- Share via

Soon after Maribel Munoz joined the trailblazing ranks of American owners of hydrogen cars — a group that exists only in California — she began to fear that the low price of the taxpayer-subsidized Toyota Mirai she purchased came with a tremendous cost.

“You can’t have a job and own this car,” said the 49-year-old clothing designer from Azusa. “Finding fuel for it becomes your job. It is constant anxiety. I told the guy at Toyota, ‘If I have a stroke, it’s on you.’”

Munoz found herself stranded with an empty tank on the highway and stressed out by the repeated fuel shortages Mirai drivers call “hydropocalypses.” She struggled not to scream at her phone after driving miles to stations that a hydrogen fueling app said were working just fine, only to find them out of order.

These are the kind of hassles that can come with being an early adopter. But in the case of California’s “Hydrogen Highway” — a network of fueling stations then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger dreamed would lure masses of Americans to hydrogen vehicles — even the most climate-conscious, tech-savvy motorists are asking: What’s the point? The Hydrogen Highway was meant to stretch from coast to coast. But after 17 years, it has yet to make it past the state line.

Environmentalists warn that the futuristic hydrogen fuel cell cars, marketed as producing zero emissions, leave an inexcusably heavy carbon footprint. The few automakers that have not backed away from the concept of powering a passenger car by splitting off electrons from hydrogen ions are struggling to persuade drivers that the vehicles are a reliable alternative to zero-emission battery-powered ones. And other states that typically look to California for climate-friendly transportation inspiration are taking a pass.

You can’t have a job and own this car. Finding fuel for it becomes your job.

— Maribel Munoz, on her hydrogen-fueled car

“It started as kind of a bad bet by the state,” said Ethan Elkind, director of the climate program at UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment. “Now it has become a legacy zombie technology.”

California can’t let go of Schwarzenegger’s vision. In 2004, he famously got behind the wheel of a clunky Hummer prototype that ran on hydrogen to signal that drivers can have it all: the excess and convenience of a gas guzzler, with none of the emissions. (It turned out that the hydrogen Hummer wasn’t so climate-friendly and never made it to commercial production.)

State officials say the hydrogen experiment is merely experiencing the growing pains of every transportation innovation California pushed into the mainstream. The Biden administration is right there alongside California, championing lucrative subsidies and demonstration projects aimed at making hydrogen fuel an affordable and truly green alternative, one that it hopes could complement the battery-powered electric vehicle market.

“Ten years ago, people would have come to me and said, ‘Why is California supporting battery vehicles? There is hardly any market, and they will never be competitive,’” said Patty Monahan, a member of the California Energy Commission. Of course, battery electric vehicles are all the rage now.

It started as kind of a bad bet by the state. Now, it has become a legacy zombie technology.

— Ethan Elkind of UC Berkeley’s Center for Law, Energy and the Environment

Monahan said the state’s aggressive push to get drivers into hydrogen cars is meant to help the technology rapidly scale up, to the point where large fleets of trucks running on diesel and aircraft powered by jet fuel could be retired in favor of cleaner-burning hydrogen models. Demonstration hydrogen trucks are operational at the Port of Los Angeles, and 48 hydrogen buses are being used by local transportation agencies.

Hydrogen boosters note that the far more popular battery-powered cars are experiencing their own growing pains, as automakers and regulators confront supply-chain challenges and environmental questions complicating the push to rid the planet of climate-unfriendly internal combustion engines. The hydrogen cars can go 400 miles on a full tank, and they don’t require waiting around for a battery to charge.

ABOUT THIS SERIES

No state has had a bigger impact on the direction of the United States than California, a prolific incubator and exporter of outside-the-box policies and ideas. This occasional series examines what that has meant for the state and the country, and how far Washington is willing to go to spread California’s agenda as the state’s own struggles threaten its standing as the nation’s think tank.

