- Share via

The small brick plaza in front of the Pella, Iowa, public library was teeming with people. A gray-haired woman in a T-shirt stood stoically beside a large banner bearing a Bible quote with chapter and verse notation. There were a handful of other signs in the crowd. I can’t quote any of them because I kept my head down as I entered the plaza.

Inside the library, there were event posters with my face on them. I didn’t know if I’d be recognized in the crowd — or clocked as transgender. It occurred to me that in Iowa you don’t need a permit to carry a gun — open or concealed. A current of people was funneling into the library, and I joined them. I sensed, eerily, that some who were entering alongside me were protesters. I didn’t turn to look.

The event room was filling up fast, despite the fact that library director Mara Strickler held off on posting my visit to social media until three days before, opting instead for a word-of-mouth campaign. The crowd was mixed — age-wise and gender-wise — and overwhelmingly white (Pella, population 10,500-plus, is 95% white). A friend of mine who’d come from Iowa City told me later that some people in the back were giving out copies of my 2022 book, “This Body I Wore,” which had just come out in paperback. The gray-haired woman in the T-shirt filed in and took a seat.

I found Strickler, who said there were only a few protesters inside the room and that I wouldn’t be using a microphone. She had a gift for me, and hoped I’d stick around long enough to receive it. Until then, it would just be me, my book and my naked voice in a packed room where I had no idea what was going to happen.

:::

Last summer I embarked on a red-state library tour: visiting, free of charge, any library that invited me to do a book talk and presentation on the freedom to read. The tour was an idle thought I entertained early in 2023 — an extravagant, albeit enticing, “what if?” — when the American Library Assn. selected “This Body I Wore” for its Notable Books List.

When my agent called with an offer of a paid speaking gig at an arts club in Arkansas, I thought, That puts me in a red state. With a single pin in a map, the tour began to take shape. I started contacting state library associations (every state has one) to get the word out. I’d traveled to Arkansas, Missouri, Kansas, Virginia, North Carolina and seven other libraries in Iowa before I arrived in Pella in late July. Florida, which leads the U.S. in book bans, was on my calendar for September.

I’d been following the wave of book bans and attacks on libraries, and reading local newspapers online, in addition to legislative bills, court filings and library board minutes. I published an op-ed in the Tampa Bay Times highlighting the most salient feature of the book bans — the fact that a majority of the targeted books, as tracked by PEN America and the ALA, were by and about minorities, particularly Black and LGBTQ people.

I felt uniquely positioned — even qualified — for this tour. The 2023 Notable Books List citation was perfectly timed. The setting of my pre-transition memoir, in the conditions facing the budding trans communities of the late 20th century — when few of us were safe, accepted, employed, afforded medical care or visible in the media and libraries — also spoke to the current moment. Red-state legislatures were (and still are) trying to reverse decades of progress for trans freedom. (ABC News reports the ACLU recorded “at least” 508 anti-LGBTQ bills introduced in 2023; 84 of them passed.)

The other thing that qualified me were my years as a New York City public school teacher and a touring poet, experiences that trained me to be compelling and relevant in a hurry. And six years of teaching in a juvenile jail in the South Bronx knocked out any stage fright I could feel in front of a group.

For safety, I decided on two rules: 1) Never post my itinerary online; and 2) Never stay in a town where I’m presenting. The thing that concerned me most (a concern shared by several librarians I spoke to) was the possibility of a book vigilante from a surrounding county or state strapping on a gun and getting behind the wheel.

As it turns out, these precautions, for the most part, weren’t needed. My invitations came from libraries that were supported by communities and library boards overwhelmingly in favor of the freedom to read. These tended to be in larger cities, such as Springfield, Mo., or Davenport, Iowa, or in college towns, like Grinnell, Iowa, or Chapel Hill, N.C. Other than in Pella, small-town libraries under threat didn’t invite me.

Of course, nothing prevented me from turning off the road and walking, unannounced, into any library. Had I not done so, I wouldn’t have learned half as much.

