- Share via

TAIPEI, Taiwan — In a pivotal scene from the hit Taiwanese drama “Wave Makers,” senior political staffer Weng Wen-fang crouches outside a rollicking karaoke room, making a drunken call to another woman on her team, Chang Ya-ching.

Chang had been sexually harassed by a male colleague but, assuming futility, declined to file a complaint. On the phone, Weng urges Chang to not brush it off, and promises to stand firmly by her younger co-worker.

“Let’s not just forget this, OK?” Weng says. “So many things can’t just be forgotten like this. If they are, people will slowly die. They’ll die.”

At those words, Chang starts to cry.

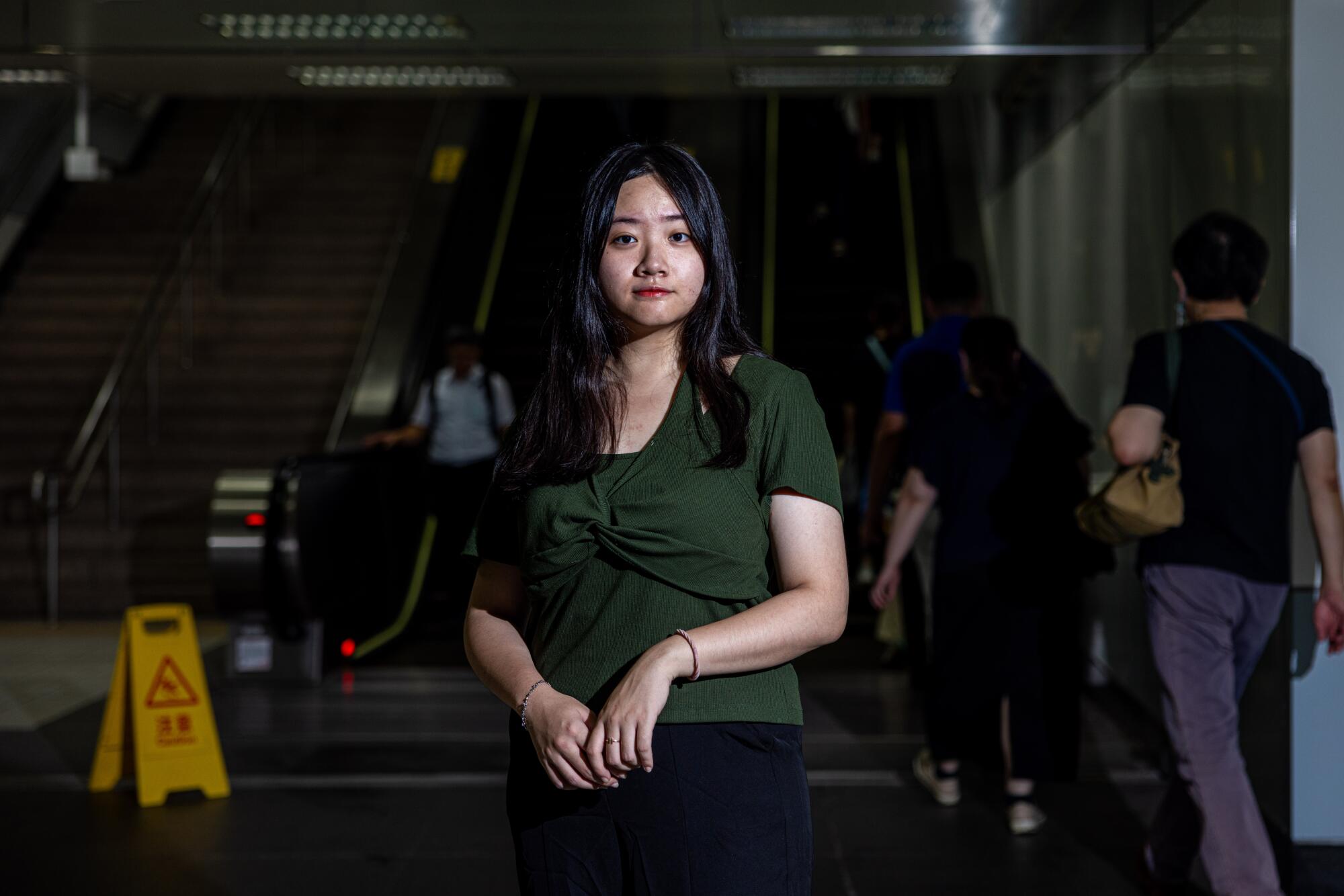

Watching the smash Netflix show at home in May, 22-year-old Chen Chien-jou burst into tears too. For weeks she had been a zombie, trying unsuccessfully to process her own experience of reporting harassment while working as a campaign staffer for Taiwan’s ruling Democratic Progressive Party.

