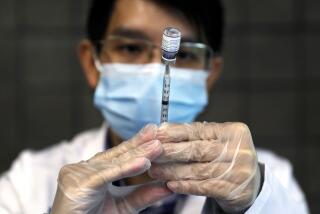

One year of vaccines: Many lives saved, many needlessly lost

- Share via

One year ago, the biggest vaccination drive in American history began with a flush of excitement in an otherwise gloomy December. Trucks loaded with freezer-packed vials of a COVID-19 vaccine that had proved wildly successful in clinical trials fanned out across the land, bringing shots that many hoped would spell the end of the crisis.

That hasn’t happened. A year later, too many Americans remain unvaccinated and too many are dying.

The nation’s COVID-19 death toll is just shy of 800,000 as the anniversary of the U.S. vaccine rollout arrives. A year ago, it stood at 300,000. An untold number of lives — perhaps tens of thousands — have been saved by vaccination. But what might have been a time to celebrate a scientific achievement is fraught with discord and mourning.

Dr. Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, said scientists and health officials may have underestimated how the spread of misinformation could hobble the “astounding achievement” of the vaccines.

“Deaths continue ... most of them unvaccinated, most of the unvaccinated because somebody somewhere fed them information that was categorically wrong and dangerous,” Collins said.

Developed and rolled out at blistering speed, the vaccines have proved incredibly safe and highly effective at preventing deaths and hospitalizations. Unvaccinated people have a 14 times higher risk of dying compared with fully vaccinated people, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated based on available data from September.

Their effectiveness has held up for the most part, allowing schools to reopen, restaurants to welcome diners and families to gather for the holidays. At last count, 95% of Americans 65 and older had had at least one shot.

In a large study, the risk of a breakthrough infection was 10 times lower for people who got a COVID-19 booster shot than for people who hadn’t.

“In terms of scientific, public health and logistical achievements, this is in the same category as putting a man on the moon,” said Dr. David Dowdy, an infectious disease epidemiologist at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The vaccines’ first year has been rocky with the disappointment of breakthrough infections, the political strife over mandates and, now, worries about whether the Omicron variant will evade protection.

Despite all that, Dowdy said, “we’re going to look back and say the vaccines were a huge success story.”

On the very day that an eager nation began rolling up its sleeves, Dec. 14, 2020, the U.S. death toll from COVID-19 hit 300,000. And deaths were running at an average of more than 2,500 a day and rising fast, worse than what the country witnessed during the harrowing spring of 2020, when New York City was the epicenter of the U.S. outbreak.

By late February, total U.S. deaths had crossed 500,000, but the daily death count was plummeting from the horrible heights of early January. With hopes rising in early March, some states began reopening, lifting mask mandates and limits on indoor dining. Former President Trump assured his supporters during a Fox News interview that the vaccine was safe and urged them to get it.

But by June, with the threat from COVID-19 seemingly fading, demand for vaccines had slipped and states and companies had turned to incentives to try to restore interest in vaccination.

With immunity waning and the Omicron variant looming, many scientists are saying the definition of ‘fully vaccinated’ should include a booster shot.

It was too little, too late. Delta, a highly contagious coronavirus variant, had silently arrived and had begun to spread quickly, finding plenty of unvaccinated victims.

“You have to be almost perfect almost all the time to beat this virus,” said Andrew Noymer, a public health professor at UC Irvine. “The vaccine alone is not causing the pandemic to crash back to Earth.”

One of the great missed opportunities of the COVID-19 pandemic is the shunning of vaccination by many Americans.

This fall, Rachel McKibbens, 45, lost her father and brother to COVID-19. Both had refused the protection of vaccination because they believed false conspiracy theories that the shots contained poison.

“What an embarrassment of a tragedy,” McKibbens said. “It didn’t have to be this way.”

Persistent myths about COVID-19 vaccine safety are hobbling efforts to promote the shots in certain parts of California, officials say.

More than 228,500 Americans have died from COVID-19 since April 19, the date when all U.S. adults became eligible to be vaccinated. That’s about 29% of the total since the first U.S. coronavirus deaths were recorded in February 2020, according to an Associated Press analysis.

Two states — Florida and Texas — have contributed more than 52,000 deaths since that date. Alaska, Hawaii, Oregon, Wyoming and Idaho also saw outsize death tolls after mid-April.

Red states were more likely than blue states to have greater than average death tolls since then.

“I see the U.S. as being in camps,” Noymer said. “The vaccines have become a litmus test for trust in government.”

Wyoming and West Virginia, the states with the highest vote percentages for Donald Trump in 2016, have recorded about 50% of their total COVID-19 deaths since all adults were declared eligible for the vaccine in those states. In Oklahoma, nearly 60% of COVID-19 deaths occurred after all adults became vaccine-eligible.

In the five states with the lowest levels of vaccination, the COVID-19 death rate this summer was more than triple the rate in the five states where vaccination is most common.

There are exceptions: Notably, Hawaii and Oregon are the only Joe Biden-supporting states where more than half of the COVID-19 deaths came after shots were thrown open to all adults. North Dakota and South Dakota — both ardent Trump states — have kept their share of deaths after the vaccine became available across the board to under 25%.

California has seen more than 15,000 COVID-19 deaths since the state opened eligibility to all adults in mid-April. McKibbens’ father and brother died in Santa Ana, in their shared home.

McKibbens pieced together what happened from text messages on her brother’s phone. Some of the texts she read after his death, including back-and-forth messages with a cousin who cited TikTok as the source of bad advice.

“My brother did not seek medical attention for my dad,” keeping him lying on his back, even as his breathing began to sound like a broken-down motor, said McKibbens, who lives across the country in Rochester, N.Y.

Her father, Pete Camacho, died Oct. 22 at age 67. McKibbens flew to California to help with arrangements.

Her brother was sick too, but “he refused to let me into the house because he said I shed coronavirus because I was vaccinated,” McKibbens recalled. “It was a strange new belief I had never heard before.”

Fear of the unknown and disinformation, fueled largely by social media, are the main culprits in a large swath of land already lacking in sufficient resources.

A friend found her brother’s body after noticing food deliveries untouched on the porch. Peter Camacho, named for his father, died Nov. 8 at age 44.

“For me to have lost two-thirds of my family, it just levels you,” McKibbens said.

Important advice came too late for some. Seven months pregnant and unvaccinated, Tamara Alves Rodriguez tested positive for the coronavirus Aug. 9. Two days later, with many pregnant women falling seriously ill, U.S. health officials strengthened their guidance to urge all mothers-to-be to be vaccinated.

Rodriguez had tried to get a vaccination weeks earlier but was told at a pharmacy she needed authorization from her doctor. “She never returned,” said her sister, Tanya Alves of Weston, Fla.

Six days after testing positive, Rodriguez had to have a breathing tube inserted down her throat at a hospital near her home in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Her baby girl was delivered by emergency caesarean section Aug. 16.

The young mother never held her child. Rodriguez died Oct. 30 at age 24. She left behind her husband, two other children and an extended family.

A long-standing tradition of keeping pregnant women out of clinical trials is having serious consequences with regard to COVID-19.

“Her children ask for her constantly,” Alves said. “I literally feel like a piece of me has been ripped out of me and even those words aren’t enough to describe it.”

She urges others to be vaccinated: “If you would know the terror of being hospitalized or having a loved one there ... if people would know, they would be afraid of this instead of fearing the vaccine.”

AP data journalist Angeliki Kastanis and AP medical writer Lauran Neergaard contributed to this report.