Baseball world remembers Dodgers legend Tommy Lasorda through stories

- Share via

Fifteen minutes before first pitch, Tommy Lasorda disappeared.

It was 2009, and Lasorda had accompanied then-Dodgers general manager Ned Colletti to watch the organization’s double-A team in Chattanooga, Tenn. As the two walked the ballpark concourse, however, Lasorda suddenly slipped away.

“I’m looking for Tommy,” Colletti recalled Friday, “and I can’t find him.”

Colletti could have guessed where he went. Lasorda was in his 80s and more than a decade removed from his Hall of Fame career managing the Dodgers. But he still felt compelled to walk into a clubhouse and deliver a rousing pregame speech.

“You guys gotta pull on one side of the rope!”

“You’re all in this together, there’s no team like our team!”

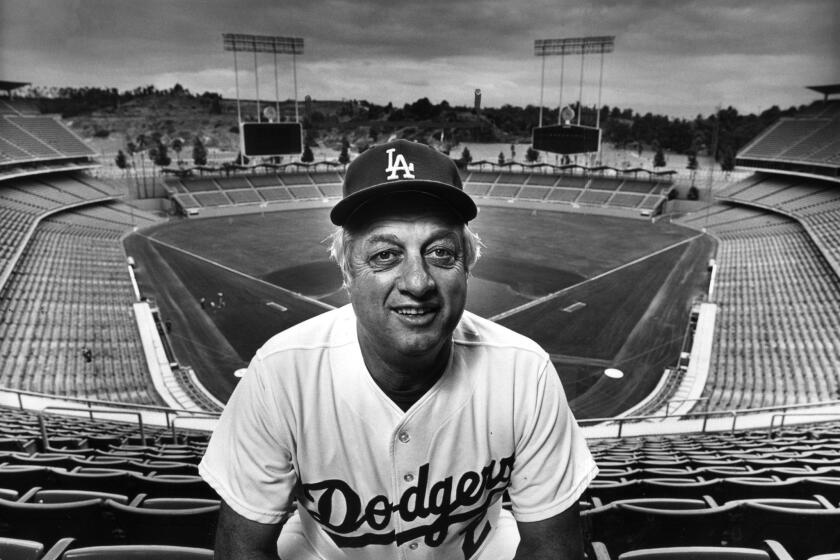

Tommy Lasorda, who won two World Series championships in 20 years as Dodgers manager, died Thursday night of a heart attack after a long illness.

“You play for the name on the front of the jerseys, not the name on the back!”

There was only one problem. “A guy taps him on the shoulder,” Colletti said, “and says, ‘Tommy, your team’s in the other clubhouse.’”

Not that it really mattered. This was Tommy Lasorda after all. And whether he was commanding the top dugout step during the World Series, or motivating the wrong minor league team, he hardly ever changed. His connection to baseball was eternal. His passion for the game was enduring.

As news of Lasorda’s death of a heart attack at age 93 spread throughout baseball, memories of his legendary life rushed to the surface. So many people had crossed paths with Lasorda during his 70-plus years in the sport. And they almost all had a story to tell.

::

Rick Monday was 17 years old when in 1963 he first met Lasorda. A recently retired pitcher working as a scout for the Dodgers, Lasorda was coaching a team of Southern California prospects that, in a pre-draft era, the team hoped to sign.

Batting second in one game, Monday watched the leadoff hitter walk on four pitches. He came to the plate planning not to swing. But from third base, Lasorda called for a hit and run.

“I have to swing and the pitch is about chin high,” Monday said. “I reach up, I hit it, and I hit it out.”

As Monday rounded the bases, he expected to get a handshake or back pat from Lasorda. Instead, Lasorda walked away in apparent disgust. Years later, when Monday was traded to the Lasorda-led Dodgers in 1977, he asked the manager why.

“There were 12 major league scouts [from teams other than the Dodgers] in the stands,” Lasorda said. “I wanted you to swing at a pitch out of the strike zone so scouts would think you had no discipline. I was irritated because you not only hit it, you hit a home run!”

That fierce competitiveness underscored Lasorda’s entire coaching career.

