As COVID-19 cases surge, L.A. librarians join the ranks of contact tracers

- Share via

Lupie Leyva is good at tracking things down. A kind of detective, if you will.

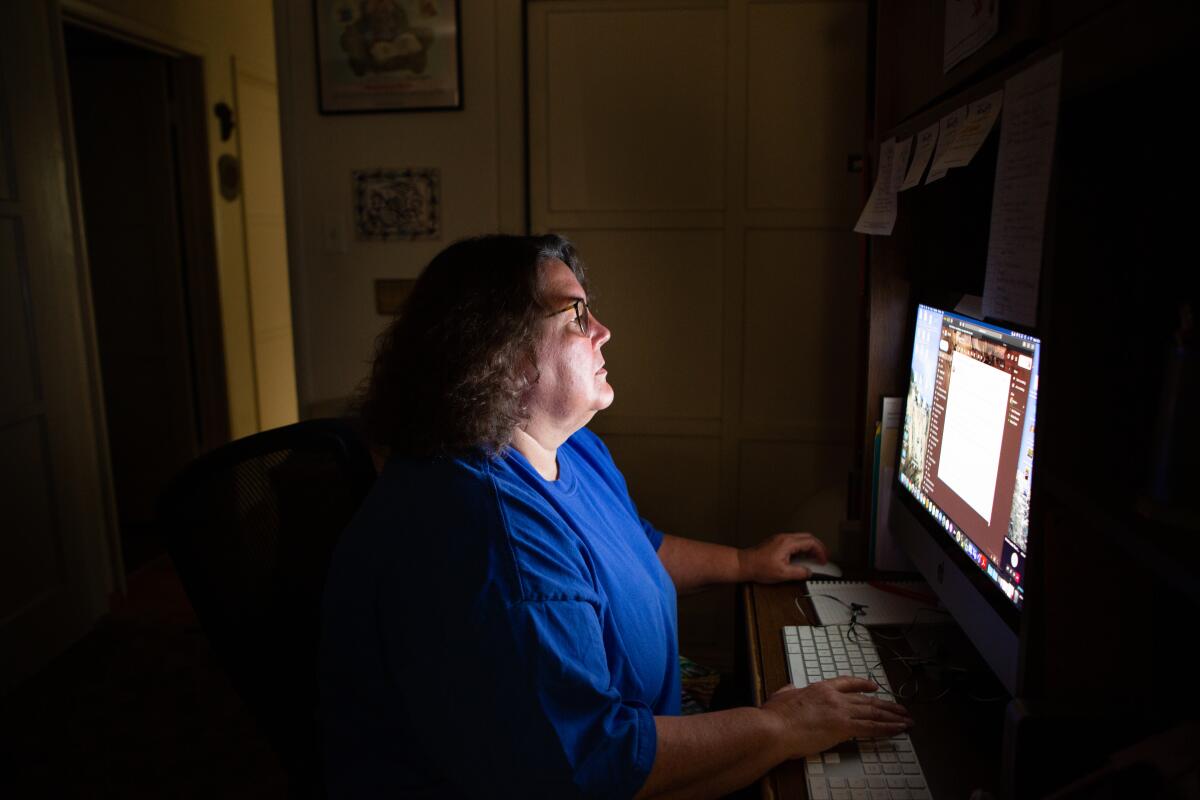

She’s organized and meticulous, curious and tech-savvy. For the last nine years, it has served her well as senior librarian and manager at the Robert Louis Stevenson Branch Library in Boyle Heights, where no book — however obscure — can escape her once she’s on the case.

Now, Leyva is using those skills to help fight the spread of the coronavirus. The 46-year-old is doing contact tracing of people who have tested positive in an effort to reduce their chance of infecting others.

“The reason I volunteered for contact tracing is that it’s really the same thing” as being a librarian, Leyva said. “It’s still helping people, it’s helping my community, it’s trying to get my community back to normal so that people will feel comfortable going back into the library.”

As California and other states confront a surge of coronavirus infections, deaths and overwhelmed hospitals, about 500 staffers at the Los Angeles Public Library have responded to a call to participate in the Disaster Service Worker Program. It calls on public employees to drop or expand their usual job duties to help agencies and organizations carry out an emergency response. The workers are assigned jobs within their scope of training, skills and abilities.

About 75 librarians and staffers are part of the contact tracing project.

