- Share via

OKLAHOMA CITY — For years, Doug Mathis had viewed the Dodgers with a mix of admiration and curiosity, marveling from afar at their renowned player development system.

As a Texas Rangers pitching coach the last three seasons, and a minor league staffer for the Seattle Mariners and Toronto Blue Jays before that, Mathis figured there was a privileged formula behind it all, a “secret door” protecting the keys to the Dodgers’ success.

This year, hired to be the team’s triple-A pitching coach in Oklahoma City, he finally got a peek inside.

“I thought it was gonna be like seeing the Wizard of Oz,” he said. “You get behind the curtain and see all these tricks.”

What he found was even more surprising.

Dodgers’ farm system success

This is the first in a three-part series analyzing the Dodgers farm system’s decade of success, and how it has helped turn the club into one of baseball’s best organizations.

⚾ Part 2: Meet the Dodgers double-A rotation, the epitome of their ‘ridiculous’ pitching pipeline

⚾ Part 3: Why a potential pursuit of Shohei Ohtani will make the pipeline more important than ever

Over the last nine years, the Dodgers have had one of the highest-rated, most productive farm systems in baseball, churning out waves of prospects and a parade of major leaguers without many high draft picks, large signing bonus pools or any rebuilding seasons to replenish their system.

For a time, they did so by getting a head start on baseball’s analytics age, embracing the use of data, technology and cutting-edge training programs to reimagine their player development process.

Now that the rest of the industry has closed that gap, the Dodgers are prolonging their reign with a different emphasis.