When former Dodger and major league manager Bobby Valentine played on one of Lasorda’s minor league teams in the late 1960s, “he had us write letters to the big league player that was playing our position,” Valentine told MLB Network, “to tell them to get ready to move over because we were on our way.”

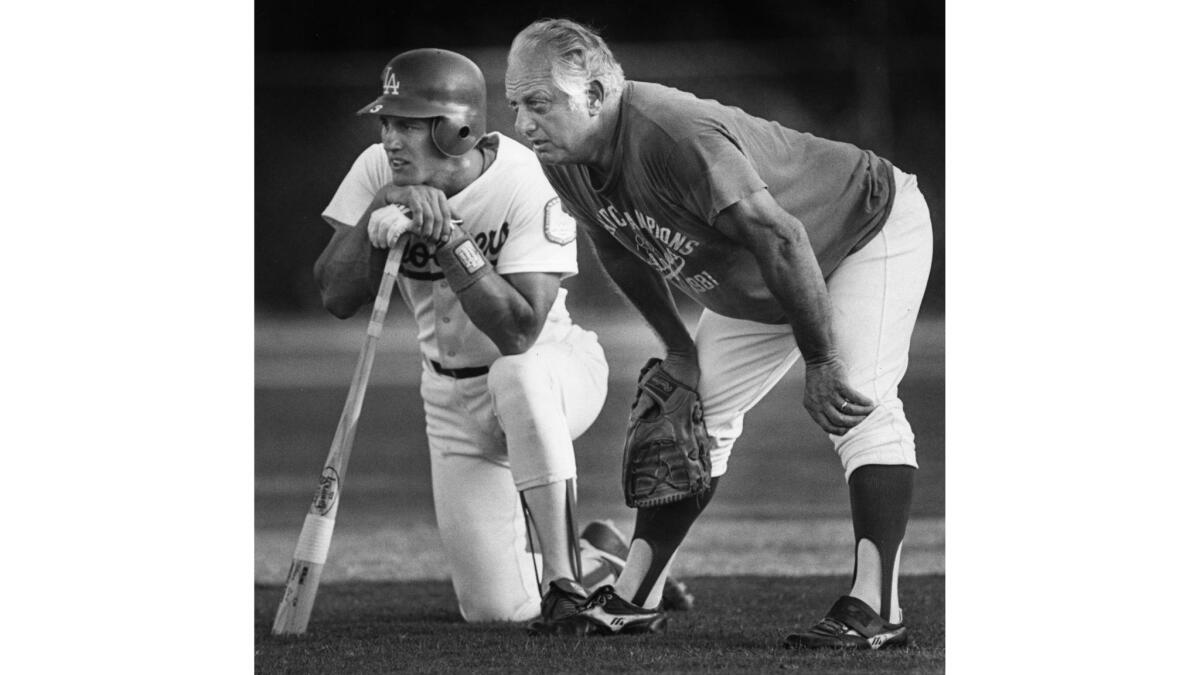

During his 20-year run managing the Dodgers, Lasorda’s mound visits became legendary — “We had a lot of banter out there,” former Dodgers pitcher Orel Hershiser recalled, “especially a fiery guy like that” — as did the days Lasorda would throw hundreds of batting practices pitches.

“Between every pitch, there was a line of motivation: ‘You can do this! You can hit it! I’ll beat your butt, you try to beat my butt!’” Valentine said. “It was always a competition.”

Dodgers manager Dave Roberts encountered something similar while playing for the team in the early 2000s, when a then-retired Lasorda once kept him in the cage for an extra 45 minutes. “I was exhausted,” Roberts said. “But hey man, this guy is a legend and you do what Tommy says. It’s one of those things that, if he’s there, he’s ready to work and he’s not going to mince words.”

Tommy Lasorda, who died Thursday night of a heart attack at age 93, bled Dodger Blue nearly his entire life, spilling it across every corner of the world.

Lasorda had a lighter touch too.

When Dodgers second baseman Steve Sax struggled with throwing yips early in his career, Lasorda kept the infielder in the lineup until his defense returned to form.

“Had it not been for Tommy Lasorda, who knows what would have happened to me,” Sax told MLB Network. “Tommy knew what it was like to be on the softer side of things. He knew about peoples’ feelings. And he knew that I was going to battle through this if I was just given an opportunity.”