:::

The Eureka Springs Public Library, uphill from the center of a historic Arkansas mountain town, was empty except for two assistant librarians behind the reference desk. I asked if they were getting many book challenges. They told me they weren’t allowed to talk about the subject. One of them took out a printed paragraph and read it aloud: “Our library is a plaintiff in a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of Act 372,” she began. Act 372, a law criminalizing librarians and booksellers for “furnishing a harmful item to a minor,” was signed by Gov. Sarah Huckabee Sanders, and was set to take effect Aug. 1, 2023, but is under court challenge. After one assistant librarian finished reading, the other one said, “I hate politics.”

I walked into a good-sized library in a town in the Missouri Ozarks, asked to speak to a librarian and was pointed to a nervous blond woman who looked to be in her 30s. She knew a couple of things about me right away: that I’m trans, and that I’m an author. She knew this because I used my ALA-approved book as a calling card whenever I walked into a library.

Before I could ask my standard opening question of librarians — “Do you feel safe?” — the librarian had something she wanted me to know: “I don’t care if a person is rich or poor or homeless, Black or white or gay or whatever. I’m here to help everybody.” That declaration, akin to the postman’s creed, is something any librarian would say. The odd thing was where she chose to declare it — in the office behind the circulation desk, where she brought me to speak in private.

