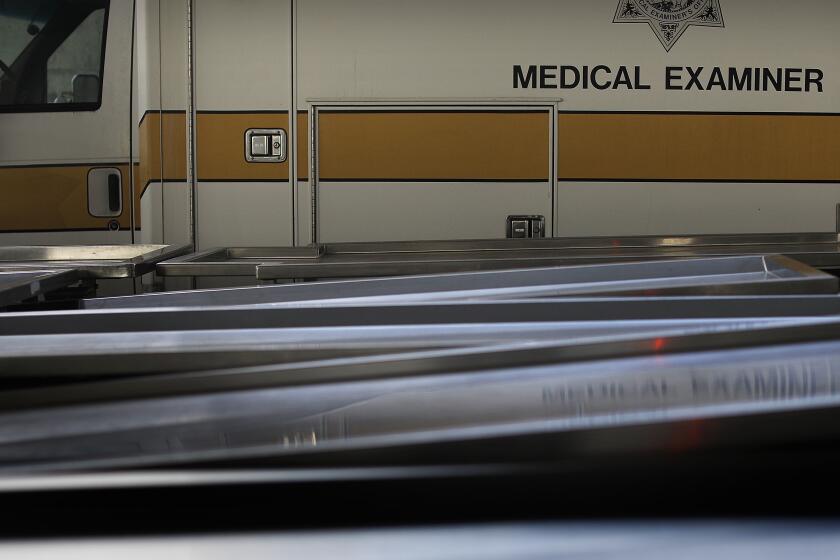

When someone dies unexpectedly, responsibility for determining the cause falls to the coroner, according to California law. At a minimum, the coroner must view the body to ensure there’s no sign of trauma or foul play, according to rules on the L.A. County coroner’s website. When some young and middle-aged adults died suddenly, however, companies harvested bone and skin even before the coroner could view the body. OneLegacy, which procured the tissue in some of these cases, told The Times the coroner often allowed it to procure tissues if a death was believed to be from natural causes. The coroner’s office said as a safeguard in those cases it had instructed OneLegacy not to remove fractured bones.

Jesse Meza was just 33 when his mother couldn’t wake him in the early morning of June 23, 2009. Paramedics pronounced him dead at their South Gate home. A coroner’s investigator viewed his body at the funeral home a week later, finding that bones and patches of skin were already gone. “No obvious signs of trauma were observed, however previous harvesting prevented any meaningful examination,” the investigator wrote.

Diane Smith, 49, was in cardiac arrest when she arrived at Lakewood Regional Medical Center on March 27, 2009. About a week later, an investigator from the coroner’s office examined the body of the Inglewood resident, finding that skin and bones had been procured. “Body was viewed at the [mortuary] after harvesting therefore, preventing any meaningful examination,” the investigator wrote.

An investigator from the L.A. County coroner’s office arrived at a Long Beach mortuary in December 2007 to find the body of Edita Pickel, 66, in “poor condition,” according to a coroner’s report. “The body appeared to have been harvested for skin and is therefore not possible to check for any obvious signs of trauma,” the investigator wrote.

An emergency crew pronounced Heidi Ann Nelson, 62, dead when they arrived at her Long Beach home in November 2008. She had not been breathing when her husband found her. A week later, an investigator from the coroner’s office examined Nelson’s body at the funeral home. “Obvious signs of harvesting … prevented observation of any signs of trauma,” the investigator wrote.

Raymon Clary, 65, of Anaheim passed away in 2009 in the emergency room of Glendale Adventist Medical Center. A coroner’s investigator examined his body at the funeral home, finding incisions down the length of both arms and legs. Another surgical cut crossed his abdomen. “Further examination of the body was not practical as harvesting had occurred,” the investigator wrote.

Oscar Ashford, 52, of Torrance was found in bed not breathing. A doctor at Little Company of Mary Hospital pronounced him dead in the early morning of May 26, 2009. His unexpected death was a mystery. He had no known history of drugs or alcohol. A coroner’s investigator viewed his body at the funeral home a couple of days later. “Body was … in poor condition due to harvesting on both the back and front of the body,” the investigator wrote.

Kenneth Flynn, 56, of Azusa was vomiting and having trouble breathing when he arrived at Foothill Presbyterian Hospital on July 6, 2009. A coroner’s investigator viewed his body at the funeral home, finding surgical incisions down his arms and legs. Patches of skin were gone from his legs, arms and back. “The decedent has been harvested prior to being examined by our office,” she wrote.