Legendary Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda dies at age 93 of a heart attack

- Share via

Tommy Lasorda’s body began to fail him in recent months, but his passion for the Dodgers never wavered. The man who always claimed he bled Dodger blue out of loyalty to the organization had one last mission to accomplish, one more triumphant moment to experience.

He was granted that moment in October, when the Dodgers defeated the Tampa Bay Rays to win the World Series — their first championship since he guided them to the title in 1988. “He willed himself to live this long and to watch that world championship,” former Dodgers pitcher Orel Hershiser said. “He willed himself to stay active with baseball and to be impactful on a daily basis.

“He’s impacted us all in so many ways, the L.A. community, the baseball family, all of the world of baseball. But I believe Tommy Lasorda had no boundaries. On a daily basis there were no boundaries to something positive, something about winning, that he could do.”

Lasorda, who in 20 years as the Dodgers’ manager won two World Series championships, four National League pennants and eight division titles, died of a heart attack Thursday night at 93. One of the few remaining links to the club’s Brooklyn roots, he had spent 71 seasons with the Dodgers and was a vibrant and voluble presence.

“He let anyone know the importance of putting on the Dodger uniform and what it means to be a part of this organization, and I think this is something that has been real for decades,” manager Dave Roberts said. “It’s our job now going forward to make sure his legacy continues to live on. It encompasses a lot to be a Dodger, and no one exemplified that more than Tommy.”

Lasorda had been in and out of the hospital in recent years for heart, back and shoulder problems. He had been released from an Orange County hospital Tuesday following an extended stay and was at his Fullerton home Thursday when he suffered a sudden cardiopulmonary arrest, according to the Dodgers. He was transported to the hospital with resuscitation in progress and was pronounced dead at 10:57 p.m.

Hershiser, who credited Lasorda for molding him as a pitcher and as a person, said Lasorda had hoped to live to 100.

“That was probably the only thing that he set out that he didn’t make,” said Hershiser, who kept in touch with Lasorda via FaceTime. “But you know what, he made it a lot farther than a lot of us would. I hope we live that full a life.”

Said Ned Colletti, a former Dodgers general manager: “He could make you laugh. He could motivate you. He could bring you confidence. He could question something to get you to think differently. And he could love you. And he could do all of that in about five minutes. There’s only one of him. There’s only one.”

A friend to presidents and Little Leaguers, a devout Catholic with a talent for rapid-fire profanity, a self-promoter who tirelessly raised funds for convents and disaster victims through banquets and speeches, Lasorda spanned several eras in baseball and — along with Vin Scully and Sandy Koufax — achieved near-mythical status among loyal Dodger fans.

“My family, my partners and I were blessed to have spent a lot of time with Tommy,” said Mark Walter, Dodgers owner and chairman. “He was a great ambassador for the team and baseball, a mentor to players and coaches, he always had time for an autograph and a story for his many fans and he was a good friend. He will be dearly missed.”

Tommy Lasorda, who died Thursday night of a heart attack at age 93, bled Dodger Blue nearly his entire life, spilling it across every corner of the world.

“In a franchise that has celebrated such great legends of the game, no one who wore the uniform embodied the Dodger spirit as much as Tommy Lasorda,” Dodgers president and CEO Stan Kasten said. “A tireless spokesman for baseball, his dedication to the sport and the team he loved was unmatched. He was a champion who at critical moments seemingly willed his teams to victory. The Dodgers and their fans will miss him terribly. Tommy is quite simply irreplaceable and unforgettable.”

He was voted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the veterans committee in 1997, his first year of eligibility, and the Dodgers later retired his uniform number, 2.

Four years after he retired as a major league manager, Lasorda guided the lightly regarded U.S. Olympic baseball team to a gold medal at the 2000 Sydney Games.

He retained the title of special advisor to the Dodgers’ chairman, most recently reporting directly to controlling owner Mark Walter.

His last known public appearance was at Game 6 of the 2020 World Series in Arlington, Texas, where he saw the team he guided for so many years finally win another title.