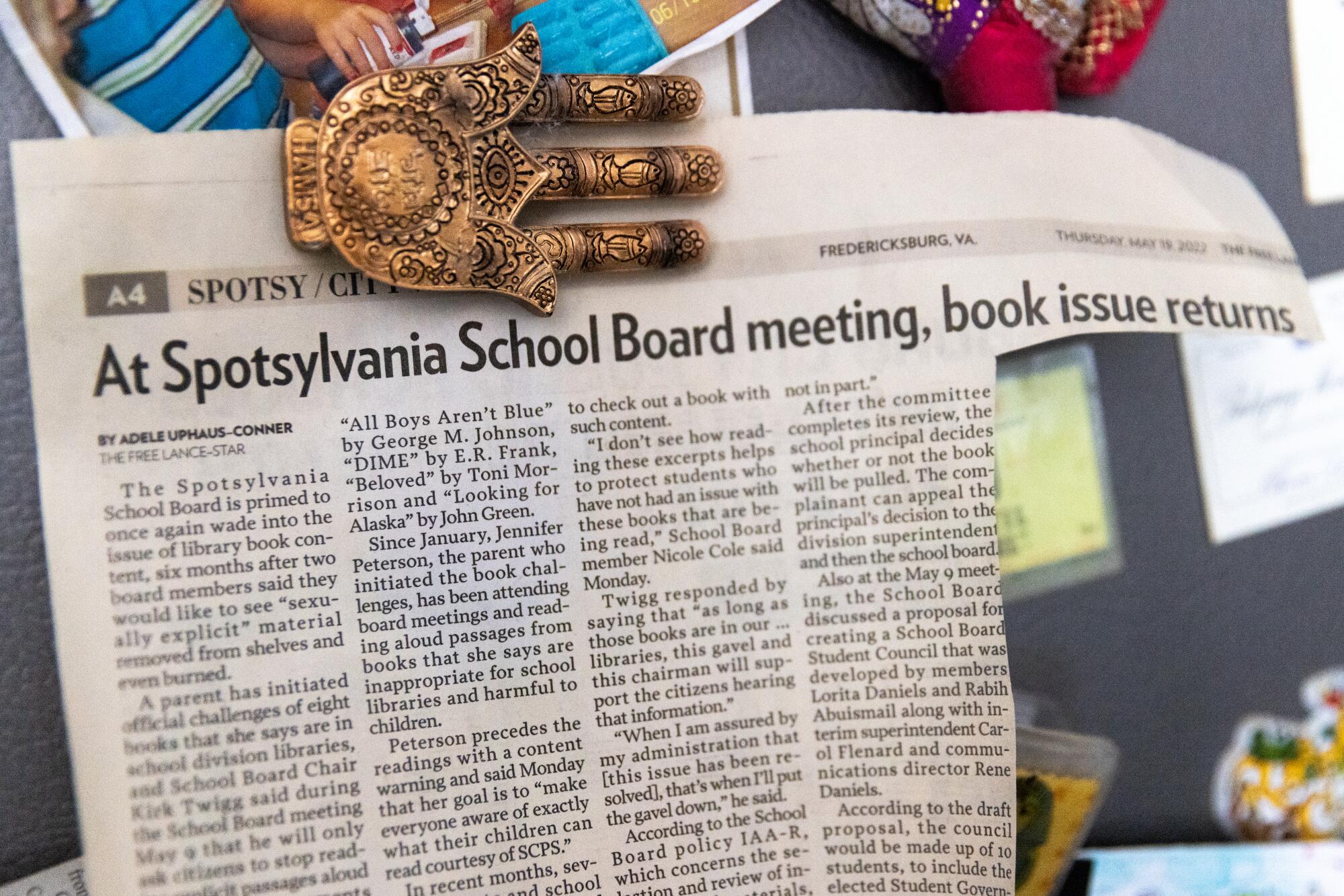

At the Salem Church Branch of the Central Rappahannock Regional Library in Spotsylvania, Va., I spoke with a librarian named Dinah King. In 2021, King was an elementary school librarian in the Spotsylvania school district, where the school board voted unanimously to ban 14 books. Two of the members called for burning them. Soon after, someone created a Facebook “Book Burning event” page, exhorting parents to get their kids to remove “books you do NOT want in our schools,” and bring them to a spot across the street from Riverbend High School, where the school board met.

King doubted the Facebook mob would follow through with their plan (they didn’t — the police showed up in force). What upset her far more was being forced to pull every book from her elementary school library’s shelves to check for “inappropriate” content according to some nebulous definition. One day a fourth grader appeared in front of her with a book about gay civil rights leader Harvey Milk and parroted the line, “This book is an abomination.”

:::

Before heading to Pella, I connected with veteran Iowa journalist Robert Leonard, who was described by the Des Moines Register as a “Trumpland translator” and had been covering a string of disturbing anti-trans incidents in the area. He’d recently reported on a proposal that would effectively ban trans people from an outdoor farmers market in Pella.

Leonard and I met for an interview in a study room in the library on the day of my event. Librarians there, he told me, “are afraid for their safety, for their funding, for their staff, because a small minority of people want to ... erase a group of people off the face of the Earth.”

