India is using two different COVID-19 vaccines. Uncertainty surrounds one of them

- Share via

MUMBAI, India — As India launches an ambitious effort to vaccinate 300 million people against COVID-19 within six months, it is employing two vaccines — both manufactured domestically but approved under very different circumstances.

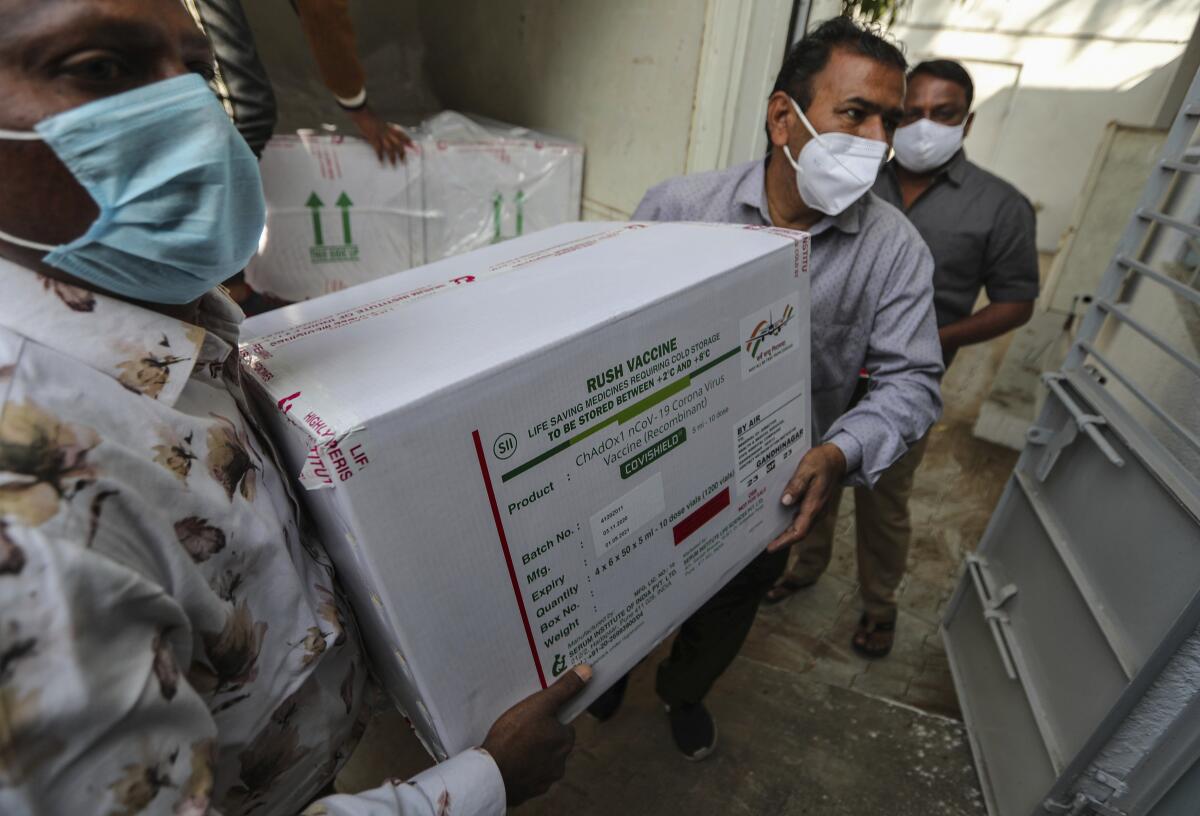

One is Covishield, the vaccine developed by Britain’s AstraZeneca and Oxford University, which clinical trials show is about 70% effective in preventing COVID-19 and is being manufactured in India by the Serum Institute, the country’s largest drugmaker.

The other is Covaxin, developed by an Indian company in conjunction with the government but whose performance in late-stage clinical trials has yet to be published. Health authorities nevertheless authorized the vaccine for “restricted emergency use.”

Government health officials promise that both drugs are effective and say that Indians who line up for the first phase of shots will not be able to choose which drug they receive.

“Many countries across the world are using more than one vaccine,” Health Secretary Rajesh Bhushan told reporters Wednesday. “There is no such option [of choice] available to any of the beneficiaries in these countries.”

Uncertainty over the Covaxin shot is just one challenge facing India as it rolls out one of the biggest vaccination drives in world history.

Beginning Saturday, vaccines will be administered to 30 million medical professionals and front-line workers, followed by an additional 270 million people age 50 and older or those at risk because of other illnesses. Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s pledge to complete the first phase by August would put India, which has the world’s heaviest coronavirus caseload after the United States, on track to defeat COVID-19, experts say.

But the populist Modi is known for bold pronouncements that don’t always materialize. Experts warn that the lack of transparency surrounding Covaxin threatens to undermine public trust in the inoculation drive.

“Whatever has happened, it has created a perception that the vaccines are not the same,” said Prashant Yadav, a senior fellow at the Center for Global Development in Washington who studies India’s healthcare supply chain. “That has the potential of creating delays and more friction in a process which we ideally want to be as smooth as possible.”

