- Share via

On an overcast December afternoon in Boston, 11 Chinese citizens arrived one by one at an underground parking garage — their clandestine meeting spot.

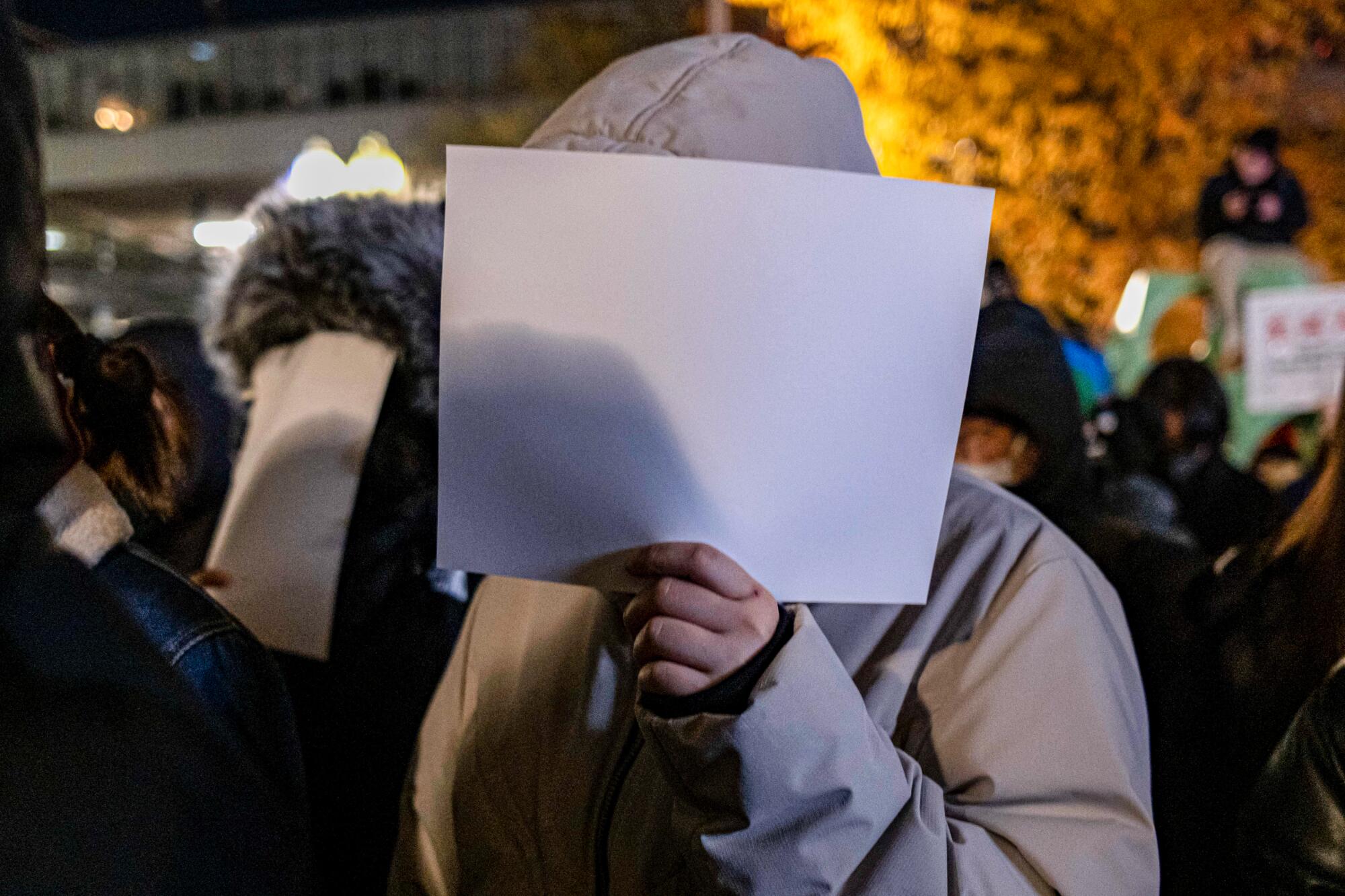

As planned, they wore all black, with hats and masks obscuring their faces. They had hoped their outfits would make them less visible. But the curious looks they drew made them feel like criminals.

