Should the definition of ‘fully vaccinated’ be changed to include a booster shot?

- Share via

For many Americans who scrambled to get vaccinated against COVID-19 as soon as their turn came up, the relief of gaining immunity was just one reward. Achieving “fully vaccinated” status conferred a faint halo of virtue as well.

Now, both the shots’ biological protection and the satisfaction of contributing to the herd’s immunity are proving short-lived. And with a worrisome new coronavirus variant threatening to erode vaccine-induced immunity further, health officials are debating whether the definition of “fully vaccinated” should be amended to include a booster shot.

Scientists are leaning heavily in favor, and public health leaders are not far behind.

So far, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention hasn’t officially shifted the goalposts. Americans subject to job-related vaccine mandates or required to show proof of “full vaccination” to enter gyms, restaurants or public events can satisfy the requirement without a booster.

But the CDC has tiptoed up to those goalposts, telling all but the youngest vaccinated Americans that durable immunity will require an extra dose, and urging everyone 16 and older to get one as soon as they are eligible.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, President Biden’s senior advisor on the pandemic, also walked right up to the line — but didn’t cross it.

“Optimal protection is going to be with a third shot,” Fauci told CNN this week. He added that while he didn’t see the official definition of “fully vaccinated” changing this week or next, it was bound to happen at some point: “It’s going to be a matter of when, not if.”

The number of fully vaccinated Americans, under the current definition, passed the 200 million mark this week, and a quarter of them have gotten a booster. That leaves millions of Americans with another to-do item on their list, asking whether they’ll be better off if they get one, and wondering whether it will be the last.

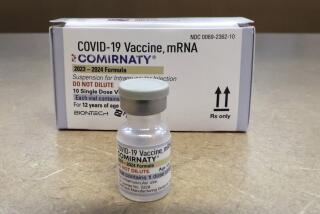

Their confusion is understandable. The vaccines’ early promise of spectacular effectiveness has given way to some gloomy headlines about waning immunity. But the CDC has continued to assert that for most healthy Americans, “full vaccination” — two jabs of the Pfizer-BioNTech or Moderna vaccine or a single Johnson & Johnson shot — provides powerful protection against hospitalization or death in those with “breakthrough” infections.

A study of 780,000 veterans shows a dramatic decline in effectiveness for all three COVID-19 vaccines in use in the U.S.

Until recently, independent vaccine experts seemed ambivalent too. In September and October, advisors to the CDC and the Food and Drug Administration who reviewed the latest evidence were distinctly underwhelmed by the case made for recommending boosters for healthy adults under 65.

They endorsed the extra shots wholeheartedly for older Americans and people with compromised immune systems. But many were unwilling to conclude that younger adults would benefit from a booster, especially considering the risk of heart-related side effects that mostly affect younger males and blood clotting risks for women under 50.

Their vote to limit access was promptly overruled by the CDC, which recommended boosters for virtually all adults once six months had passed since their second dose of one of the two mRNA vaccines or two months had passed since their J&J shot.

Now, said Dr. William Schaffner, an infectious disease specialist at Vanderbilt University Medical School, experts who had doubts are abandoning their qualms.

For starters, he said, sending different messages to different age and occupation groups had proved too confusing. Plus, new research has made it increasingly clear that the first two doses of an mRNA vaccine and the single shot of the J&J vaccine, behave like a single “prime” dose that requires a follow-up “boost” to reach its full effect.

As with most vaccines, a COVID-19 booster will be required to shore up immunity and make it last. And there’s precedent for a three-dose series, he noted. Widely administered vaccines for hepatitis B, polio and other diseases require three or more shots.

Approving COVID-19 booster shots seemed like a slam dunk, but two influential advisory boards raised a host of complicated questions.

Dr. Peter Hotez, dean of Baylor College of Medicine’s National School of Tropical Medicine, agreed: “From the beginning, I’ve said this is a three-dose vaccine.”

Given the sense of urgency that prevailed when vaccines first became available, it made sense to space the first and second doses of mRNA vaccine close together, Hotez said. “But based on previous experience with vaccines, we know that’s going to result in waning immunity. And you’ll need a third dose some time later.”

By summer, the rising incidence of breakthrough infections offered growing support for that surmise. Most of the initial cases were in older and immunocompromised people, who frequently don’t mount a strong immune response to vaccines. Many experts hoped the need for boosters would end there.

But evidence of waning immunity from all vaccines, and across the age spectrum, is growing. Even fully vaccinated younger adults with breakthrough infections can become severely ill and die.

This week brought the first real-world evidence of boosters’ benefits in young, healthy people. Israeli researchers found that a third dose of the Pfizer vaccine prevented infections more dramatically in 16- to 29-year-olds than in any other age group measured. Given the key role of young adults in sustaining pandemic spread, some scientists suggested a policy of universal boosters could do more than reduce hospitalizations and deaths. It might also suppress new waves of infections.

That and another new study from Israel also shored up evidence of boosters’ powerful benefit for middle-age adults. Israelis 50 and over who got a third shot were 10 times less likely to die of COVID-19 than their vaccinated-but-unboosted peers. Israelis 60 and over reduced their risk of severe illness by a factor of more than 12 compared with their counterparts who didn’t get a third shot, and they were almost 15 times less likely to die of COVID-19.

In a large study, the risk of a breakthrough infection was 10 times lower for people who got a COVID-19 booster shot than for people who hadn’t.

Los Angeles County has provided further evidence of boosters’ impact. For the seven-day period that ended Nov. 29, there were 43 new infections for every 100,000 residents who were fully vaccinated but not boosted. But among those who did get a booster, the rate of new infections was just 7 per 100,000.

For now, Hotez said, communicating clearly to those 16 and up that they should get booster shots for their own protection is more important than changing the definition of “fully vaccinated” — something that would affect everyday life in cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco that require proof of vaccination to enter indoor businesses like restaurants and gyms.

As health officials grapple with the pandemic’s next move, he said, they may decide that reducing COVID-19 deaths and keeping people out of the hospital are the most urgent priorities. That would dictate a greater focus on increasing rates of initial vaccinations over boosters.

But if case rates begin to recede, emphasizing boosters might be a way to slow transmission and end the pandemic sooner — and changing the definition of fully vaccinated may well support such a goal, Hotez said.

Some experts remain skeptical that taking that step would make sense. They ask whether it is ethical and productive to offer extra doses to those least likely to become very ill when many of the world’s poorest countries have barely begun vaccinating their populations.

In people who got a booster shot, levels of neutralizing antibodies exceeded the peak that followed two doses of COVID-19 vaccine.

The new findings from Israel clearly show that booster shots are valuable to people 50 and older, said Dr. Emily P. Hyle, an infectious disease specialist at Massachusetts General Hospital. But “it gets a little trickier” to conclude that they’re useful for younger people, she added.

“I’m looking for more granular data on what type of symptoms they’re preventing. Is it a day of sniffles or a week or two of significant illness?” Hyle said. “That’ll be really helpful to know.”

The answer could inform a fuller debate on whether getting more Americans — or the rest of the world — their initial doses of vaccine is a more effective use of scarce resources, she said. That, in turn, should also spark “some tough conversations” about the goals U.S. health officials should shoot for: to stamp out transmissions altogether, minimize severe illness and deaths, or return to pre-pandemic life without public health strictures.

Hotez said it’s possible a fourth shot — or more — will be needed. That will depend on a host of unknowns beyond the human immune system’s response to boosters, including the emergence of variants that erode vaccine protection, and the priorities of health leaders.

“We don’t know till we know,” he said.