A study of 660,000 Indians finds that a few individuals spread most new infections and that children transmit the coronavirus just as well as adults.

Although China and Russia also have begun administering domestically produced vaccines while the drugs are still in the trial phase, India stands out for signing off on two drugs based on different standards.

The AstraZeneca-Oxford shot was approved Jan. 1 by a panel of experts based on data from trials in Britain and Brazil. On the same day, the panel asked Hyderabad-based Bharat Biotech, a well-known manufacturer of more than a dozen vaccines sold worldwide, to supply more information about the effectiveness of its Covaxin shot, which was still in the critical third stage of clinical trials.

The panel granted approval to Covaxin the following day — but offered little explanation publicly as to why. Indian news media have also reported irregularities in the vaccine’s testing, with some volunteers saying they were led to believe they were receiving an approved shot, not participating in a trial. The company denies allegations of wrongdoing.

The opaque process has led to allegations that the government has rushed the vaccine into use to promote the nationalist Modi’s mantra of a self-reliant India.

“Controversies always create doubts,” said K. Sujatha Rao, a former Indian health secretary. “So the government is definitely trying to communicate confidence in the safety aspects. But the process can impact on perceptions.”

The stakes are high for a country that has recorded more than 10 million coronavirus infections and 151,000 deaths, among the most in the world. India’s economy shrank by 10.3% in 2020, according to the International Monetary Fund, and weeks of protests against new agrarian policies have further buffeted Modi’s government.

Yet early fears that the coronavirus would lay waste to overcrowded slums and overwhelm rural areas with poor health infrastructure haven’t come to pass. India’s daily tally of new infections peaked in mid-September and has declined steadily since, which officials see as a sign that herd immunity may be starting to take hold. In the southern state of Tamil Nadu, for example, studies suggest that 60% to 70% of people have been exposed to the virus, making it unlikely that they could be reinfected.

“The number of susceptible people has been exhausted or is nearly exhausted, so the curve is going down,” said Chandra Mohan, a senior health official in Tamil Nadu. “Under these circumstances, the vaccine rollout is good, but a little extra time taken here or there to ensure a proper rollout will not make any difference.”

Mass screenings and quarantines have helped contain the coronavirus in Dharavi, home to 1 million people.

To prepare for the vaccinations, India conducted nationwide dress rehearsals in recent weeks, with health workers gathering at medical centers, registering patients, rolling up their sleeves and tallying data — everything except actually injecting people.

India is relying on an existing immunization program that administers routine shots to 55 million people every year. Health officials have trained more than 200,000 vaccinators, readied 90,000 refrigerators and freezers to store the vaccines and rushed to set up an online portal to track recipients and drug supplies.

“If all goes well and if the plans are indeed executed as designed, it may very well become an exemplar in how to do a very large-scale rollout of the vaccine,” said Yadav of the Center for Global Development.

Among the hurdles is availability of the vaccines. The Serum Institute has pumped out 70 million doses of Covishield, the AstraZeneca-Oxford shot, and is expected to increase production to 100 million doses a month by March, but that would still fall short of the 600 million doses India needs for the first phase. The company has indicated that it will focus on supplying India for several months before exporting doses to other countries.

Bharat Biotech reportedly has a stockpile of 20 million doses of Covaxin, with the goal of producing 700 million more by year’s end.

Indian officials have indicated that they do not plan to inoculate all 1.3 billion people in India, believing the country could reach herd immunity after the first phase of shots, which will cover less than a quarter of the population.

Experts say the country has enough health workers, syringes and cold storage facilities — the vaccines must be kept at a temperature of 35.6 to 46.4 degrees Fahrenheit — but worry that other immunizations could be delayed or forgotten as the system focuses on COVID-19.

More stories from Asia

Anant Phadke, senior advisor to a healthcare charity in the western city of Pune, said the infrastructure for vaccinating newborns and pregnant women was already overburdened.

“Over the past 40 years, the staff has not increased according to the population,” he said. “The existing public health system is barely managing the workload. If the existing staff bears a major burden of the [COVID-19] inoculation drive, it could sideline routine vaccinations.”

Pune, in Maharashtra state, is among the worst-hit districts in India, with more than 350,000 coronavirus cases. Officials said their biggest challenge would be reaching rural areas, where people often must travel hours to get to a health center.

Bhagwan Pawar, a local health official in the western town of Maan, 100 miles from Mumbai, said the area’s health centers had enough storage facilities and 48 hours of backup electricity in case of power cuts. Health workers aim to vaccinate 100 people per location per day, he said.

Local health officials declined to comment on the safety of the government-backed Covaxin vaccine. But Avinash Bhondve, former president of the Indian Medical Assn. in Maharashtra, said the medical community had its doubts.

“The government has not assured that it is 100% safe,” he said.

Times staff writer Bengali reported from Singapore and special correspondent Parth M.N. from Mumbai.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.