“[Lasorda’s] passion, success, charisma and sense of humor turned him into an international celebrity, a stature that he used to grow our sport,” MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred said in a statement. “Tommy welcomed Dodger players from Mexico, the Dominican Republic, Japan, South Korea and elsewhere — making baseball a stronger, more diverse and better game.”

As a player, Lasorda was a fearless but unpolished left-handed pitcher who was demoted to the minor leagues when the Dodgers needed to open a roster spot for a promising kid named Sandy Koufax. Lasorda compiled an 0-4 record over parts of three seasons with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Kansas City Athletics and spent 14 seasons in the minor leagues before he began working his way up the ladder of the Dodgers organization as a manager.

Lasorda ate with the same gusto that he managed, earning the nickname “Tommy Lasagna.” Although he famously became a pitchman for a weight-loss aid and shed 40 pounds on a dare in 1988, he was instantly recognizable for his rotund figure and the sagging pouches under his eyes.

Despite his 1,599 victories and the Dodgers’ World Series titles in 1981 and 1988, Lasorda was never considered a great innovator or tactician. But he had an unerring gut sense of how to manage players, and was, unquestionably, a great motivator. And through seven decades as a player, scout, coach, manager, interim general manager and advisor, he remained an unabashed cheerleader for the Dodgers.

“No one knows how good a manager he is — it’s an imprecise science — but he was good enough to get in four World Series and he was the best there ever was at taking a bunch of moderately talented kids out of the minor leagues and making them think they were the 1927 Yankees,” Times columnist Jim Murray wrote in 1990. “No one has yet been able to figure to this day how he got the 1988 team in the World Series, never mind winning it in five games.”

Legendary Dodgers manager and baseball ambassador Tom Lasorda died of a heart attack Thursday at age 93. He was always quick with a quip, and here are some.

Thomas Charles Lasorda was born Sept. 22, 1927, in the Italian American section of Norristown, Pa., outside Philadelphia. The second of Carmella and Sabatino Lasorda’s five sons was pugnacious, but as much as he loved fighting, he loved baseball even more. Money was tight, though, and he had to work every summer. He took jobs as a bellhop and laid track for the Pennsylvania Railroad.

He was signed by the Phillies out of Norristown High before the 1945 season. He spent two years in the military and was chosen by the Dodgers in the 1948 minor league draft. Although he thrived in the minors, once recording 25 strikeouts in a Class C game, he couldn’t crack the Dodgers’ strong pitching staff. He made his major league debut on Aug. 5, 1954, appearing in four games that season and four the next. His most noteworthy feat was tying a record by unleashing three wild pitches in a single inning.

He was purchased by the Athletics in March 1956 and pitched in the minors until 1960. Lasorda became a scout for the Dodgers in 1961, then in 1965 became a manager in the Dodgers’ minor league system. In Pocatello, Idaho, and Ogden, Utah, he sold tickets, took tickets and cooked team meals. He’d squirt opposing fans with water guns or stage fights, anything to ignite team spirit.

His antics were entertaining, but he backed them with good results and was promoted to manage at the triple-A level in Spokane, Wash., from 1969-71 and in Albuquerque in 1972. His teams won five pennants in seven seasons, and 75 players he managed made it to the major leagues.

By the time Lasorda wore a major league uniform again, this time as a coach, the Dodgers had long before left Brooklyn for Los Angeles. He became the third base coach in 1973 for Walter Alston, the club’s longtime manager.

Alston retired on Sept. 29, 1976, after Lasorda had rejected a number of offers from other teams to manage while waiting for Alston to step aside. Lasorda inherited a terrific infield of Steve Garvey at first base, Davey Lopes at second base, Bill Russell at shortstop and Ron Cey at third base. Lasorda had managed all four in the minors.

Lasorda’s personality ensured that the atmosphere around the Dodgers would be lively. The first thing he did in 1977 was move the manager’s office from the cubicle Alston had used to a larger room that could hold a TV set, couches and a postgame buffet. He invited players to drop in, sample the food and chat.

