Wetlands get treated as the ugly duckling of L.A.’s natural spaces. It’s time to change that

- Share via

Happy World Wetlands Day from the driest big city in the world.

OK, that’s not true. We may think of our city as arid, but Los Angeles harbors its very own rich wetlands (plus, Yuma beats us on aridity any year). The Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve, between Playa del Rey to the south and Marina del Rey and Venice Beach to the north, represents the past, present and future of our city. These ancestral waterways once harbored a fertile ecosystem with which the Tongva coexisted, but the area was recklessly defaced by Marina del Rey construction and continues to struggle with fires and trash from local encampments.

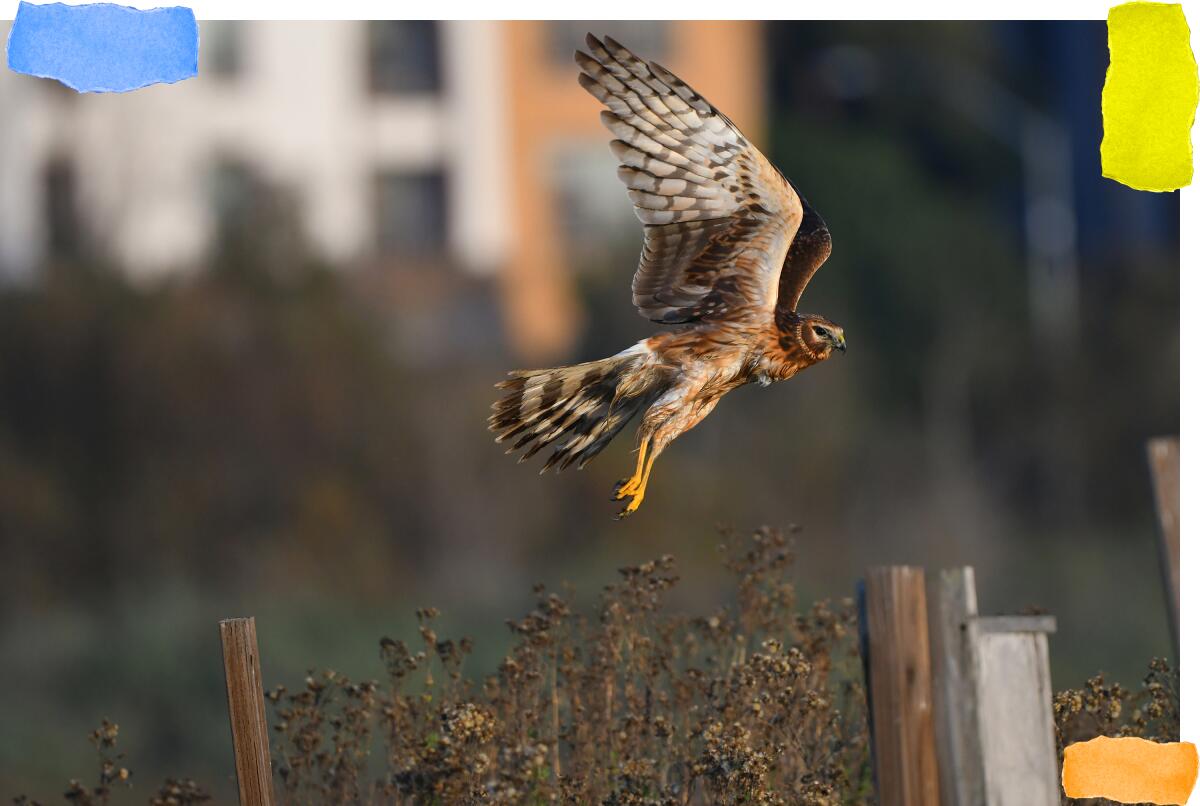

Now, the reserve is slated for a new conservation effort by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, which could lead to a golden age in which humans, animals and plants thrive. Once completed, the Ballona Wetlands Restoration Project will include a 600-acre nature space paralleled only by Griffith Park — but on the crowded west side. For an idea of what that might be like, take a peek here.

Get The Wild newsletter.

The essential weekly guide to enjoying the outdoors in Southern California. Insider tips on the best of our beaches, trails, parks, deserts, forests and mountains.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

I spoke with Patrick Tyrrell, manager of habitat restoration and upper education at Friends of Ballona Wetlands, which has been fighting to protect our wetlands since 1978. Head to the Reserve for cleanup days and habitat restoration, and you’ll spot beautiful native friends such as great blue herons and flame skimmer dragonflies — and, if you’re lucky, maybe even a furry little mammal called the Southern California salt marsh shrew.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why are these wetlands so important for Angelenos to understand and support?

