Whither Trumpism? With the president’s reelection uncertain, Republicans battle over their future

- Share via

WASHINGTON — President Trump has transformed the Republican Party over the last four years, but now, with his reelection in doubt, Republicans have begun to sharply divide on whether those changes will — or should — outlast his presidency.

Old Guard Republicans acknowledge that there is no going back to the pre-Trump status quo, but see a political opening to steer the party away from Trumpism. At the same time, Trump’s allies have started to jockey for primacy in a potential post-Trump party.

Those tensions have already begun to have an impact on legislation, leadership power struggles and campaign strategy in Congress and across the country.

In two Senate GOP primaries this week, Trump allies have been facing stiff challenges — from the right in Tennessee and the center in Kansas.

Divisions have surfaced among congressional Republicans over how to handle the next installment of COVID-19 relief funding, with many of the splits directly related to jockeying over the party’s future.

And after years of nearly unbroken fealty to the president, Republicans have increasingly defied Trump’s wishes on issues, including his proposal for a payroll tax cut, funding for a new FBI building — and most resoundingly, his suggestion of a possible delay of election day, which Republican leaders in the House and Senate rebuffed.

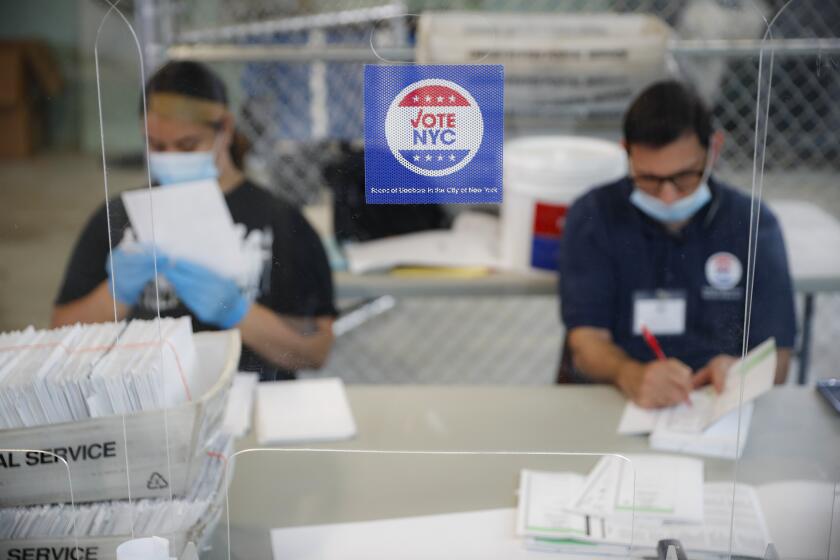

The pandemic has pushed elections system to the brink, with officials in some states fearing a meltdown this fall. Lack of money is a major problem.

“This is a party that knows it’s going to get beaten and get beaten badly,” said Peter Wehner, a Trump critic and former White House advisor to President George W. Bush. “Intra-party turmoil, attacks on each other, the language gets super-heated.”

Still, Trump loyalists remain on guard against apostasy. Wyoming Rep. Liz Cheney, a rising GOP star critical of the president on some issues, recently came under fire from a back-bencher who called for her to be booted from the House leadership.

Anti-Trump Republicans are fighting back in the 2020 campaign by forming political groups dedicated to keeping Trump from being reelected.

But they face formidable hurdles in rolling back the broader changes Trump has wrought because the voting base of the GOP has been transformed. Country-club Republicanism has been routed, eclipsed by an influx of blue-collar populists who care more about cutting immigration than traditional GOP issues such as deregulation or free trade. At the same time, Trump has alienated many suburban voters who once were mainstays of the party.

That’s why many Republicans — both Trump supporters and his opponents — believe his influence will persist even if his presidency does not.

“Donald Trump will have as big an impact on the profile of the Republican Party as Ronald Reagan did,” said Kevin Madden, a veteran of several GOP presidential campaigns including Mitt Romney’s in 2012, who has since left the party.

“This party and how it wages battles on issues, with the media and with Democrats will be led by him for the foreseeable future.”

The biggest fight within the party may be over who can claim to be Trump’s heir.

In Central Valley and other conservative parts of California, small but significant numbers of Republican voters have turned against Trump.

“Whether he wins or loses in 2020, you’re going to see a contest between people trying to carry the mantle of Trumpism,” said Andy Surabian, a former Trump aide who now advises the president’s son Donald Trump Jr.

“He is going to be the most influential Republican figure, whether he wins or loses,” said Surabian. “You’re not going to see a pro-amnesty, pro-foreign-intervention, pro-unrestricted trade Republican get the nomination for president in 2024.”