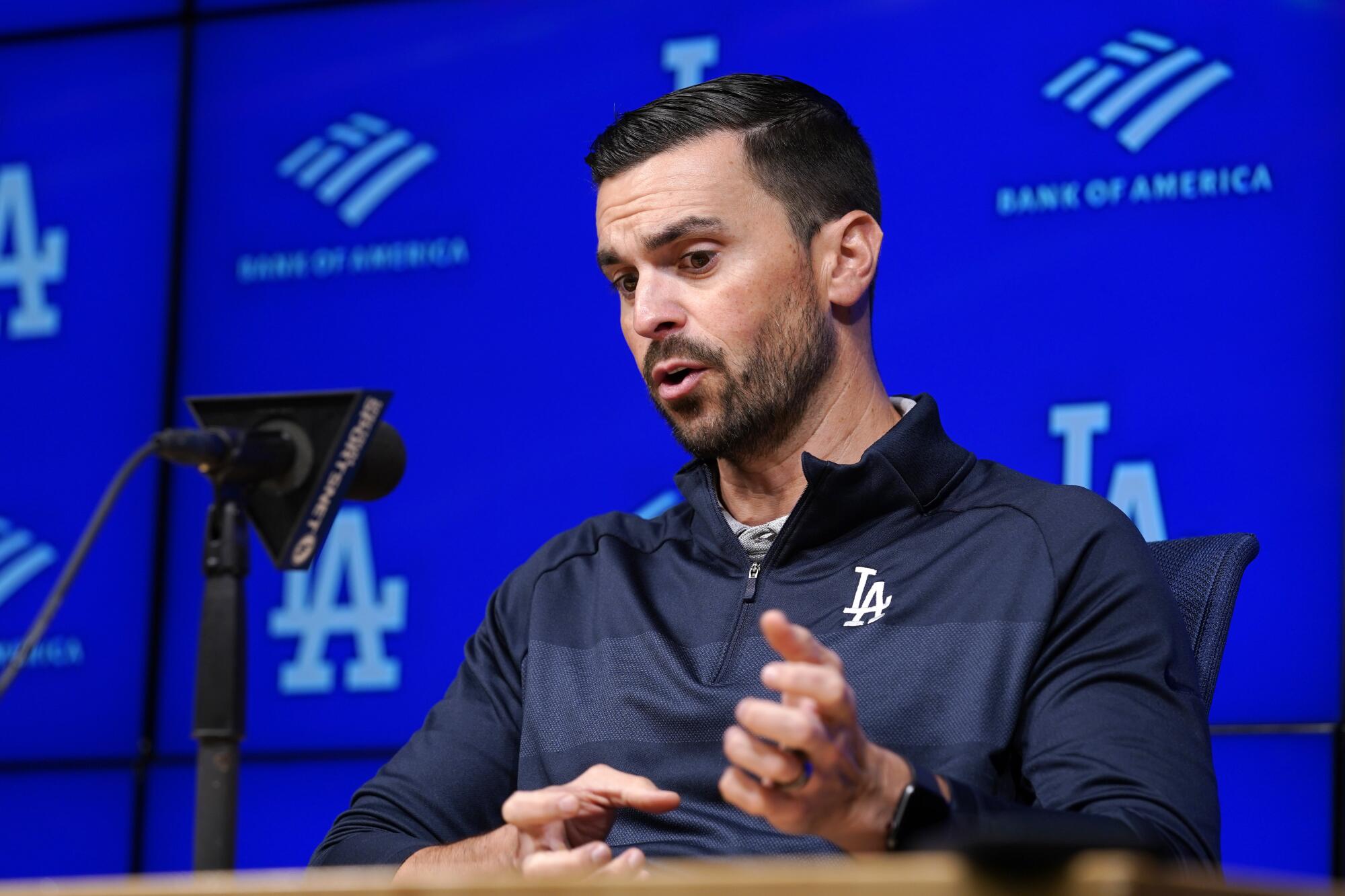

“It’s a lot about how we’re working together, making sure we’re delivering a clear message to the player, and trying to limit the confusion,” general manager and former farm director Brandon Gomes said. “I think that’s the separator.”

Ask around the Dodgers organization and similar sentiments emerge — coaches praising the cohesion they’ve built between various departments and staff members of differing baseball backgrounds; players reveling in the consistent, concise plan crafted for each of them.

It might seem like a modest explanation. The club has ranked among Baseball America’s top 10 farm systems for nine straight years, the longest active streak. They have eight prospects in MLB Pipeline’s Top 100 player rankings, tied with Baltimore for most. They have accumulated the third-most wins above replacement from players they’ve drafted since 2015, according to the Down on the Farm newsletter.

“We have a lot of people in really good positions that are smart, intelligent and trusted to do their jobs,” Mathis said. “Not to say that doesn’t happen anywhere else. But I think the information is there, the resources are there and … it’s just a really trusting environment of how we go about our business.”

To understand how the Dodgers’ farm system could shape their present and future, The Times visited three of their minor-league affiliates and spoke to more than 20 players, coaches and evaluators within the organization and around the industry.

Their answers painted the Dodgers as a developmental juggernaut, one that has maintained a deep and desirable pool of young players — many of them later-round picks, overlooked prospects and unexpected success stories with a wide variety of skill sets — to become the envy of the sport.

“Analytically, in terms of communication within the system, and then in their identification of players,” one rival scout said, “they’re really at the top of their game.”

It’s not a perfect system. The Dodgers still are trying to usher in a new generation of high-impact big leaguers and they haven’t developed hitters quite as consistently as pitchers in recent years. But for a team balancing championship aspirations and a sky-high payroll, player development has become the lifeblood of the organization.

“Your heart and soul has to be player development,” Gomes said. “That has always been a guiding light for us.”

In one breath, John Shoemaker can rattle off a litany of modern baseball terminology: exit velocity, horizontal break, spin rate. All of them important in prospect evaluation.

In the next, the 66-year-old manager of the Dodgers’ single-A Rancho Cucamonga affiliate will change gears, referencing the late Tommy Lasorda to blend old-school wisdom with the new-age philosophies.

“Tommy said it best,” Shoemaker declared, quoting the Dodgers’ legendary former manager. “The road to success comes through the avenue of hard work.”

Shoemaker would know.

A former Dodgers minor league infielder who entered coaching in 1981, he has worn just about every hat you can in player development. Hitting coach to defensive instructor. Assistant field coordinator to manager of 13 affiliate teams.

Since 2015, he’s had an honorary “C” on his jersey as the Dodgers’ “captain of player development.” And his presence epitomizes the culture the Dodgers have tried to establish throughout the minors.

“It starts with the ballplayers’ buy-in,” Shoemaker said, “and the coaches’ collaboration throughout the organization.”

While the farm system historically has been strong, it was the club’s sale to the Guggenheim ownership group that spawned this era of excellence, starting with an influx of player development resources and a sudden spending spree on the international market.