In some ways, it is a stereotype-busting mission for a group of workers often portrayed in Hollywood movies and TV shows as reliable and fastidious, wise and quick to shush loud talking — but rarely heroic.

“Library staff bring empathy, commitment and a relentless focus on community and service,” said John F. Szabo, city librarian of the Los Angeles Public Library. “They’re used to stepping up, being nimble and adapting services to address real needs. So while I’m wowed by the incredible way in which Los Angeles Public Library staff have served the city as disaster service workers, I’m not at all surprised.”

Leyva grew up a bookworm in Boyle Heights, just blocks from the Robert Louis Stevenson Library. She translated the English world into Spanish for her immigrant parents and others.

“Growing up being an immigrant child mediator, you understand the power of helping someone have access to the information that they need,” Leyva said.

Officials are hoping public behavior changed toward the end of June and early July, but they won’t know how that plays out for several more weeks.

Latino and Black people have been the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic. In L.A. County, the two groups have twice the mortality rate of white residents, with more Latinos dying of COVID-19 than Black people. Latino and Black people disproportionately work as front-line workers in low-paying jobs that force them to leave home and interact with the public.

Library staff have volunteered at cooling centers and COVID-19 testing and shelter sites for people experiencing homelessness. They’ve delivered meals to senior Angelenos and other high-risk people. They have translated critical resources and information about the coronavirus to the city’s diverse populations in dozens of languages including Spanish, Chinese, Russian, Japanese, Farsi, Armenian and Korean. Most have volunteered to do this work, but they’re still getting paid a salary.

But contact tracing is where their particular set of skills might be most uniquely useful. It works like this:

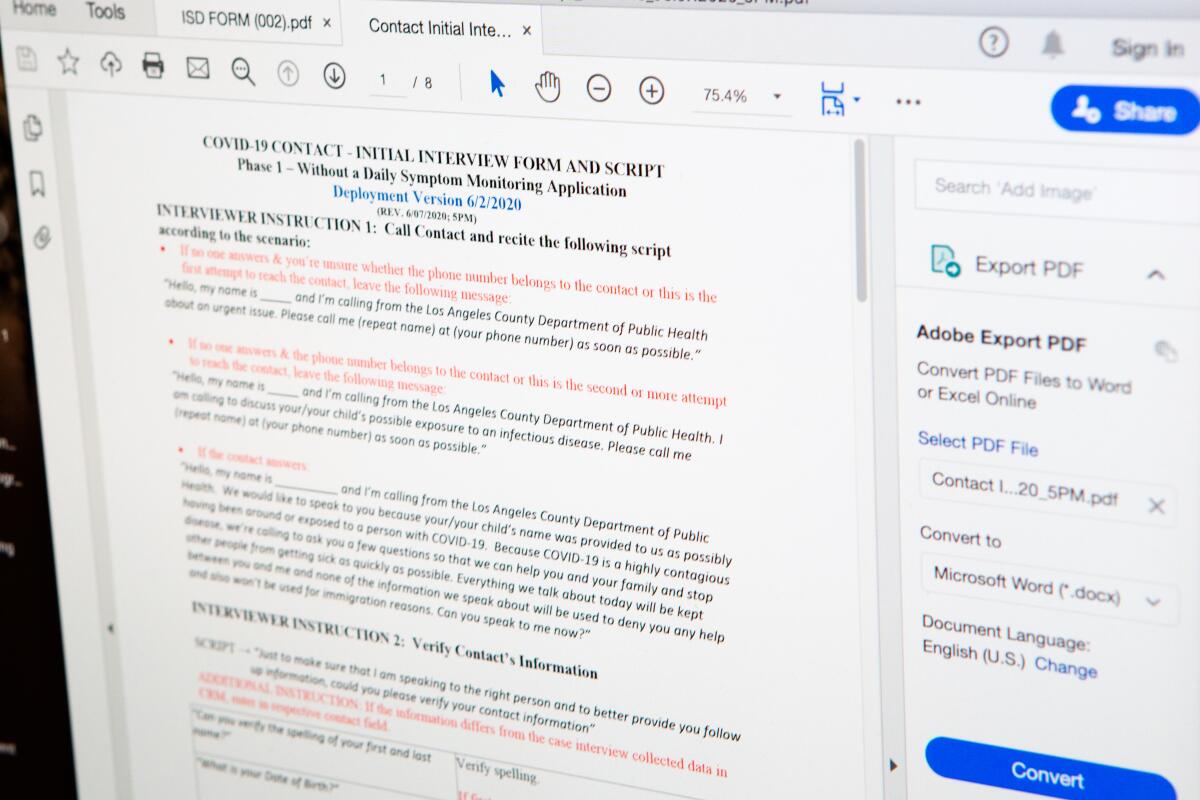

Librarians doing contact tracing will call the person who tested positive for the coronavirus and ask for personal information that is kept confidential. The librarian may then connect the individual to medical care and support resources.