That might have been the case if they had tried this in China. They had gathered to demonstrate against the Chinese government, the kind of act that could land them in prison back home.

Even in Boston, 12 time zones away from Beijing, the Chinese Communist Party might be watching. Might be listening. Or so they thought.

They feared the government would retaliate against their relatives in China. They all held green cards or student or work visas — what would happen if they returned home? They worried too about extreme Chinese nationalists in the United States. Would they harass them? Report them to the government?

They even wondered if they could trust one another. Might one of their members be a spy? One couldn’t be too careful.

And so they took safeguards, communicating on the encrypted messaging app Telegram, using security escorts to make sure they weren’t followed at their event and concealing the basic details of their lives — ages, jobs and Chinese hometowns — from one another. Most didn’t even know one another’s names.

After a week of planning, they were now meeting in person for the first time, still using the pseudonyms they adopted online. With an hour to go before the vigil, an organizer who called herself KK handed out walkie-talkies as everyone turned off their phones. Another code-named Roger loaded banners, folding tables and loudspeakers into his SUV.

“I don’t want to connect my real identity with these activities,” recounted an organizer who went by Lucy. “It’s really a known thing that people will report people who are against the government. I can’t risk that.”

::

In October, days before Chinese President Xi Jinping was confirmed for five more years as the head of the Communist Party, a lone protester hung two banners across a Beijing bridge.

One called for a worker strike and Xi’s removal. The other declared, “We want food not COVID tests, reform not Cultural Revolution, freedom not lockdowns, votes not leaders, dignity not lies, to be citizens not slaves.”

The man believed responsible, 48-year-old Peng Lifa, disappeared. But his slogans were soon being scrawled on buildings and anonymously sent to smartphones, a potent refrain for opposing Xi and his draconian zero-COVID policy.

An unprecedented third term will enable the Chinese president to more aggressively pursue his vision for global dominance.

The fervor also spread among Chinese nationals abroad. More than 6,000 miles from Beijing, three friends in Boston were transfixed by the news. They started thinking about how they could show solidarity with Peng and other compatriots back home.

“We were like, ‘We can’t just let this thing go away. We have to do something to honor that man’s bravery,’ ” said Lucy, a software engineer who had left China more than a decade earlier.

Online, her two friends took the names Roger and Ellen. An Instagram account used by Chinese expatriates to organize protests around the world led them to KK, who had started a Telegram channel for activists in Boston.

On a Wednesday night in late October, the four met in a park and painted replicas of the Beijing banners. The next morning before dawn, they reconvened on a highway overpass near Boston University to hang them from the chain-link partition.

The banners were seen from thousands of passing cars before they became tangled in the wind the next day. While Lucy and her friends were retrieving them, a Chinese woman approached. They eyed her nervously, until she confided that the signs had made her feel powerful.

The protesters felt emboldened too. They weren’t exactly new to political demonstrations — they had been to women’s rights marches or Black Lives Matter protests — but directly challenging Xi had broken a major taboo.

They began hanging more protest signs around the city and connecting with other Chinese nationals online. On Halloween, a group of them donned white full-body suits — the uniform of the workers enforcing COVID lockdowns in China — and walked the streets putting up fliers denouncing Xi and the Communist Party.

Back in China, tensions were escalating over the government’s tightening hold on everyday life. Then on Nov. 24 in Urumqi, the capital of the Xinjiang region, 10 people died when a fire broke out in a high-rise apartment building and COVID restrictions prevented residents from leaving and firefighters from entering.

Vigils for the victims turned into protests in Shanghai, Beijing and other cities — the largest mass demonstration against China’s leaders since the 1989 gatherings in Tiananmen Square.

First-time protesters in China grapple with how much agency they can wrest from an authoritarian government after the largest demonstrations since 1989.

