- Share via

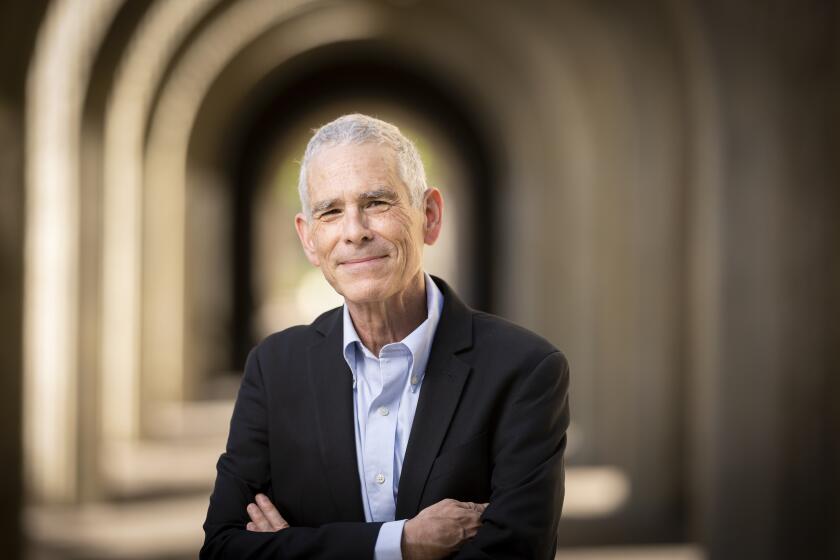

George Hodgin, chief executive of Biopharmaceutical Research Co., stands inside the room where marijuana is being grown near Monterey for federally approved drug trials. The goal is an entirely new generation of medical marijuana that is scientifically tested and dispensed with the oversight and precision of conventional pharmaceuticals.

- Share via

PHOENIX — The horrific ride to the top of the San Francisco skyscraper is still seared in Paul Scott’s memory a quarter-century later.

On a sales call for the elevator company that employed him in the mid-1990s, Scott stepped out at the penthouse level to find all the exits to the outside bolted shut — meant to deter desperate AIDS victims in a city gripped by a public health crisis.

Some were jumping to their deaths.

“Back then, there was nothing the doctors could do for you,” said Scott, 58, who would later contract HIV himself. “The drugs they had were worse than the disease.”

Marijuana was one of the rare things that could bring relief — if patients could get it.

Scott would enlist in a legalization crusade that would take him from the defiant San Francisco Cannabis Buyer’s Club to opening his own dispensary — Southern California’s first — in Inglewood. Along the way, he joined a loose affiliation of chronically ill patients and cannabis culture icons who would use California as a springboard to reshape drug policy nationwide.

Their efforts propelled the passage of the nation’s first medical marijuana law 25 years ago this week. California’s Proposition 215, titled the Compassionate Use Act, put the state in uncharted territory and set in motion a historic cultural shift throughout the country.

Subscriber Exclusive

Subscribers get early access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers first access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

The activists who championed the measure could not have anticipated it would lay the groundwork for a multibillion-dollar legal cannabis market, with boutique pot shops sprouting alongside cafes and grocery stores around the country, and venture capitalists clamoring to invest in the industry.

“If we had lost back then, it is highly unlikely that Colorado and Washington would have legalized marijuana for all adults in 2012 or that we’d now be talking about the inevitability of marijuana being legal across the country,” said Ethan Nadelmann, who helped lead the 1996 California campaign and persuaded George Soros and other ultrawealthy philanthro-pists to donate the millions of dollars crucial for victory.

Today’s landscape of marijuana lounges and unfettered access to cannabis cartridges and candies hardly resembles those chaotic early years of legalization, when the Clinton administration threatened to revoke doctors’ medical licenses and federal drug agents in helicopters terrorized California growers. Pot is now legal for medical use in 36 states and recreational use in 20.

Yet the enduring federal prohibition of the drug continues to undermine scientists eager to put it to use bringing comfort to the chronically ill people in whose name the legalization movement was launched.

“I think all of us are mystified that we have so many states where it’s legal, and yet it feels like we’re still being impeded every step of the way,” said Dr. Sue Sisley, an Arizona psychiatrist and one of the nation’s leading researchers studying marijuana to treat veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. “We still don’t have a clue how to guide patients on this. We are guessing.”

Researchers eager to conduct rigorous scientific studies have hit daunting roadblocks that come with a substance still classified by Washington as more dangerous than cocaine and opium and as having no medical value — even as millions use it to treat ailments. Yet, as with so many other things California does, advances by the state that long infuriated federal regulators are becoming their guideposts. After a quarter-century in which California fought the status quo, launching marijuana research at its universities years before others took that plunge, it is Washington that has become the outlier.