Contract tracers will ask individuals what places they’ve been to and with whom they’ve spent time recently and then call those people. The contact tracers will tell them they were exposed to the virus and encourage them to get tested and quarantine to protect others. They will ask what places the individuals recently visited. In a few days, they will follow up to see if the people developed symptoms or need help.

For Leyva, just one call has produced a web of more than a dozen people who might’ve been infected by a positive case.

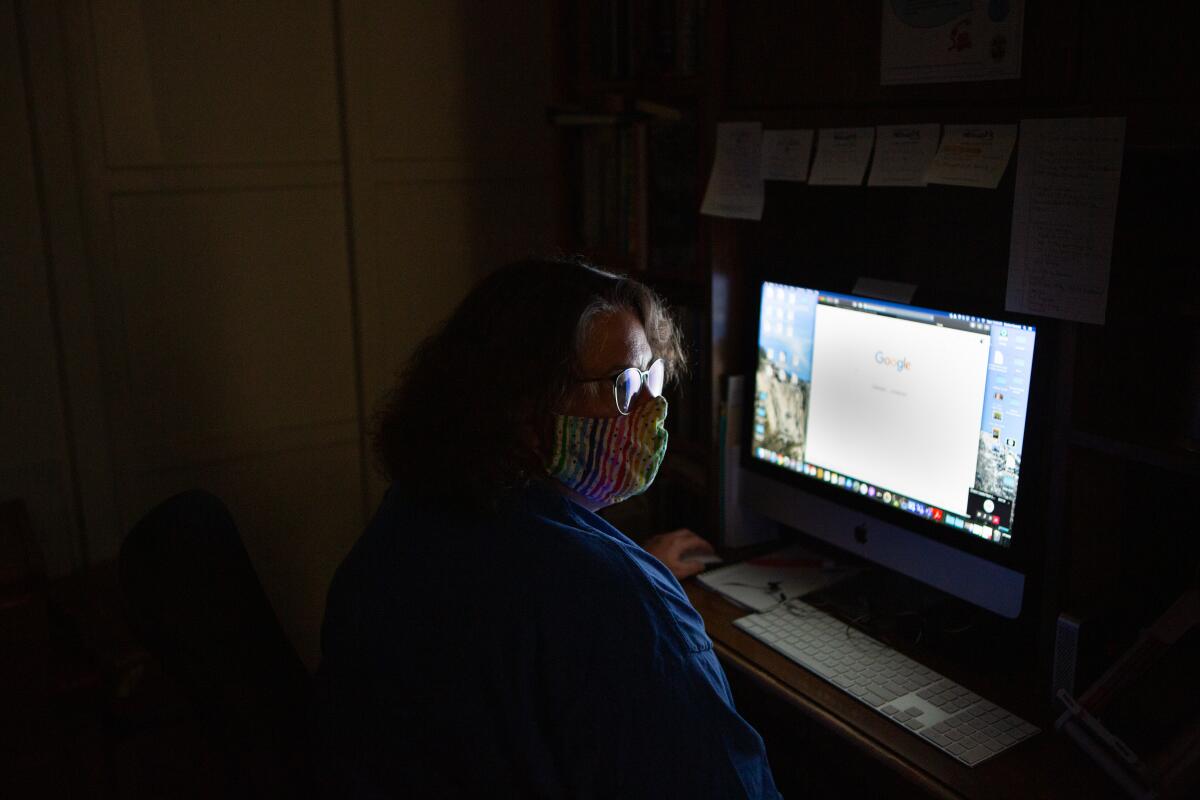

Denice Nossett, a senior librarian at the Wilmington Branch Library, said she felt she had to serve during the pandemic.

“It’s in my DNA to help people, and that’s one of the reasons I became a librarian,” said Nossett, 56, who is leading a four-person team of contact tracers. “That’s what you do in the library, day in and day out; you’re helping people.” And slowing the spread of COVID-19, she said, is one way of lending a hand.