::

Lasorda was the biological father to two children, Laura and Tom Jr. But he was the patriarch of a family too extensive to number precisely.

Members of the extended clan include longtime Dodger outfielder, coach and broadcaster Manny Mota and his eight children. José Mota, a former player and current Angels broadcaster, thought of Lasorda as “a big grandpa to all of us.”

The summer before he was due to begin playing at Cal State Fullerton, Mota staged a workout in front of legendary college coach Augie Garrido at Dodger Stadium. After taking ground balls from his father, then the Dodgers’ hitting coach, Lasorda emerged from the dugout in a cutoff Dodger blue t-shirt and rolled-up pants.

“Hey Manny,” Lasorda shouted. “Give me that fungo. I’m gonna get the kid that scholarship right away.”

Lasorda commandeered the session, hitting ground balls, fielding throws at first base and throwing batting practice.

A look at the life of legendary Dodgers manager Tommy Lasorda, who died at the age of 93 on Thursday.

“Augie Garrido could not stop laughing,” Mota said. “Tommy made me look good in that workout.”

Lasorda’s kindness extended even to those who never played professionally. Perry Minasian, the Angels’ first-year general manager, had a strong bond with Lasorda because the manager was the best friend of Minasian’s paternal grandfather, Edward, and was very close to Minasian’s father, Zack. When Lasorda was hired to his first managerial job in the Dodgers organization in 1966, Lasorda asked a teenage Zack to run the clubhouse at rookie-level Ogden (Utah). Zack later became a major-league clubhouse manager for the Texas Rangers, a job that spawned lifelong baseball careers for three of his four sons.

“If it wasn’t for Tommy, I wouldn’t be where I am,” Minasian said.

Lasorda’s presence in Minasian’s life was steadfast. Not even when he landed in the hospital last fall did his support waver. When Minasian was named the Angels general manager in November, Zack delivered the news to Lasorda over a FaceTime call set up by Lasorda’s daughter.

“They said he lit up,” Minasian said.

Hershiser also felt that fatherly connection over 12 seasons with Lasorda’s Dodgers. When the rookie pitcher failed to make the Dodgers’ 1983 opening day roster, Lasorda consoled him while he packed his bags. After Hershiser struggled early the next season, Lasorda bestowed him with his iconic “Bulldog” nickname.

“There was never a moment in my Dodger career that Tommy Lasorda wasn’t by my side … developing my confidence and my belief in myself,” Hershiser said. “Tommy found that in me and grew it.”

Once Hershiser joined the Cleveland Indians in 1995, his communication with Lasorda slowed — until he received a letter from the manager.

“He wrote me a whole two or three pages about our father-son relationship and how he felt a distance, and we needed to rekindle it,” Hershiser said. “He really was telling me that just because you’re wearing another uniform, our relationship’s not going to stop.”

::

When Valentine managed the 2001 National League All-Star team, he invited Lasorda to be a ceremonial guest coach. With the NL trailing in the sixth inning, however, Lasorda concocted a grander idea.

“Hey Bobby, you need some runs,” Lasorda said. “Put me out on third.”

Valentine relented and made Lasorda a base coach. When Vladimir Guerrero lost the grasp of his bat during a swing, Lasorda tumbled on his back to avoid getting hit.

“He’s doing a back roll,” Valentine said, “and I had my heart in my hands.”

Lasorda simply stood up, smiled and received a standing ovation from the crowd at Seattle’s Safeco Field. “I’m going to be 74 in a couple months,” he said after the game. “I’m just not as agile as I used to be.”

Remembering late Dodgers legend Tommy Lasorda at his unfiltered finest, including his feelings about Dave Kingman hitting three home runs against L.A.

There wasn’t much else Lasorda lost with age.

During a Dodgers road trip to then-general manager Dan Evans’ native Chicago in 2002, a friend who owned a local restaurant arranged a postgame party in Evans’ honor with friends and family.

“Early in the night, there’s this commotion at the front door, and there’s Tommy,” Evans said. “I said, ‘What’s going on?’ He said, ‘I heard about this party, and I came up to have some fun and meet your friends and family— I wouldn’t miss this for the world.’”

