Summary of findings: What can go wrong when firms harvest bodies before autopsies

- Share via

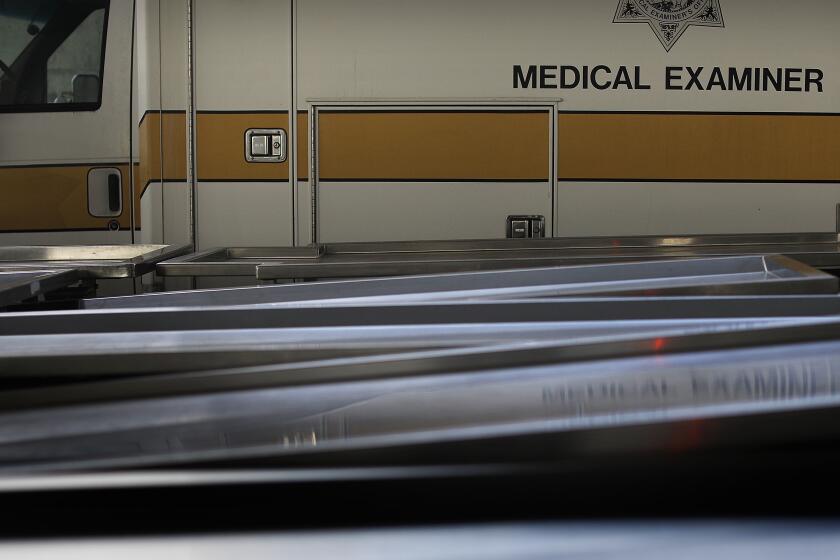

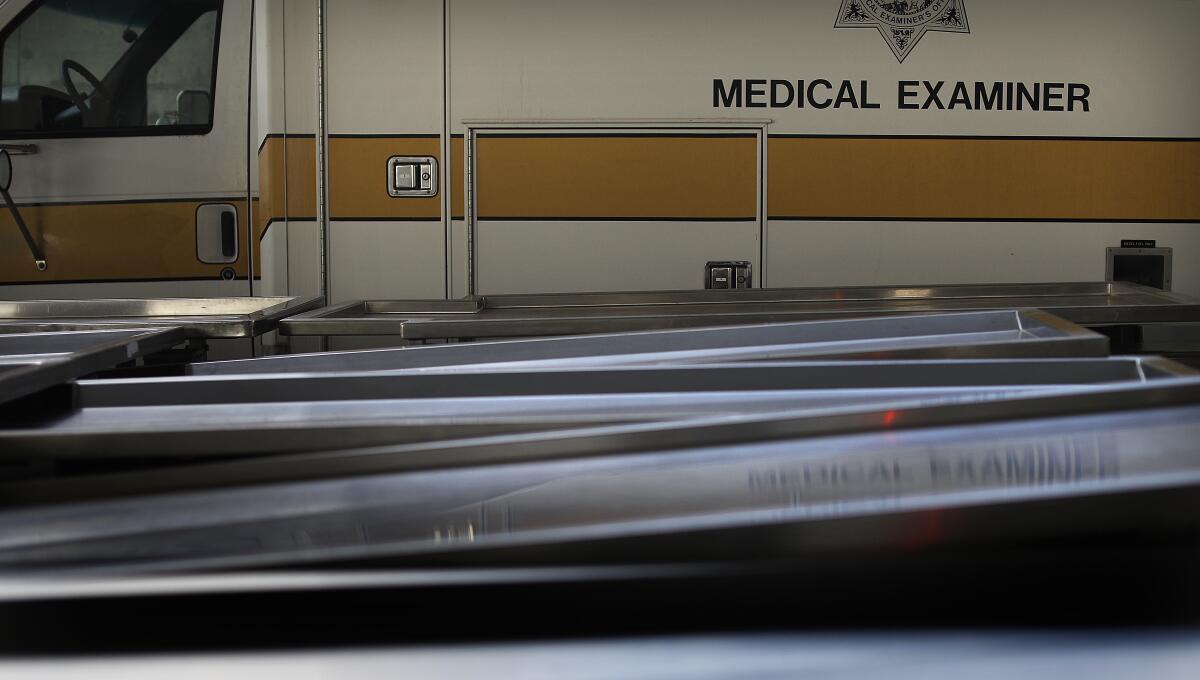

Companies that harvest human organs, bones and other parts have worked their way into government morgues across the country to gain access to more bodies. The companies’ procurement teams often are taking body parts before coroners are able to conduct an autopsy, even in the midst of sensitive investigations such as possible homicides.

The procurement companies say there has never been a case in which a death investigation has been harmed by the procurement of body parts. Yet The Times found more than two dozen such cases in just two Southern California morgues. Reporters found nearly as many other cases across the country.

At least one murder prosecution has been dropped, civil lawsuits have been thwarted and families have been left without answers of why their loved ones died. At times, investigators could not look for abuse or violent injuries because bones and skin were already gone. A possible police-involved death remains unsolved.

Here are some other key findings:

An industry shaped a law

The number of flawed investigations has increased after the industry that trades in human body parts helped write legislation that required coroners to “cooperate” with the companies to “maximize” the numbers of organs and tissues harvested for transplant. The companies’ lobbyists then helped push the legislation into law in many states.

The new laws made it harder, and in some states, impossible for coroners to stop the procurement of body parts if they believed it would harm their investigation.

To pass the laws, the companies’ lobbyists pointed to published research papers that concluded body parts could be taken before the coroner’s autopsy with no harm to the death investigation. The Times found the papers were co-written by industry executives and others with ties to the companies.

Medical examiners and coroners were outraged in 2007 when the procurement companies helped write the laws. The forensic officials said they had been shut out of discussions where the legislation was drafted. Since then, the procurement companies have tried to soothe that anger. The companies are now among the biggest funders of gatherings of the nation’s death investigators, often paying for cocktails, dinners and rounds of golf.

It’s not just about lifesaving organs

The procurement companies said the laws were needed to increase the number of organs available for patients waiting for transplants. Yet it has done far more to grow the amount of bone, skin, fat and other human parts sold by the biotech industry, including for cosmetic fixes.

The sale of Americans’ body parts around the globe is now a multibillion-dollar business, in which less than half a teaspoon of ground skin can fetch $434. That product and more are used by cosmetic surgeons to plump lips, cheeks and other parts.

You may not get to decide

Even if you have not signed up to be a donor, the companies can harvest your parts when you die if they can persuade your grieving family to allow it.

When you die, a procurement company will be quickly notified. Hospitals must report every death to the companies for possible harvesting. Many companies now also know immediately about deaths outside of hospitals through connections to government computers in county morgues. At times, the companies have contacted families, asking them to agree to procurement, while the body is still at the death scene.

Some families say they feel the companies misled them into agreeing to procurements. Some say they were not told the donation of organs or tissues could harm the coroner’s ability to determine the cause of death.

Coroners rely on the companies

Coroners are increasingly dependent on the companies’ procurement teams to document injuries from violence or accidents even though the employees have little professional training in forensic science.

The companies have 24-hour access to many county morgues, raising questions about whether evidence could be tainted.

The Times found several suspicious deaths that may have been caused by violence or accidents that were not reported to coroners by procurement companies or the hospitals working with them. Failure to report such deaths is illegal under California law. It’s impossible to know how many other unnatural deaths may have never been reported.

Some procurement companies have tried to keep their work in the county morgues secret. Several worked with coroners in at least two California counties to try to keep The Times from reviewing how procurements were affecting coroner autopsies. Reporters instead combed through death records previously obtained from the coroners to find and review cases in which body parts were harvested.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.