Now, medical researchers long stymied by Washington’s “Reefer Madness” mindset are being freed by the Biden administration to attempt to develop medical marijuana that is scientifically tested and dispensed with the oversight and precision of conventional pharmaceuticals.

Sisley’s grass-roots operation in Phoenix and a more commercial startup on California’s Central Coast have been given something historic: federal licenses to cultivate pot. Both operations aim to develop medicines the Food and Drug Administration will ultimately authorize for sale in pharmacies, where they will be covered by medical insurance.

No state has had a bigger impact on the direction of the United States than California, a prolific incubator and exporter of outside-the-box policies and ideas. This occasional series examines what that has meant for the state and the country, and how far Washington is willing to go to spread California’s agenda as the state’s own struggles threaten its standing as the nation’s think tank.

For more than 50 years, the only marijuana permitted for use in research has been grown at a federal facility at the University of Mississippi, where advocates say the product more closely resembles weak 1980s dime-bag marijuana than what is available at thousands of dispensaries today. “You could not even sell some of that stuff if you wanted to,” said Antonio Frazier, a cannabis testing lab executive and board member of the advocacy group Americans for Safe Access.

Two-thousand miles away, in a Monterey-area grow room, Biopharmaceutical Research Co. founder George Hodgin showed off his fledgling crop, predicting that “these plants will serve as the foundation for the next iteration of cannabis in California and around the globe.”

Fingerprint scans are required to enter and exit the facility, which houses a $45,000 bank vault approved by the Drug Enforcement Administration to store its stash.

The target market for these growers is the mass of patients currently left to improvise. They are people like the autistic children enrolled in a study at the Center for Medicinal Cannabis at UC San Diego testing the extent to which CBD, one of the dozens of cannabinoids in marijuana plants, can control impulses and aggressive behavior.

California had a plan for the government to do your taxes for you. Tax software firms led by Intuit worked to kill it. Why it’s getting another look in Washington.

The director of the study, Dr. Doris Trauner, a pediatric neurologist, said parents she worked with were experimenting with cannabis treatments, but “nobody knew what they were doing.”

“They didn’t know what dose to use, they didn’t know where to get it, and they didn’t know whether what they were getting was really CBD,” Trauner said. Some of the products branded as pure CBD contained THC, the cannabinoid that causes the high associated with the drug. CBD is sought out by parents because it is believed to treat symptoms without any high.

“They were getting just about everything,” Trauner said. “And in a lot of cases, they were probably getting nothing, because what’s in the bottle wasn’t necessarily reflected on the label.”

Among the kids enrolled in the study is 15-year-old Decedrick Dumas. “He is extremely anxious,” said Olivia Dumas, Decedrick’s mother. “He gets overwhelmed. … He feels his emotions 10 times more than we do.”

Olivia says CBD has been life-changing for the family, helping Decedrick stay calm and focused in a way nothing else does. It is part of a pattern Trauner has seen with many of the 30 children in the study. Several of them were nonverbal when the research got underway.

“Children who weren’t speaking at all were saying a few words,” Trauner said. “One child who had never vocalized at all started singing songs.”

The CBD being administered to the children in the study comes from a pharmaceutical called Epidiolex. It is the only authorized prescription drug in the U.S. made from the cannabis plant, and it is only authorized by the FDA for patients with epilepsy.

The out-of-pocket cost for anyone else who gets a prescription runs to thousands of dollars a year, as can happen with off-label pharmaceuticals.

Such is the case with a long list of ailments that patients are already treating with marijuana, even as the science has been sidelined by federal prohibition. PTSD, epilepsy, chronic pain, bipolar disorder, insomnia, depression and Parkinson’s are among the many illnesses for which pot shows promise as an alternative to conventional drugs that can come with debilitating side effects.

Yet, said Frazier, “there is often no one available to you but a budtender to guide the treatment conversation.”

Climate credits sold to California polluters bring billions to landowners. But scientists ask if that’s an environmental investment or a Ponzi scheme.

It has exasperated the pioneers working to bring patients better research and precise dosing.

Hodgin, a former Navy SEAL, says he got into the cannabis business after a close friend suffering PTSD couldn’t get useful guidance from Veterans Affairs physicians. He recalls the years his facility sat empty while the Trump Justice Department worked to block his license.

“What was going through my mind is that 22 veterans a day kill themselves,” Hodgin said. “We can start to answer a lot of the questions about whether cannabis can help them. But we were just sitting here empty…. How many people could have been helped during that time?”