The battle over the post-Trump shape of the party will be waged in part on Capitol Hill, where Trump has remade the GOP by sweeping in a new generation of more populist, nationalist Republican legislators, while driving out more traditional Republicans and those who crossed him. One-third of the House’s 198 Republican members were elected since 2016, most on Trump’s agenda and coattails, and many will stay in Washington long after Trump leaves.

Senate primaries continue to be feuds over which Republican will be the president’s most loyal ally, and Trump has often bragged about his ability to carry GOP candidates to primary victories. But the campaigns for this week’s primaries in Tennessee and Kansas showed signs of Trump’s weakening grip.

In Tennessee, where Republicans on Thursday are choosing a nominee to succeed GOP Sen. Lamar Alexander, who is retiring, the candidate endorsed by Trump is not a shoo-in. Trump’s former ambassador to Japan, Bill Hagerty, is meeting a spirited challenge from the right from Manny Sethi, a surgeon who has been endorsed by conservative stalwarts like Sens. Ted Cruz of Texas and Rand Paul of Kentucky and Jim DeMint, a former senator and head of the conservative Heritage Foundation.

In Kansas, longtime Trump ally Kris Kobach — a polarizing conservative who lost his 2018 gubernatorial bid — lost again in Tuesday’s GOP primary for the seat now held by retiring GOP Sen. Pat Roberts.

The GOP establishment — including the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Senate Leadership Fund, which is allied with Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Kentucky — backed a rival they believe is less divisive, Rep. Roger Marshall, because they feared Kobach would lose the Senate general election.

Trump did not endorse either, despite pressure from GOP leaders for him to back Marshall.

The party’s split from its Old Guard past is illustrated in both primaries, as Republicans seized a new weapon for demonizing their rivals: Linking them to Romney, the only Republican senator to vote against Trump in his impeachment trial.

Republican anti-Trump groups aim to convince just enough GOP voters that it’s OK to support a Democrat to oust this president.

In Kansas, the Club for Growth, a conservative political group, has aired ads calling Marshall a friend of “never-Trump politicians like Mitt Romney.” In Tennessee, Hagerty has had to defend his service as Romney’s finance chair in the 2012 campaign.

On Capitol Hill, intraparty warfare broke out recently when Cheney, No. 3 leader of the House GOP, came under attack from members of the conservative House Freedom Caucus for, among other things, her criticism of Trump’s foreign policy and his handling of the coronavirus crisis.

Cheney, daughter of former Vice President Dick Cheney, poked Trump for his refusal to wear a mask to prevent the disease’s spread by tweeting a photo of her father wearing one, with the hashtag #realmenwearmasks.

Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida, a Trump ally, tweeted after a closed-door confrontation, “Liz Cheney has worked behind the scenes (and now in public) against @realDonaldTrump and his agenda. House Republicans deserve better as our Conference Chair. Liz Cheney should step down or be removed #MAGA.”

Cheney has supported Trump on most issues, and the call to oust her fizzled.

Michael Steel, a former aide to House Speaker John Boehner, said Cheney’s attackers “kicked off a new front in the fight to define the future of the Republican Party in the post-Trump era, an era they clearly worry will begin quite soon. “

Writing for the Dispatch, a conservative website, Steel called Cheney a “‘back to the future’ option for the future of the party — advocating a return to fiscal responsibility, an assertive foreign policy, and competence. And there are many who agree with her.”

In the Senate, the divisions among Republicans have worsened the stalemate over the next package of economic relief for the damage caused by COVID-19.

One hallmark of Trumpism is the president’s lack of concern about the ballooning federal budget deficit. Republicans have mostly gone along, abandoning their past embrace — at least rhetorically — of fiscal conservatism.

Now, in a sign of Trump’s weakened position on the Hill, some Republicans with presidential ambitions like Sens. Josh Hawley of Missouri and Cruz have begun complaining about growing costs — despite the risk that a delayed or smaller relief package might pose to Republicans in tough reelection fights this year.

Trump has had little hand in shaping the package so far, leaving negotiations to his top aides. When he has weighed in, he has been slapped down by fellow Republicans, such as when he proposed a payroll tax cut and when his administration pushed unrelated funding for construction of an FBI headquarters in downtown Washington, D.C., across the street from the hotel Trump owns.

If Trump wins in 2020, he will have another four years to cement the changes he has wrought in the GOP. If he loses, Republicans’ reaction will hinge largely on how big and decisive his defeat is. Short of a landslide, however, it is unlikely that Trump’s influence on the party will vanish, Republicans on both sides say.

Tim Miller, an anti-Trump Republican who worked for Jeb Bush in the 2016 presidential election, said Trump is not likely to follow the lead of President George W. Bush, who retreated to private life and hobbies on his Texas ranch after leaving the White House.

“He’s going to be tweeting. He’ll have his own network,” Miller said. “He is not the type to go to Midland and paint.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox three times per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.