Wetlands are critical habitats considered on par with rainforests or coral reefs in terms of the biodiversity they attract. They’re these incredible transitional areas between land and water with species that aren’t found anywhere else. They’re natural filters for pollution, and they protect the coastline from flooding and perform nutrient cycling. They store and sequester carbon. They’re just an incredible ecosystem. In addition, they provide [a space] for people to get outside and breathe air and walk around, which is so lacking in L.A.

So they just need better PR.

Well, for sure [laughs]. It’s a lot of mud and shrubby little stunted plants sometimes, so it doesn’t necessarily fit with what we think of as a beautiful natural space. That’s really at the core of what our organization does: getting people out there and getting those dynamic interactions across to them with field trips and volunteer events.

What’s the history of our very own Angeleno wetlands?

Today, we have about 600 acres that are the remnant system from a much more complex marsh ecosystem. Historically, the wetlands stretched from Playa del Rey and Marina del Rey to Venice, east to Lincoln Boulevard, and would have been a mix of freshwater, saltwater and dunes. The land was a very important village site for the Tongva people for much of the last few thousand years. When millions of people moved to L.A. and the city grew, you had agriculture, ranching, oil and gas exploration, racetrack and railroads built through there. Little by little, the wetlands altered through human activity.

Was there a devastating event that really damaged our wetlands?

In the early 1930s and ’40s there was a channelization of the [Ballona] creek, with a system of levees that began to flush water to the ocean, severing the land from the water, which had a devastating effect. Then came the construction of Marina del Rey in the late ’50s and early ’60s. Sediments being dredged to create the harbor were dumped onto the wetlands. A significant part of the wetlands are buried under a few million cubic yards of sediment — at some places, the wetlands are piled 15 feet high above their historic elevation.

In 2003, the state of California stepped in to purchase the property and designate it an ecological reserve. It’s been a journey to figure out how to best restore it.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has big plans for restoration. What are your thoughts on those?

We feel the project is needed and extremely important. They have an ambitious plan to remove the sediment that was dumped, remove big sections of existing levees to allow more water into the wetlands, and construct new berms that would serve the purpose of flood protection while opening up the system to more water. At Area A, which is north of Ballona Creek, directly adjacent to the Marina, you have what is sort of a degraded upland habitat where water will pond after it rains ... that will be restored to a salt marsh estuary habitat.

More than half of the Reserve is covered with nonnative invasive plants like mustard and ice plant. How are you combating that?

We’re giving our native species a helping hand. We’re growing native plants on-site and planting them back into those restoration areas.

Seacliff buckwheat is one of our most important plants, and the host plant for one of our unique local species: the El Segundo Blue Butterfly. The caterpillars will only eat the buckwheat, and adult butterflies will only eat the buckwheat. Ten years ago, the butterfly showed up because of all the work done by volunteers planting seacliff buckwheat. As result, we have a federally recognized native species on the way to recovery.

What other animals might visitors see?

The legless lizard is a cool and beautiful lizard species — not a snake, but truly a lizard. It just doesn’t have arms and legs. Then there are small mammals that few are aware of, like the salt marsh shrew, which is hard to spot — I’ve never actually seen it.

This newsletter has such an avid birding readership. Can you tell me about some of the birds who live there?

One of our important bird species is the Belding’s Savannah Sparrow, a species only found from Santa Barbara County to northern Baja. It lives, forages and nests there. If you lose the salt marsh habitat, you lose the bird. We’ve seen recovery in the past 20 years with work done to fix the tide gates allowing tidal flow into the marsh. All of these ecosystems are woven together and interconnected.

From what I read, the Ballona Wetlands are like a rest stop for birds flying long distances and migrating.

Just like people need to stop to charge their electric vehicle or get food or get gas, so do birds. Because of the extensive urbanization of Southern California, those rest stops are diminished in many ways, so Ballona really represents one of those critical resting stops.

What role does educating youth play in our hopes for the wetlands?

We host about 7,000 kids every year. A lot are coming from Title 1 schools and don’t have regular access to big open spaces there. They’re down there planting plants and weeding. They’re introduced to the importance of the wetlands and understanding these ecosystems and talking about the cultural history of land.

We talk about the human impact as far as negative impacts of development and destruction, but we’re also looking at the creek and talking about trash and pollution, how trash gets back to water. We want students to leave feeling both community and interconnectedness between where they live and the wetlands. It’s empowering them for the future — that seed that will turn them into future scientists and stewards.