Fans loved the new, more colorful Dodgers. Home attendance surpassed 3 million for the first time in 1978 and peaked at 3.6 million in 1982, which was the club record until 2006.

“Some managers are worth five games a year to their franchises. Sagacious moves can account for that much success. Tommy Lasorda is worth something more — a few hundred thousand in attendance,” Murray wrote in 1988.

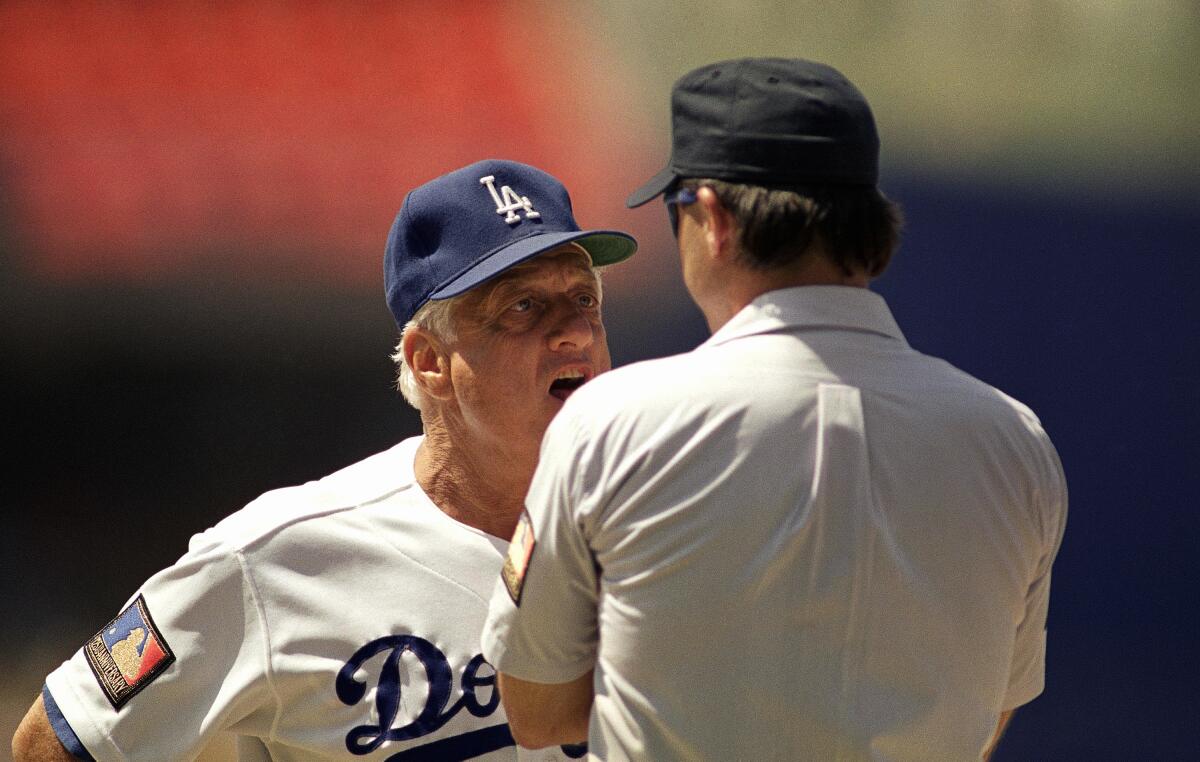

But Lasorda’s colorful personality sometimes strayed off-course.

During the 1977 World Series, he agreed to wear a microphone for enhanced TV coverage. After the New York Yankees got three straight hits off Dodgers pitcher Doug Rau in Game 4, Lasorda went to the mound and confronted Rau and the two went at it in an expletive-filled conversation that — while it never made it onto air — later became a favorite internet sound bite. How much of it was a genuine display of temper, and how much was contrived by Lasorda to give the reliever in the bullpen time to loosen up is a matter of debate.

Lasorda ran afoul of a microphone the following season, too. Asked what he thought of Dave Kingman’s three home-run performance for the Chicago Cubs in defeating the Dodgers, Lasorda exploded in an obscenity-laced tirade that lives on in transcripts and on the web.

