “Cisco” Gonzalez Munoz, demanded that he sign over.

“You want to get out of here?” Rocha recalled telling Rodarte, according to the transcript. “You got to get 100 g’s.”

Rodarte refused. Thinking “this is going nowhere,” Rocha said he and Gonzalez Munoz went to a Jack in the Box down the street.

Rocha described the scene to sheriff’s detectives:

Olmos showed up “sweating bullets” with Lopez, the Florencia-13 member who’d met Rodarte at the Denny’s. They asked what to do.

“That’s your issue, homes,” Rocha told them. “Handle it.”

“But in your world, your organization,” a detective asked, “when you say, ‘Handle it,’ what does that mean?”

“That pretty much, probably, you know — smoke the dude,” Rocha told the detectives.

The sheriff’s detectives who debriefed Rocha in 2010 made a pitch to their higher-ups: Rocha could bring down not just the Mexican Mafia, but drug cartels and Armenian mob figures. The ATF agreed to fund and oversee what the bureau’s Los Angeles chief predicted would be an “unprecedented” investigation of organized crime in Southern California.

Brass from the ATF and Sheriff’s Department wrote to the Los Angeles County prosecutors who charged Rocha with extortion: Let him out so he can work for us. The district attorney’s office agreed. Rocha would be released, a potential life sentence swapped for a time-served deal on the two months he’d spent in jail. He’d wear a wire. He’d testify. He’d obey all laws.

He would even help solve the crime he was suspected of ordering.

The night of March 30, 2010, Rocha picked up Art Garcia in his silver BMW 745 Li. Rocha had told detectives that Garcia, owner of a Maywood nightclub, was in the tattoo parlor the night Rodarte was killed. Rocha said he was the one who held a gun to Rodarte’s head while beating him.

As they drove to a strip club, Rocha asked who killed Rodarte. According to an ATF transcript of the recorded conversation, Garcia said, “It was me and Clown,” referring to Olmos.

Garcia said he had asked Rocha, “You want to handle that though?”

“You said, ‘Yeah,’” Garcia reminded Rocha, according to the transcript. “You said, ‘Call me, you know, when this thing is done.’”

He assured Rocha it was “our secret alone,” the transcript says.

Rocha next met with Gonzalez Munoz, the other Mexican Mafia member who was in the tattoo parlor. The tape was running when Rocha brought up the scene at the Jack in the Box. Remember telling Olmos and Lopez to “handle that?” he asked Gonzalez Munoz.

“I told them, you know, don’t leave it in the open,” Rocha said of the body, according to a transcript of the exchange that was filed in Gonzalez Munoz’s federal case. “So how did it get in the f—ing open?”

Three years went by. The task force of sheriff’s detectives and ATF agents kept Rocha out of jail so he could tape discussions of an alliance between the Mexican Mafia and a cartel called La Familia.

After federal prosecutors in 2013 unsealed an indictment charging members of both organizations with drug trafficking, Shonka, the detective who investigated Rodarte’s death, confronted Garcia with the recordings from the wired-up BMW.

“Our goal is to go after this person that’s really bad,” she said, according to a tape of the interview. “And I think you know who I’m talking about. The one that’s got you here right now.”

“He intimidated a lot of people,” she said of Rocha. “He hurt a lot of people, he stole from a lot of people. He victimized many, many human beings. And he’s getting away with it. And you’re going to let him. You’re doing it right now.”

Garcia wavered. He spoke vaguely of being manipulated by Rocha “through intimidation, through threats.” But in the end, all he told the detective was: “I didn’t kill that dude or take him, and that’s my statement.”

Shonka arrested him on suspicion of murder.

At Garcia’s preliminary hearing, his attorney asked the detective if Rocha ordered Rodarte’s death.

“That’s what I believe, yes,” she replied.

Shonka, who has since retired, didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Subpoenaed by Garcia’s lawyer, Rocha invoked the 5th Amendment. Two days after he refused to testify, prosecutors dropped the murder charge and Garcia pleaded no contest to kidnapping, court records show.

Released from prison in 2022, Garcia said he served his time and didn’t want to discuss the case. He was willing, however, to talk about Rocha, whom he called “a fraud who utilized and betrayed his organization and the government for self-preservation.”

By bargaining with Rocha, prosecutors and police “paid more for what they got,” Garcia told The Times. “He was out in the streets, trying to create stuff to give to the government, and at the end of the day they gave an unworthy informant a deal he didn’t deserve.”

Just before the cartel case went to trial in federal court, defense attorneys obtained a secret set of tapes. In the recordings, Rocha disparaged his handlers as dishonest and unethical; his associates in the Mexican Mafia as stupid; the government’s crime-fighting strategies as corrupt.

The closest he came in the tapes to discussing Rodarte was mentioning a man held captive in a tattoo parlor. “They killed him, threw him and we all left,” Rocha said. “That was some dumb s—. That wasn’t even our s—.”

Rocha did not testify at the trial, which ended in acquittals for most of the defendants, but his handlers were questioned on the witness stand about Rodarte’s death.

Steven Kays, one of the Major Crimes detectives who flipped Rocha, testified he told his colleagues in the homicide bureau, “If you could prove that he was involved in the murder, then go forward.”

Shonka wanted the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office to charge Rocha with murder, according to emails exchanged between prosecutors.

Shonka brought the case to Deputy Dist. Atty. Kenneth Lynch, who recounted what happened next in an email to the supervisor of the office’s organized crime division. Kays called Lynch and said Rocha had been granted immunity. He made clear to the prosecutor that Rocha was in a witness protection program and due to testify in federal court.

In the end, prosecutors decided to do nothing. Lynch, who didn’t reply to a request for comment, wrote off the witnesses who spoke to Shonka as accomplices, their testimony uncorroborated by independent evidence. He didn’t charge Rocha with murder — but he didn’t formally reject the case either.

Marc Beaart, director of the district attorney’s Bureau of Fraud and Corruption Prosecutions, told The Times he could find no record of prosecutors giving consideration to Rocha’s status as an informant when weighing whether to charge him.

In an interview, Kays, now retired, acknowledged Rocha came with “a lot of baggage.” But there was “no indication Rocha was responsible — actually involved in a murder,” Kays said. “He didn’t kill anybody, is what I’m trying to say.”

Interviewed from an undisclosed location in the witness protection program, where the U.S. Marshal’s Service guarantees his safety at public expense, Rocha said he didn’t know how Rodarte ended up in the tattoo parlor that night 15 years ago.

“I just got pulled into it right then and there,” he told The Times. It was all “a bunch of bull— I didn’t want to deal with.”

Rocha said it wasn’t his style to order anyone to do anything — much less a murder. “I’d probably be more like, ‘Go ahead, dude. Do whatever you think you need to do.’ Of course a lot of people would take that to the extreme to please us, but that’s not what I’m saying.”

After the federal case was unsealed, Shonka was allowed to interview Rocha. She asked if anyone ever admitted killing Rodarte. Rocha said he didn’t remember. He told her he didn’t “pay much mind” to the whole thing, according to a tape of the interview.

“Obviously this drug cartel and all that means the world to these guys,” Shonka said of his handlers in the Sheriff’s Department and ATF. “And that’s fine for them. But I think our job, trying to solve murders — it’s the ultimate crime to me, anyway.”

Rocha chided the detective. She saw the world in stark terms, he told her. She wanted him to say he ordered someone to do a terrible thing and they did it. In “the real world,” he said, nothing was that simple.

“I know you want it more black and white,” he said. “But it’s not.”

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.