In September, she said, a film director hired by the DPP had guided her head to his chest and massaged her, touching her close to her breast on a car ride back from a video shoot. Back at the office, she said, he paced outside the bathroom in which she had locked herself, daring to emerge only when she heard other people’s footsteps approaching.

But when she reported the incident, Chen said her manager responded by asking: “So what do you want me to do about it?” Chen quit working for the DPP in April. She was also seeing a psychologist, and taking medication to help her sleep.

A new Taiwanese Netflix drama envisions a world of politics with women at the forefront — and tensions with mainland China conspicuously absent.

It was then that she tuned into “Wave Makers,” unaware that it would unleash a wave of emotions within her — and a #MeToo-style reckoning that for the last two months has swept through the worlds of Taiwanese politics, entertainment, academia and civil society, years after similar movements elsewhere.

On May 31, quoting Weng’s words from the show, Chen published her account on Facebook before going to bed. By morning, her story had gone viral. Before the day was out, both Taiwan’s president and the DPP’s candidate for the January presidential election publicly apologized for what she went through. Her former supervisor resigned, and the DPP ended its relationship with the film director, who apologized for touching Chen’s head and neck but denies caressing or massaging her.

“Real life doesn’t have as good of an ending as on TV,” Chen told the Los Angeles Times in an interview. “But today I have a chance to change that.”

Since her groundbreaking post, hundreds more from others have followed. The outpouring has led to further resignations, lawsuits, rebuttals and a broader discussion of how one of the most progressive societies in Asia confronts sexual harassment and assault — or, rather, has largely failed to.

Whereas U.S. courts started hearing sexual harassment cases in the 1970s, Taiwan didn’t define it as a specific crime until 2005. The self-governing island, which languished under martial law until 1987, didn’t even have a statute on sexual assault until 1997, after the notorious rape and killing of feminist activist and politician Peng Wan-ru.

Cultural norms have also kept victims from speaking out. A 2021 annual survey by the Taiwanese Ministry of Labor showed that 79% of women who said they were sexually harassed at work chose to not report it, partly out of concern over being maligned or losing their jobs. Swallowing such encounters in silence is known colloquially as chi doufu, or “eating tofu.”

Indigenous Taiwanese want to abandon their Chinese names, giving rise to a politically charged debate amid rising cross-strait tensions.

Chang Tao-wen, 47, said when she was sexually harassed in 2011, she thought it would be easiest to keep quiet. But hearing another woman share a similar experience spurred the professional cellist to come forward with her own story last month.

She said that internationally known violinist Lin Cho-liang had invited her to his hotel room, ostensibly to discuss performance opportunities, but then asked to touch her breast and massaged her feet and back. She said she pretended to receive a call from her mother in order to politely leave.

A law firm hired by Lin said in a statement that the accusations were baseless. In a Facebook post, Lin said he never tried to make anyone uncomfortable and apologized if he had.

The cellist said that at the time, her boyfriend had wanted to report Lin. But she assumed she lacked the necessary evidence, and her mother was fearful of the possible backlash.

“From the time we were young, I never learned how to protect myself or how to say, ‘Stop, please don’t do that,’” she said. “I had other options — I just didn’t know. I think that’s very unfortunate.”

Stories like hers seem to be changing that. The Garden of Hope Foundation, a women’s rights group in Taiwan, said it has received more than 110 calls about sexual harassment since June 1, compared with an average of five or six per month.

Even one of the screenwriters of “Wave Makers,” Chien Li-ying, was encouraged by the movement her show helped create. On June 2, Chien wrote on Facebook that when she was in college, the exiled Chinese poet Bei Ling sexually harassed her after inviting her to his home. Bei denies the allegations, saying he and Chien had a close relationship.

When #MeToo started trending in the U.S. in 2017, writer Wu Pei-shan had hoped it would catch on here too. Just before, she had started an organization called Have You Heard to combat harassment.

But as #MeToo spread to Japan, South Korea and even mainland China, it failed to take root in Taiwan, despite the island’s reputation for progressive attitudes on gender — it was the first place in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage and has had a female president since 2016.

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Wu’s project came to an end in 2019 after criticism that it lacked resources and qualifications to adequately assist victims. But she said she hopes such initiatives helped lay the groundwork for today’s embrace of the issue. Last month, she and several other women made public the stories that had led to the founding of Have You Heard, accusing a Taiwanese academic of sexual harassment. The academic issued a statement on Facebook apologizing to those he had offended and harmed.

“Though this accumulation doesn’t have a name or a big so-called movement, we also have to look at the small everyday people and their small everyday efforts, and know that Taiwanese society has not done nothing these last five years,” Wu, 34, said.

This time around, the debut of “Wave Makers” in April and the show’s enormous popularity primed public consciousness for the explosion of accusations that followed. The fact that the initial claims arose in the political sphere less than a year before a presidential election also put pressure on politicians to address them at once.