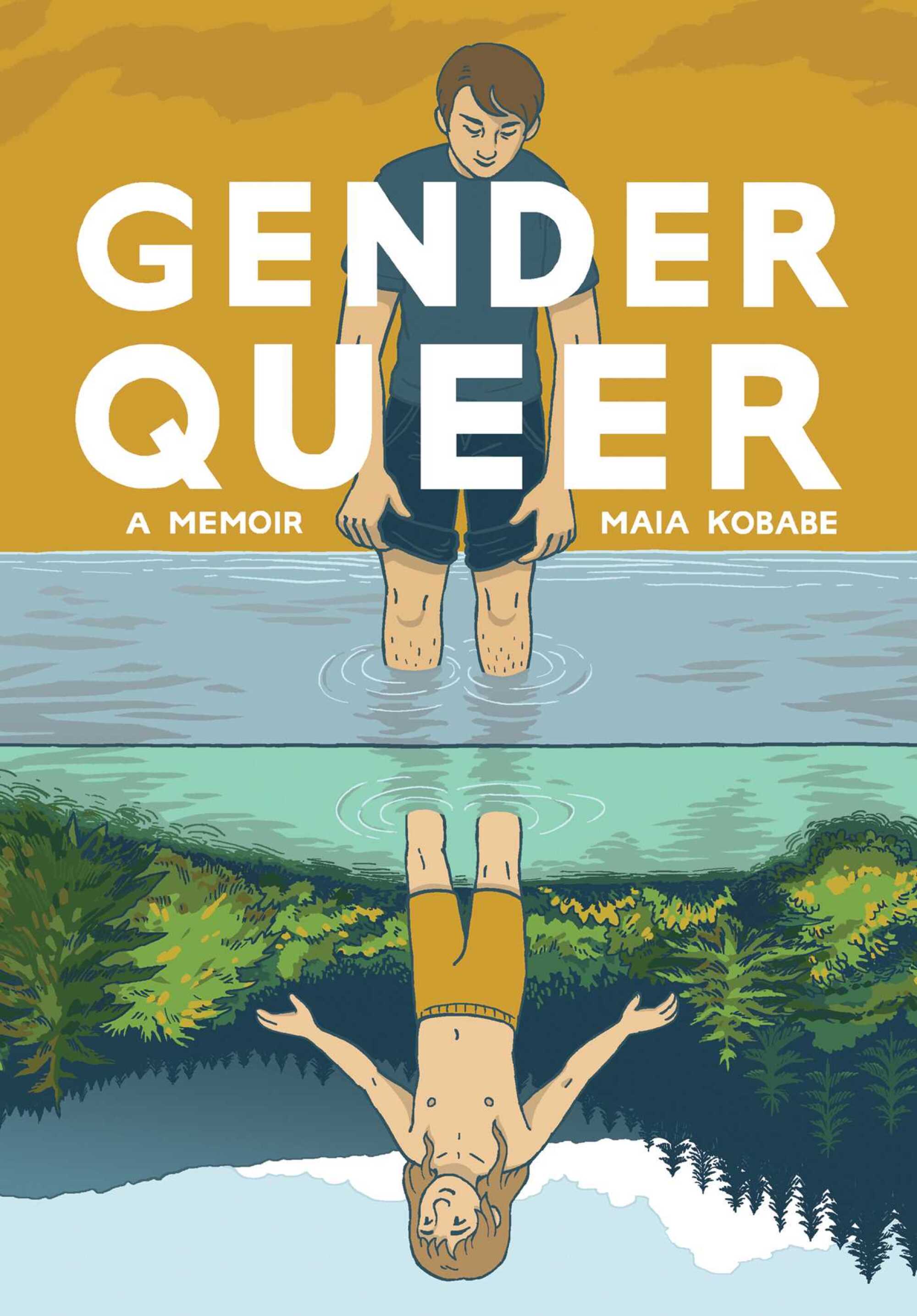

Late in 2022, some townspeople tried to ban the award-winning graphic novel “Gender Queer” from the public library. They also wanted to inspect every book. The library board was having none of it, though there was a push for a ballot resolution that would give the city council control of the library.

In our interview, Leonard and I discussed my red-state tour and why I was doing it. I described what I saw as two layers to the book bans: politically connected groups such as Moms for Liberty spreading propaganda about “protecting children” and a MAGA base genuinely believing the propaganda. I was trying to reach a third group, the so-called movable middle who might be listening to what are considered neutral sources of journalism — and were being told the book bans are part of a culture war.

“It is not a culture war,” I said to Leonard.

“Now [that’s] just pretty amazing to me,” he said, stopping to register what he called an epiphany. “Just that statement — ‘It’s not a culture war’ — sort of reimagines my relationship with the media and my writing.”

Really? Surely he knew the difference between a political wedge issue and ethnic extermination, so why was this an “epiphany”? Maybe it’s because his colleagues throughout the media — at the very outlets that reported doxxing, smear campaigns and death threats to librarians — persist in misframing the crusade as “a culture war.” This includes sources and commentators across the political spectrum — not just the New York Post and Fox News but also PBS, NPR, the New York Times, the Associated Press and Reuters.

It’s one thing to have a culture war debate about school prayer, or a provocative painting in a museum; it’s quite another to stalk and hunt down library staff, to have Proud Boys descend on a library and terrify parents and children. Some of the methods being used — including threats of bombing, shooting and physical harm, and branding one’s opponents pedophiles — are straight out of the Nazi playbook.