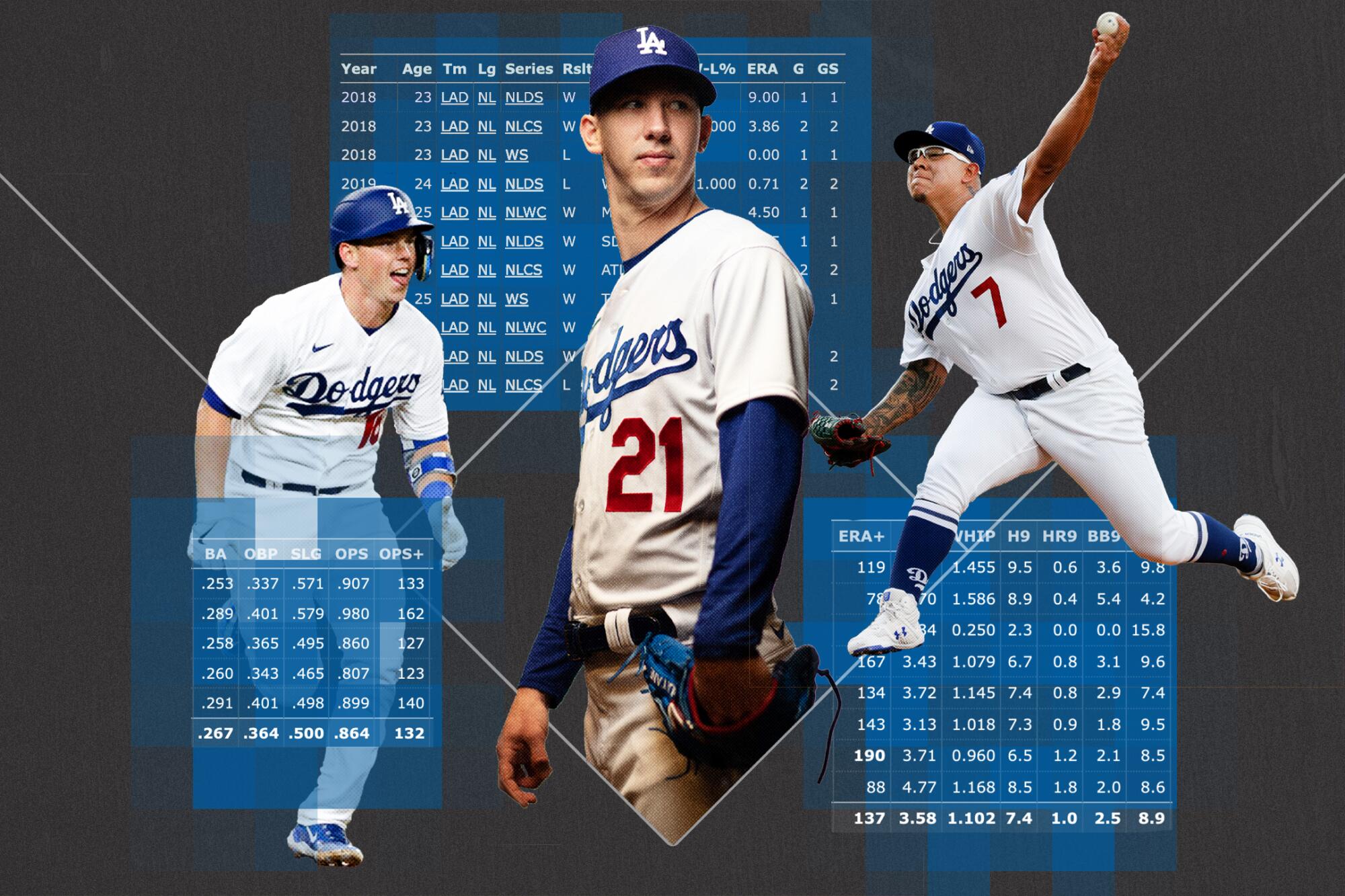

Soon after, a new wave of prospects, led by Corey Seager, Cody Bellinger, Julio Urías and Walker Buehler, began to emerge.

And, in the second draft under President of Baseball Operations Andrew Friedman and his scouting director, Billy Gasparino, in 2016, the team struck gold with a staggering 14 future big league selections, including Will Smith, Gavin Lux, Tony Gonsolin and Dustin May.

That young core helped catapult the Dodgers into contention and eventually served as the backbone of their 2020 World Series team.

Along the way, however, it should have gotten harder for the team to sustain its farm system depth.

Because of MLB rules designed to promote parity and penalize big-spending teams, the Dodgers haven’t had a top-20 draft pick since 2016. Their bonus pools for signing international players often have been smaller than those of most clubs.

The Dodgers return to Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas, for the first time since winning the World Series in the pandemic-shortened season.

Under similar circumstances, other big-market teams usually have fallen “off a cliff,” Friedman cautioned this winter, forced to trade big-league players and endure a rebuilding cycle.