After Sisley and her allies fought the federal government in court for years over its refusal to approve pot production licenses, regulators finally broke the Mississippi monopoly in May by granting four new facilities federal licenses to grow research cannabis.

Yet the new research landscape is still laden with red tape that frustrates scientists and baffles patients.

That much is clear just trying to find the operation where Sisley’s Scottsdale Research Institute has been permitted by the Drug Enforcement Agency to cultivate and process a modest amount of marijuana.

Its location is top secret at the insistence of a DEA worried that Sisley’s humble grow will somehow become a target for cartels and other traffickers in a state where pot is already omnipresent.

The Scottsdale Research Institute and Biopharmaceutical Research Co. cultivation operations are both still in their infancy and have yet to receive authorization to supply any marijuana to scientists.

Research institutions, however, are eager to place orders.

At UCSD, for example, even studies that could help law enforcement understand the risks of pot are impeded by federal rules.

As it examines the impact of marijuana use on motorists, the university has acquired a state-of-the art driving simulator and a crop of volunteers willing to go for a virtual spin while stoned. But the university must still use the marijuana from the University of Mississippi. It is strictly forbidden from testing how any of the myriad pot products available to every adult in California impair drivers, because bringing even one gummy into the lab is a federal crime.

“I could go to jail, potentially,” said Dr. Igor Grant, a founder of the UCSD cannabis research center. But the bigger risk is the university’s financial health. “They’ve got zillions of dollars of grant funding from the feds that could be jeopardized.”

Congress has made multiple attempts to ease the federal rules. A large, bipartisan coalition of lawmakers has repeatedly approved budget language that prohibits federal law enforcement from busting pot businesses operating legally under state laws.

Yet scientists will continue to face major barriers as long as cannabis is categorized federally as a Schedule I drug, meaning it is highly addictive with no accepted medical use. Getting that changed is proving a heavier political lift, even with Senate Majority Leader Charles E. Schumer (D-N.Y.) leading the fight.

Rescheduling is a burdensome, politically fraught process. Powerful voices in Congress are fighting it, and President Biden is a tepid ally of the movement.

“Marijuana is a gateway drug,” Rep. Greg Murphy (R-N.C.), a physician, said in a floor speech when the House passed a measure to remove pot from Schedule I in December. “It undoubtedly leads to further and much more dangerous drug use.”

The measure, sponsored by Judiciary Committee Chairman Jerrold Nadler (D-N.Y.), died in the Senate.

The American Medical Assn. is also fighting Nadler’s bill, which is headed toward House approval again. The group warns there is too little research into the safety and medical implications of marijuana to merit legalization. It supports a measure Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.) co-wrote to boost research while leaving the drug on Schedule I. Feinstein has been promoting the measure since 2016, but it has yet to make it out of Congress.

“It is an insane situation,” said Dale Gieringer, director of the California chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, or NORML, and one of the lead organizers of the Proposition 215 campaign in 1996.

Marijuana, he notes, was designated a Schedule I drug during the Nixon administration, when the president ignored the findings of a commission he convened to study its dangers.

The commission concluded that marijuana was no more dangerous than alcohol. Nixon, at war with pot-smoking leftists, directed his administration to ignore those findings.

“The federal government deliberately overregulated this years ago,” Gieringer said. “And now they are having a hard time untangling their own regulations.”

The trip to this point for many California medical pot advocates has been long and strange. Ed Rosenthal, a marijuana horticulture guru and one of the organizers of the push for Proposition 215, found himself in 2003 at the center of one of the odder moments in American legal history when the jury that convicted him in a federal trial of cultivation and conspiracy turned on the judge.

Jurors had no idea Rosenthal had been granted a license by Oakland officials and deputized as an “officer of the city” to cultivate starter plants for Bay Area marijuana clubs serving seriously ill patients. Jurors learned about it only after the guilty verdict, at which point they held a news conference to pillory the U.S. District Court judge and beg Rosenthal’s forgiveness.

The trial Rosenthal described in an interview as “like the Chicago 7” was a milestone for medical marijuana.

The crackdown by federal prosecutors — which not long before had been praised by a California attorney general who warned Proposition 215 created legal anarchy — was fast falling further out of step with public opinion.

The persistence of federal prohibition to this day astonishes Rosenthal.

Yet when he, Gieringer, Nadelmann and several others who led the Proposition 215 movement gather at a California NORML event in San Francisco on Friday to celebrate legalization’s 25th anniversary, they need only look to the day’s program to see how far they have come.

The welcome remarks will be delivered by California’s attorney general.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.