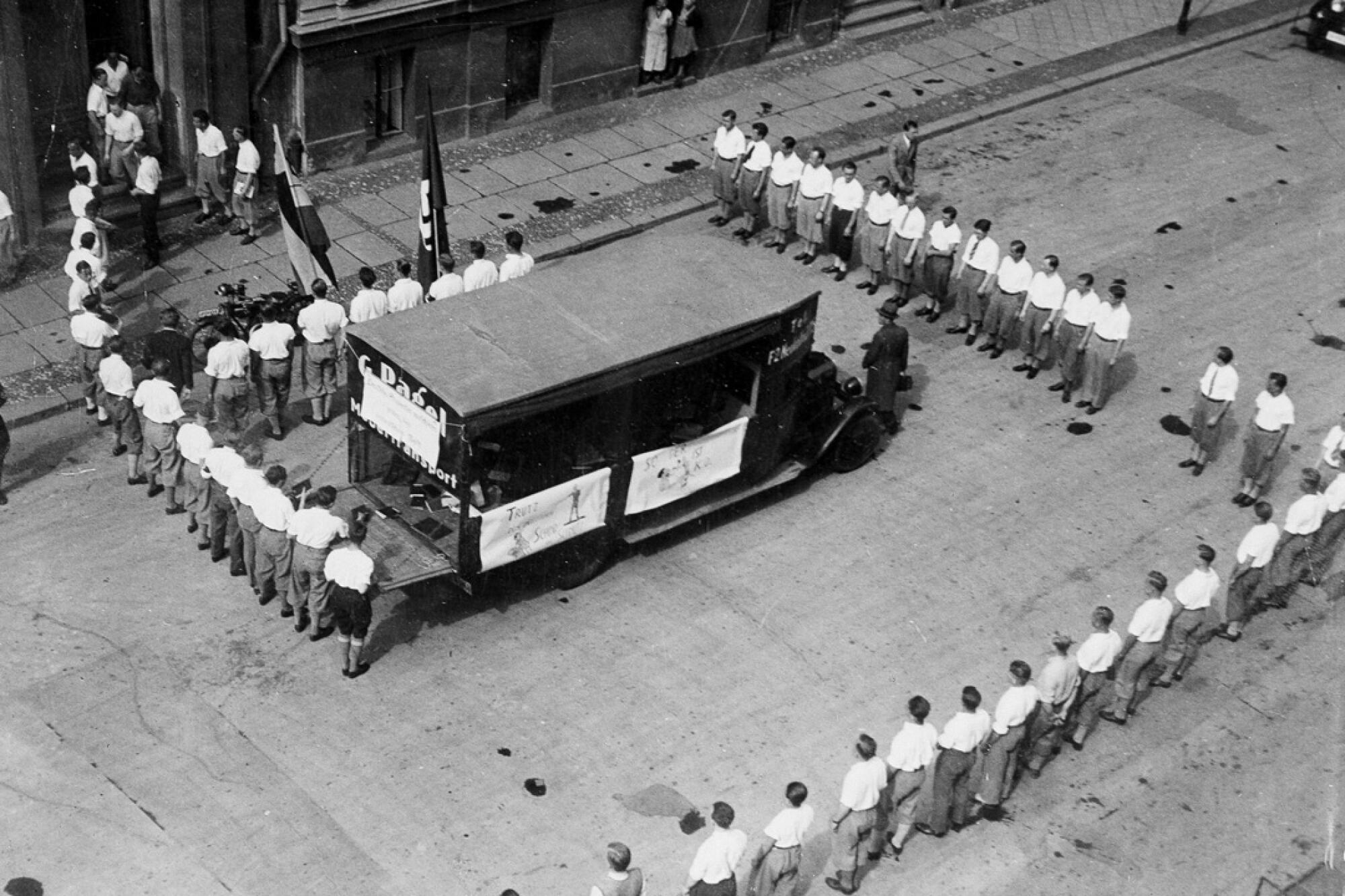

This is why, when I spoke in libraries, I showed footage of the Nazi book burnings. Three months after Hitler came to power there were book burnings in 34 university cities and towns across Germany on the same night — May 10, 1933. But we only ever see newsreel footage of one: the bonfire in the public square outside the Berlin opera house.