In hopes of avoiding that fate, the Dodgers doubled down on player development.

Many of their strides came through cutting-edge advancements, the team early to implement new technology like the Rapsodo tracking system (which provides data on pitches and batted balls to find areas of improvements for each player) and KinaTrax motion capture systems (which can give biometric readings on every part of a player’s delivery or swing).

They’ve embraced non-traditional training styles.

Pitchers were put through programs modeled after the Driveline training center, helping cultivate desirable traits like fastball velocity and increased spin rates.

Hitters were taught the importance of swing plane and launch angle, learning from innovative instructors such as Craig Wallenbrock and Robert Van Scoyoc (now a hitting coach with the major league team) to optimize the efficiency of their swings.

But the Dodgers didn’t abandon conventional wisdom either.

The Aug. 1 MLB trade deadline is approaching and the Dodgers are in need of starting pitching, relief pitching and bench help. Will they make a move?

While their director of minor league pitching is Rob Hill, a 28-year-old former NAIA college pitcher who taught at Driveline before being hired three years ago, they also lean heavily on veteran coaches like Don Alexander and Charlie Hough — baseball lifers more than double Hill’s age whose wealth of knowledge has rounded out the pitching department’s training methods.

In Oklahoma City, manager Travis Barbary is tasked with overseeing the final step up the minor-league ladder, the Dodgers leaning on his 28 seasons of experience as a coach in their system to prepare prospects for the pressure of the big leagues.

And then there is Shoemaker, who still uses Lasorda-isms with his class-A players, only now to help translate some of the more advanced baseball concepts.

“Tommy once said, ‘Sooner or later, somebody is gonna be able to time a bullet if the ball is thrown straight,’” Shoemaker said while discussing the importance of pitch design and movement.

“We’re able to think outside the box,” he added, reflecting on all that has changed within the team over the last decade. “Or, think like there’s no box at all.”

On one of his first days with the Dodgers, during a rookie camp at their spring training facility in Arizona, Emmet Sheehan was struck by what he heard from their player development staff.

“From when you show up, they tell you, basically, ‘If you come up to us and ask us why we are doing something, and we can’t tell you how it translates on the field, you don’t have to do it,’ ” recalled the 23-year-old pitcher, a sixth-round draft pick in 2021 who already made his way to the big leagues.

“They teach us the reason behind everything we do,” he added. “And everything is personalized to the player.”

It’s in moments like these that the Dodgers’ organizational philosophies are put into practice — where their ability to eliminate silos between coaches of different backgrounds, and departments of different expertise, helps them impact their players in myriad ways.

Almost every prospect the team drafts goes through a similar mini-camp experience. They arrive at the Camelback Ranch facility and immediately begin developing skills in the areas they are lacking.

For Sheehan, a wiry right-hander who began filling out his 6-foot-5 frame only near the end of college, that meant going through a specialized strength program. Not only did he lift weights and add muscle, but he also attended classes in which coaches explained how his body worked and how the increased strength would benefit his delivery.

“It was probably a couple hours of classroom sessions every day learning about that stuff,” Sheehan said. “It was really interesting.”

Other prospects have different stories, highlighting other hallmarks of the development system.

When James Outman was drafted in the seventh round in 2018, the scouting department knew he would be a big project. He was an outfielder with natural pop but a raw prospect with plenty of mechanical flaws in his swing.

Whether it’s on your list to take in a game at every stadium or you just want to soak in the atmosphere at a specific field, here’s a guide to all 30 ballparks.

So when he entered the organization, the scouts and minor-league coaches already had worked together devising his plan. Outman immediately went to work with instructors like Wallenbrock, skipping the slow professional orientation others typically get for a crash course in player development.

“When you talk about smart organizations, it’s two or three departments working together,” ESPN draft analyst Kiley McDaniel noted during the network’s telecast of this year’s event. “You feel like that’s everybody. No, it’s like four teams. It’s a very short list of teams that are good at that.”

By all accounts, the Dodgers are one of them.

Their culture of cross-pollination and collaborative planning stretches all the way to their nutrition choices, where even in Rancho Cucamonga they have a team of chefs for their class-A players who haul a trailer of fine foods and cooking equipment across the California League — an idea that originated with Gabe Kapler, who preceded Gomes as the Dodgers’ first farm director under Friedman.

“When you’re putting that kind of attention to the way you’re feeding players,” one rival scout said, “then you’re giving a lot of attention to the other areas as well.”