The 28-year veteran of the L.A. Public Library has sticky notes taped above her home desktop with phone numbers for IT support and for language interpretation services. A poster of children’s book author Rosemary Wells hangs on one wall, and a poster of Harrison Ford for the American Library Assn. hangs on another.

Helping to curb the spread of the virus is personal for Nossett. She knows eight people who have been infected. An aunt and a longtime family friend died. She doesn’t want more people to suffer that fate.

Nossett said that in nearly three decades, being a librarian has taught her more than a few things that have proved helpful for contact tracing. Patrons often share very personal details about their lives, and librarians need to show empathy while also guarding people’s privacy.

“If a patron comes up to me at the library and says, ‘I just found out I have cancer and I need information on treatment,’ the first thing I’m going to say is, ‘I’m so sorry. Please let me help you with that’.... It’s important tracers have empathy,” Nossett said.

Becoming a contact tracer requires a weeklong training that Leyva described as akin to an “online college class,” with self-learning modules, live webinar lectures, homework, quizzes, exams and practice interviews. She learned about epidemiology and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

The contact tracers also learn how to handle people who are dismissive or reluctant to share information that could help halt the spread of the coronavirus.

“If people don’t want to talk to you, then they don’t want to talk to you,” Leyva said. “You do the best you can to try to talk to everyone, but it’s certainly not an obligation.”

But Leyva gets it: Phone scams are not uncommon, including during a pandemic that can spawn opportunism, so she understands people’s reluctance to provide personal information in that manner.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom defended his reopening decisions and adopted the same argument made by many critics of his original order: The consequences of the COVID-19 shutdown for the economy and mental health were too great to ignore.

When she comes across people who are reluctant to talk, she just tries her best.

“You remind them that it’s for the good of the community. You remind them that it’s a way you can help keep your friends, family and other people from getting sick,” she said. “But not everyone is going to want to answer your questions … so you thank them for their day and move on.”

The more common problem, Leyva said, is people simply not picking up the phone. After more than one attempt, she’ll leave a voice message that might sound something like this: “Hello, my name is Lupie Leyva and I’m calling from the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health. I am calling to discuss your/your child’s possible exposure to an infectious disease. Please call me … as soon as possible.”

With libraries closed, L.A. librarians now work from home to help people find free ebooks, music and movies during the coronavirus crisis.

When the pandemic closed L.A. libraries in March, Leyva transformed her family room into a home office. She made a makeshift desk out of a folding table, where she had many online meetings with other librarians to figure out how to virtually serve their communities from home. They promoted online resources and launched their weekly “Ask a Librarian” program in Spanish.

Eventually, her home office began to reflect the increasingly dire situation. Pinned to her wall are COVID-19 fact sheets. “10 things you can do to manage your COVID-19 symptoms at home,” reads one. “Share facts about COVID-19,” reads another. Next to them is tacked a daily reminder: “One thing at a time.”

Leyva’s work-from-home uniform often consists of jeans and a blue L.A. Public Library T-shirt that she said she would wear to the “happiest place on Earth” if Disneyland weren’t closed because of the pandemic.

Many essential workers — cashiers, truck drivers, meat packers — are Latino. They can’t stay home. And they’re being hit hard by the novel coronavirus.

“I think for us as librarians, this fits really well with what we do,” Leyva said of contact tracing. “When we went through the training, a lot of the interview techniques, we’re really familiar with.”

In the last few weeks, more than 10,000 contact tracers completed their training as part of California Connected, the state’s contract tracing program and public awareness campaign. Of those, more than 2,700 are in Los Angeles County. About 75 staffers from the L.A. Public Library are giving up their usual duties for at least three months to work full time as tracers.

It is an important job to keep the economy-crushing virus from spreading further.

“Case investigation and contact tracing are core disease-control strategies to break the chain of transmission and prevent further spread of the virus,” said a representative for the Los Angeles County Department of Public Health.

Doing contact tracing in Spanish means extra work. Interviewers like Leyva are given scripts to read to the people they call, and she’s opted to translate hers because the county doesn’t provide revisions in Spanish quickly enough.

It’s not so easy to translate on a call the technical terminology the county and the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention use, she said. But the stakes are high.

“Even though I’m not going to be a librarian for the next three, maybe more, months, it’s still … helping my community with what it needs right now,” she said. “Sometimes we help our communities at the reference desk … but right now what’s needed is this contact tracing, and we have skills that we can put to use doing this.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.