You have some events coming up — chances for folks to roll up their sleeves and weed, plant native plants, clean up, visit.

Yes, we have an extensive calendar, with freshwater marsh tours, habitat restoration projects, salt marsh and dune tours, a gardening club. Check it out.

3 things to do

1. Ferment food and pet baby goats. Trek to Angeles Crest Creamery on Sunday from 10:30 a.m. to 3 p.m. for a day of learning how to ferment sauerkraut-type foods, then visiting baby goats. The picturesque ranch occupies 70 acres in the San Gabriel Mountains. The class is led by master forager and fermentation teacher Pascal Baudar, who possesses broad knowledge of wild plants and how to maximize their vivid flavors. He’ll provide snacks and drinks (having tried his food, I know you’ll want to devour it). The cost is $95; buy tickets here. Don’t forget to bring your own head of green cabbage, along with a few heads of bok choy, a sharp knife and a couple of pint jars.

2. Unwind on a Black men-led hike. Jelani Nattey started Black Men Hike after his wife pushed him to start getting outdoors more and his stress and anxiety dropped drastically. He wanted to create a space for Black men away from “the stressors of living in a systemically oppressive society,” and the affinity group was born in 2019. What began as a casual meetup became a 501(c)(3) in early 2022 to expand its resources and reach. The group meets on the first Saturday of each month; the next free hike is at the Eagles Nest Trail Loop on Saturday from 8:30 a.m. to 12 p.m. Go here for GPS coordinates and more information, and sign up for emails to get the 411 on future hikes.

3. Have fun with fungi. This event sponsored by the Los Angeles Mycological Society could be considered mushroom Coachella. On Sunday from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m., join mushroom lovers at the South Coast Botanic Garden for the Wild Mushroom Fair, which will feature foraging walks, growing demos, art and vendors. Keynote speaker Christian Schwarz will present his address, “Making Scents of Fungi: From Stench to Perfume.” Admission is included with the cost of a ticket to the gardens, which are $15 for adults, $11 for seniors and students, $5 for children 5 to 12, and free for children under 4. No RSVP is needed. For tickets, go here.

The must-read (and listen)

Have you been following the story of the Colorado River, which flows from its Rocky Mountains headwaters to a dry Mexican delta? On Jan. 6, The Times kicked off a dynamic multimedia project featuring stunning videography, photography and a new podcast series hosted by Gustavo Arellano, detailing the drastic crisis of a quickly drying river that provides water to 40 million people (including us in L.A.) and irrigation to more than 5 million acres of farms.

This week’s installment highlights the relationship between our Indigenous communities, including the Fort Mojave tribe, and the West’s primary source of water. Though tribes have rights to 25% of the water supply, they have been denied from enacting those rights, per reporting by senior podcast producer Kasia Broussalian. The podcast shares so much more, including the voices of those who’ve been disenfranchised from not only the water itself, but the decision-making process about the water that supposedly belongs to us all. It’s well-worth a listen — and it’s a worthy reminder.

As we set out to hike waterfalls from the fresh rain, let’s remember to conserve what water we can. Bring water in a reusable jug rather than a plastic one. If you use a Grayl UltraPress Purifier or LifeStraw to clean local water, that can help prevent pollution too. To survive this crisis, we’ll need native landscapes, rainwater storage and grey water systems, not water-hungry lawns and pools. We’ll have to keep finding ways to farm with less water, like smart digital irrigation and drip irrigation. We need to “re-wild,” turning large landscapes natural again, rather than feeding thirsty golf courses. Cutting down on high water-consumption foods (like beef) even a few times a week, can help. (I’m ready for the hate mail.)

Happy adventuring,

Check out “The Times” podcast for essential news and more.

These days, waking up to current events can be, well, daunting. If you’re seeking a more balanced news diet, “The Times” podcast is for you. Gustavo Arellano, along with a diverse set of reporters from the award-winning L.A. Times newsroom, delivers the most interesting stories from the Los Angeles Times every Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts.

P.S.

Did anyone see the gorgeous snow on the San Gabriel Mountains earlier this week? I could see it from the Rose Bowl as I took a brisk walk. Mornings like that, it feels like we’re living in a small Colorado mountain town, the air crisp and our skis just waiting to be strapped on.

For more insider tips on Southern California’s beaches, trails and parks, check out past editions of The Wild. And to view this newsletter in your browser, click here.

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.