It was all part of Lasorda’s style. He’d love his players one minute and curse them the next.

Lasorda told The Times in 1999 that he had brought “a whole new philosophy of managing” when he succeeded Alston.

“I wanted my players to be proud of the organization and I wanted them to be proud of the uniform they were wearing,” he said. “I used to tell them say thank you to the fans. If it weren’t for those people, we wouldn’t be doing what we’re doing. You have to show your appreciation.”

He won National League pennants in his first two full seasons, 1977 and 1978. Both years, the Dodgers lost the World Series to the Yankees.

They returned to the World Series in the strike-torn 1981 season, the year rookie pitching sensation Fernando Valenzuela took the baseball world by storm and touched off “Fernandomania.”

They lost the first two games of the World Series to the Yankees but swept the last four games, winning the franchise’s fifth championship and first since 1965.

Lasorda was blessed with a prolific farm system that produced four consecutive rookie-of-the-year winners from 1979 through 1982, in pitchers Valenzuela, Rick Sutcliffe and Steve Howe and second baseman Steve Sax. A young Dodgers team in 1983 won 91 games and captured the National League West but lost to the Phillies in the league championship series.

After missing the playoffs in 1984, the 1985 team won 95 games to finish first in the division. The Dodgers, matched up against the St. Louis Cardinals in the NL championship series, were on the brink of elimination and clinging to a 5-4 lead in the top of the ninth with two outs when Jack Clark stepped to the plate with runners on second and third.

Clark, a much-feared right-handed hitter, was batting .381 in the playoffs; on deck was Andy Van Slyke, who was batting .091. With first base open, logic dictated that Lasorda would tell reliever Tom Niedenfuer to walk Clark and face Van Slyke, or pull Niedenfuer and bring in left-hander Jerry Reuss. The Dodgers had intentionally walked Clark three times in the series.

But Lasorda kept Niedenfuer in the game and the move backfired spectacularly when Clark hit a fastball into the left-field stands for a three-run home run that put the Cardinals ahead to stay and launched them into the World Series.

“I feel like jumping off the nearest bridge,” Lasorda said later.

