- Share via

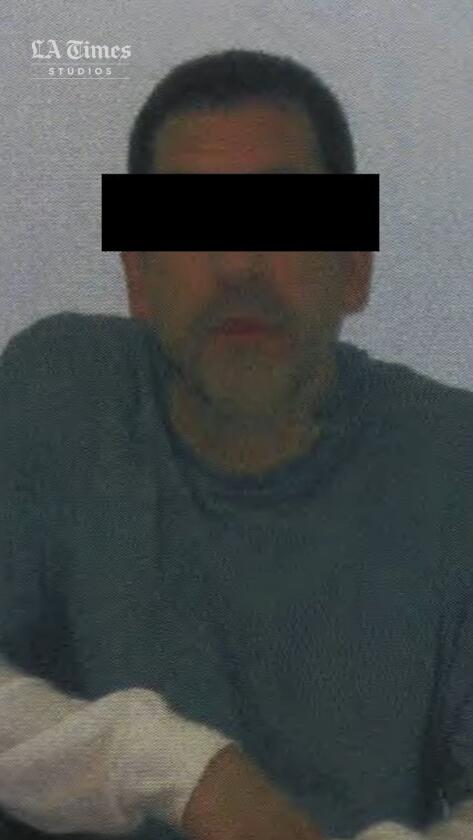

In a city full of secrets, Ralph Guy Rocha kept more than most.

As a member of the Mexican Mafia, Rocha was pursuing a deal with a drug cartel in Mexico called La Familia. The cartel had proposed a trade: an unending supply of methamphetamine if the Mexican Mafia protected the cartel’s leaders in U.S. prisons.

What no one in either criminal organization knew was that Rocha was an informant for the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, whose agents were using him as a walking tape recorder to monitor the negotiations as they unfolded.

But Rocha kept secrets from the agents, too. After a long day’s work of making tapes for the federal government, he went home and made recordings of his own.

In the tapes, disclosed here for the first time, Rocha told a very different story from the one agents and prosecutors presented in a 2013 indictment alleging the Mexican Mafia and La Familia were entwined in a sinister, transnational alliance.

- Share via

In his tapes, Rocha said his associates in the Mexican Mafia were so bumbling and dim-witted, they could not have pulled off the cartel deal had he not taken charge with help from his government handlers. And those agents and detectives were dishonest and unethical, he claimed, playing up the specter of the Mexican Mafia to justify their salaries and high-level assignments.

“The badder the monster got to be to have this new task force,” he said.

Rocha’s handlers in the ATF and Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department said they didn’t exaggerate the danger of the Mexican Mafia, which they considered a significant threat to the public and which warranted using informants such as Rocha to disrupt ongoing crimes.

The proposed alliance between the Mexican Mafia and La Familia was “a very serious proposition,” one of his handlers told The Times, and could not have been broken up had Rocha not infiltrated the negotiations.

Authorities make deals with criminals every day, trading money, reduced prison time and other benefits for information and access only an insider could provide. These bargains are typically negotiated in closed courtrooms and recorded in sealed files. What makes Rocha’s case unique is that he created an unauthorized account of his tenure as a high-level informant.

Over about a dozen hours of tape, he narrates his rise within the Mexican Mafia, explains his decision to defect and describes how the government used him to take down a network of gangsters and drug traffickers on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border beginning in 2010.

His handlers have theories about why he made the tapes: They were an insurance policy in case the authorities reneged on his deal. They were a way to blow off steam amid the stress of working undercover. They were an early stab at a screenplay.

Rocha was trying to make his life sound “as interesting and riveting as possible,” a Los Angeles County sheriff’s detective wrote in a memorandum to prosecutors after reviewing the tapes, “very similar to the way that Henry Hill [Italian Mafia informant] did when he told his story for a book deal and later the hit movie ‘Goodfellas.’”

In a recent telephone interview from an undisclosed location in the federal witness protection program, Rocha offered his own explanation: “I just wanted proof I existed.”

“Them tapes, I didn’t know what the hell was happening,” he told The Times. “The world was collapsing on me. Were they going to kill me? Was I going to get sniped by a secret agent? I just needed proof that this happened, I guess.”

