So many languages, so few books: Libraries struggle to reflect places they serve

- Share via

Jennifer Songster roved the crowded aisles of the small mom-and-pop shop, riffling through books in Khmer, the official language of Cambodia. Outside, the streets of Phnom Penh bustled. The air was thick and humid. Beads of sweat trickled down her face.

She hadn’t flown for 20 hours to marvel at Angkor Wat, the largest religious monument in the world, or stroll the white-sand beaches of Sihanoukville. Instead, she spent eight sweltering days in the Cambodian capital on a five-figure shopping trip.

Songster works at the Mark Twain Branch of the Long Beach Public Library, home to one of the largest public library collections of Khmer (pronounced Ka-mai) books in the United States. She and fellow librarian Christina Nhek had traveled more than 8,000 miles on a mission that faces libraries across the country: to serve the readers of rapidly changing cities.

The task is neither cheap nor easy. But it is crucial, particularly in Southern California — home to burgeoning immigrant populations who speak scores of languages and have information needs that range from simple to sophisticated.

Songster scouted for books in more than a dozen shops. She juggled dollars and brightly colored riel at tiny cash-only operations. She wandered the aisles of the sprawling Cambodia Book Fair. By the end of her foray, she had shipped home 950 pounds of books, 75 CDs of Cambodian music, 14 posters and three wooden puzzles of the stout, curvaceous Khmer alphabet. The price tag? More than $14,000.

“We need to have materials they want,” Songster said, as she recounted the journey the pair took 13 months ago. Cambodians are “a part of our community. ... The library is there to serve the community, and so it needs to reflect it.”

Few systems send their librarians as far afield as Long Beach has, although Los Angeles Public Library staff members regularly travel to the Feria Internacional del Libro de Buenos Aires, LIBER Barcelona and Feria Internacional del Libro de Guadalajara — the second-largest book fair in the world after the Frankfurter Buchmesse.

Libraries throughout the country especially struggle to broaden collections for their youngest readers. Children’s librarians constantly hunt for books with diverse languages and characters — not just rosy-cheeked, English-speaking, blond girls and boys with straight, married parents.

At the Madison Public Library in Wisconsin, for example, librarian Beth McIntyre vowed to spend the entire easy-reader budget “on books with nonwhite characters and with no animals.” But it was a struggle to use up that money, because “there just wasn’t enough published.” That, she said, is a real problem.

“Literacy depends on children’s desire to read,” said Loida Garcia-Febo, past president of the American Library Assn. “They must have access and be aware that books reflect their culture and language. … [But] the percentage of the children’s books released each year by a person of color or on a multicultural theme has remained unchanged for 20 years.”

This matters now more than ever, because the United States — and Los Angeles County in particular — has changed dramatically.

In 1980, 65% of Los Angeles County residents spoke English at home; by 2018, the most recent data available, that slice of the population had dropped to 41%. Over the same time frame, the percentage of Spanish speakers rose from 21% to 37%.

The top 10 languages spoken in the county also shifted between 1980 and 2018. Nos. 1 through 4 remained the same: English, Spanish, Chinese, Tagalog. But Nos. 7 through 10 changed from German, Italian, Armenian and French to Hindi, Farsi, Vietnamese and Japanese.

Armenian rose from No. 9 to No. 6, which L.A. City Librarian John Szabo said is reflected in LAPL operations.

“When you think about the Armenian population,” Szabo said, “you think of Little Armenia in East Hollywood, you think of Glendale. ... But Sunland-Tujunga has a growing Armenian population. And so we have an Armenian-speaking staff member, at least one, there, and we have [an Armenian language] collection there.”

But being aware of demographic shifts is just the first step when operating libraries in the U.S. county with the largest Latino, Asian and Iranian populations. Understanding the differences within those communities is equally important.

“It’s not just about, ‘Oh, there’s a Latino population within this neighborhood, therefore, we have to have lots of Spanish-language books,’” Szabo said. “In one neighborhood, it might be a third-, fourth-, fifth-generation Latino community. Whereas, in another community there might be many more newer immigrants, where it’s important to have the materials in Spanish.”

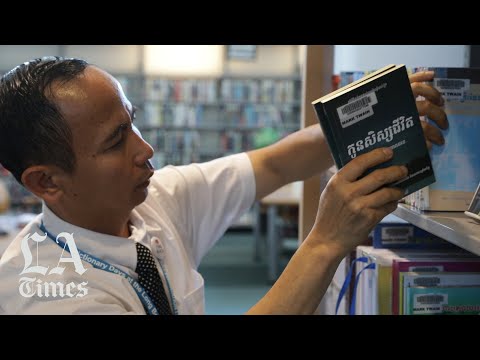

The interior of the angular, orange-and-yellow Mark Twain Branch is a quieter, more orderly version of the neighborhood it calls home: Cambodia Town in Long Beach. Free-standing bookcases of volumes in Khmer line up neatly in front of the library’s Spanish-language collection.

Outside on busy Anaheim Street, the Mekong Center, home to Little Phnom Penh Jewelry, is hard by La Bodega #4. Homeless people push carts holding all their earthly possessions.

With 467,000 residents, Long Beach is California’s seventh-biggest city. More than 10% of the population is of Cambodian descent, the largest concentration of Cambodians outside of their home country.

In the 1950s and ’60s, students from Cambodia arrived in Long Beach as part of an exchange program; many settled permanently. The population boomed after the 1970s “killing fields,” a campaign of terror and genocide by the Khmer Rouge that left nearly 2 million Cambodians dead and forced thousands to seek refuge in the United States.