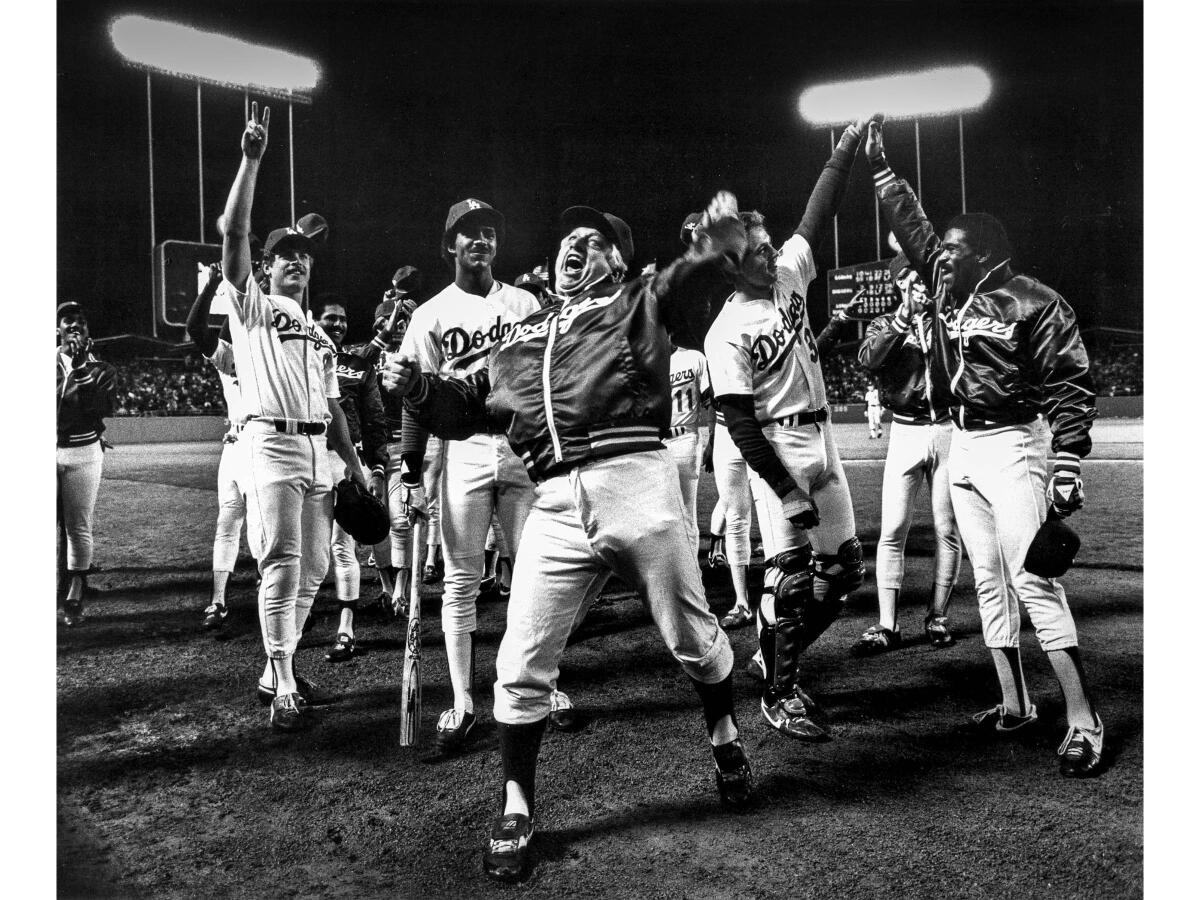

Even after discounting Lasorda’s gift for hyperbole, the 1988 World Series matchup against the Oakland Athletics was something like David versus Goliath. “The first time the underdog won,” Lasorda said.

These Dodgers weren’t expected to do much that season, and by the end, they were patched together with athletic tape and hope. Mostly, they rode the arm of Cy Young award-winning pitcher Orel Hershiser, who had set a record by pitching 59 consecutive scoreless innings. Despite a flawed lineup, they finished atop the NL West and upset the New York Mets in a seven-game NL championship series.

In the World Series, outfielder Kirk Gibson spent most of the first game getting treatment in the clubhouse for his injured back. Lasorda summoned him with two out in the bottom of the ninth, a runner on base and the Dodgers trailing, 4-3.

Facing premier closer Dennis Eckersley, Gibson slammed a slider over the right-field wall for a stirring victory that gave the Dodgers a memorable comeback. The image of Gibson pumping his right fist as he hobbled around the bases became an instant classic in Dodgers lore.

Kirk Gibson’s game-winning home run from Game 1 of the 1988 World Series.

The team went on to finish off Oakland in five games.

The 1990s were a decade of turmoil and change for Lasorda and the Dodgers.

As a favor to Lasorda, the Dodgers picked a family friend in the 62nd round of the 1988 draft, 1,390th overall. After the kid blasted a series of batting-practice pitches into the seats during a tryout, the Dodgers couldn’t find a pen fast enough.

The kid was catcher Mike Piazza, who became a Dodgers star and fan favorite before being shipped to the Florida Marlins in a hugely unpopular trade. Piazza paid tribute to Lasorda when the former catcher was enshrined in baseball’s Hall of Fame in 2016.

“Tommy Lasorda was always in my corner,” Piazza said. “He believed when he watched me hit at the young age of 14 that I could play major league baseball.”

In 1991, Lasorda’s son, Tom Jr., known as Spunky, died at 33, a death attributed to pneumonia and dehydration. Lasorda was enraged when it was widely reported that his son had died of complications of AIDS. Lasorda insisted his son wasn’t gay, though the younger Lasorda’s friends said otherwise.

“I don’t care what people ... I know what my son died of,” he told GQ magazine’s Peter Richmond in a searing portrait of father and son and a relationship that might not have been perfect but never lacked for love on both sides. “The doctor put out a report of how he died. He died of pneumonia.”