Lasorda proceeded to the kitchen, where he spent “a solid hour” regaling the staff with stories and eating. Then he came into the dining room to shoot pool and mingle with guests. He was one of the last to leave.

“The next day, my friend who owns the restaurant called and told me Tommy took pictures with everyone on the staff,” Evans said. “He hung out with everybody in the kitchen. He’s larger than life.”

Former Dodgers vice president of communications Derrick Hall, now president and chief executive officer of the Arizona Diamondbacks, always marveled at how fans flocked to Lasorda — and how he thrived in hostile environments.

Whenever the Dodgers played the hated San Francisco Giants in old Candlestick Park, Hall made a point of walking with Lasorda from the team’s right-field clubhouse onto the field for batting practice.

“The fans would start booing him, and pretty soon the entire crowd would catch on and start booing,” Hall said. “Tommy would start blowing kisses and bowing and they were throwing stuff at him, and he just ate it up. He loved it.”

After Colletti, a former Giants assistant general manager, was hired by the Dodgers in 2005, he showed up to spring training wearing the National League championship ring he’d won in San Francisco three years earlier, “just to inspire a little bit of fierceness in the group,” Colletti said.

Lasorda noticed. Two days in, he pulled Colletti aside.

Tommy Lasorda has died at 93. The Times invites you to share your memories of the legendary Dodgers manager.

“You know I love you, and I’m glad that you’re with us, and this is gonna be great for everybody,” Lasorda said. “One thing, if you wear that ring again tomorrow, your hand will be missing.”

It was vintage Lasorda — brutally blunt and refreshingly honest, competitiveness and compassion that remained intertwined for the rest of his days.

“He could make you laugh. He could motivate you. He could bring you confidence. He could question something to get you to think differently. And he could love you,” Colletti said. “He could do all of that in about five minutes.”

::

The last year had been one of Lasorda’s hardest. The COVID-19 pandemic prevented him from entering the Dodger Stadium clubhouse or hanging around his second family at Chavez Ravine. He couldn’t see many of his friends or former players in person, resorting to FaceTime and video calls instead.

And while he still carried on conversations, his once boundless energy would wane.

“He was with us and sharp for 15 to 30 minutes and then slowly you could tell that things were starting to shut down a little bit,” Hershiser said.

What didn’t go away was Lasorda’s desperate desire to see the Dodgers win the World Series again.

“I kind of made a promise to him that we would win it before he left us,” Roberts said. “And he said that he was gonna stick around long enough to see.”

Tommy Lasorda, who died Thursday at age 93, viewed his accomplishments across 71 years with the Dodgers through an unconventional lens.

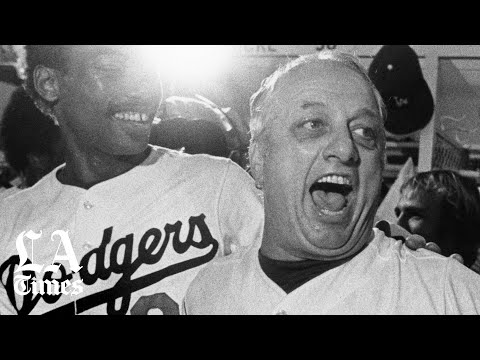

So, for Game 6 of the World Series, Lasorda flew to Globe Life Field in Arlington, Texas, to witness them win it all. He watched from a suite with Valentine and former Dodgers pitching coach Rick Honeycutt, then found Roberts at the end of the night to share a joyful and teary embrace.

“Just elation,” Roberts said. “It wouldn’t have been complete if he weren’t there.”

Weeks later, Lasorda was hospitalized and spent much of the next two months in the intensive care unit. He was finally able to go home Tuesday, two days before he suffered his fatal heart attack.

“He willed himself to live this long and to watch that world championship,” Hershiser said. “He willed himself to stay active with baseball and to be impactful on a daily basis. There were no boundaries to something positive, something about winning that he could do. He made it a lot farther than a lot of us would. I hope we live that full a life.”

Times sports columnist Dylan Hernández contributed to this report.

More to Read

Are you a true-blue fan?

Get our Dodgers Dugout newsletter for insights, news and much more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.