It doesn’t mean all Dodgers staffers always see things the same way. On the contrary, the team not only embraces debate among coaches, instructors and player development departments, it actively elicits it, holding open forums on all sorts of decisions in person, over email or through their Slack messaging channels.

The exercise can be awkward. Differing opinions on young players is a virtual given.

“The challenge is getting everybody to come to an agreement of a path,” Gomes said, “knowing that even if this doesn’t work, we’re all behind it.”

While open debate is hardly a novel concept, the Dodgers have tried to take it to productive extremes.

This past offseason, for example, Hill organized biweekly Zoom calls with the pitching staff, tasking groups of coaches with assignments to complete before the next session.

One such project: giving presentations on how they would improve the pitching department if they were in charge.

“The presentations were made collaboratively among different groups of coaches,” Hill said. “We had experienced guys, younger guys, Latin American coaches — everything kind of melded together.”

And it’s from those sessions, the Dodgers believe, more advancements in player development can be made, taking their melting pot of ideas and pouring it into players of different molds, skill sets and profiles.

“People in the industry, in general, regard feedback as negative,” Hill added. “But the more feedback you offer, the more feedback you accept, the more information you have. The better you can be in the future.”

For Barbary, the conversations never get old.

Since he became Oklahoma City’s manager in 2019, the Dodgers have promoted 33 players for their major-league debuts.

And in almost every case, it is Barbary who informed them of the news, delivering the happy decision in middle-of-the-night phone calls, celebratory clubhouse announcements and emotional office meetings.

“Some guys are totally in shock, like they weren’t expecting it all,” Barbary said. “Sometimes guys kind of knew it was coming, but when we tell them, the reality hits. Some guys are really happy. Some guys get emotional and they hug on you and cry.”

Not all of those players have gone on to stardom. Of that group, only three have been All-Stars (Smith, Gonsolin and Josiah Gray). Slightly more than half have been better than replacement level, according to Baseball Reference.

But this year, all but four of those 33 have been on major league rosters, a sign of the Dodgers’ ability to create consistent depth from their minor-league ranks.

After two seasons battling injuries and inconsistency, Mookie Betts is playing at a superstar level for the Dodgers.

More than anything, that has been the true value of their player development system. As the team’s payroll has climbed, centered more and more around superstar acquisitions like Mookie Betts and Freddie Freeman, its financial flexibility has shrunk.

Producing homegrown stars is a plus. But providing inexpensive and dependable depth, or an ever-available prospect pool from which to facilitate trades, is a necessity — one the player development department seemingly has mastered.

“It is kind of amazing, the guys that we’re able to produce on a yearly basis,” Barbary said. “But at the end of the day, that’s the expectation here: develop and win a championship in L.A. Everybody’s on the same page.”

As good as they are, the results could be even better.

They’re waiting to find a true breakout performer from this year’s rookie class, one headlined by top prospects such as Bobby Miller, Gavin Stone and Miguel Vargas whom the team kept despite trade rumors the last year and a half.

They have missed on some recent first-round picks, most notably Jeren Kendall (2017) and Kody Hoese (2019).

And some of their recent success stories have been slowed by injuries, most notably elbow problems for Buehler and May.

“There’s been some really, really impressive stuff,” the rival scout said. “But at the same time, they probably could have done better.”

The rivalry isn’t big enough to prevent the Angels from sending Shohei Ohtani to the Dodgers, who can offer more high-end prospects than anyone else.

Nonetheless, their flow of talent from the minors to majors remains strong — epitomized by the sheer quantity of call-up conversations Barbary has had in recent years, and a meaningful tradition that accompanies each one.

Whenever a prospect makes his major league debut, an email from either Gomes or his successor as farm director, Will Rhymes, will land in the inbox of coaches across the organization. The executives will write up a profuse thanks to everyone who had a hand in helping the player climb through the system.

“There’s so many people that put crazy amounts of time and energy into the development of each guy,” Gomes said. “Whatever the vision is of the coordinator, or the bigger group, those coaches are the ones executing it. Which is everything.”

The recognition is appreciated, serving as one more small piece that brings the Dodgers’ player development process together.

“Sometimes you do feel like, in the minor leagues, especially at the lower levels, you’re so far removed from what happens in L.A., you feel like what you do doesn’t really impact the big league club,” Barbary said. “So when those emails go out … I think that’s important. People want to know they’re doing things the right way, and that they’re doing a good job and helping guys get to the big leagues. It just keeps you motivated to do it again. It keeps you going.”

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.