It was late 2009, and Rocha was lying in his bunk at Men’s Central Jail in downtown Los Angeles. Forty-two years old, facing a life sentence for extortion, “all my life up to that point … seemed to come into focus,” he said in one tape made without his handlers’ knowledge.

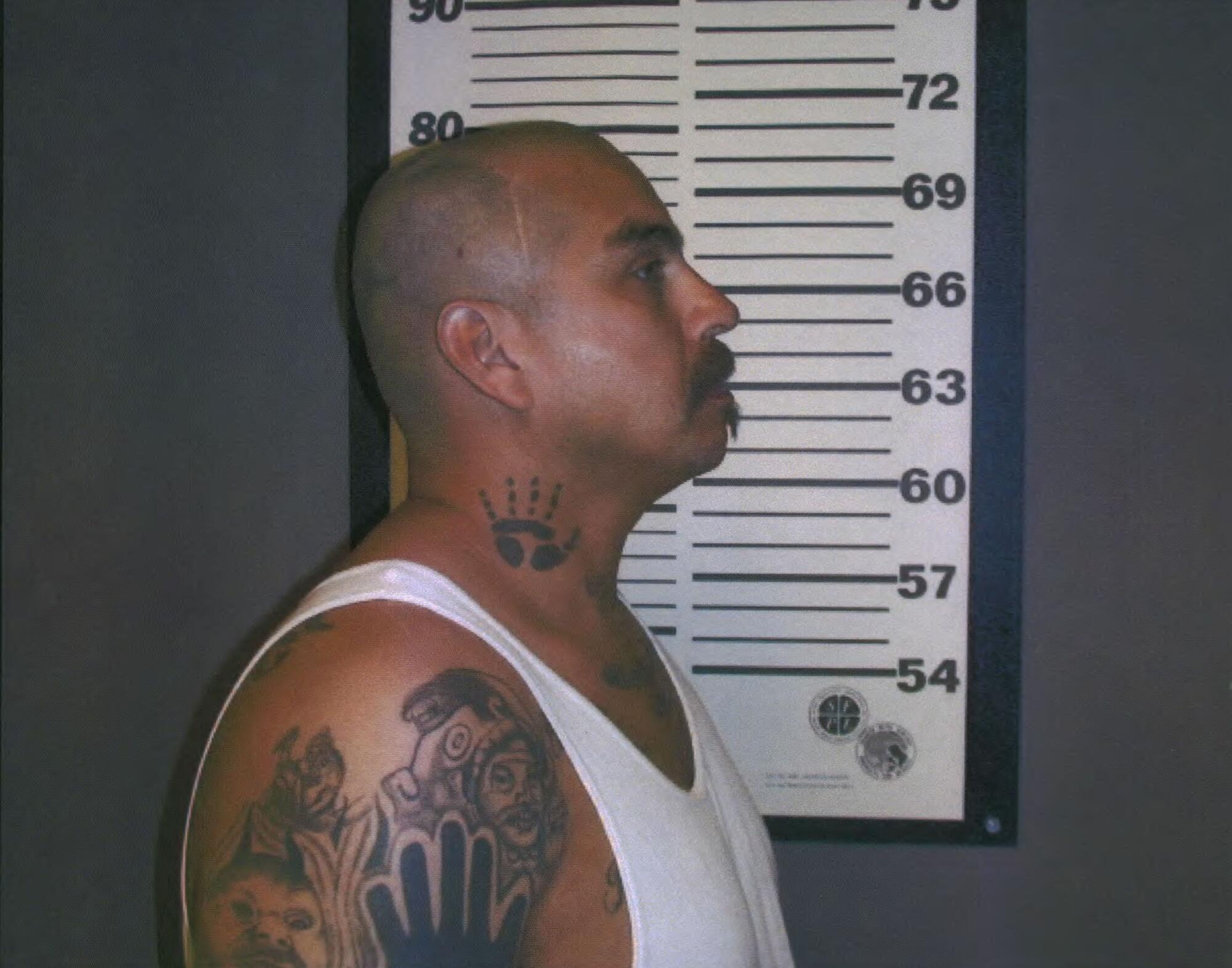

Son of a heroin addict father. Teenage gangster. State prisoner. At 23, the Mexican Mafia — “the youngest carnal to ever be made,” he boasted.