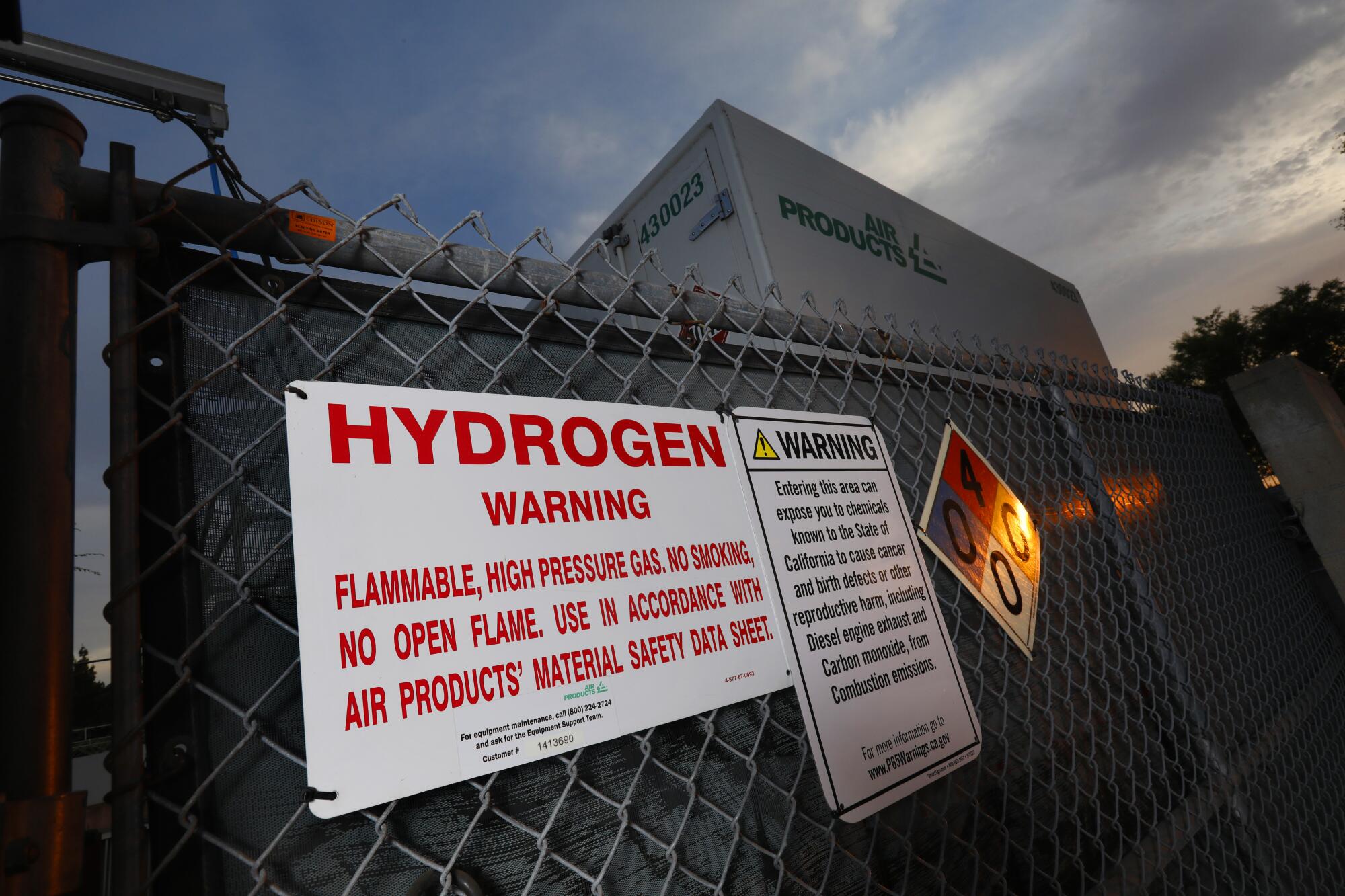

Yet nearly two decades into the hydrogen experiment, it remains a uniquely expensive gambit. The state has spent $125 million to make its struggling network of 50 public hydrogen fueling stations operational. That network is still so shaky — with stations frequently malfunctioning or out of fuel — that Toyota provides free towing and car rental service to drivers who purchase a Mirai, as getting stranded is a constant risk.

“It was a regular sight to see a car coming in on a flatbed when I went to get fuel,” said Scott Lerner, a writing instructor at UC Irvine who leased a Mirai until the hardship of hydrogen motoring got to be too much. “We would often have these commiserating circles at the station, where people would share horror stories.”

The state is undeterred. At the end of last year, as Lerner was retiring his Mirai, the California Energy Commission was greenlighting an additional $169 million for fueling stations. The panel hopes to help open 111 more stations by 2027, plus 13 that can also service trucks and buses.

That is a subsidy from the state of more than $1 million per station, mostly for a fleet of about 9,000 private vehicles. They are mainly Mirais, but there are also a smattering of Hyundai and Honda hydrogen cars on the freeways. In the latest unencouraging sign for Hydrogen Highway evangelists, Honda this month announced that it will soon stop selling the Clarity, the one hydrogen model it has available.

The news was met with relief by some.

“Failure is never something to celebrate, but nor is wasting money on dead end transport solutions,” Michael Liebreich, a clean-energy analyst, wrote on Twitter.

This is not the way things usually go for California, which is accustomed to having its pioneering policies enthusiastically embraced by other Democratic-led states. In this case, however, many California transportation visionaries are ready to move on and focus all efforts on battery-powered zero-emission passenger cars, which accounted for 1.1 million of the more than 14 million cars sold nationwide last year. But the big business interests invested in hydrogen are harnessing their influence to preserve the status quo.