Lasorda said little publicly while his son was ill, or after his son died. He was absent from the team for only three days. His wife, Jo, said being with the Dodgers was the right place for her husband.

“There wasn’t anything else he could do at home; it was very hard for him to stay here,” she told The Times. “Like everyone, Tommy grieves in his own way, his own place, his own time.”

Jo, his wife of 70 years, survives him, as do their daughter, Laura, and a granddaughter, Emily Tess Goldberg.

After his son’s death, age seemed to creep up on Lasorda, chipping away at his cheerful veneer and slowing a man who bragged that he’d missed only seven games in all his years as a manager.

He developed tendinitis in his left shoulder and was slowed by arthritis, an ulcer and a hernia. TV cameras caught him asleep on the bench during a 1995 game, which he attributed to the side effects of his arthritis medication.

He kept going until June 1996, when he had a heart attack. He underwent an angioplasty and spent a month at home, chafing all the while. Doctors said he could return to the team July 25 but warned of the risk of further damage to his heart.

Lasorda wanted to return to the dugout to manage, but then-owner Peter O’Malley and the executive vice president at the time, Fred Claire, urged him to retire. O’Malley later said he’d left the decision up to Lasorda. Ever the good organization man, Lasorda publicly said that O’Malley had offered him the chance to return.

However, Lasorda had sensed that, perhaps, his time had passed. On July 29, with tears in his eyes and a tremor in his voice, Lasorda gave up the job he’d loved so much.

The Times invites you to share your memories of the legendary Dodgers manager.

He accepted a job as a vice president, with duties that were to include serving as an ambassador, an instructor to players and an advisor to management. He was succeeded as manager by Bill Russell, his onetime infielder, who learned of Lasorda’s retirement by reading it in the newspaper.

O’Malley stunned the baseball world by announcing Jan. 6, 1997, that he and his sister, Terry Seidler, would entertain offers to sell the Dodgers — severing a family connection to the team that began in 1944, when their father, Walter, joined a group that purchased 25% of the then-Brooklyn Dodgers. In May 1997, media baron Rupert Murdoch confirmed his interest in buying the franchise. Lasorda began to hope that a new regime would give him more responsibility.

When Murdoch’s Fox Entertainment Group completed its purchase of the Dodgers in March 1998, Lasorda’s fortunes revived. Bob Graziano, the club’s president, relied on Lasorda for advice during the ownership transition. And when Claire and Russell were fired as general manager and manager, respectively, Lasorda was appointed the interim general manager.

Lasorda’s tenure lasted less than a full season before he was replaced by Kevin Malone and bumped upstairs to senior vice president.

But he did get a chance to put on a uniform again, when he was named manager of the U.S. Olympic team for the 2000 Sydney Games. Lasorda’s team was mainly college kids and minor leaguers, but he approached the job with the same zest as if he’d been given a team of major league all-stars.

“I told them, ‘When this thing is all over, the whole world is going to know who you are. We’re going to win,’” Lasorda recalled in an interview with Baseball Digest.

And they did, defeating a favored Cuban team that had been 25-1 in Olympic competition.

Fox sold the Dodgers in 2004 to Frank McCourt, a Boston real estate developer, and his wife, Jamie. Lasorda survived that change of ownership, too, becoming an advisor. He also continued his whirlwind speaking schedule, traveling around the world to promote baseball as he got deep into his 80s and as the ownership of the Dodgers passed into the hands of Guggenheim Baseball Management, headed by Walter, in 2012. Lasorda continued to receive warm ovations at Dodger Stadium when he was frequently shown on the stadium’s video board.

In 2017, Lasorda — at the age of 90 — was asked to throw out the first pitch at Dodger Stadium in the opening game of the World Series, between the Dodgers and the Houston Astros. It marked the first time the team had returned to the fall classic since Lasorda’s squad in 1988. The team returned to the World Series again in 2018 and finally won it all in 2020, a season dramatically altered by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I wanted to die a Dodger,” he said. “I love the Dodgers so much.”

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.