The 140 or so men who make up the Mexican Mafia call one another carnales, or brothers. In Southern California, the cradle of street gang culture, the organization is spoken of with reverence and fear. It is not the Mexican Mafia, but La Eme — Spanish for “The M.”

The first time Rocha recognized the power of the Mexican Mafia was also a lesson in its limitations. In the early 1990s, homicide rates were at an all-time high. “Homies were just shooting at anybody,” he recalled in his tapes. “If you went into a neighborhood and they didn’t know you, they’d shoot at you.”

The Mexican Mafia summoned gangs en masse to meetings at parks, where the word went out: Anyone caught doing a drive-by shooting would get the “green light.” Their homeboys in jail and prison would be stabbed and beaten until the Mexican Mafia said otherwise.

When the gangs complied, Rocha said, he realized the organization could manipulate the levers of political power through violence.

“We’d done something that no organization, legit organization, has done,” he said. “The LAPD. All your little charitable nonprofit organizations, all the gang violence little organizations. All the counselors that go around. We did what they couldn’t do, what they probably spend millions and millions of dollars on to do.”

Other carnales were skeptical, Rocha said. They still considered the organization a prison gang that existed to supply its incarcerated members with drugs and creature comforts to ease the misery of doing time.

“There was just a lot of things I was trying to do that I actually thought gangsters did,” Rocha said. “Go legit, get businesses, get politicians.”

Rocha believed the organization was being held back by those who didn’t share his vision. Take the drug business: A distributor from the Sinaloa cartel promised to supply them with as much cocaine as he could sell. Rocha recalled passing out kilograms to other carnales, telling them, “We could lock down all the drug trade, everything. But you got to be able to come back with the money to buy another key.”

“Everybody that I gave it to, nobody came back with money.”

After the Mexican Mafia squandered the lucrative drug connection, Rocha moved to “taxing” dealers in his home city of Norwalk. “First I went and I robbed everybody I knew,” he recalled. He and his crew kicked in doors, “no mask, no nothing,” and handcuffed everyone inside. “Throw ‘em on the ground, search the pad, take all their guns, all their drugs. Whatever jewelry we wanted.”

Rocha left them with a key to the handcuffs and a message: “You can’t sling drugs, can’t do nothing, unless you do it through me.”

In 1995, a grand jury indicted Rocha and a dozen others in the first racketeering case targeting the Mexican Mafia. He pleaded guilty and spent the next 12 years in federal prison.

Released in 2007, Rocha believed the Mexican Mafia’s reputation had been diminished. He was determined, he said, to “get the Eme back to where it’s supposed to be.”

He and another Mexican Mafia member, Rafael “Cisco” Gonzalez Munoz, called a summit of gang leaders from South Los Angeles, Compton, Long Beach and Wilmington at a nightclub in Maywood. They ordered the gangs to start “taxing” local businesses, according to an FBI report. Only large companies — “Ralphs, Blockbuster, Burger King” — got a pass.

Next they turned their sights on Gonzalez Munoz’s hometown. At the eastern end of the San Gabriel Valley, La Puente was controlled by Maria Llantada, the wife of an imprisoned Mexican Mafia member. Rocha told detectives that he and Gonzalez Munoz kidnapped Llantada’s brother, releasing him only after she paid a $30,000 ransom, according to a Los Angeles County sheriff’s report. Her brother turned over an additional $40,000 after selling a car, Rocha said, according to the report.

After Llantada was overheard on a wiretap plotting to kill Rocha and Gonzalez Munoz, detectives found an Uzi in the trunk of her Ford Fusion and arrested her. She pleaded guilty to attempting to murder the two men and is now serving 19 years in prison.