Since it first opened in 2007, the Mark Twain Branch has made great strides toward serving the city’s Cambodian population. Songster and Nhek survey the community to figure out what its members want to read. Nhek grew up speaking Khmer and is one of two branch staffers fluent in the Southeast Asian language.

But Khmer materials are hard to come by — which is what sent the two women on an international book hunt. Today, in the Cambodia Town branch, about 5,000 of the library’s 63,000 books are in Khmer, more than any language other than English.

“At our professional conferences, like the California and American library associations, you go to the exhibit hall and talk to the vendors,” said branch library services manager Cathy De Leon. “And every time I’d ask the vendors, ‘Do you have Khmer?’ they’d be like, ‘Nope. Can’t get it.’

“We couldn’t get anyone to get those materials for us,” she added, “so the best solution is to go out and get them ourselves.”

Chandara So, who moved to Long Beach from Cambodia in 2019 with his wife and baby, said he’s impressed by Mark Twain’s growing collection, its weekly storytelling sessions in Khmer and how the branch offers American-born Cambodians a glimpse into their culture.

“They learn a lot about their country,” So said, “and about their motherland.”

This fiscal year, Peggy Murphy will spend $16.2 million buying new materials for the 73-branch Los Angeles Public Library system: traditional books, audio books, e-books, comic books, electronic databases and magazines, among other items.

Murphy is the collection services manager, and she oversees a vast system that actively purchases materials in English and a dozen or so other languages.

“Our goal is to become the nationwide, premier Spanish-language collection in the country,” she said. “And when somebody wants to know something about a Spanish collection, they’re going to took at the Los Angeles Public Library and say, ‘That’s the truth.’”

Stocking the shelves of city libraries from Sylmar to San Pedro is an intricate process. The system as a whole buys books from vendors and book fairs for distribution to branches that want them. Branch librarians survey their clients and order books that interest their vastly different communities.

There are official selectors responsible for developing the system’s collection in non-English languages — for Chinese and Japanese and Korean, for Farsi and Russian and Thai, nearly a dozen in all. Spanish has four selectors.

“We don’t just decide that, OK, this branch needs Farsi, and so we buy Farsi without even taking the temperature of the branch,” Murphy said. “That’s why the selectors keep in contact with the branches. ... We take the temperature of the whole system, and we really try to see, is there an increase, is there a decrease, is there a new language coming in?”

Selectors are people like Lupie Leyva, a born-and-bred, code-switching Angeleno with wavy brown hair, Hello Kitty tennis shoes and a gold Virgen de Guadalupe necklace.

Leyva has managed the Robert Louis Stevenson Branch of the city library system since 2011, and she attends the Guadalajara book festival each year. Her Boyle Heights branch is decorated with Mexican folk art. A blue “Citizenship Wall of Fame” honors library patrons who were lawful permanent residents in this predominantly Latino and strongly immigrant neighborhood who have become U.S. citizens.

Most of Boyle Heights’ residents hail from or have roots in Mexico, which is an important consideration when buying books, because there are differences in vocabulary, culture and interests among Spanish-speaking countries.

“The Spanish that’s spoken here tends to be more Mexican,” Leyva said. “In the past we used to rely a lot more on things published in Spain, but now we’re lucky that there’s a lot more in Latin American publishing.”

Self-help volumes published in Mexico are popular with Leyva’s patrons. Most popular teen and children’s books in Spanish, however, are translations, such as Robert Beatty’s “Serafina,” a series about a girl who lives a secret life in a basement, and Ezra Jack Keats’ “The Snowy Day,” a picture book about a black child who wanders his neighborhood after the first snowfall.

Leyva has seen a resurgence in Latino and non-Latino parents wanting their children to be bilingual readers, and “that’s brought up more of a demand for books in Spanish.” Since Proposition 58 passed in 2016, repealing restrictions on bilingual education, she’s lost track of the city’s dual immersion programs.

On an afternoon in September, about 10 excited, chatty students from Euclid Avenue Elementary School’s Spanish-language Book Club met at the Benjamin Franklin Branch to discuss “Sonrie,” the Spanish translation of Raina Telgemeier’s autobiographical graphic novel “Smile,” about life from middle to high school.

Vanessa Vazquez, a former program and policy development specialist for the Los Angeles Unified School District, asked them in Spanish to tell her what happens in the story.

“Alguien fainted,” said a soft-spoken girl. “Someone fainted.”

Vazquez, in a Natalia Lafourcade T-shirt and jeans, red lipstick and multicolored huaraches, struggled to remember the Spanish word for “fainted.” A student came to the rescue.

“Desmayo,” he said. “Gracias,” she responded.

For 10-year-old Pablo Hernandez, reading in Spanish isn’t all that hard; he’s a native speaker, after all. Sometimes he gets stuck on long words “that are new from fifth grade.” But he has his eyes on the LAUSD Pathway to Biliteracy Award, given to fifth- and eighth-grade students who demonstrate excellence in English and another language.

His mother, Juana Guerra, said having her twin sons in the book club has helped their bilingualism evolve.

“They’re learning to speak more clearly in Spanish and are focused on having a bilingual future,” Guerra said in Spanish. Reading the language “is necessary to be a professional, to understand and converse with people who speak Spanish.”

Times staff writer Ryan Menezes contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.