Among those lobbying Gov. Gavin Newsom to vastly expand California’s investment in the Hydrogen Highway are Chevron, Shell, Toyota, Hyundai and BMW. Within their ranks is Henry Perea, the former assemblyman who wrote the transportation bill mandating funding for hydrogen stations. He is now a lobbyist for Chevron.

The firms assert that the fuel is green, yet the “100% renewable” hydrogen sold at California fueling stations is made with natural gas. It gets branded as renewable through a scheme in which hydrogen companies pay to trap greenhouse-gas-intensive methane from landfills and farming operations elsewhere in the country. The companies don’t use the resulting biogas, which gets pumped into natural gas pipelines, except to generate carbon credits they rely on to claim their fuel is green.

“You are still avoiding those greenhouse gases and getting all the benefits from an environmental point of view,” said Shane Stephens, founder of the hydrogen fuel company True Zero.

Some environmental groups, including the Sierra Club, see it differently.

“It is not renewable,” said Sasan Saadat, an analyst at Earthjustice. “What they are doing does not make sense.” There is so much natural gas involved in the fuel production process, he said, that calling it sustainable is indefensible. While hydrogen could ultimately prove the most effective method to cut emissions from trucks and planes, the Hydrogen Highway concept for cars just isn’t penciling out, Saadat said.

The Energy Commission aspires toward truly renewable fuel for hydrogen cars, a goal achieved by the engineers who run the fueling station at Cal State Los Angeles. The caveat is that this costs a fortune — double or triple the price of making other hydrogen fuel, which is already so costly that Toyota provides $15,000 fuel cards to lure drivers into Mirais.

“It’s still a long ways off,” said Michael Dray, who runs the Cal State station. He mocks assurances from hydrogen producers and the state that all the fuel on the Hydrogen Highway will be green within the decade.

“Think very carefully before investing in this technology,” said Dray, adding that the “party line” is deceptively upbeat.

“Do not be deceived by these people,” he said. “Big corporations are having a hard time with this. Major oil companies are having trouble making the stations run. The auto manufacturers are having trouble with the cars.”

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Toyota officials take exception. They argue that the ridicule of hydrogen car technology — Elon Musk calls the fuel cells “fool sells” — resembles what they encountered when the wildly successful and widely copied Prius hybrid debuted.

“We think in terms of decades, not one cycle,” said Craig Scott, a manager at the company’s Electrified Vehicles & Technology Office.

In Europe, where some 2,000 hydrogen cars and vans are scattered across the continent, both BMW and Jaguar Land Rover are mulling over the launch of a hydrogen model.

In the U.S., there are plenty of Mirai drivers who share Toyota’s outlook. These true believers can be found on Mirai owner Facebook pages, warring with drivers posting rants about getting stranded, waiting intolerably long for fuel and struggling to get the pump nozzle unfrozen from their fuel tank. It is a volatile corner of the World Wide Web.

“The car was almost free,” said Feridoon Aslani, 61, an actor and writer. “I am happy with it.”

He praised his 2017 Mirai even as he waited two hours for fuel in Diamond Bar. The station was overwhelmed by desperate Mirai drivers seeking a fill after one of the scant fueling stations in the nearby Inland Empire went down. One car arrived by flatbed.

But Aslani, who lives in Santa Monica, said the $15,000 in free fuel Toyota is giving hydrogen pioneers was too good a deal to pass up, and the vehicles work fine for Angelenos on the Westside, where there is a critical mass of fueling stations.

Eunjin Hana Joo’s enthusiasm for the Mirai she rents to the hydrogen-curious in Los Angeles was tempered after she took two journalist clients to fill the tank at Dray’s station. It was disappointing, the 30-year-old artist said, to learn that most of the fuel she had been using was made with natural gas. “The point is to reduce our carbon footprint,” she said. “Why are we creating it?”

Joo, who had been in a rush to make her next appointment, found herself stuck an extra 20 minutes at the station, because fuel pumps had shut down in the heat, another recurring challenge.

Maribel Munoz knows all about that. She pulled into the Diamond Bar station during the June heat wave to find that the app had deceived her again. The station was down — too hot. She had to wait three hours until it was cool enough to pump fuel — and the pump stopped dispensing at half a tank.

Munoz vented on Facebook as she waited. The next day, she drove to the Toyota dealer to demand that it buy back the vehicle.

“There were so many problems that kept me from using the car,” Munoz said, “that I called it my lawn ornament.”

Toward a more sustainable California

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter exploring climate change, energy and the environment, and become part of the conversation — and the solution.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.