As solidarity protests broke out in Los Angeles, New York and elsewhere, somebody started a new Telegram group with the aim of holding a vigil in Boston for the coming Friday, Dec. 2. Soon the group had about 500 members.

Debates in the channel grew heated over what signs to hold, what slogans to chant and whether to condemn China’s oppression of the ethnic minority Uyghur population in Xinjiang. Overwhelmed, Roger, Lucy, Ellen, KK and several others broke off into a new channel, which became the de facto organizing committee to recruit speakers, make signs and reach out to activist organizations.

Stress mounted as the vigil drew closer. When one organizer began pushing the others for personal information, they removed her from the channel.

“Everyone was burned out,” Ellen said. “We didn’t have time to worry about suspecting someone from our group that could be a threat or a security concern.”

When Ellen went to pick up posters she had made at Staples, she spotted a man printing documents who appeared to be Chinese. Fearful of how he might react to her signs accusing the Chinese government of Uyghur genocide, she paced between two aisles of paper boxes for half an hour, peeking in his direction until he left.

The next day — Dec. 2 — she and the other organizers made their way from the parking garage to the Tiananmen Memorial in Chinatown a few blocks away. They propped up their posters, set up speakers and strung one of the banners from the overpass between two trees.

Night fell, and as the crowd grew, so did the memorial of candles and flowers left for the victims of the Urumqi fire, all of them Uyghurs. Soon there were more than 400 people, many as heavily cloaked as the organizers.

Over the next hour, attendees observed a moment of silence for the dead, chanted slogans and sang Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Do You Hear the People Sing?” from the musical “Les Miserables,” a popular song among anti-government demonstrators in Hong Kong in 2019. Speakers took turns at a microphone, most of them hiding their faces.

“I hope that one day we can meet again in the sun without masks,” the moderator, code-named Charlie, told the crowd. But he said later he doesn’t think that will be possible as long as he has family in China.

::

Two weeks after the vigil, a 25-year-old Chinese national in Boston was arrested for stalking a woman who had posted fliers for democracy in China. According to the charging documents, he threatened to cut off her hands and told her he had reported her to Chinese authorities, who would be making a visit to her relatives back home.

Such stories about harassment and rogue informants have sown deep mistrust within the Chinese diaspora, and many find it easiest to stay quiet when it comes to Chinese politics.

That was long the case for Lucy, who before December had few Chinese friends with whom she could criticize the government back home. While she and the others know it’s unlikely their actions will change much in China, working together has eased the isolation that many felt.

“You know that you’re not alone thinking like this; there are others with the same values,” Lucy said. “That just makes me feel like a normal person again.”

The original plan was to disband after the vigil. But the turnout that day convinced them there was value in planning more events.

“We realized that maybe this is a great chance for us to continue doing the work, and not just let this be a one-time thing,” said an organizer who went by Yi.

They’ve since attended other protests together, including a February rally they organized to commemorate Dr. Li Wenliang, who was arrested for warning people about the coronavirus, which later killed him.

For Yangyang Cheng, a researcher at Yale Law School’s Paul Tsai China Center and a Chinese citizen, an anonymous email was sufficient to persuade her to speak at the event. As for why so many other protesters concealed their identities, she said it was an understandable response to the ambiguous nature of fear sown by authoritarian governments.

“It really shows a certain precarity and fragility of being Chinese anywhere,” she said.

Trust has grown considerably among the vigil organizers, who now discuss restaurant recommendations and movies as much as they do politics. Some attended an underground play together about an exiled Chinese dissident. There was also a ski trip to New Hampshire and talk of starting a book club.

Occasionally they meet at Roger’s apartment, since he’s the only one comfortable sharing his address. They’ve made a game out of guessing one another’s jobs and hometowns based on their accents.

Still, when they eat out, they pay one another in cash rather than Venmo, which is linked to their bank accounts.

“We don’t really know each other’s real names or telephone numbers,” said Charlie, the moderator. “But other than that, we really feel like we are friends.”

Times staff writer Yang and special correspondent Shen reported from Taipei, Taiwan.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.