In his tapes, Rocha said he was also doing business with Armenian crime figures in Glendale and was in the early stages of dealing with a Mexican drug cartel. But what got him arrested in 2009 was a more mundane affair.

A bumbling, drug-addicted thief stole 46 pounds of marijuana from a car that had been left overnight at an auto repair shop in South Gate. The thief later told police he sold the marijuana for $8,000, gave $2,000 to an accomplice, bought some meth and gambled away the rest at the Commerce Casino.

Then a man showed up at his family’s home with a message: He’d stolen from the Mexican Mafia. His family had two days to come up with $30,000.

After borrowing from relatives and tapping credit cards, the thief’s sister turned over the cash in a gray bank bag to a man at a TGI Friday’s, she told detectives. Two months later she got a call from a man who identified himself as Perico, Spanish for parakeet — Rocha’s nickname.

He said her brother owed $40,000 more. “If the air that your brother breathes is not worth the $40,000,” she recalled him saying, according to a sheriff’s report, “then give him to us.”

She went to the police. Sheriff’s detectives pulled over Rocha on the freeway and ordered him out of his silver Chrysler 300 at gunpoint. In his home they found a gray bank bag containing $3,000, according to a police report.

Booked for extortion on Nov. 19, 2009, Rocha recalled thinking that, even if he beat the case, “I’m going to do the same f—ing thing. Yeah, so I was like, it’s over with.”

He told the detectives he wanted to talk.

Over 12 days in 2010, Rocha recounted to investigators two decades’ worth of drug deals, shakedowns, kidnappings and shootings. Leaders of the ATF and L.A. County Sheriff’s Department then made their pitch to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office to use Rocha as an informant.

“This is an unprecedented opportunity to penetrate into criminal organizations that have plagued both our prisons and communities,” John Torres, then supervisor of the ATF’s Los Angeles office, wrote in a letter reviewed by The Times.

In a memorandum marked “CONFIDENTIAL,” Lee Baca, then sheriff of Los Angeles County, listed some of the crimes Rocha could help thwart: “Murder, money laundering, extortion, kidnapping, murder for hire, life threatening extortion, narcotic and weapon trafficking, as well as violations of the RICO statute.”

“All of the investigators believe that not only is Rocha being truthful about his account of criminal activities,” the sheriff wrote, “but he is sincere in his desire to assist law enforcement in dismantling the criminal organizations to which he has access.”

Prosecutors agreed to let Rocha out of jail. If he obeyed all laws, stayed in contact with his handlers and testified at all court proceedings, his punishment would be reduced from life in prison to a time-served deal for the two months he’d spent in jail.

Released after pleading guilty to extortion in a sealed courtroom under a “John Doe” pseudonym, Rocha went to work for a task force of ATF agents, sheriff’s detectives, prison investigators and local police. They wired Rocha’s BMW 745 Li with microphones and gave him a recording device resembling a key fob.

His handlers were Steven Kays, a sheriff’s detective who arrested Rocha for extortion, and John Ciccone, an ATF agent who had made a career out of investigating outlaw motorcycle clubs. Both men had two decades of policing under their belts when they convinced their superiors to use Rocha as an informant.

“We had to give it a shot,” Ciccone, now retired, said in an interview. “In order to make any impact on these types of organizations, you got to go out on a limb and see what you can do with a guy like this. It’s the only way to do it.”

But they soon learned the criminals Rocha knew best were already under investigation. His Armenian associates were being tracked by a task force in Glendale. Gonzalez Munoz was indicted in a take-down of San Gabriel Valley gangs.

“Everything was pretty much coming to a dead end,” Rocha said. “Until this cartel s— came up.”

A cartel called La Familia was producing huge amounts of methamphetamine in the western Mexican state of Michoacan. It needed protection in U.S. prisons and foot soldiers to collect debts and commit murders on American streets.

The Mexican Mafia could provide on both fronts, for a price — and the man representing them in negotiations with the cartel was Rocha.

First of three parts. Thursday: The informant and the cartel.

More to Read

Sign up for This Evening's Big Stories

Catch up on the day with the 7 biggest L.A. Times stories in your inbox every weekday evening.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.