“Sometimes our system needs impact from the outside,” said Hsu Kai-chieh, a judge with the Taipei District Court. “If it was just one thing, one small thing, nothing would happen. But if you have a hundred small things, something might.”

Since Russia invaded Ukraine, more Taiwanese say they are willing to fight if attacked by China. But without firearms or sufficient military training, many wonder how to prepare.

The executive branch of Taiwan’s government has now proposed amendments to sexual harassment laws that would include harsher penalties, extend the statute of limitations for complaints and broaden gender equality education.

Another welcome result of the recent movement, academics and accusers say, is that male victims are getting more attention too.

For Lee Yuan-chun, that meant nine years of agonizing over whether to come forward ended with a spur-of-the-moment decision in June.

In the space of half an hour, Lee, 29, wrote and published a Facebook post that accused Wang Dan, a prominent Chinese dissident, of attempting to sexually assault him in 2014.

According to Lee, he met Wang at a democracy symposium in Taiwan in 2013. Wang had come to international renown as one of the leaders of the student-driven pro-democracy protests in Tiananmen Square that the Chinese government brutally crushed in 1989.

In the spring of 2014, Lee said, Wang invited him on a two-week trip to the U.S. On June 6, Lee said Wang forcibly kissed him in a New York hotel room before pushing him onto the bed and taking off his own clothes.

Panicked, Lee said that he was recovering from anal surgery. Wang stopped, but continued to make sexually suggestive remarks, said Lee, who decided to cut his trip short and return to Taiwan.

The alleged incident weighed heavily on Lee every year around June 4, the anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre. In 2015, he wrote a long, cryptic Facebook post that decried the annual commemoration and accused an unnamed person of doing “dirty things,” then typed “Go to hell” more than 100 times.

Even in Boston, China might be watching, these protesters fear. They use fake names, masks and encrypted apps, because even a friend may be a spy.

In 2019, he posted: “I will, I will remember June 4. But now my only, only impression of June 4 is just that the person remembered with it is also the person who almost raped me five years ago, if I had not protested at the time.”

Fear of potential consequences long kept Lee from speaking more plainly. He anticipated personal attacks and fallout in his career. Before June of this year, he had not come out to his parents as gay, and worried the accusations might discomfit his family. He was also reluctant to make public insinuations about Wang’s sexuality.

After Lee published his headline-making Facebook post last month, Wang denied the accusations and suggested that the story could be politically motivated. Angered by his denial, Lee filed a lawsuit against Wang for attempted sexual assault. Contacted by The Times, Wang declined to comment on the suit.

“Everything happened very quickly,” Lee said. “If everyone’s cases were a large wave, I was just a drop of water — a plunk and then gone. I didn’t think it would become this big.”

Taiwan’s nationalist party is looking to the purported great-grandson of Chiang Kai-shek to refurbish its image.

As others’ accusations flooded her Facebook feed throughout June, Chang Ling-lang waited to see whether any of her harassers would be named.

Over the last decade, the 36-year-old livestreamer (who is not related to Chang the cellist) had discovered sexual misconduct to be commonplace in the entertainment industry. Still, she had no plans to make any accusations until she saw Chen Hsuan-yu, a Taiwanese entertainer better known as Nono, say he had no recollection of a woman’s allegation that he sexually assaulted her in his car.

That woman quickly became the target of online attacks. But the story rang familiar to Chang, the livestreamer, who said she remembered her own unpleasant experiences in the famous comedian’s car. One night in 2010, she said, Nono started touching her thigh during a car ride and forcibly kissed her at a red light. She said he then took her to a dark park where he groped her breasts, legs and buttocks.

For 13 years, she said, she stayed silent.Then on June 20, she posted her account on Facebook shortly after midnight. She stayed awake until 10 a.m., shaking with the same fear that had kept her from standing up to him the night of the alleged incident.

The next day, Nono said on Facebook he would cease work and reflect deeply on himself.

Since then, Chang said, more than 30 people have reached out to her with similar stories. She and others have filed a lawsuit against the entertainer for sexual harassment, sexual assault, attempted sexual assault and statutory rape. Nono did not respond to requests for comment on the allegations and lawsuit.

“If he really is convicted, then everyone will know sexual harassment and assault really isn’t a joke,” Chang said. “Maybe our generation won’t be able to change, but it could affect the next generation, my children, my grandchildren, and let everyone know that Taiwan is a place of law.”

Even with Taiwan’s #MeToo movement finally taking off, she said many women she’s connected with are still afraid to speak publicly. Although she’s received hateful messages and threats of violence, Chang said she has no regrets. And in the worst times, she turns to her new friends online for comfort.

“When I’m afraid, I think of them and I’m not afraid anymore. When they are afraid, they think of me and aren’t afraid anymore,” she said. “So we have been brought together.”

Yang is a Times staff writer and Shen a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.