As the newsreel played, I explained that the books going into that particular fire were not by Jewish authors; rather, they were burning the 20,000-volume library of a nearby gender clinic, the Institute for Sexual Research, founded by Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld. The library contained the best of what was known in medical and social science pertaining to sex and gender, along with testimonials — memoirs — of LGBTQ people. I wanted people to see the parallels between today and Nazi Germany, where the government was defining many minorities as “un-German” and weaponizing “traditional values.”

When Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels appears, addressing the crowd in that Berlin square, I pointed out something else: While the book burnings were organized by “grassroots” student groups, the Nazi government was fully looped in. It’s not hard to connect the dots to today when I show them the lineup of MAGA elected officials at the Moms for Liberty convention in Philadelphia, or the video clip of them cheering for Hitler — and I never got any pushback.

:::

The crowd for my talk at the Pella Public Library was buzzing in a way I’d never experienced. I introduced my book, and read a passage about the Fabric Factory bar in Times Square and the gender-nonconforming people who gathered there in the late 1980s — “people we were 20 years away from having any respectable words for.” I read a scene from 1977, when I watched Howard Cosell interview Renée Richards on ABC’s “Wide World of Sports,” after she’d won the right to compete in the women’s division of the U.S. Open as a “transsexual.” I was 14 and had never heard that word, or thought such a person could exist, even though I was such a person and somehow knew it.

People were listening; no one was interrupting.

I closed my book and turned to the subject of book bans. I had three points to make: 1) The groups leading the book bans don’t give a damn about protecting children; if they did they’d be talking about assault weapons and smartphones; 2) The groups are highly organized and politically connected; and 3) Their goal, like in Nazi Germany, is to “synchronize culture” with white supremacy.

A man asked why we’re pretending that trans people are something new, when they’ve always existed. I said he had a great point and asked if he knew about the “trans panic” murder defense, a legal tactic now banned in 19 states. For decades, criminal defense attorneys argued that when a man discovers someone he’s attracted to is trans, it can induce panic and cause him to murder one of us.

“Politically,” I said, “MAGA Republicans are trying to induce national trans panic.” They are taking advantage of widespread ignorance about trans people. They want the public voting for candidates who promise to prevent us from transitioning or being seen. This is why they panic when someone trans is accepted and normalized, such as “Jeopardy!” champion Amy Schneider, who had grandmas across America rooting for her. They don’t want books dispelling ignorance about us in libraries, and they especially don’t want trans children to assimilate and grow up in their gender.

Someone asked what would help librarians. “This,” I said, indicating the roomful of people who showed up to defend the freedom to read.

“Having traveled around, what advice would you give to librarians?”

“Advice? I don’t know. They know their situations better than I do. I would just tell them they’re heroes.”

Afterward Mara Strickler and I shared a hug. The gift she had for me was an assortment of fruit-tinged local beers. I poured a can for myself when I got back to my motel room — 30 miles away in Colfax, Iowa.

:::

The goal of My Red-State Library Tour was to defend an institution I loved and to send the message that the book bans are a fascist-style campaign of cultural erasure, which our media has failed to grasp. I don’t know if I succeeded, though I would love for there to be copycats — other authors who travel to libraries to speak, repaying the favors they do for us.

But maybe the main thing I accomplished was simpler than any of that. On election night in 2016, when Florida was called for Donald Trump, I felt, instantly, my country get narrower. I would watch a growing number of trans refugees flee red states, give up their homes and often their jobs, to protect themselves or their kids. My tour was an affirmation, to myself as much as anyone else, that my body belongs in every state of this country. All of ours do, and our books belong in libraries.

Last year on election day, Moms for Liberty candidates were “annihilated” by members of actual parents’ rights groups. My eyes, however, were fixed on a town in southern Iowa and “Resolution No. 6442” — a measure to allow political officials to control the library in Pella, which went for Trump by 68% in 2020. That resolution was voted down, and a great institution remains independent. The vote was close: 51% to 49%, a difference of 87 people. I’d like to think some of those 87 were in the room when I spoke there.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.